You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Sirius Huang and Version 1 by Gao Dashuang.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, inflammatory synovitis-based systemic immune disease of unknown etiology. In addition to joint pathological damage, RA has been linked to neuropsychiatric comorbidities, including depression, schizophrenia, and anxiety, increasing the risk of neurodegenerative diseases in life.

- rheumatoid arthritis

- affective disturbance

1. Psychiatric Comorbidities

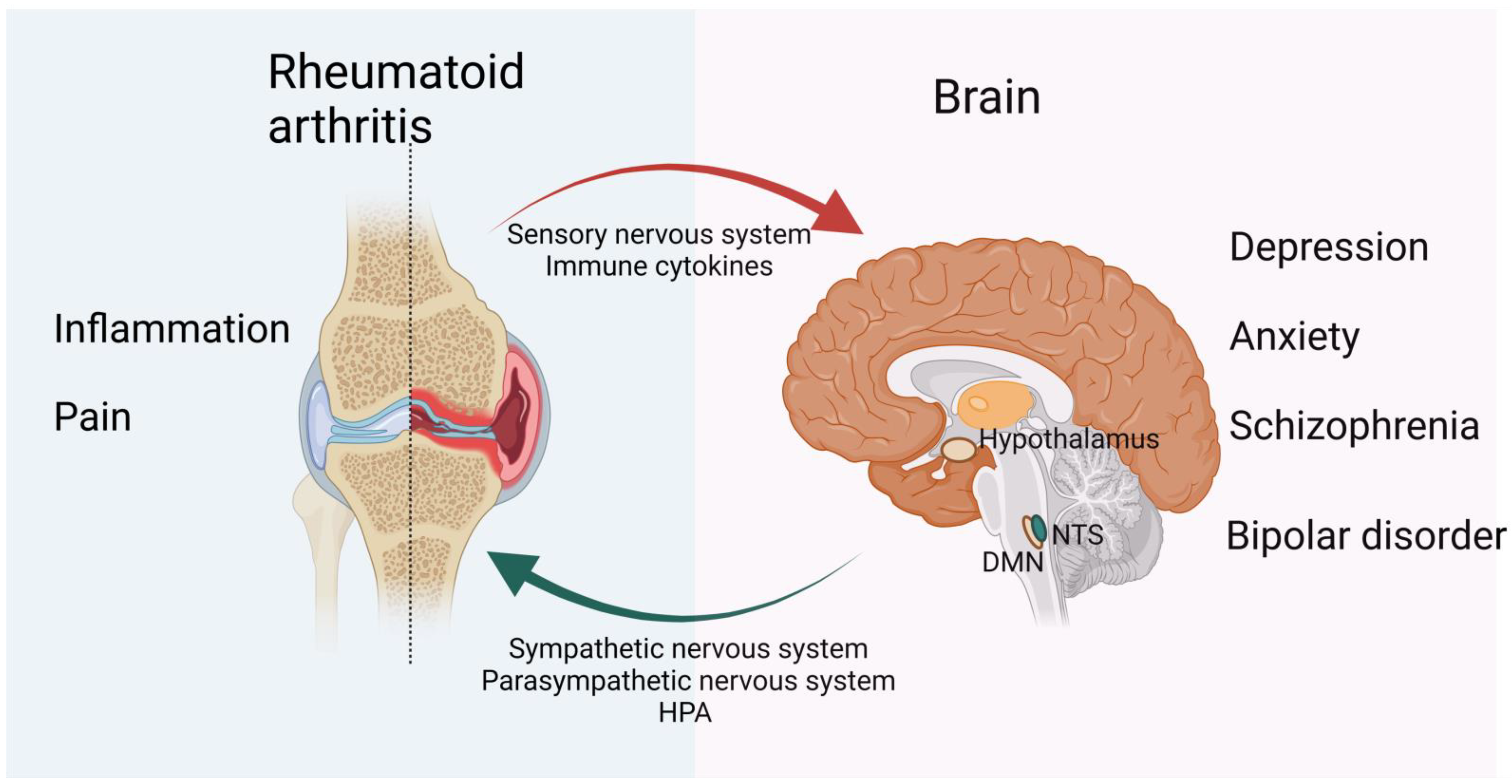

Compared with the general population, rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients are known to endure a higher chance of developing psychiatric comorbidities including depression [11][1] and anxiety, mood, and psychotic disturbances [12][2], which greatly reduce the quality of life and physical and mental health. Compared with people without physical defects or recurring pain [13][3], mental health disorders in RA patients are associated with harmful effects such as pain, fatigue, impaired sleep quality, increased mental health-related distress, and passive pain-coping strategies [14,15][4][5]. Psychiatric comorbidities also adversely affect multiple outcomes in RA patients [16][6], including poor medication adherence and treatment response (Figure 1) [17][7]. For example, RA patients with depression are associated with an inferior response to biological therapy [18][8].

Figure 1. Bidirectional psychological and neurological effects of RA and the brain on each other. Recurrent pain and prolonged inflammation are prominent symptoms of RA and are strongly associated with mental illnesses such as depression and anxiety. In contrast, mental health can influence RA disease activity and is associated with reduced treatment response in RA patients. For example, patients with depression have an increased risk of RA, while antidepressants are reported to have a protective and therefore confounding effect on RA. The CNS and PNScentral nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system (PNS) both play a role in inflammation. The vagus nerve is the main efferent pathway that mediates immunosuppression of the CNS. It controls the production of TNF and other proinflammatory cytokines through the splenic nerve. Sensory nerves are activated by proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1 and IL-6, and sensory immune information is then sent to regions of the brain and spinal cord to mount an appropriate response. The HPA axis and SNS then carry information from the CNS to the PNS. While the parasympathetic nervous system is anti-inflammatory in the first phase of inflammation, its role in the later phases of chronic inflammation requires further research. Figure created using BioRender (https://biorender.com, accessed on 20 July 2022).

Depression and anxiety disorders are relatively well-recognized and studied psychiatric disorders in RA patients. However, due to many reasons, the estimated prevalence of these two differs rather largely from study to study, the incidence of anxiety and depression in RA patients appears to range from 26% to 46% and 14.8% to 34.2%, respectively [19][9]. In addition, the etiology behind it has not been adequately studied [20][10].

