Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Rita Xu and Version 1 by Kang Nien How.

Atopic dermatitis, the most common form of eczema, is a chronic, relapsing inflammatory skin condition that occurs with dry skin, persistent itching, and scaly lesions. This debilitating condition significantly compromises the patient’s quality of life due to the intractable itching and other associated factors such as disfigurement, sleeping disturbances, and social stigmatization from the visible lesions. The treatment mainstay of atopic dermatitis involves applying topical glucocorticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors, combined with regular use of moisturizers.

- atopic eczema

- moisturizers

- emollients

1. Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease [1] that usually starts in early childhood. AD affects 15–20% of children worldwide and can extend well into adulthood at an incidence of 1–3% [2,3][2][3]. A wide variation of prevalence is reported, where AD is reported more frequently in developed nations with more than a 15% prevalence rate [3,4][3][4]. It can be diagnosed clinically following validated diagnostic criteria, such as the Hanifin and Rajka diagnostic criteria [5]. Eczematous rashes are itchy and can be acute, subacute, or chronic. Though able to affect any part of the body, eczematous rashes appear with age-related morphology and distribution. It is found to be associated with other atopic diseases. Children with atopic eczema are at risk of cutaneous infections. AD was found to be associated with poorer quality of life (QoL) [6]. The epidermal barrier plays a pivotal role in atopic eczema pathogenesis. The treatment of AD focuses on maximizing skin barrier repair and reducing inflammation. Topical corticosteroids (TCS) are the first-line anti-inflammatory treatment for AD. However, chronic usage of topical corticosteroids may further lead to skin barrier defects by inhibiting epidermal proliferation, differentiation, and lipid production [7].

Twice daily application of moisturizer improves skin hydration, reduces AD symptoms, flares, and severity, and reduces the amount of topical anti-inflammatory medication needed [8,9,10][8][9][10]. Conventional moisturizer consists of three main ingredients: emollients, humectants, and occlusive agents [9,11][9][11]. These ingredients reduce transepidermal water loss (TEWL) via various mechanisms. Emollients lubricate and soften the skin, while occlusive agents form a hydrophobic layer on the stratum corneum (SC) and prevent water evaporation. Meanwhile, humectants increase the amount of water retained by the SC through their hydrophilic nature [8,9,11][8][9][11]. In recent years, medical device emollient creams (MDEC) containing active ingredients have started to become the trend in the current cosmeceutical research, owing to their ability to alleviate cutaneous inflammation while repairing skin barriers [12,13,14][12][13][14]. Studies on various active ingredients with in vivo and in vitro efficacy have been published. Some are reported to be non-inferior to low potency corticosteroids [15].

2. Pathophysiology of AD

A fundamental argument on the etiology of AD is whether it is primarily induced by epidermal barrier dysfunction (outside–inside hypothesis) or primarily by an immune response to environmental triggers (inside–outside hypothesis) [16]. Nevertheless, the clinical manifestation of AD is believed to involve a multifactorial interplay among gene and epidermal barrier dysfunction, Th2 immune dysregulation, environmental triggers, and skin microbiome abnormalities [16,17,18][16][17][18]. Additionally, skin pH levels [19,20][19][20] and the deficiency of endogenous natural moisturizing factors (NMFs) [21,22][21][22] were also found to play a role.2.1. Gene Dysfunction and Epidermal Barrier Dysfunction

FLG gene mutation was found in 20–40% of patients with atopic dermatitis. It encodes the pre-protein profilaggrin, which will then be translated to filaggrin monomer. Filaggrin is required for keratinization, moisturization, and maintenance of the stratum corneum homeostasis [23]. The lack of filaggrin will lead to disruption of barrier function. FLG gene expression may be further downregulated when it is cross-linked with the T-helper type 2 cells (Th2) derived cascades. SC and tight junctions play the most critical roles in the epidermal barrier. SC is made up of corneocytes intermixed in a matrix of intercellular lipids (ceramides, cholesterol, and fatty acids) [3,23][3][23]. Environmental triggers, including irritants, pruritogens, hot and dry climate, and ultraviolet radiation, can disrupt the epidermal barrier leading to higher skin pH levels, increased TEWL, altered lipid composition, reduced level of ceramides, and higher serine protease activity [13,24][13][24]. Ceramide plays an essential structural role in forming the permeability barrier that functions as a water reservoir, holding the water molecules in the multilamellar structures. The prolonged compromised global lipid composition of SC in AD sufferers and the further deficiency in ceramide fraction eventually lead to barrier dysfunction, decreased SC hydration, S. aureus colonization, as well as allergen penetration. Hence, the mitigation of the barrier abnormality in AD requires topical aid that adequately delivers the key lipids that mediate barrier function, which is ideally provided in a ceramide-dominant proportion [25,26,27][25][26][27].2.2. Th2 Mediated Immune Dysregulation and Neuroimmune Interactions

