Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Isaac Akomea-Frimpong and Version 3 by Vivi Li.

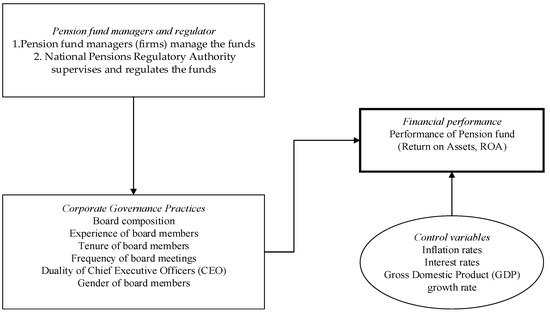

Corporate governance has been explained as a mechanism by which operational managers of entities are made to act in the interest of the owners of the entities and other stakeholders. Good stewardship and sustained accountability are expected from firms by society. In pension fund management settings, two sets of factors affect corporate entity’s effectiveness. The first is the internal corporate governance factors relating to pension fund management. This involves effective interactions between internal systems relating to pension funds. The second factor is the external corporate governance factors concerning the regulatory and legal framework under which the pension funds operate.

- corporate governance

- mixed method

- pension funds

- performance

- sustainability

1. Introduction

Sound corporate governance is a great concern of every stakeholder (Claessens and Yurtoglu 2013; Cocco and Volpin 2007; Phan and Hegde 2012) Good corporate governance practices contribute to corporate success, maximise shareholder wealth, promote a positive corporate image, and maintain investors’ confidence (Abor 2007). Abor and Adjasi (2007) indicated that the primary role of good corporate governance is its focus on the supervision and accountability of managers of a firm. In addition, good corporate governance serves as a tool to mitigate corrupt practices and encourage adherence to ethical codes (Arjoon 2017; Darko et al. 2016; Kowalewski 2016; Sami et al. 2011; Soana 2011). Additionally, Adams and Mehran (2012) found that effective corporate governance mechanisms in a company reduce operational costs and increase a firm’s profitability. Furthermore, studies on corporate governance have shown that board composition (i.e., age, experience, gender), Chief Executive Officer (CEO) or chairman split, non-executive directors, and audit committees are critical indicators to boost a firm’s performance (Abor 2007; Alves and Mendes 2004; Denis 2001; Giannarakis 2014). On the other hand, poor corporate governance entrenches poor mishandling of earnings, resulting in bad corporate image and financial capital. For its importance, Škare and Hasić (2016) assert that corporate governance ensures a better relationship among of all stakeholders.

Empirical evidence reveal that corporate governance and firm performance are inconclusive, and these studies have shown mixed results (Alabdullah 2018; Buallay et al. 2017). From a positive perspective, studies found corporate governance characteristics to significantly impact the performance of firms (Ahmed and Hamdan 2015; Gupta and Sharma 2022). A research study by Buallay et al. (2017) in Saudi Arabia using 171 listed firms demonstrated that more robust corporate governance systems of a firm significantly improve its performance. However, other studies found little or no impact of corporate governance on the performance of firms (Aldamen et al. 2011; Black et al. 2006). Studies are skewed against the pension fund sector in comparative with much research geared toward other sectors such as banks, manufacturing, etc. in developed economies (Buallay et al. 2017). In emerging economies such as Ghana, few studies exist on the role good corporate governance plays in the performance of pension funds (Abor and Adjasi 2007; Anku-Tsede 2019).

A review of the literature revealed that the relationship between corporate governance practices and the management of pension funds is not clear in research outlets in Ghana (Dorfman 2015; Mpinga and Westerman 2017). As in other emerging economies (Dorfman 2015; Mpinga and Westerman 2017; Phan and Hegde 2012), the pension industry in Ghana is still evolving due to the limited income of the labour force, which is not interested in setting aside funds to cater for pensions (Stewart and Yermo 2009). Numerous factors have been identified as accounting for this phenomenon, which include including an aging population, income disparities, mismanagement of pension funds, political interference, and low investment returns (Anku-Tsede 2019). A national pension reform was kick-started from 2004 to 2009, and the outcomes of the reforms was the Pension Act 766 in 2010 that received an amendment in 2014, Act 883 (Donkor-Hyiaman et al. 2019). Ghana’s pension scheme is a three-tier pension scheme. The government manages the first tier and second tier through Social Security and National Insurance Trust (SSNIT) and approved pension fund managers(Ashirifi et al. 2021; Kpessa-Whyte and Tsekpo 2020). The third tier is a voluntary scheme managed personally or the selected pension fund manager of the pensioner (Kpessa-Whyte 2011). From a modest sum of GH¢805.1 million in 2012, tier two and three pension fund contributions in Ghana managed by private schemes rose to GH¢2.6 billion in 2014 before closing in 2015 at GH¢6.8 billion (NPRA 2015).