2. Depression

Among the related psychiatric disorder in RA, depression is the most closely associated one [21][11]. However, estimates of the prevalence of depression are influenced by many factors, including differences in measurement methods, recurrence of depressive symptoms, and variances in disease duration [19][9]. In addition, there are some overlapping diagnostic symptoms existing both in RA and depression, such as fatigue, poor appetite, and sleeping disturbance, thus some studies have removed items that may overlap between the two diseases or adjusted diagnostic thresholds, inevitably affecting the prevalence statistics of RA patients and depression [22][12].

Nonetheless, the evidence for the negative impacts of depression on the course of RA is convincing. Notably, previous studies have shown that depression accounts for 6.9% of mortality in RA patients [23][13] and is associated with increased mobility in RA, impaired quality of life, reduced chance of remission and increased arthritis-related complications [24][14]. The feelings of hopelessness and non-adherence to treatment caused by depression can also further aggravate the disease, which may explain why patients with moderate, severe, or people with chronic depression are less likely to follow medical guidance than people with mild or no depression, regardless of the medical condition [25][15]. For example, people with rheumatoid arthritis who suffer from chronic depression are less likely to take their doctor’s advice and are less likely to take disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) as prescribed than patients with milder or subclinical levels of depression. According to the inflammatory hypothesis, depression may also be responsible for the increase in inflammation and disease activity in RA [26][16].

In recent years, several studies have also found a bidirectional relationship between depression and rheumatoid arthritis. Notably, in addition to the high incidence of depression in RA patients, people with depression are at greater risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis than the general population [27][17], and antidepressants are reported to have a protective and therefore confounding effect on RA [28][18]. In addition, excessive activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis due to cytokine activity has also been associated with depression [29][19].

3. Anxiety

The prevalence of psychological comorbidities in RA patients has been extensively researched, particularly depression and anxiety [20][10]. Several studies have noted that anxiety is more common than depression in people with rheumatoid arthritis [30][20]. The prevalence of anxiety in RA patients, however, differs across research from 20% to 26% of patients classified as having obvious anxiety disorders or anxiety-like symptoms [31,32][21][22]. In addition, depressed RA patients are more likely to experience symptoms of anxiety compared with general RA patients or age-matched individuals [20][10].