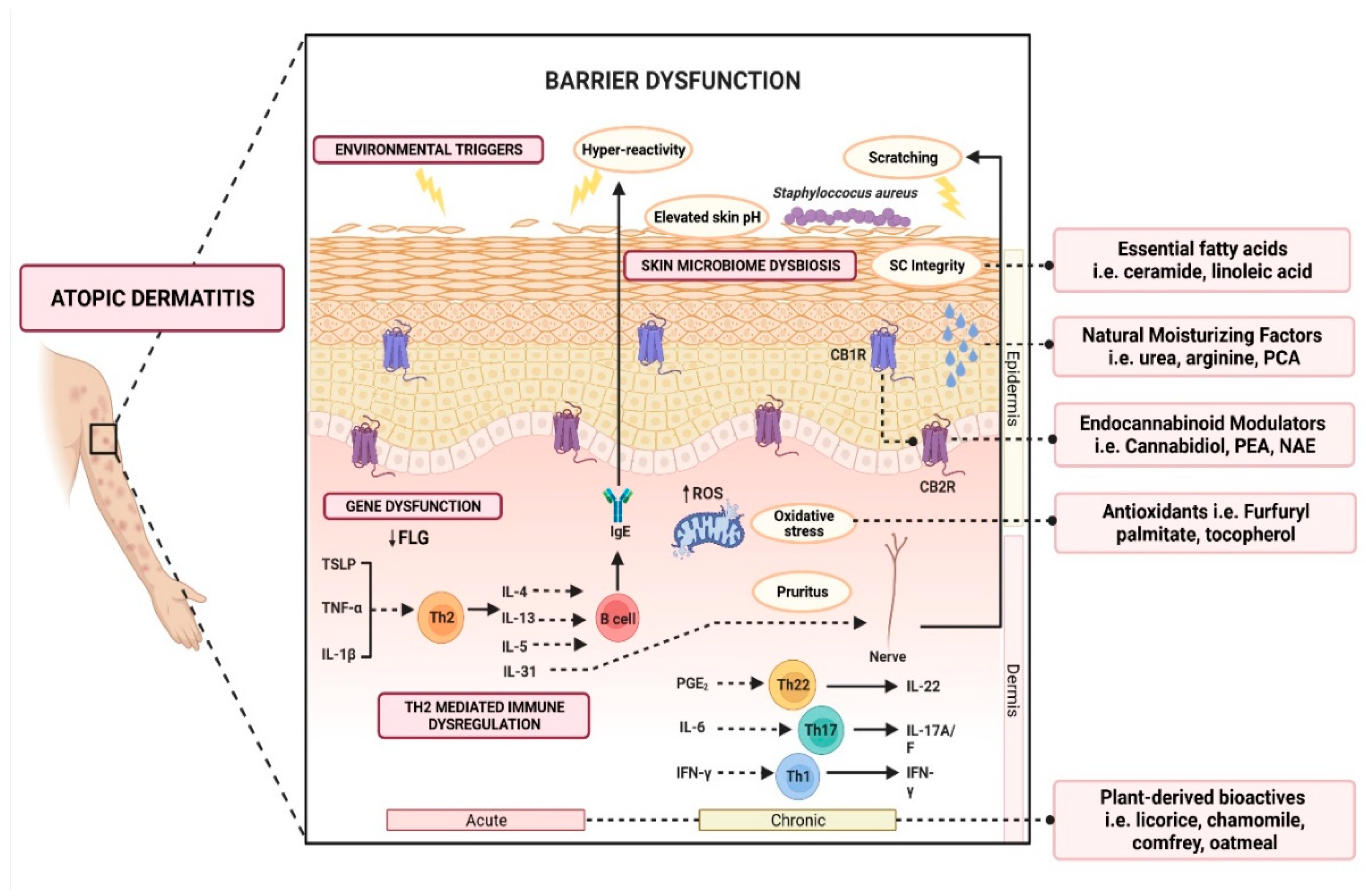

The Th2-mediated immune response is currently at the center of AD pathogenesis. The exposure of irritants and pruritogens to the disrupted epidermal barrier initiates an immunological cascade that stimulates Th2 pro-inflammatory cytokine production, such as interleukin-4 (IL-4), IL-5, and IL-13 [16,23][16][23]. Subsequently, IL-4 and IL-13 stimulate the production of IL-31, which results in pruritus, triggering excessive scratching and further aggravation of the inflammatory response (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of various active ingredients and the targeted mechanisms in alleviating atopic dermatitis.

2.3. Skin Microbiome Dysbiosis

The skin microbiome plays a pivotal role in maintaining the homeostasis of the skin, and colonization of Staphylococcus aureus strains in AD is thought to be associated with the clinical manifestation and pathogenesis of flares. S. aureus colonization was observed in up to 90% of lesional skin and 40% of non-lesional skin as opposed to being almost absent in healthy skin [28,29,30][28][29][30]. The dysbiosis contributes to the elevated pH levels that are observed throughout atopic dermatitis flares [31,32][31][32]. Furthermore, S. aureus colonies were found to secrete a group of virulence factors, such as superantigens (Sag), α-toxin, δ-toxin, protein A, and phenol-soluble modulins (PSM), that may exacerbate keratinocyte inflammation [28[28][29][30],29,30], release cytosolic granules (such as histamine, IL-3, and IL-13), aid in biofilm development and promote Staphylococcal colonization [30].2.4. Other Factors Affecting Barrier Function

2.4.1. Acid Mantle in Epidermal Barrier Function

