You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Rita Xu and Version 1 by Rima Hajjo.

The human microbiome encodes more than three million genes, outnumbering human genes by more than 100 times, while microbial cells in the human microbiota outnumber human cells by 10 times. Thus, the human microbiota and related microbiome constitute a vast source for identifying disease biomarkers and therapeutic drug targets.

- biomarkers

- diagnostic biomarkers

- metagenomics

1. Introduction

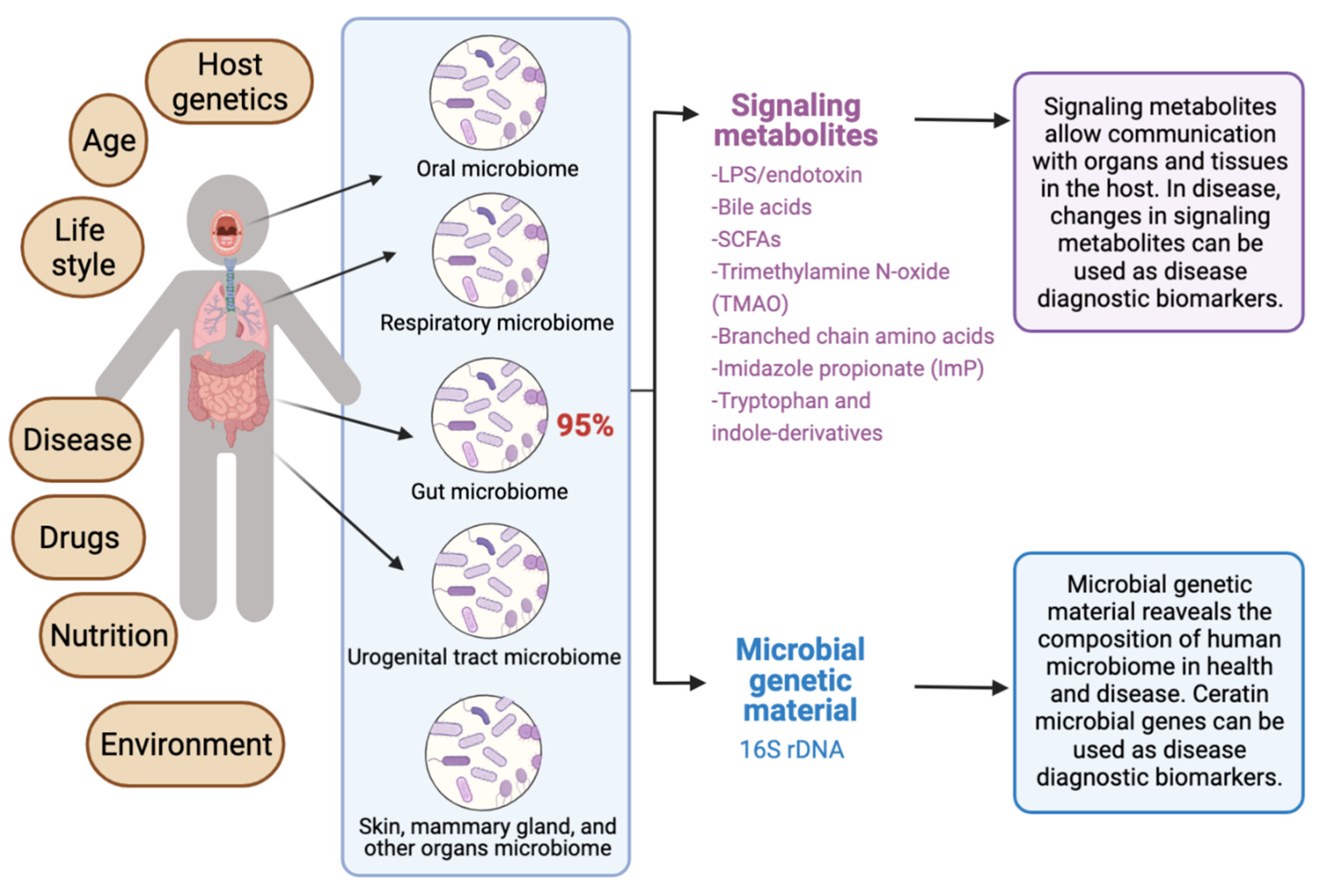

The human microbiota comprises 10–100 trillion symbiotic microbial cells constituting over 10,000 microbial species residing in the human body and outnumbering human cells by 10 times [1]. It consists primarily of bacteria, in addition to viruses, fungi, protozoa, and helminths residing in and on human body organs, such as the skin, mammary glands, mucosa, gastrointestinal (GI), respiratory, and urogenital tracts [2,3,4][2][3][4]. The largest percentage of the human microbiota (95%) resides in the GI tract, and every human being has a unique microbiota composition which could potentially serve as a unique fingerprint. The human microbiome consists of the genes of prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells, and it is often viewed as our “other genome”, which consists of more than three million genes, in comparison with our 23,000 human genes. Hence, the human microbiome has gained increased interest recently with regard to identifying novel drug targets and biomarkers for human disease.

