Well-intentioned regulations to protect Canada’s most productive farmland restrict large-scale solar photovoltaic (PV) development. The recent innovation of agrivoltaics, which is the co-development of land for both PV and agriculture, makes these regulations obsolete. Burgeoning agrivoltaics research has shown agricultural benefits, including increased yield for a wide range of crops, plant protection from excess solar energy and hail, and improved water conservation, while maintaining agricultural employment and local food supplies. In addition, the renewable electricity generation decreases greenhouse gas emissions while increasing farm revenue. The background on Ontario land-use Policy and policy recommendations about agrivoltaics are discussed.

- agriculture

- Ontario

- energy policy

1. Background on Ontario Land-Use Policy

1.1. Governance

1.2. Agricultural Heritage

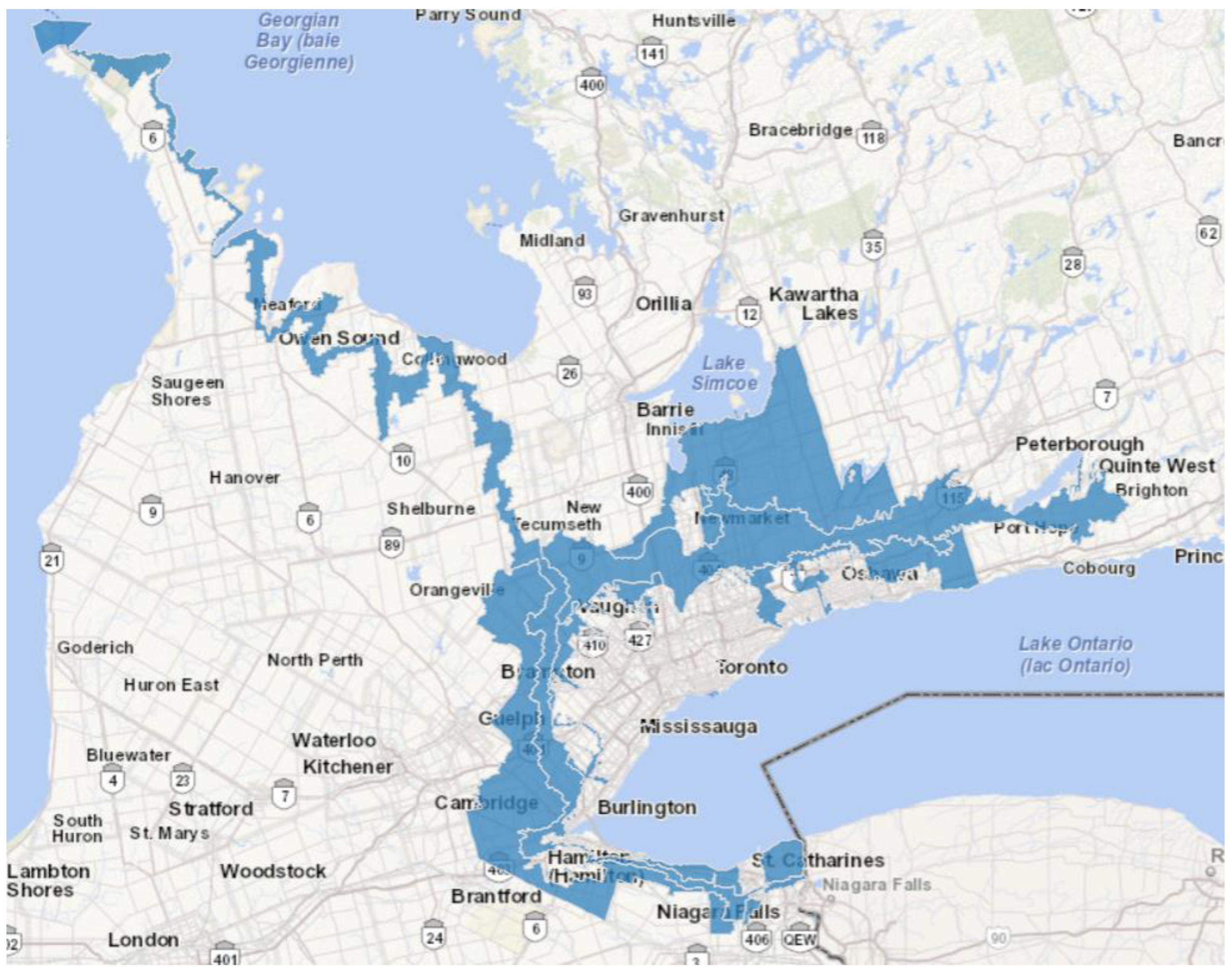

1.3. Land Use Policy in the Greenbelt

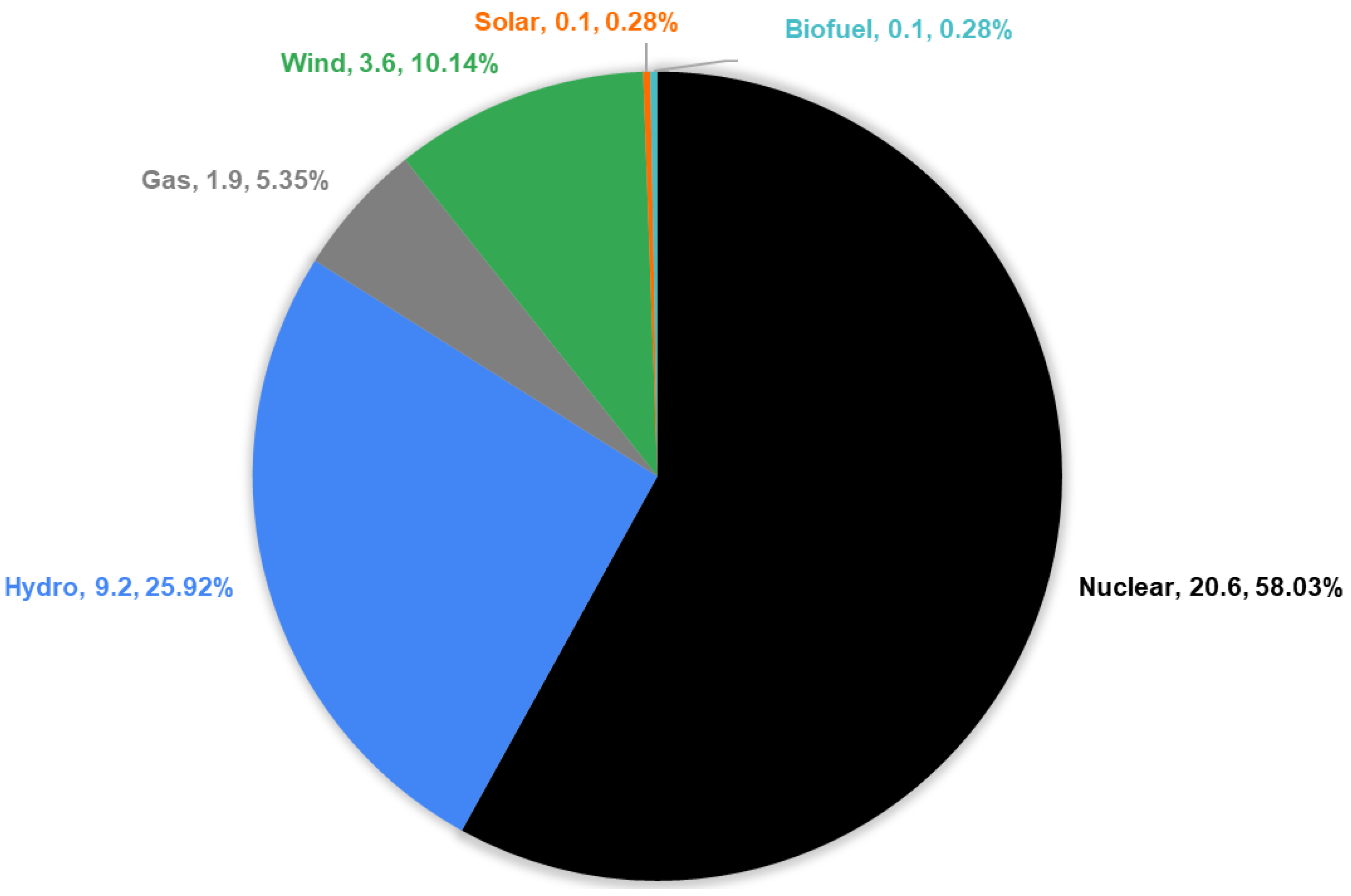

1.4. Renewable Energy Policy

1.5. The Intersection of Agriculture and Solar Energy in Ontario

-

Is related to, and can coexist with, agricultural operation

-

Must not impair, inconvenience, or undermine surrounding agricultural operation

-

Be located on a farm actively in production and be limited in an area based on a lot coverage ratio basis (emphasis added)

-

Meet all applicable provincial air emission, noise, water, and wastewater standards and receive all relevant environmental approvals

2. Policy Recommendations

2.1. Support-Applied Agrivoltaic Research in Ontario

2.2. Increase Public Awareness of Agrivoltaics in Ontario

To overcome these challenges related to the vast quantity of research needed in agrivoltaics, a parametric open-source cold-frame agrivoltaic system (POSCAS) was proposed to make low-cost agrivoltaic testing systems work in one single-module mini greenhouse at a time [115][36]. These devices could be used at a research station to test many variables at once. More importantly, these devices could also be used to foster public awareness of agrivoltaics using the approach of citizen science [116,117][37][38]. By enabling citizens to investigate the large number of permutations of PV designs and crops, two problems will be solved simultaneously. Such an enterprise could first, for example, target the help of master gardeners to quickly screen local produce for benefits for agrivoltaics by providing them with a free POSCAS and open-source, collaborative, well-structured, online research reporting. This would minimize R&D costs while also educating the wider population about the benefits of agrivoltaics. Most North Americans are simply unaware of agrivoltaics, but when exposed to the idea they are in support of it [118][39]. Citizen science, similar to that described above, may help in part with public awareness, but broad, openly-accessible demonstrations are needed to verify the viability of the agrivoltaic approach in Ontario and to inform policymakers as well as build public trust. After preliminary experimental Ontario-based agrivoltaic studies indicate promise, open pilot studies should be conducted to allow farmers and citizens free access to the results. Opening rural lands to agrivoltaic R&D and demonstration can also prevent other types of proposed development on prime agricultural lands, while ramping up education on agrivoltaics in the province.2.3. Streamlined Agrivoltaic System Deployment and Regulation

Given the modest agrivoltaic presence in Canada currently, in addition to more R&D and public education, there exists a need for an explicit definition and classification of agrivoltaic systems for regulation purposes. Agrivoltaics transcend traditional photovoltaic development by allowing continued use of the farmland beneath the array and is therefore uniquely positioned to enable the prosperity of agricultural producers and the diversification of their income, while stimulating rural economic growth through the generation of low-carbon electricity from sunlight. A proper definition is needed to acknowledge that agrivoltaics will not disrupt the geographic continuity of the agricultural land base. To prevent abuse of agrivoltaic-friendly regulations, it may be useful to divide agrivoltaics up into tiers, as