Skin pH is a vital component in maintaining the normal functions of the skin [33,34][33][34]. The film of the outermost layer of the skin, known as the acid mantle, bears a pH range of 4.0–6.0, depending on body parts [34]. Neonatal skin pH is near-neutral, where it requires several weeks of acidification processes to attain physiological skin surface pH range, making it vulnerable to external irritants during this period [35]. Dysregulation of this acidification process leads to shifts in skin pH to a mean of 6.25 in AD [33,36,37][33][36][37]. The disruption of the acidification mechanism alters phospholipid A2, β-glucocerebrosidase, serine proteases, kallikrein 5, and acid sphingomyelinase activities, which are important for the maintenance of the lipid structure in SC [34,35,38][34][35][38]. The alteration of skin pH will impair the antimicrobial defenses of the skin [34,35,38][34][35][38]. Endogenous factors (such as the FLG gene and its amino acid breakdown, such as histidine) and exogenous factors (such as acidic and alkaline substances) have been proposed to affect the acid mantle of the skin [35,38,39][35][38][39].2.4.2. Natural Moisturizing Factors

Natural moisturizing factors (NMFs) refer to endogenous, highly hygroscopic substances that play a pivotal role in the maintenance of SC hydration [40]. NMFs also contribute to the maintenance of functional hydrolytic enzymes involved in desquamation and aid in optimum SC barrier function [40]. Amino acids account for 40–50% of NMFs, followed by pyrrolidone carboxylic acid (PCA) (12%), lactic acid (12%), urea (7%), inorganic salts, sugar, glycerol, and a variety of ions [40,41][40][41]. These water-soluble substances are highly efficient humectants that comprise 20–30% of the dry weight of SC mass [41]. The deficiency or reduction in NMFs is associated with an increased risk of AD and various SC abnormalities that manifest as dry skin, scaling, flaking, and increased surface pH [21,22][21][22].3. Role of Moisturizers in the Treatment of AD