Microbiota affect human health and disease by modulating important metabolic and immunomodulatory processes [3,5][3][5]. The interactions between the human body and microbiota form a complex, distinct, and harmonized bionetwork that defines the relationship between the host and its microbiota as commensal, symbiotic, or pathogenic. The human microbiota is continually developing and changing throughout life by responding to host factors such as age, genes, hormonal changes, nutrition, predisposing disease, lifestyle, and many environmental factors [6,7,8,9][6][7][8][9]. Harmonized microbiota contribute substantially to healthy livelihood [7], while a disruption in microbiota hemostasis (dysbiosis) might contribute to life-threatening diseases [10]. The significant contribution of the human microbiome in health and disease has been recently described in the biomedical literature [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22] delineating gastrointestinal [10,23,24,25,26,27[10][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37],28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37], urinary tract [4[4][38],38], and skin [3] microbiota. Evidence from the biomedical literature indicates that alterations in host immunity might be closely related to the compositional and functional changes of gut flora [24,39][24][39].

Thus, the human microbiota can potentially lead to the discovery of effective disease diagnostic biomarkers. According to the National Institute of Health (NIH), a biomarker is “a characteristic that is objectively measured and evaluated as an indicator of normal biologic processes, pathogenic processes, or pharmacologic responses to a therapeutic intervention” [40]. A diagnostic biomarker is simply a biomarker that “detects or confirms the presence of a disease or condition of interest, or identifies an individual with a subtype of the disease” [41]. The most frequently used biomarkers are derived from either biological materials or imaging data. More recently, machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) have enabled the identification of highly predictive, disease-specific biomarkers [42].

In fact, microflora disturbances have been linked to many human diseases, including GI tract diseases [10,43][10][43], cardiovascular disease [13,44[13][44][45],45], allergies [39[39][46],46], inflammation [44[44][45][47],45,47], neuro-disease, stubborn bacterial infections [48[48][49][50][51],49,50,51], and cancer [37,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68][37][52][53][54][55][56][57][58][59][60][61][62][63][64][65][66][67][68]. Aberrations in the human microbiome are linked to several cancers, including breast, colorectal, gastric, pancreatic, and hepatic cancers [69,70][69][70]. Additionally, cancer could be provoked by viruses, fungi, helminths, and bacteria [69,70][69][70]. Microbiota might also contribute to cancer development by disrupting the balance between the growth and death of host cells after altering the immune system and affecting metabolism [58,71,72][58][71][72]. Furthermore, Microbiota affects cancer prognosis by several mechanisms, including genotoxicity, inflammation, and metabolism [73].

Recent reviews indicated that microbiome signatures can be exploited as disease diagnostic biomarkers [71,72,74,75,76,77,78,79][71][72][74][75][76][77][78][79]. Herein, wresearchers review the available evidence supporting the use of the human microbiome- and microbiota-derived metabolites for the purposes of disease diagnosis. A graphical summary of the concept in provided in Figure 1. WResearchers detail potential microbiota-derived biomarkers for the diagnosis of a variety of diseases, including complex diseases like diabetes, neuro-diseases, and cancer.

Figure 1. Exploiting the human microbiome for diagnostic disease biomarkers.

2. The Rationale for Microbiome-Based Disease Biomarkers

The identification of “ideal biomarkers” is considered a daunting task for many diseases, including some cancer types. Most of the current sampling techniques for cancer tissues cannot identify individuals who will lack response to therapy, and they fall short in classifying cancer types correctly, owing to the inter- and intra-tumor heterogeneity of tumors [80]. A biomarker should be easily measurable, non-invasive, and cost-effective. The human microbiome, particularly the gut microbiome, can be considered as a non-invasive approach to identify disease biomarkers that can detect many diseases in the early stages [71,81][71][81]. Additionally, the identification of microbiome-based biomarkers can increase the accuracy of disease classification when it is combined with clinical information and other biomarkers. For example, some microbes are known to contribute to the adenoma-carcinoma transition in some cancers, such as colorectal carcer (CRC). Such microbes can be exploited as disease and immunotherapy efficacy biomarkers for CRC [71,81][71][81].

In addition to microbiome-based biomarkers, there is also an emerging interest in mast cells (MCs) [82[82][83][84][85],83,84,85], microRNAs (miRNAs) [86,87][86][87], imaging, and machine-learning models [42] as non-invasive disease diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers that promise to shape the future of precision medicine. Sometimes, there is a crosstalk between the human microbiota and other genetic or chemical biomarkers. For example, alterations in fecal small RNA profiles in CRC reflect gut microbiome composition in stool samples [88]. Thus, using multiple connected biomarkers of the network type (i.e., “network biomarkers”) may increase the effectiveness of existing biomarkers.