is shown in Table 1. Tier 1 agrivoltaic solutions would be preferred and incentivized over Tier 2, etc. Such a tiered system would, for example, prevent a solar developer from simply seeding a conventional PV farm with wildflowers to acquire access to prime agricultural land. Ontario can look to other jurisdictions, such as Japan, the U.S. and Europe, for examples of effective agrivoltaic policy. In Japan, agrivoltaic development exploded after the introduction of feed-in tariff (FIT) in 2012 [119][40]. Tajima and Iida found that the FIT was significantly more effective than a renewable portfolio standard (RPS) system previously used in Japan and that agrivoltaics is expected to play a major role in revitalizing Japanese agriculture, including reclamation of abandoned farmland [119][40]. Canada thus has the opportunity to reintroduce a FIT targeted specifically on agrivoltaics, and Ontario already has experience in this domain with the Green Energy Act. Perhaps even more targeted, the Massachusetts Department of Energy Resources established the Solar Massachusetts Renewable Target (SMART) program that regulates and provides incentives for PV, and agrivoltaics in particular [120,121,122][41][42][43]. The economics of PV are profitable in Ontario, but could be strengthened, and a program could help overcome other barriers, including access to low-interest capital and streamlining the process with utilities and other sources of bureaucracy. In Europe, a standard has been developed as a test method for agrivoltaic systems that provides a uniform way to report agrivoltaic measurement figures for legislative and funding bodies and the approval authorities, as well as for the post-testing and certification of agrivoltaic systems by experts and certification organizations [123][44]. Canada, in general, and Ontario specifically, could build upon and improve upon these standards to ensure they remain open access and thus freely available to all Ontario’s farmers.| Tier/Allowed Land Use | Agrivoltaic Type | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Prime agriculture | Crop | See Section 5.1 for crops investigated to date |