Multiple clinical guidelines recommend the use of moisturizers for the treatment of AD [42]. This helps in reducing the frequency of AD flares (3.74 times reduced risk) [42] and the total amount of steroid use (up to 15.30 g less within six weeks, p = 0.003) [42]. Although a large variety of moisturizers are available in the market, not all are beneficial. Some formulations may contain allergens (e.g., fragrance, benzyl alcohol, D-limonene, Lavandula angustifolia oil, and Melaleuca alternifolia oil), leading to contact dermatitis and worsening of the inflammation [43]. Carefully designed moisturizers should be hypoallergenic, pH-balanced, and contain humectants, emollients, and active ingredients that help to reduce inflammation [43,44,45][43][44][45]. Some medical device emollient creams (MDEC) are found to be suitable for alleviating AD symptoms [46,47][46][47]. MDECs are clinically designed to not only improve hydration but also repair and protect the skin’s barrier function. According to the European Commission, some MDECs are classified as class IIa medical devices due to their primary action relying on mechanical or physical means [48]. Several notable MDECs, such as Atopiclair® (Menarini, Italy), Dexyane MeD® (Ducray Laboratoires Dermatologiques, France), and VEL-091604 (BSI Beauty Science Intelligence, Germany) have shown comparable clinical efficacy with corticosteroids in alleviating symptoms of moderate to severe AD, which will be discussed in the next section. Over the last few years, emollients have been supplemented with different powerful bioactive ingredients to improve epidermal action. These additives are increasingly investigated as preventative and treatment aids for AD. Notably, these additives are categorized as compounds derived from plants, natural moisturizing factors, physiological lipids and ceramide, cannabinoid receptor modulators, and antioxidants (Figure 1). Herein, a summary of evidence-based cosmeceutical research on additives in emollients indicated for AD is presented.References

- Langan, S.M.; Irvine, A.D.; Weidinger, S. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet 2020, 396, 345–360.

- Avena-Woods, C. Overview of atopic dermatitis. Am. J. Manag. Care 2017, 23, S115–S123.

- Nutten, S. Atopic dermatitis: Global epidemiology and risk factors. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2015, 66, 8–16.

- Silverberg, J.I.; Barbarot, S.; Gadkari, A.; Simpson, E.L.; Weidinger, S.; Mina-Osorio, P.; Rossi, A.B.; Brignoli, L.; Saba, G.; Guillemin, I.; et al. Atopic dermatitis in the pediatric population: A cross-sectional, international epidemiologic study. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021, 126, 417–428.e412.

- Hanifin, J.M.; Rajka, G. Diagnostic features of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm. Venereol. 1980, 1980, 44–47.

- Patel, K.R.; Immaneni, S.; Singam, V.; Rastogi, S.; Silverberg, J.I. Association between atopic dermatitis, depression, and suicidal ideation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2019, 80, 402–410.

- Li, A.W.; Yin, E.S.; Antaya, R.J. Topical corticosteroid phobia in atopic dermatitis: A systematic review. JAMA Dermatol. 2017, 153, 1036–1042.

- Barrett, A.; Hahn-Pedersen, J.; Kragh, N.; Evans, E.; Gnanasakthy, A. Patient-Reported Outcome Measures in atopic dermatitis and chronic hand eczema in adults. Patient 2019, 12, 445–459.

- Sidbury, R.; Davis, D.M.; Cohen, D.E.; Cordoro, K.M.; Berger, T.G.; Bergman, J.N.; Chamlin, S.L.; Cooper, K.D.; Feldman, S.R.; Hanifin, J.M.; et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: Section 3. Management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2014, 71, 327–349.

- Williams, H.C.; Burney, P.G.; Pembroke, A.C.; Hay, R.J. The U.K. Working Party’s diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis. III. Independent hospital validation. Br. J. Dermatol. 1994, 131, 406–416.

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898.

- Elias, P.M.; Wakefield, J.S.; Man, M.Q. Moisturizers versus current and next-generation barrier repair therapy for the management of atopic dermatitis. Skin Pharmacol. Physiol. 2019, 32, 1–7.

- Luger, T.; Amagai, M.; Dreno, B.; Dagnelie, M.-A.; Liao, W.; Kabashima, K.; Schikowski, T.; Proksch, E.; Elias, P.M.; Simon, M.; et al. Atopic dermatitis: Role of the skin barrier, environment, microbiome, and therapeutic agents. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2021, 102, 142–157.

