Light increases the germinability of positively photoblastic seeds and inhibits the germination of negative ones. In an area where plant-generated smoke from fire is a periodically occurring environmental factor, smoke chemicals can affect the germination of seeds, including those that are photoblastically sensitive.

In general, germination is under control of inhibitors involved in seed dormancy (mostly abscisic acid, ABA, and auxin, IAA), while gibberellic acid (GA) stimulates the process. Light, via the phytochrome system positively affects GA and decreases ABA and IAA levels. Similarly, karrikin1 (KAR1), physiologically active smoke compound, regulates some light-induced genes which results in germination of positively photoblastic seeds in darkness. However, other smoke compounds and different light spectrum (including blue light) can also affect germination of different species which makes the phenomenon of stimulatory effect of smoke on seeds more complex an still worthy to be studied on different levels.

- seed germination

- smoke compounds

- karrikin

- photoblastism

- smoke formulations

1. Introduction

2. The Impact of Smoke Formulations and Isolated Smoke Compounds on the Germination of Photoblastic Seeds

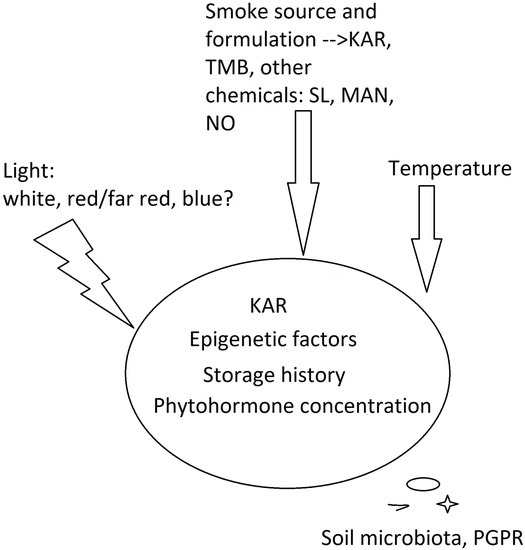

The first data linking smoke with its ability to substitute light for positively photoblastic seeds of ‘Grand Rapids’ lettuce come from Drewes et al. [10] and Jäger et al. [11]. They laid the foundation for further research with the use of seed lots of different origin and to check the red/far red (R/FR) seed response to establish the involvement of the phytochrome system in smoke-stimulated seed germination. Merrit et al. [25] provided evidence that KAR1 acts in a similar manner as gibberellic acid when stimulating the germination of some Australian plants. Over the last thirty years, the research also included species of different habitats. Do smoke compounds and light act in concert, or can smoke emulate the impact of light? This is difficult to answer based on the literature data. The use of photoperiod for seeds of unknown or undefined photoblastism was probably due to the involvement of natural daylength occurring in the specific area. Light source, that is, light spectrum and intensity, varied in different experiments. The seeds were kept under natural light, artificial white light or fluorescent light, which introduced variability among the compared studies. This is discussed in Section 5. While looking for other factors differentiating the experiments on photoblastic seeds, smoke formulations and isolated compounds were noticed. When an experimental treatment involves smoke-infused water or smoke fumigation, the question arises as to what should be used as a control. The first attempt toward this was made by Jäger et al. [11]. Aqueous smoke extracts were prepared from a range of plants, and the extracts from agar and cellulose were used. All of them stimulated the germination of lettuce, and a chromatographic analysis indicated the presence of the same compounds, which was a big step towards the discovery of KARs. Today, it is known that the chemical composition of the smoke varies due to specific secondary metabolites and different amounts of various carbohydrates, that is KAR and TMB precursors [26][27][28][26,27,28]. In paper [29], smoke water from two plants, white willow and lemon eucalyptus, was used, and the authors reached the same results in the seeds of different horticultural crops. The author of [30] reported no difference in the effects of smoke that was generated by burning laboratory filter paper or dried meadow sward, which eliminated the potential stimulatory impact of coumarins, secondary metabolites that are abundant in grasses, on germination [31]. In another experiment, [32] the smoke water of an Australian grass, Themeda triandra (Poaceae), was used to treat the seeds of a cosmopolitan persistent weed, Avena fatua, of Eurasian origin. As reported by Long et al. [33], KAR1 is a smoke-derived compound that is physiologically active toward the seeds of A. fatua, so the impact of smoke water on its seeds is