3. The Significance of Human Microbiota in Health and Disease

The human microbiota plays several important roles in the human body, such as helping in food digestion, producing vitamins, regulating the immune system, and protecting against pathogenic disease-causing microbes. In the following subsections, wresearchers review the significance of the human microbiota in health and disease and the importance of classifying healthy microbiomes from unhealthy microbiomes in clinical practice.

3.1. Conservation of Homeostasis

The human microbiota controls the immune system and affects the inflammatory cascade and immune homeostasis in newborn and children [89]. Children developing allergies at advanced ages showed ubiquity of anaerobic bacteria and Bacteroidaceae, as well as a low number of Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium bifidum, and Bifidobacterium adolescentis [11,27][11][27]. Studies reported that these microbes hydrolyze adulterants such as pesticides, plastic particles, heavy metals, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and organic compounds [23]. Further studies revealed that the urinary tract microbiomes detoxify toxins [90]. Studies showed that female genital tract microbiomes provoke an immune response through secreting antimicrobial peptides, inhibitory compounds, and cytokines [90].

3.2. Involvement in Host Immune System

The symbiosis interaction between the indigenous microbiome and the immune system results in the evolution of immune responses and the development of the immune system to recognize pathogens and beneficial microbiota [91,92][91][92]. Indeed, the immune system is shaped by the human microbiome [93]. The lack or alterations in the human microbiome might weaken the immune system and induce type II immunity responses and allergies [39,94][39][94]. Aberrations of microbiota induce allergic rhinitis in children [39,94][39][94]. The gut microbiome activates the regulatory T-cells (Tregs) and proinflammatory Th17cells in the intestine [95,96][95][96]. The older neutrophil decreases the proinflammatory properties in vivo [91]. The microbiota induces the growth of neutrophil through MyD88-mediated and Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling cascades [91]. Changes in microbial flora decrease the old neutrophils and induce inflammation-mediated tissue injury, such as septic shock and sickle cell disease. Altogether, the microbial flora supervise disease-inducing neutrophil, which is a substantial component in inflammatory diseases [91]. In addition, the gut microbiomes protect the body against harmful pathogens through inducing colonization resistance, as well as synthesizing antimicrobial compounds [97]. A stable intestinal microbiota controls antibodies of CD8+T (killer) and CD4+ (helper) cells that impede the influx of the influenza virus to the respiratory system [89,97][89][97]. The gut flora supports and optimizes the functionality of the GIT [98,99][98][99]. Activating the regulatory T cells is essential in maintaining the hemostasis of the immune system [89].

3.3. Involvement in Host Nutrition and Metabolism

Gut microbiota provide nutrients to the host by digesting complex dietary elements (e.g., fiber and other complex carbohydrates) in food, permitting their absorption from the gut [100]. Additionally, intestinal microbiota offer essential nutrients that are not available, but are necessary for maintaining GI tract functionality [101]. Furthermore, intestinal microbiota halt cancer prognosis in the GI tract by generating butyrate, which is a product of fermentation complex nutrients [102]. Studies revealed that fruits’ and vegetables’ carbohydrates maintain a healthy GI tract microbiome [97]. In addition, the gut microbiome provide the required vitamins (K and folic acid) for host growth, such as enterobacteria and GI tract bacteria, including Bacteroides and Bifidobacterium species [100]. Moreover, gut microbiota contribute to red and white blood cells (RBC and WBC) synthesis [103]. Live microorganisms (probiotics) are deployed for treating allergic diseases [97]. Probiotics decrease and/or inhibit the activation of T-cells and restrain the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) that participates in systemic inflammation [97]. Gut microbiota produce important vitamins needed for blood coagulation, including B vitamins such as B12, thiamine and riboflavin, and Vitamin K [104,105,106][104][105][106].

3.4. Classifying Healthy and Unhealthy Microbiomes

The identification of microbiome-based biomarkers for disease diagnosis, prognosis, risk profiling, and precision medicine relies on the determination of microbial features associated with health or disease. It is often a daunting task to clearly define what constitutes a healthy microbiome in different human populations, especially because a person’s microbiota can be affected by many factors, including age, lifestyle, diet, smoking, exercise, ethnicity, environmental factors, and other factors. Another challenge in classifying healthy versus unhealthy microbiomes stems from limitations in the current technologies and methodologies that do not provide a high microbial resolution on the strain-level, impeding the functional understanding or relevance for health or disease [10].