| 2. Pasture | Grazing | Sheep [51,124][45][46], and rabbits [73][47] |

| 3. Marginal | Apiculture (beekeeping) |

Honey production [125][48] |

| 4. Non-restricted | Insect Habitat | Pollinators, e.g., butterflies, that provide secondary services |

References

- City of Toronto. Powers of Canadian Cities—The Legal Framework. 2001. Available online: https://www.toronto.ca/ext/digital_comm/inquiry/inquiry_site/cd/gg/add_pdf/77/Governance/Electronic_Documents/Other_CDN_Jurisdictions/Powers_of_Canadian_Cities.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2021).

- Greenbelt Designation. Available online: https://geohub.lio.gov.on.ca/datasets/greenbelt-designation/explore (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Government of Ontario. Provincial Policy Statement, 2020. 2020. Available online: https://files.ontario.ca/mmah-provincial-policy-statement-2020-accessible-final-en-2020-02-14.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2021).

- Government of Ontario. A Place to Grow: Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe. 2020. Available online: https://files.ontario.ca/mmah-place-to-grow-office-consolidation-en-2020-08-28.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2021).

- Government of Ontario. Greenbelt Plan. 2017. Available online: https://files.ontario.ca/greenbelt-plan-2017-en.pdf (accessed on 6 November 2021).

- Government of Canada, CER. Canada’s Adoption of Renewable Power Sources—Energy Market Analysis. Canada Energy Regulator. 2020. Available online: https://www.cer-rec.gc.ca/en/data-analysis/energy-commodities/electricity/report/2017-canadian-adoption-renewable-power/canadas-adoption-renewable-power-sources-energy-market-analysis-solar.html (accessed on 6 November 2021).

- Ontario Energy Quarterly: Electricity in Q4 2020. Available online: http://www.ontario.ca/page/ontario-energy-quarterly-electricity-q4-2020 (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Geerts, H.; Robertson, A.; Ontario; Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs. Guidelines on Permitted Uses in Ontario’s Prime Agricultural Areas; Ontario Ministry of Agriculture: Guelph, ON, Canada, 2016; ISBN 978-1-4606-8529-7.

- Green Energy and Green Economy Act. Available online: https://www.ontario.ca/laws/view (accessed on 2 March 2022).

- Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs. Area, Production and Farm Value of Specified Commercial Vegetable Crops, Ontario. Available online: http://www.omafra.gov.on.ca/english/stats/hort/veg_all15-16.htm (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs. Estimated Area, Yield, Production and Farm Value of Specified Field Crops, Ontario (Imperial and Metric Units). Available online: http://www.omafra.gov.on.ca/english/stats/crops/estimate_new.htm (accessed on 21 December 2021).

- Ravi, S.; Macknick, J.; Lobell, D.; Field, C.; Ganesan, K.; Jain, R.; Elchinger, M.; Stoltenberg, B. Colocation Opportunities for Large Solar Infrastructures and Agriculture in Drylands. Appl. Energy 2016, 165, 383–392.

- Pringle, A.M.; Handler, R.M.; Pearce, J.M. Aquavoltaics: Synergies for dual use of water area for solar photovoltaic electricity generation and aquaculture. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 80, 572–584.

- Thompson, E.P.; Bombelli, E.L.; Shubham, S.; Watson, H.; Everard, A.; D’Ardes, V.; Schievano, A.; Bocchi, S.; Zand, N.; Howe, C.J.; et al. Tinted Semi-Transparent Solar Panels Allow Concurrent Production of Crops and Electricity on the Same Cropland. Adv. Energy Mater. 2020, 10, 2001189.