Anxiety in RA patients is related to multiple factors, such as age, sex, socioeconomic status, pain, marital status, and disease activity [32,33,34][22][23][24]. Anxiety symptoms in RA patients are linked to a lower quality of life [35][25] and poor therapeutic response, which are similar to depression. For example, persistent anxiety in RA patients can reduce treatment response to prednisolone by 50% [36][26].

Research on anxiety shares common problems with depression, such as small populations with various prevalence estimates [19][9] and overlapping diagnostic symptoms. Regarding the impact of RA on patient anxiety, studies have reported that c-reactive protein (CRP) levels may be correlated with anxiety and depression levels in RA patients [34][24]. However, it is still unclear if RA increases the prevalence of anxiety independently or if this association is confounded by the anxiety tendencies that are already existed [37][27], and thus more research is needed.

4. Schizophrenia

In comparison to the general population, patients with RA have a rather low prevalence of schizophrenia, according to clinical and epidemiological studies [38][28]. The risk of RA in schizophrenic patients is estimated to be 30–50% of the control [39][29]. One common theory to explain this is the abnormal inflammatory cytokine profile in schizophrenia patients, which includes circulating proinflammatory cytokines [40][30], elevated levels of soluble IL-2 receptor, aberrant tryptophan metabolism, prostaglandin insufficiency, and therapy side effects that are linked to RA-schizophrenia [41][31]. As noted previously, high blood concentrations of IL-1 receptor antagonists may have protective effects against RA in schizophrenic patients [42][32].

Genetics is another important factor in both diseases. Notably, based on the well-studied human leucocyte antigen (HLA) system [43][33], HLADRB1*0101, HLA-DRB1*04 (*0401, *0403, *0405, and *0406), and HLA class II antigens and alleles have been implicated in the regulation of antibody-mediated immune responses [44][34]. HLA-DRB1, including HLA-DR4 serotypes, positively correlated with RA incidence and negatively correlated with schizophrenia levels [45][35]. Therefore, it could be assumed that the negative genetic correlation between RA and schizophrenia may be due to the different roles of variants in immune response pathways in different tissues and/or in response to different challenges [41][31].

5. Bipolar Disorder

Although autoimmune diseases are associated with psychiatric disorders, especially depression and anxiety, little research has been done on the relationship between rheumatoid arthritis and bipolar disorder [46][36]. In addition, asthma, cirrhosis, and alcoholism are important risk factors for developing bipolar disorder [47][37].

Research has also suggested that peripheral chronic inflammation is a key factor in the pathophysiology of CNS inflammation in bipolar disorder [48][38]. Thus, RA is a disease characterized by long-term chronic inflammation, and the process of inflammatory immune response activated by RA may affect the prognosis and development of bipolar disorder.

Sex-related characteristics have also been found to play a key role in developing bipolar disorder in RA patients. Bipolar disorder is equally prevalent in men and women, according to epidemiological studies [49][39]. Female RA patients are more likely to acquire bipolar disorder compared to women without RA. This may be due to sex steroid hormones, which play an important regulatory role in immune responses; specifically, estrogen-induced immune stimulation in RA may be more likely to trigger inflammation [50][40]. However, further clinical and basic research is needed on the relationship between RA and bipolar disorder.

References

- Van, L.; Verdurmen, J.; Have, T. The association between arthritis and psychiatric disorders; results from a longitudinal population-based study. J. Psychosom. Res. 2010, 68, 187–193.

- Postal, M.; Costallat, L.T.L.; Appenzeller, S. Neuropsychiatric Manifestations in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. CNS Drugs 2011, 25, 721–736.

- Lee, Y.C.; Lu, B.; Edwards, R.R.; Wasan, A.D.; Nassikas, N.J.; Clauw, D.J.; Solomon, D.H.; Karlson, E.W. The role of sleep problems in central pain processing in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2014, 65, 59–68.

- Rupp, I.; Boshuizen, H.C.; Roorda, L.D.; Dinant, H.J.; Bos, G.V.D. Poor and good health outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis: The role of comorbidity. J. Rheumatol. 2006, 33, 1488.