- Sörensen, A.; Landvall, P.; Lodén, M. Moisturizers as cosmetics, medicines, or medical device? The regulatory demands in the European Union. In Treatment of dry Skin Syndrome; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Volume 8, pp. 3–16.

- Wananukul, S.; Chatproedprai, S.; Chunharas, A.; Limpongsanuruk, W.; Singalavanija, S.; Nitiyarom, R.; Wisuthsarewong, W. Randomized, double-blind, split-side, comparison study of moisturizer containing licochalcone A and 1% hydrocortisone in the treatment of childhood atopic dermatitis. J. Med. Assoc. Thai. 2013, 96, 1135–1142.

- Nakahara, T.; Kido-Nakahara, M.; Tsuji, G.; Furue, M. Basics and recent advances in the pathophysiology of atopic dermatitis. J. Dermatol. 2021, 48, 130–139.

- Bønnelykke, K.; Sparks, R.; Waage, J.; Milner, J.D. Genetics of allergy and allergic sensitization: Common variants, rare mutations. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2015, 36, 115–126.

- Eyerich, K.; Novak, N. Immunology of atopic eczema: Overcoming the Th1/Th2 paradigm. Allergy 2013, 68, 974–982.

- Jang, H.; Matsuda, A.; Jung, K.; Karasawa, K.; Matsuda, K.; Oida, K.; Ishizaka, S.; Ahn, G.; Amagai, Y.; Moon, C.; et al. Skin pH Is the master switch of kallikrein 5-mediated skin barrier destruction in a murine atopic dermatitis model. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2016, 136, 127–135.

- Zhu, Y.; Underwood, J.; Macmillan, D.; Shariff, L.; O’Shaughnessy, R.; Harper, J.I.; Pickard, C.; Friedmann, P.S.; Healy, E.; Di, W.L. Persistent kallikrein 5 activation induces atopic dermatitis-like skin architecture independent of PAR2 activity. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 140, 1310–1322.e1315.

- Basu, M.N.; Mortz, C.G.; Jensen, T.K.; Barington, T.; Halken, S. Natural moisturizing factors in children with and without eczema: Associations with lifestyle and genetic factors. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2022, 36, 255–262.

- Nouwen, A.E.M.; Karadavut, D.; Pasmans, S.; Elbert, N.J.; Bos, L.D.N.; Nijsten, T.E.C.; Arends, N.J.T.; Pijnenburg, M.W.H.; Koljenović, S.; Puppels, G.J.; et al. Natural moisturizing factor as a clinical marker in atopic dermatitis. Allergy 2020, 75, 188–190.

- Yang, G.; Seok, J.K.; Kang, H.C.; Cho, Y.Y.; Lee, H.S.; Lee, J.Y. Skin barrier abnormalities and immune dysfunction in atopic dermatitis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2867.

- Kantor, R.; Silverberg, J.I. Environmental risk factors and their role in the management of atopic dermatitis. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 2017, 13, 15–26.

- Chamlin, S.L.; Kao, J.; Frieden, I.J.; Sheu, M.Y.; Fowler, A.J.; Fluhr, J.W.; Williams, M.L.; Elias, P.M. Ceramide-dominant barrier repair lipids alleviate childhood atopic dermatitis: Changes in barrier function provide a sensitive indicator of disease activity. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2002, 47, 198–208.

- Koppes, S.A.; Brans, R.; Ljubojevic Hadzavdic, S.; Frings-Dresen, M.H.; Rustemeyer, T.; Kezic, S. Stratum corneum tape stripping: Monitoring of inflammatory mediators in atopic dermatitis patients using topical therapy. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2016, 170, 187–193.

- Somjorn, P.; Kamanamool, N.; Kanokrungsee, S.; Rojhirunsakool, S.; Udompataikul, M. A cream containing linoleic acid, 5% dexpanthenol and ceramide in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. Asian Pac. J. Allergy Immunol. 2021.

- Iwamoto, K.; Moriwaki, M.; Miyake, R.; Hide, M. Staphylococcus aureus in atopic dermatitis: Strain-specific cell wall proteins and skin immunity. Allergol. Int. 2019, 68, 309–315.