References

- Turnbaugh, P.J.; Ley, R.E.; Hamady, M.; Fraser-Liggett, C.M.; Knight, R.; Gordon, J.I. The human microbiome project. Nature 2007, 449, 804–810.

- Sender, R.; Fuchs, S.; Milo, R. Are We Really Vastly Outnumbered? Revisiting the Ratio of Bacterial to Host Cells in Humans. Cell 2016, 164, 337–340.

- Byrd, A.L.; Belkaid, Y.; Segre, J.A. The human skin microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 143–155.

- Whiteside, S.A.; Razvi, H.; Dave, S.; Reid, G.; Burton, J.P. The microbiome of the urinary tract—A role beyond infection. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2015, 12, 81–90.

- Al Bataineh, M.T.; Alzaatreh, A.; Hajjo, R.; Banimfreg, B.H.; Dash, N.R. Compositional changes in human gut microbiota reveal a putative role of intestinal mycobiota in metabolic and biological decline during aging. Nutr. Healthy Aging 2021, 6, 269–283.

- Al-Zyoud, W.; Hajjo, R.; Abu-Siniyeh, A.; Hajjaj, S. Salivary microbiome and cigarette smoking: A first of its kind investigation in Jordan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 256.

- Ding, T.; Schloss, P.D. Dynamics and associations of microbial community types across the human body. Nature 2014, 509, 357–360.

- Tarawneh, O.; Al-Ass, A.R.; Hamed, R.; Sunoqrot, S.; Hasan, L.; Al-Sheikh, I.; Al-Qirim, R.; Alhusban, A.A.; Naser, W. Development and characterization of k-carrageenan platforms as periodontal intra-pocket films. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2019, 18, 1791–1798.

- Tarawneh, O.; Hamadneh, I.; Huwaitat, R.; Al-Assi, A.R.; El Madani, A. Characterization of chlorhexidine-impregnated cellulose-based hydrogel films intended for the treatment of periodontitis. Biomed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 9853977.

- Shanahan, F.; Ghosh, T.S.; O’Toole, P.W. The Healthy Microbiome-What Is the Definition of a Healthy Gut Microbiome? Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 483–494.

- Cho, I.; Blaser, M.J. The human microbiome: At the interface of health and disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2012, 13, 260–270.

- Lloyd-Price, J.; Mahurkar, A.; Rahnavard, G.; Crabtree, J.; Orvis, J.; Hall, A.B.; Brady, A.; Creasy, H.H.; McCracken, C.; Giglio, M.G. Strains, functions and dynamics in the expanded Human Microbiome Project. Nature 2017, 550, 61–66.

- Peng, J.; Xiao, X.; Hu, M.; Zhang, X. Interaction between gut microbiome and cardiovascular disease. Life Sci. 2018, 214, 153–157.

- Gilbert, J.A.; Blaser, M.J.; Caporaso, J.G.; Jansson, J.K.; Lynch, S.V.; Knight, R. Current understanding of the human microbiome. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 392–400.

- Kuntz, T.M.; Gilbert, J.A. Introducing the Microbiome into Precision Medicine. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 38, 81–91.

- Ogunrinola, G.A.; Oyewale, J.O.; Oshamika, O.O.; Olasehinde, G.I. The Human Microbiome and Its Impacts on Health. Int. J. Microbiol. 2020, 2020, 8045646.

- Behrouzi, A.; Nafari, A.H.; Siadat, S.D. The significance of microbiome in personalized medicine. J. Transl. Med. 2019, 8, 16.

- Kho, Z.Y.; Lal, S.K. The human gut microbiome–a potential controller of wellness and disease. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1835.

- Liu, Z.; de Vries, B.; Gerritsen, J.; Smidt, H.; Zoetendal, E.G. Microbiome-based stratification to guide dietary interventions to improve human health. Nutr. Res. 2020, 82, 1–10.

- Berg, G.; Rybakova, D.; Fischer, D.; Cernava, T.; Vergès, M.-C.C.; Charles, T.; Chen, X.; Cocolin, L.; Eversole, K.; Corral, G.H.; et al. Microbiome definition re-visited: Old concepts and new challenges. Microbiome 2020, 8, 103.

- Guthrie, L.; Kelly, L. Bringing microbiome-drug interaction research into the clinic. EBioMedicine 2019, 44, 708–715.

- Zangara, M.T.; McDonald, C. How diet and the microbiome shape health or contribute to disease: A mini-review of current models and clinical studies. Exp. Biol. Med. 2019, 244, 484–493.

- Claus, S.P.; Guillou, H.; Ellero-Simatos, S. The gut microbiota: A major player in the toxicity of environmental pollutants? NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2016, 2, 16003.

- Thursby, E.; Juge, N. Introduction to the human gut microbiota. Biochem. J. 2017, 474, 1823–1836.