- Löwe, B.; Willand, L.; Eich, W.; Zipfel, S.; Fiehn, C. Psychiatric comorbidity and work disability in patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Psychosom. Med. 2004, 66, 395.

- Marrie, R.A.; Hitchon, C.A.; Walld, R.; Patten, S.B.; Bolton, J.M.; Sareen, J.; Walker, J.R.; Singer, A.; Lix, L.M.; El-Gabalawy, R. Increased Burden of Psychiatric Disorders in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2018, 70, 970–978.

- Mattey, D.L.; Dawes, P.T.; Hassell, A.B.; Brownfield, A.; Packham, J.C. Effect of psychological distress on continuation of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J. Rheumatol. 2010, 37, 2021–2024.

- Faith, M.; Rebecca, D.; Matthew, H.; Hyrich, K.L.; Sam, N.; Sophia, S.; James, G. The relationship between depression and biologic treatment response in rheumatoid arthritis: An analysis of the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. Rheumatology 2018, 57, 835–843.

- Faith, M.; Lauren, R.; Sophia, S.; Matthew, H. The prevalence of depression in rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology 2013, 52, 2136–2148.

- Vandyke, M.M.; Parker, J.C.; Smarr, K.L.; Hewett, J.E.; Johnson, G.E.; Slaughter, J.R.; Walker, S.E. Anxiety in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010, 51, 408–412.

- Covic, T.; Cumming, S.R.; Pallant, J.F.; Manolios, N.; Emery, P.; Conaghan, P.G.; Tennant, A. Depression and Anxiety in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: A comparison of the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS) and the Hospital, Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). BMC Psychiatry 2012, 12, 6.

- Geisser, M.E.; Roth, R.S.; Robinson, M.E. Assessing depression among persons with chronic pain using the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale and the Beck Depression Inventory: A comparative analysis. Clin. J. Pain 1997, 13, 163–170.

- Ann, M.R.; Randy, W.; Bolton, J.M.; Jitender, S.; Patten, S.B.; Alexander, S.; Lix, L.M.; Hitchon, C.A.; Renée, E.-G.; Alan, K. Psychiatric comorbidity increases mortality in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2018, 53, 65.

- Sambamoorthi, U.; Shah, D.; Zhao, X. Healthcare burden of depression in adults with arthritis. Expert Rev. Pharm. Outcomes Res. 2017, 17, 53–65.

- Dimatteo, M.R.; Lepper, H.S.; Croghan, T.W. Depression Is a Risk Factor for Noncompliance With Medical Treatment: Meta-analysis of the Effects of Anxiety and Depression on Patient Adherence. Arch. Intern. Med. 2000, 160, 2101–2107.

- Rathbun, A.M.; Reed, G.W.; Harrold, L.R. The temporal relationship between depression and rheumatoid arthritis disease activity, treatment persistence and response: A systematic review. Rheumatology 2013, 52, 1785–1794.

- Vallerand, I.A.; Patten, S.B.; Barnabe, C. Depression and the risk of rheumatoid arthritis. Lippincott Williams Wilkins Open Access 2019, 31, 279–284.

- Sparks, J.A.; Malspeis, S.; Hahn, J.; Wang, J.; Roberts, A.L.; Kubzansky, L.D.; Costenbader, K.H. Depression and subsequent risk for incident rheumatoid arthritis among women. Arthritis Care Res. 2020, 73, 78–89.

- Du, X.; Pang, T.Y. Is Dysregulation of the HPA-Axis a Core Pathophysiology Mediating Co-Morbid Depression in Neurodegenerative Diseases? Front. Psychiatry 2015, 6, 32.

- Murphy, L.B.; Sacks, J.J.; Brady, T.J.; Hootman, J.M.; Chapman, D.P. Anxiety and depression among US adults with arthritis: Prevalence and correlates. Arthritis Care Res. 2012, 64, 968–976.

- Chandarana, P.C.; Eals, M.; Steingart, A.B.; Bellamy, N.; Allen, S. The Detection of Psychiatric Morbidity and Associated Factors in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Can. J. Psychiatry. Rev. Can. De Psychiatr. 1987, 32, 356–361.

- Roger, H.O.; Erin, F.U.; Chua, A.; Cheak, A.; Mak, A. Clinical and psychosocial factors associated with depression and anxiety in Singaporean patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2011, 14, 37–47.