Additional data from the National Pensions Regulatory Authority (NPRA) showed that GH¢8.3 billion was recorded in 2017 with GH¢2.7 billion contributions from funds managed by pension funds, and the amount has doubled as of 2021. However, studies and institutional reports have not established the contribution of corporate governance to this growth. Notably, the sustainability of pension funds in Ghana appears to be fragile due to the changing global events and occurrences such as COVID-19 that put returns on pension funds at risk (Kpessa-Whyte 2011). Therefore, this enstrudy’s aim is to assess the relationships between corporate governance practices and the performance of pension funds in Ghana. The specific objectives include: (1) to determine the dominant corporate governance practices of pension funds in Ghana, (2) to examine the impacts of corporate governance on the performance of pension funds in Ghana, and (3) to establish the challenges associated with corporate governance practices of pension funds in Ghana. The study’s contribution is mainly twofold: First, it highlights the key contribution of corporate governance practices of pension funds in an emerging economy. To the best of researchers'our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the impact of corporate governance practices on pension funds’ performance in Ghana. In addition, the study complements existing literature on corporate governance by providing specific practices that enhance the performance of firms. Researchers'Our study specifically indicates that the board composition and frequency of board meetings ensures relevant management decisions are made to strengthen the firm’s performance and ensure a better stakeholder relationship. These practices provide understanding of the role of sound corporate governance in the performance of pension funds. Secondly, the findings of this research are relevant to fund managers in knowing the key corporate governance practices for pension funds’ performance. Importantly, this research will inform the formulation of new policies and the revision of existing practices of pension funds to achieve better corporate outcomes. The remaining sections of the study include a literature review, methodology, results, and conclusions of the study.

2. Evolution of Pension Funds in Ghana

Pensions in Ghana started as far back as the colonial era to cater for those who worked in the colonial administration and mine workers (Kpessa-Whyte 2011). It was a non-contributory scheme that was exclusive and available to only urban dwellers, mostly the Europeans and a few Africans, to reward and encourage loyalty. In 1950, the first pension scheme, the Pension Ordinance No. 42 (Cap 30) and Superannuation schemes were introduced to cater for the retirement benefit of Ghanaian public workers, such as teachers, university lecturers, doctors, and nurses; however, a clear majority of Ghanaians were unable to benefit from this scheme (Ashidam 2011). The Social Security Act (No. 279) was passed in 1965 to cover all private and public-sector workers who were not covered under the previous scheme. It was a provident fund, providing benefits for old age, invalidity and survivor benefit. This scheme was revoked, and the Social Security and National Insurance Act (SSNIT) was established under NRCD 127. In 1991, the Social Security Act was enacted, and the scheme was turned into a defined contribution scheme (Donkor-Hyiaman et al. 2019). However, some workers such as the Armed Forces, Police and Prison Service were exempted from joining the scheme. Ghana operates three pension benefits: Old Age Benefit, Invalidity Benefit, and Death Survivor Payment. To qualify for the old age benefit under the new scheme, a worker must have worked for a minimum of 240 months and be at least 60 years of age, while those in the mines and other extractive industries have a mandatory retirement age of 58. Workers who have been injured at work may qualify for payment under the invalidity benefit section of the social security system (Mensah 2013). If a worker dies before the required retirement age, their benefits are calculated as the present value of all contributions and paid as a lump sum to the surviving spouse or dependents; this is known as the death survivor payment. Funding of the schemes is based on contributions made by the employer and the employee on behalf of the employee. The employer contributes 12.5% of the employee’s salary, while the employee contributes 5% of their salary, totalling 17.5%. These contributions are invested, and when the employee reaches retirement age, becomes permanently incapacitated or dies before retirement, the total contributions and returns on the investment are paid as a lump sum to the employee or their dependents (Kpessa-Whyte 2011). Over the years, concerns have been raised about SSNIT not paying enough benefits to retirees and failing to include informal sector workers, who constitute about 80% of the workforce in the scheme; this led to a reform in July 2004. This led to the drafting and passing of the National Pensions Act 2008 to provide universal pensions to all Ghanaian workers (Kpessa-Whyte 2011). The Act is divided into four parts; the first discusses having a regulatory body. The second part deals with the provision of the schemes, the third part deals with the management of the schemes, and finally, the general provisions of the Act are contained in the fourth part. Under the new scheme, 18.5% of a worker’s monthly salary will be paid towards their pension, which is distributed between the first and second tiers. The first two tiers are mandatory, and the third tier is voluntary. The first tier, which makes up 13.5% of an employee’s monthly salary, goes to SSNIT, and it is mandatory for both public and private sector workers. Still, self-employed individuals have the option of joining or not. Out of the 13.5%, 2.5% goes to the NHIS, and 5% of an employee’s monthly salary is allocated to the second tier, which is managed privately by approved pension fund managers. The aim is to give pensioners lump sum benefits compared to what is presently available under the SSNIT. The third tier is a voluntary provident fund and personal pension scheme, which provides tax benefit incentives for workers who opt for this scheme and the first two (Dorfman 2015). It could be managed personally or by approved pension fund managers. The previous pension schemes in Ghana were relatively exclusive and did not cover 80% of Ghana’s working population. The introduction of the Authority and the third tier is an effort to address the issues concerning the old pensions system, which by design excluded those in the informal sector and did not provide avenues for the citizenry to arrange their pensions in addition to the state pension. In this case, pension fund managers (firms) oversee the pensions of citizens who want to attain better pension outcomes during retirement. All pension fund managers in Ghana are required registered to register individually as limited liability firms under the Companies Act, 2019 and seek additional certifications of operation from National Pensions Regulatory Authority (NPRA 2022). There are no limitations on the forms on registrations, but it must be prescribed by the NPRA and the Companies Act, 2019 (Kpessa-Whyte and Tsekpo 2020). There are no legal restrictions on where investments can be made, as far as it is a legitimate investment venture (Kpessa-Whyte 2011).3. Corporate Governance of Pension Funds