- Elmassry, M.M.; Zayed, A.; Farag, M.A. Gut homeostasis and microbiota under attack: Impact of the different types of food contaminants on gut health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 738–763.

- Wang, J.-Z.; Du, W.-T.; Xu, Y.-L.; Cheng, S.-Z.; Liu, Z.-J. Gut microbiome-based medical methodologies for early-stage disease prevention. Microb. Pathog. 2017, 105, 122–130.

- Melli, L.C.; do Carmo-Rodrigues, M.S.; Araújo-Filho, H.B.; Solé, D.; de Morais, M.B. Intestinal microbiota and allergic diseases: A systematic review. Allergol. Et Immunopathol. 2016, 44, 177–188.

- Damhorst, G.L.; Adelman, M.W.; Woodworth, M.H.; Kraft, C.S. Current Capabilities of Gut Microbiome–Based Diagnostics and the Promise of Clinical Application. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 223, S270–S275.

- Boertien, J.M.; Pereira, P.A.; Aho, V.T.; Scheperjans, F. Increasing comparability and utility of gut microbiome studies in Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review. J. Parkinsons Dis. 2019, 9, S297–S312.

- Wright, E.K.; Kamm, M.A.; Teo, S.M.; Inouye, M.; Wagner, J.; Kirkwood, C.D. Recent advances in characterizing the gastrointestinal microbiome in Crohn’s disease: A systematic review. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2015, 21, 1219–1228.

- Tang, W.W.; Wang, Z.; Kennedy, D.J.; Wu, Y.; Buffa, J.A.; Agatisa-Boyle, B.; Li, X.S.; Levison, B.S.; Hazen, S.L. Gut microbiota-dependent trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) pathway contributes to both development of renal insufficiency and mortality risk in chronic kidney disease. Circ. Res. 2015, 116, 448–455.

- Cénit, M.; Matzaraki, V.; Tigchelaar, E.; Zhernakova, A. Rapidly expanding knowledge on the role of the gut microbiome in health and disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2014, 1842, 1981–1992.

- Shkoporov, A.N.; Hill, C. Bacteriophages of the human gut: The “known unknown” of the microbiome. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 25, 195–209.

- Verma, D.; Garg, P.K.; Dubey, A.K. Insights into the human oral microbiome. Arch. Microbiol. 2018, 200, 525–540.

- Gomez, A.; Nelson, K.E. The oral microbiome of children: Development, disease, and implications beyond oral health. Microb. Ecol. 2017, 73, 492–503.

- Frame, L.A.; Costa, E.; Jackson, S.A. Current explorations of nutrition and the gut microbiome: A comprehensive evaluation of the review literature. Nutr. Rev. 2020, 78, 798–812.

- Chattopadhyay, I.; Verma, M.; Panda, M. Role of oral microbiome signatures in diagnosis and prognosis of oral cancer. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2019, 18, 1533033819867354.

- Aragon, I.M.; Herrera-Imbroda, B.; Queipo-Ortuño, M.I.; Castillo, E.; Del Moral, J.S.-G.; Gomez-Millan, J.; Yucel, G.; Lara, M.F. The urinary tract microbiome in health and disease. Eur. Urol. Focus 2018, 4, 128–138.

- Pascal, M.; Perez-Gordo, M.; Caballero, T.; Escribese, M.M.; Lopez Longo, M.N.; Luengo, O.; Manso, L.; Matheu, V.; Seoane, E.; Zamorano, M. Microbiome and allergic diseases. Front. immunol. 2018, 9, 1584.

- Lesko, L.J.; Atkinson Jr, A. Use of biomarkers and surrogate endpoints in drug development and regulatory decision making: Criteria, validation, strategies. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2001, 41, 347–366.

- Vostal, J.G.; Buehler, P.W.; Gelderman, M.P.; Alayash, A.I.; Doctor, A.; Zimring, J.C.; Glynn, S.A.; Hess, J.R.; Klein, H.; Acker, J.P. Proceedings of the Food and Drug Administration’s public workshop on new red blood cell product regulatory science 2016. Transfusion 2018, 58, 255–266.

- Hajjo, R.; Sabbah, D.A.; Bardaweel, S.K.; Tropsha, A. Identification of Tumor-Specific MRI Biomarkers Using Machine Learning (ML). Diagnostics 2021, 11, 742.

- Ling, Y.; Gong, T.; Zhang, J.; Gu, Q.; Gao, X.; Weng, X.; Liu, J.; Sun, J. Gut microbiome signatures are biomarkers for cognitive impairment in patients with ischemic stroke. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2020, 12, 297.

- Renz, H.; Brandtzaeg, P.; Hornef, M. The impact of perinatal immune development on mucosal homeostasis and chronic inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2011, 12, 9–23.