- Weselek, A.; Bauerle, A.; Zikeli, S.; Lewandowski, I.; Högy, P. Effects on Crop Development, Yields and Chemical Composition of Celeriac (Apium graveolens L. Var. Rapaceum) Cultivated Underneath an Agrivoltaic System. Agronomy 2021, 11, 733.

- Barron-Gafford, G.A.; Pavao-Zuckerman, M.A.; Minor, R.L.; Sutter, L.F.; Barnett-Moreno, I.; Blackett, D.T.; Thompson, M.; Dimond, K.; Gerlak, A.K.; Nabhan, G.P.; et al. Agrivoltaics Provide Mutual Benefits across the Food–Energy–Water Nexus in Drylands. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 848–855.

- Sekiyama, T.; Nagashima, A. Solar Sharing for Both Food and Clean Energy Production: Performance of Agrivoltaic Systems for Corn, a Typical Shade-Intolerant Crop. Environments 2019, 6, 65.

- Amaducci, S.; Yin, X.; Colauzzi, M. Agrivoltaic systems to optimize land use for electric energy production. Appl. Energy 2018, 220, 545–561.

- Malu, P.R.; Sharma, U.S.; Pearce, J.M. Agrivoltaic potential on grape farms in India. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2017, 23, 104–110.

- Hudelson, T.; Lieth, J.H. Crop Production in Partial Shade of Solar Photovoltaic Panels on Trackers. AIP Conf. Proc. 2021, 2361, 080001.

- Marrou, H.; Wery, J.; Dufour, L.; Dupraz, C. Productivity and radiation use efficiency of lettuces grown in the partial shade of photovoltaic panels. Eur. J. Agron. 2013, 44, 54–66.

- Elamri, Y.; Cheviron, B.; Lopez, J.-M.; Dejean, C.; Belaud, G. Water Budget and Crop Modelling for Agrivoltaic Systems: Application to Irrigated Lettuces. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 208, 440–453.

- Adeh, E.H.; Selker, J.S.; Higgins, C.W. Remarkable Agrivoltaic Influence on Soil Moisture, Micrometeorology and Water-Use Efficiency. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203256.

- Trommsdorff, M.; Kang, J.; Reise, C.; Schindele, S.; Bopp, G.; Ehmann, A.; Weselek, A.; Högy, P.; Obergfell, T. Combining Food and Energy Production: Design of an Agrivoltaic System Applied in Arable and Vegetable Farming in Germany. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 140, 110694.

- Dupraz, C.; Marrou, H.; Talbot, G.; Dufour, L.; Nogier, A.; Ferard, Y. Combining Solar Photovoltaic Panels and Food Crops for Optimising Land Use: Towards New Agrivoltaic Schemes. Renew. Energy 2011, 36, 2725–2732.

- Marrou, H.; Guilioni, L.; Dufour, L.; Dupraz, C.; Wéry, J. Microclimate under agrivoltaic systems: Is crop growth rate affected in the partial shade of solar panels? Agric. For. Meteorol. 2013, 177, 117–132.

- Riaz, M.H.; Imran, H.; Alam, H.; Alam, M.A.; Butt, N.Z. Crop-Specific Optimization of Bifacial PV Arrays for Agrivoltaic Food-Energy Production: The Light-Productivity-Factor Approach. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.00560.

- PFAF. Edible Uses. Available online: https://pfaf.org/user/edibleuses.aspx (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Agricultural Adaptation Council. “Waste” Light Can Lower Greenhouse Production Costs. In Greenhouse Canada; Agricultural Adaptation Council: Guelph, ON, Canada, 30 December 2019.

- Growing Trial for Greenhouse Solar Panels—Research & Innovation|Niagara College. Research & Innovation 2019. Available online: https://www.ncinnovation.ca/blog/research-innovation/growing-trial-for-greenhouse-solar-panels (accessed on 25 October 2021).

- Chiu, G. Dual Use for Solar Modules. Greenhouse Canada 2019. Available online: https://www.greenhousecanada.com/technology-issues-dual-use-for-solar-modules-32902/ (accessed on 25 October 2021).