- Ijaz, H.I.; Yaser, I.M. Depression in Rheumatoid Arthritis and its relation to disease activity. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2015, 31, 393.

- Kojima, M.; Kojima, T.; Suzuki, S.; Oguchi, T.; Oba, M.; Tsuchiya, H.; Sugiura, F.; Kanayama, Y.; Furukawa, T.A.; Tokudome, S.; et al. Depression, inflammation, and pain in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2009, 61, 1018–1024.

- Mok, C.; Lok, E.; Cheung, E. Concurrent psychiatric disorders are associated with significantly poorer quality of life in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Scand. J. Rheumatol. 2012, 41, 253–259.

- Faith, M.; Sam, N.; Scott, D.L.; Sophia, S.; Matthew, H. Symptoms of depression and anxiety predict treatment response and long-term physical health outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis: Secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Rheumatology 2016, 55, 268–278.

- Li, M.; Fan, Y.L.; Tang, Z.Y.; Cheng, X.S. Schizophrenia and risk of stroke: A meta-analysis of cohort studies. Int. J. Cardiol. 2014, 173, 588–590.

- Chen, S.-F.; Wang, L.-Y.; Chiang, J.-H.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Shen, Y.-C. Assessing whether the association between rheumatoid arthritis and schizophrenia is bidirectional: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4493.

- Feigenson, K.A.; Kusnecov, A.W.; Silverstein, S.M. Inflammation and the Two-Hit Hypothesis of Schizophrenia. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2013, 38, 72–93.

- Potvin, S.; Stip, E.; Sepehry, A.A.; Gendron, A.; Bah, R.; Kouassi, E. Inflammatory Cytokine Alterations in Schizophrenia: A Systematic Quantitative Review. Biol. Psychiatry 2008, 63, 801–808.

- Lee, S.H.; Byrne, E.M.; Hultman, C.M.; Kähler, A.; Vinkhuyzen, A.A.; Ripke, S.; Andreassen, O.A.; Frisell, T.; Gusev, A.; Hu, X.; et al. New data and an old puzzle: The negative association between schizophrenia and rheumatoid arthritis. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2015, 44, 1706–1721.

- Dinarello, C.A. The many worlds of reducing interleukin-1. Arthritis Rheum. 2005, 52, 1960–1967.

- Gorwood, P.; Pouchot, J.; Vinceneux, P.; Puéchal, X.; Flipo, R.M.; Bandt, M.; Adès, J. Rheumatoid arthritis and schizophrenia: A negative association at a dimensional level. Schizophr. Res. 2004, 66, 21–29.

- Wright, P.; Nimgaonkar, V.L.; Donaldson, P.T.; Murray, R.M. Schizophrenia and HLA: A review. Schizophr. Res. 2001, 47, 1–12.

- Watanabe, Y.; Nunokawa, A.; Kaneko, N.; Muratake, T.; Arinami, T.; Ujike, H.; Inada, T.; Iwata, N.; Kunugi, H.; Itokawa, M. Two-stage case–control association study of polymorphisms in rheumatoid arthritis susceptibility genes with schizophrenia. J. Hum. Genet. 2009, 54, 62–65.

- Najjar, S.; Pearlman, D.M.; Alper, K. Neuroinflammation and psychiatric illness. J. Neuroinflamm. 2013, 10, 816.

- Hsu, C.C.; Chen, S.C.; Liu, C.J.; Lu, T.; Shen, C.C.; Hu, Y.W.; Yeh, C.M.; Chen, P.M.; Chen, T.J.; Hu, L.Y. Rheumatoid Arthritis and the Risk of Bipolar Disorder: A Nationwide Population-Based Study. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e107512.

- Goldstein, B.I.; Kemp, D.E.; Soczynska, J.K.; Mcintyre, R.S. Inflammation and the Phenomenology, Pathophysiology, Comorbidity, and Treatment of Bipolar Disorder: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2009, 70, 1078–1090.

- Price, A.L.; Marzani-Nissen, G.R. Bipolar disorders: A review. Am. Fam. Physician 2012, 85, 483.

- Cutolo, M.; Sulli, A.; Straub, R.H. Estrogen metabolism and autoimmunity. Autoimmun. Rev. 2012, 11, A460–A464.

More