independent of the type of plant material that is used for smoke generation [33]. Experiments employing liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry systems for qualitative and quantitative analysis proved that smoke that was obtained from different plant residues may have different properties [34][41]. Taking this into account, Gupta et al. [27] proposed a method to standardize the SW composition for seed germination and plant growth stimulation based on a ‘Grand Rapids’ lettuce bioassay, and to estimate the levels of stimulatory (KAR1 and KAR2) and inhibitory (TMB) compounds using a UHPLC-ESI(+)-MS/MS analysis. Considering the specificity of the response of positively photoblastic seeds, seven global weeds: Avena fatua, Lolium rigidum, Eragostis curvula, Phalaris minor, Hordeum glaucum, Ehrharta calycina, and Bromus diandrus to karrikinolide (probably KAR1) seem highly interesting [33]. The germination of A. fatua non-dormant seeds was consistently stimulated by KAR in different experiments. On the contrary, the seeds of L. rigidum were not stimulated by KAR in any case. A different response was observed in E. curvula. Its seeds were unaffected by KAR when freshly collected from the maternal plant, but the dormant ones responded to KAR after cold stratification. All the findings pointed to the conclusion that the response of grasses depended on the species, temperature, presence or absence of light, seed storage history (which implies seed burial and low temperature), and KAR concentration. Another important conclusion was that the so-called window of suitable conditions for responding to KAR was narrow, which is discussed in detail in Section 3. Hidayati et al. [35][36] revealed a stimulating effect of both KAR1 and aerosol smoke on the seeds of Hibbertia sp. (shrubs of Dilleniaceae family), whose germination is very slow (1–2 months for seedling emergence). Some Hibbertia plants producing positively photoblastic seeds responded to both treatments, but aerosol smoke provided better results. This means that not only KAR1, but also other smoke-derived compounds stimulated seed germination. In this resea rch and a paper [18], the interest is in the mode of action of different compounds acting individually (KARs, benzaldehydes, cyanohydrins and nitrates) or in concert when aerosol smoke or smoke-saturated water (smoke water, SW) is used. Technically, aerosol smoke and SW contain the same compounds as gaseous products of combustion. However, during storage, various chemical reactions may occur in SW and alter its chemical composition. From a cognitive point of view, such an approach seems interesting, as emphasized already in 2010 by Dayamba et al. [26]. On the other hand, in the research focusing on the cellular mechanism of smoke action in seeds, and in experiments of practical importance, special attention is paid to the impact of substances that are isolated from smoke to obtain reproducibility. This seems justified, as smoke formulations produce different results due to the variable content of germination stimulants and inhibitors [17][23][24][17,23,24]. Following this path of thinking raises another question: do different smoke-derived, physiologically active chemicals act in the same way in photoblastic seeds? To address this query, Tavşanoğlu et al. (2017) [21] studied both KAR1 and a cyanohydrin analogue, mandelonitrile (MAN), in the seeds of an annual plant, Chaenorhinum rubrifolium, that was characterized by strong physiological dormancy. Other factors, such as mechanical scarification, heat shock, aqueous smoke, nitrogenous compounds, gibberellic acid (GA), darkness, and photoperiod conditions were also considered. KAR and MAN stimulated the germination of Ch. rubrifolium, used both individually and in combination, and the highest germination rate was achieved by a joint treatment with KAR1 and light. Moreover, heat shock and smoke combinations also had positive synergistic and additive effects on germination under light conditions. Therefore, not only the smoke-specific molecules but also environmental factors characteristic of the local environment must be considered (Figure 1).