- Williams, M.R.; Gallo, R.L. The role of the skin microbiome in atopic dermatitis. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2015, 15, 65.

- Yamazaki, Y.; Nakamura, Y.; Núñez, G. Role of the microbiota in skin immunity and atopic dermatitis. Allergol Int. 2017, 66, 539–544.

- Byrd, A.L.; Belkaid, Y.; Segre, J.A. The human skin microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 143–155.

- Kong, H.H.; Oh, J.; Deming, C.; Conlan, S.; Grice, E.A.; Beatson, M.A.; Nomicos, E.; Polley, E.C.; Komarow, H.D.; Murray, P.R.; et al. Temporal shifts in the skin microbiome associated with disease flares and treatment in children with atopic dermatitis. Genome Res. 2012, 22, 850–859.

- Eberlein-König, B.; Schäfer, T.; Huss-Marp, J.; Darsow, U.; Möhrenschlager, M.; Herbert, O.; Abeck, D.; Krämer, U.; Behrendt, H.; Ring, J. Skin surface pH, stratum corneum hydration, trans-epidermal water loss and skin roughness related to atopic eczema and skin dryness in a population of primary school children. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2000, 80, 188–191.

- Surber, C.; Humbert, P.; Abels, C.; Maibach, H. The acid mantle: A myth or an essential part of skin health? Curr. Probl. Dermatol. 2018, 54, 1–10.

- Lukić, M.; Pantelić, I.; Savić, S.D. Towards optimal pH of the skin and topical formulations: From the current state of the art to tailored products. Cosmetics 2021, 8, 69.

- Karna, R.V. The investigation on correlation between pH and the likelihood of developing atopic dermatitis on paediatrics and adults population in Indonesia. In Proceedings of the Asian Australasian Regional Conference of Dermatology, Surabaya, Indonesia, 8–11 August 2018.

- Sparavigna, A.; Setaro, M.; Gualandri, V. Cutaneous pH in children affected by atopic dermatitis and in healthy children: A multicenter study. Skin Res. Technol. 1999, 5, 221–227.

- Panther, D.J.; Jacob, S.E. The importance of acidification in atopic eczema: An underexplored avenue for treatment. J. Clin. Med. 2015, 4, 970–978.

- Gupta, J.; Margolis, D.J. Filaggrin gene mutations with special reference to atopic dermatitis. Curr. Treat. Options Allergy 2020, 7, 403–413.

- Gunnarsson, M.; Mojumdar, E.H.; Topgaard, D.; Sparr, E. Extraction of natural moisturizing factor from the stratum corneum and its implication on skin molecular mobility. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 604, 480–491.

- Maeno, K. Direct quantification of natural moisturizing factors in stratum corneum using direct analysis in real time mass spectrometry with inkjet-printing technique. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 17789.

- van Zuuren, E.J.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Christensen, R.; Lavrijsen, A.; Arents, B.W.M. Emollients and moisturisers for eczema. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 2, CD012119.

- Xu, S.; Kwa, M.; Lohman, M.E.; Evers-Meltzer, R.; Silverberg, J.I. Consumer Preferences, Product Characteristics, and Potentially Allergenic Ingredients in Best-selling Moisturizers. JAMA Dermatol. 2017, 153, 1099–1105.

- Draelos, Z.D. The science behind skin care: Moisturizers. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2018, 17, 138–144.

- Shi, V.Y.; Tran, K.; Lio, P.A. A comparison of physicochemical properties of a selection of modern moisturizers: Hydrophilic index and pH. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2012, 11, 633–636.

- Pinter, A.; Thouvenin, M.-D.; Bacquey, A.; Rossi, A.B.; Nocera, T. Tolerability and efficacy of a medical device repairing emollient cream in children and adults with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis. Dermatol. Ther. 2019, 9, 309–319.

- Rossi, A.B.; Bacquey, A.; Nocera, T.; Thouvenin, M.D. Efficacy and tolerability of a medical device repairing emollient cream associated with a topical corticosteroid in adults with atopic dermatitis: An open-label, intra-individual randomized controlled study. Dermatol. Ther. 2018, 8, 217–228.

- European Commission. Medical devices: Guidance Document—Classification of Medical Devices; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2010.

More