- Honda, K.; Littman, D.R. The microbiome in infectious disease and inflammation. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2012, 30, 759–795.

- Schuijs, M.J.; Willart, M.A.; Vergote, K.; Gras, D.; Deswarte, K.; Ege, M.J.; Madeira, F.B.; Beyaert, R.; van Loo, G.; Bracher, F.; et al. Farm dust and endotoxin protect against allergy through A20 induction in lung epithelial cells. Science 2015, 349, 1106–1110.

- Hofman, P.; Vouret-Craviari, V. Microbes-induced EMT at the crossroad of inflammation and cancer. Gut Microbes 2012, 3, 176–185.

- Miller, E.T.; Svanbäck, R.; Bohannan, B.J. Microbiomes as metacommunities: Understanding host-associated microbes through metacommunity ecology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2018, 33, 926–935.

- Adami, A.J.; Cervantes, J.L. The microbiome at the pulmonary alveolar niche and its role in Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Tuberculosis 2015, 95, 651–658.

- Bradlow, H.L. Obesity and the gut microbiome: Pathophysiological aspects. Horm. Mol. Biol. Clin. Investig. 2014, 17, 53–61.

- Drago, F.; Gariazzo, L.; Cioni, M.; Trave, I.; Parodi, A. The microbiome and its relevance in complex wounds. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2019, 29, 6–13.

- Salaspuro, M.P. Acetaldehyde, microbes, and cancer of the digestive tract. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2003, 40, 183–208.

- Khan, A.A.; Shrivastava, A.; Khurshid, M. Normal to cancer microbiome transformation and its implication in cancer diagnosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1826, 331–337.

- Kostic, A.D.; Xavier, R.J.; Gevers, D. The Microbiome in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Current Status and the Future Ahead. Gastroenterology 2014, 146, 1489–1499.

- Sears, C.L.; Garrett, W.S. Microbes, microbiota, and colon cancer. Cell Host Microbe 2014, 15, 317–328.

- Hullar, M.A.; Burnett-Hartman, A.N.; Lampe, J.W. Gut microbes, diet, and cancer. In Advances in Nutrition and Cancer; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 377–399.

- Whisner, C.M.; Aktipis, C.A. The role of the microbiome in cancer initiation and progression: How microbes and cancer cells utilize excess energy and promote one another’s growth. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2019, 8, 42–51.

- Half, E.; Keren, N.; Reshef, L.; Dorfman, T.; Lachter, I.; Kluger, Y.; Reshef, N.; Knobler, H.; Maor, Y.; Stein, A. Fecal microbiome signatures of pancreatic cancer patients. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 16801.

- Curty, G.; de Carvalho, P.S.; Soares, M.A. The role of the Cervicovaginal microbiome on the genesis and as a biomarker of premalignant cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and invasive cervical Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 222.

- Ridlon, J.M.; Wolf, P.G.; Gaskins, H.R. Taurocholic acid metabolism by gut microbes and colon cancer. Gut Microbes 2016, 7, 201–215.

- Puhr, M.; De Marzo, A.; Isaacs, W.; Lucia, M.S.; Sfanos, K.; Yegnasubramanian, S.; Culig, Z. Inflammation, microbiota, and prostate cancer. Eur. Urol. Focus 2016, 2, 374–382.

- Massari, F.; Mollica, V.; Di Nunno, V.; Gatto, L.; Santoni, M.; Scarpelli, M.; Cimadamore, A.; Lopez-Beltran, A.; Cheng, L.; Battelli, N. The human microbiota and prostate cancer: Friend or foe? Cancers 2019, 11, 459.

- Celardo, I.; Melino, G.; Amelio, I. Commensal microbes and p53 in cancer progression. Biol. Direct 2020, 15, 25.

- Azevedo, M.M.; Pina-Vaz, C.; Baltazar, F. Microbes and Cancer: Friends or Faux? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3115.

- Lérias, J.R.; Paraschoudi, G.; de Sousa, E.; Martins, J.; Condeço, C.; Figueiredo, N.; Carvalho, C.; Dodoo, E.; Castillo-Martin, M.; Beltrán, A. Microbes as master immunomodulators: Immunopathology, cancer and personalized immunotherapies. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 7, 362.

- Sawant, S.S.; Patil, S.M.; Gupta, V.; Kunda, N.K. Microbes as medicines: Harnessing the power of bacteria in advancing cancer treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7575.

- Guo, H.; Zhao, L.; Zhu, J.; Chen, P.; Wang, H.; Jiang, M.; Liu, X.; Sun, H.; Zhao, W.; Zheng, Z.; et al. Microbes in lung cancer initiation, treatment, and outcome: Boon or bane? Semin. Cancer Biol. 2021.