Corporate governance has been explained as a mechanism by which operational managers of entities are made to act in the interest of the owners of the entities and other stakeholders (Aboagye and Otieku 2010). The authors alluded that the organisations with good corporate governance structures report better performance, implying that when managers take keen interest in putting the right structures in place, the firm performs well. The OECD (2004) also explains corporate governance as “a set of relationships between a company’s management, its board, its shareholders, and other stakeholders. Corporate governance provides the structure through which the company’s objectives are set, and the means of attaining those objectives and monitoring performance are determined” (Alda 2021). Corporate governance includes relations between owners and top management, and these relations make it possible for agents to be accountable to shareholders (Kowalewski 2016). Corporate governance concerns rules and regulations that organisations apply and follow to achieve visions and missions translated into stated objectives for boards of directors and managers of resources. Sound corporate governance encourages the efficient use of resources and accountability for managers’ stewardship of those resources (Ioannou and Serafeim 2012). Institutions that practice good corporate governance are more likely to achieve institutional objectives and goals (Agyemang and Castellini 2015). Kumari and Pattanayak (2017) recommended that shareholders tie the remuneration of board members to their performance and that organisations develop an annual mechanism to check management cum board activities. Kowalewski (2016) advocates the need for a firm (well-informed) board to drive an organisation’s vision with a good sense of judgment in management and performance. Researchers have professed the need for strong corporate governance mechanisms in all aspects of an institution’s life to ensure the diligence and integrity of these entities’ operations. Good corporate governance is now a prime concern to owners and other stakeholders of institutions. These concerns extend to the general welfare of society. Good stewardship and sustained accountability are expected from firms by society. In pension fund management settings, two sets of factors affect corporate entity’s effectiveness. The first is the internal corporate governance factors relating to pension fund management. This involves effective interactions between internal systems relating to pension funds. The second factor is the external corporate governance factors concerning the regulatory and legal framework under which the pension funds operate. The first node in Figure 1 exhibits the managers of pension funds with the regulators from the National Pensions and Regulatory Authority (NPRA), which is a body that supervises pension fund management in Ghana. The National Pension Act 2008 (Act 766) established the National Pensions Regulatory Authority (NPRA) as the sole supervisor (regulator) of pension fund activities in Ghana (Donkor-Hyiaman et al. 2019). The NPRA monitors the operations of all pensions in the country by demanding regular reports from the pension fund managers (Anku-Tsede 2019). The regulatory body also updates the pension managers of new regulatory requirements. It oversees the registration and dissolution of pension fund managers (firms) by invoking various legal codes of the country. The NPRA trains fund managers and monitors the progress of pension funds by reviewing annual reports. The NPRA assigns supervisors to each of the pension funds, and internally, there is a specific manager within the pension fund firms to meet the requirements of the NPRA (NPRA 2022).

Figure 1.

Corporate governance and pension funds.