- El-Bashir, S.M.; Al-Harbi, F.F.; Elburaih, H.; Al-Faifi, F.; Yahia, I.S. Red Photoluminescent PMMA Nanohybrid Films for Modifying the Spectral Distribution of Solar Radiation inside Greenhouses. Renew. Energy 2016, 85, 928–938.

- Parrish, C.H.; Hebert, D.; Jackson, A.; Ramasamy, K.; McDaniel, H.; Giacomelli, G.A.; Bergren, M.R. Optimizing Spectral Quality with Quantum Dots to Enhance Crop Yield in Controlled Environments. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 124.

- UbiGro A Layer of Light. Available online: https://ubigro.com/case-studies (accessed on 22 September 2021).

- Weaver, J.F. All I Want for Christmas Is a Solar-Powered Greenhouse. Available online: https://pv-magazine-usa.com/2021/12/24/all-i-want-for-christmas-is-a-solar-powered-greenhouse/ (accessed on 26 December 2021).

- Pearce, J.M. Parametric Open Source Cold-Frame Agrivoltaic Systems. Inventions 2021, 6, 71.

- Cohn, J.P. Citizen Science: Can Volunteers Do Real Research? BioScience 2008, 58, 192–197.

- Bonney, R.; Cooper, C.B.; Dickinson, J.; Kelling, S.; Phillips, T.; Rosenberg, K.V.; Shirk, J. Citizen Science: A Developing Tool for Expanding Science Knowledge and Scientific Literacy. BioScience 2009, 59, 977–984.

- Pascaris, A.S.; Schelly, C.; Rouleau, M.; Pearce, J.M. Do Agrivoltaics Improve Public Support for Solar Photovoltaic Development? Survey Says: Yes! 2021. Available online: https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/efasx/ (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Tajima, M.; Iida, T. Evolution of Agrivoltaic Farms in Japan. AIP Conf. Proc. 2021, 2361, 030002.

- Ag. U. Mass. Dual-Use: Agriculture and Solar Photovoltaics. Available online: https://ag.umass.edu/clean-energy/fact-sheets/dual-use-agriculture-solar-photovoltaics (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs, Department of Energy Resources, Department of Agricultural Resources, Solar Massachusetts Renewable Target Program, (225 CMR 20.00), Guideline, Guideline Regarding the Definition of Agricultural Solar Tariff Generation Units, Effective Date: April 26, 2018. Available online: https://www.mass.gov/doc/agricultural-solar-tariff-generation-units-guideline-final/download (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- Levey, B.; Detterman, B.; Jacobs, H. Massachusetts SMART Program Regulations: More Solar Capacity, Less Land Area. Available online: https://www.bdlaw.com/publications/massachusetts-smart-program-regulations-more-solar-capacity-less-land-area/ (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- DIN SPEC 91434:2021-05; Agri-Photovoltaik-Anlagen_-Anforderungen an Die Landwirtschaftliche Hauptnutzung. Beuth Verlag GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2021.

- Mow, B. Solar Sheep and Voltaic Veggies: Uniting Solar Power and Agriculture|State, Local, and Tribal Governments|NREL , 2018. Available online: https://www.nrel.gov/state-local-tribal/blog/posts/solar-sheep-and-voltaic-veggies-uniting-solar-power-and-agriculture.html (accessed on 2 July 2020).

- Ouzts, E. Farmers, Experts: Solar and Agriculture ‘Complementary, Not Competing’ in North Carolina. Available online: http://energynews.us/2017/08/28/farmers-experts-solar-and-agriculture-complementary-not-competing-in-north-carolina/ (accessed on 22 December 2021).

- Lytle, W.; Meyer, T.K.; Tanikella, N.G.; Burnham, L.; Engel, J.; Schelly, C.; Pearce, J.M. Conceptual Design and Rationale for a New Agrivoltaics Concept: Pasture-Raised Rabbits and Solar Farming. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 282, 124476.

- Amelinckx, A. Solar Power and Honey Bees Make a Sweet Combo in Minnesota. Smithsonian Magazine. Available online: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/solar-power-and-honey-bees-180964743/ (accessed on 22 December 2021).