- Ammer-Herrmenau, C.; Pfisterer, N.; Weingarten, M.F.; Neesse, A. The microbiome in pancreatic diseases: Recent advances and future perspectives. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2020, 8, 878–885.

- De Martel, C.; Ferlay, J.; Franceschi, S.; Vignat, J.; Bray, F.; Forman, D.; Plummer, M. Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2008: A review and synthetic analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2012, 13, 607–615.

- Plummer, M.; de Martel, C.; Vignat, J.; Ferlay, J.; Bray, F.; Franceschi, S. Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2012: A synthetic analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 2016, 4, e609–e616.

- Temraz, S.; Nassar, F.; Nasr, R.; Charafeddine, M.; Mukherji, D.; Shamseddine, A. Gut microbiome: A promising biomarker for immunotherapy in colorectal cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4155.

- Jarman, R.; Ribeiro-Milograna, S.; Kalle, W. Potential of the microbiome as a biomarker for early diagnosis and prognosis of breast cancer. J. Breast Cancer 2020, 23, 579.

- Schwabe, R.F.; Jobin, C. The microbiome and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2013, 13, 800–812.

- Shahanavaj, K.; Gil-Bazo, I.; Castiglia, M.; Bronte, G.; Passiglia, F.; Carreca, A.P.; del Pozo, J.L.; Russo, A.; Peeters, M.; Rolfo, C. Cancer and the microbiome: Potential applications as new tumor biomarker. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2015, 15, 317–330.

- Lim, Y.; Totsika, M.; Morrison, M.; Punyadeera, C. Oral microbiome: A new biomarker reservoir for oral and oropharyngeal cancers. Theranostics 2017, 7, 4313.

- Rüb, A.M.; Tsakmaklis, A.; Gräfe, S.K.; Simon, M.-C.; Vehreschild, M.J.G.T.; Wuethrich, I. Biomarkers of human gut microbiota diversity and dysbiosis. Biomark. Med. 2021, 15, 139–150.

- Ananthakrishnan, A.N. Microbiome-based biomarkers for IBD. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2020, 26, 1463–1469.

- Lin, H.; He, Q.-Y.; Shi, L.; Sleeman, M.; Baker, M.S.; Nice, E.C. Proteomics and the microbiome: Pitfalls and potential. Expert Rev. Proteomics 2019, 16, 501–511.

- Marcos-Zambrano, L.J.; Karaduzovic-Hadziabdic, K.; Loncar Turukalo, T.; Przymus, P.; Trajkovik, V.; Aasmets, O.; Berland, M.; Gruca, A.; Hasic, J.; Hron, K. Applications of machine learning in human microbiome studies: A review on feature selection, biomarker identification, disease prediction and treatment. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 313.

- Kang, C.Y.; Duarte, S.E.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, E.; Park, J.; Lee, A.D.; Kim, Y.; Kim, L.; Cho, S.; Oh, Y.; et al. Artificial Intelligence-based Radiomics in the Era of Immuno-oncology. Oncologist 2022, 27, e471–e483.

- Zhou, Z.; Ge, S.; Li, Y.; Ma, W.; Liu, Y.; Hu, S.; Zhang, R.; Ma, Y.; Du, K.; Syed, A.; et al. Human Gut Microbiome-Based Knowledgebase as a Biomarker Screening Tool to Improve the Predicted Probability for Colorectal Cancer. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 596027.

- Marech, I.; Ammendola, M.; Gadaleta, C.; Zizzo, N.; Oakley, C.; Gadaleta, C.D.; Ranieri, G. Possible biological and translational significance of mast cells density in colorectal cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 8910–8920.

- Mao, Y.; Feng, Q.; Zheng, P.; Yang, L.; Zhu, D.; Chang, W.; Ji, M.; He, G.; Xu, J. Low tumor infiltrating mast cell density confers prognostic benefit and reflects immunoactivation in colorectal cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2018, 143, 2271–2280.

- Sammarco, G.; Gallo, G.; Vescio, G.; Picciariello, A.; De Paola, G.; Trompetto, M.; Currò, G.; Ammendola, M. Mast Cells, microRNAs and Others: The Role of Translational Research on Colorectal Cancer in the Forthcoming Era of Precision Medicine. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2852.

- Groll, T.; Silva, M.; Sarker, R.S.J.; Tschurtschenthaler, M.; Schnalzger, T.; Mogler, C.; Denk, D.; Schölch, S.; Schraml, B.U.; Ruland, J.; et al. Comparative Study of the Role of Interepithelial Mucosal Mast Cells in the Context of Intestinal Adenoma-Carcinoma Progression. Cancers 2022, 14, 2248.

- Pellino, G.; Gallo, G.; Pallante, P.; Capasso, R.; De Stefano, A.; Maretto, I.; Malapelle, U.; Qiu, S.; Nikolaou, S.; Barina, A.; et al. Noninvasive Biomarkers of Colorectal Cancer: Role in Diagnosis and Personalised Treatment Perspectives. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2018, 2018, 2397863.

- Ghareib, A.F.; Mohamed, R.H.; Abd El-Fatah, A.R.; Saadawy, S.F. Assessment of Serum MicroRNA-21 Gene Expression for Diagnosis and Prognosis of Colorectal Cancer. J. Gastrointest. Cancer 2020, 51, 818–823.

- Tarallo, S.; Ferrero, G.; Gallo, G.; Francavilla, A.; Clerico, G.; Realis Luc, A.; Manghi, P.; Thomas, A.M.; Vineis, P.; Segata, N.; et al. Altered Fecal Small RNA Profiles in Colorectal Cancer Reflect Gut Microbiome Composition in Stool Samples. mSystems 2019, 4, e00289-19.

- Thomas, S.; Izard, J.; Walsh, E.; Batich, K.; Chongsathidkiet, P.; Clarke, G.; Sela, D.A.; Muller, A.J.; Mullin, J.M.; Albert, K. The host microbiome regulates and maintains human health: A primer and perspective for non-microbiologists. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 1783–1812.

- Thomas-White, K.; Brady, M.; Wolfe, A.J.; Mueller, E.R. The bladder is not sterile: History and current discoveries on the urinary microbiome. Curr. Bladder Dysfunct. Rep. 2016, 11, 18–24.

- Zhang, D.; Chen, G.; Manwani, D.; Mortha, A.; Xu, C.; Faith, J.J.; Burk, R.D.; Kunisaki, Y.; Jang, J.E.; Scheiermann, C.; et al. Neutrophil ageing is regulated by the microbiome. Nature 2015, 525, 528–532.

- Xu, C.; Lee, S.K.; Zhang, D.; Frenette, P.S. The Gut Microbiome Regulates Psychological-Stress-Induced Inflammation. Immunity 2020, 53, 417–428 e414.

- Rojo, D.; Méndez-García, C.; Raczkowska, B.A.; Bargiela, R.; Moya, A.; Ferrer, M.; Barbas, C. Exploring the human microbiome from multiple perspectives: Factors altering its composition and function. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 41, 453–478.

- Cingi, C.; Muluk, N.B.; Scadding, G.K. Will every child have allergic rhinitis soon? Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2019, 118, 53–58.

- Aldars-García, L.; Chaparro, M.; Gisbert, J.P. Systematic Review: The Gut Microbiome and Its Potential Clinical Application in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 977.

- Caussy, C.; Loomba, R. Gut microbiome, microbial metabolites and the development of NAFLD. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 15, 719–720.

- Ipci, K.; Altıntoprak, N.; Muluk, N.B.; Senturk, M.; Cingi, C. The possible mechanisms of the human microbiome in allergic diseases. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2017, 274, 617–626.

- Hoffmann, C.; Dollive, S.; Grunberg, S.; Chen, J.; Li, H.; Wu, G.D.; Lewis, J.D.; Bushman, F.D. Archaea and fungi of the human gut microbiome: Correlations with diet and bacterial residents. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66019.

- Saraswati, S.; Sitaraman, R. Aging and the human gut microbiota—from correlation to causality. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 5, 764.

- Goodrich, J.K.; Davenport, E.R.; Waters, J.L.; Clark, A.G.; Ley, R.E. Cross-species comparisons of host genetic associations with the microbiome. Science 2016, 352, 532–535.

- Markowiak, P.; Śliżewska, K. The role of probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics in animal nutrition. Gut Pathog. 2018, 10, 21.

- Manrique, P.; Bolduc, B.; Walk, S.T.; van der Oost, J.; de Vos, W.M.; Young, M.J. Healthy human gut phageome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 10400–10405.

- Parfrey, L.W.; Walters, W.A.; Lauber, C.L.; Clemente, J.C.; Berg-Lyons, D.; Teiling, C.; Kodira, C.; Mohiuddin, M.; Brunelle, J.; Driscoll, M. Communities of microbial eukaryotes in the mammalian gut within the context of environmental eukaryotic diversity. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 298.

- LeBlanc, J.G.; Milani, C.; De Giori, G.S.; Sesma, F.; Van Sinderen, D.; Ventura, M. Bacteria as vitamin suppliers to their host: A gut microbiota perspective. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2013, 24, 160–168.

- Rowland, I.; Gibson, G.; Heinken, A.; Scott, K.; Swann, J.; Thiele, I.; Tuohy, K. Gut microbiota functions: Metabolism of nutrients and other food components. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 57, 1–24.

- Steinert, R.E.; Lee, Y.-K.; Sybesma, W. Vitamins for the gut microbiome. Trends Mol. Med. 2020, 26, 137–140.

More