According to the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO), vaginal cancer is strictly defined as cancer found in the vagina without clinical or histologic evidence of cervical or vulvar cancer, or a prior history of these cancers within 5 years. Primary vaginal cancer is a rare gynecologic malignancy. Given the rarity of the disease, standardized approaches to management are limited, and a great variety of therapeutic conditions are endorsed.

- vaginal carcinoma

- vaginal tumors

- vaginal cancers

- human papilloma virus

- surgery

- external beam radiation

- brachytherapy

- concurrent chemoradiation

- immunotherapy

1. Epidemiology and Risk Factors

2. Anatomy

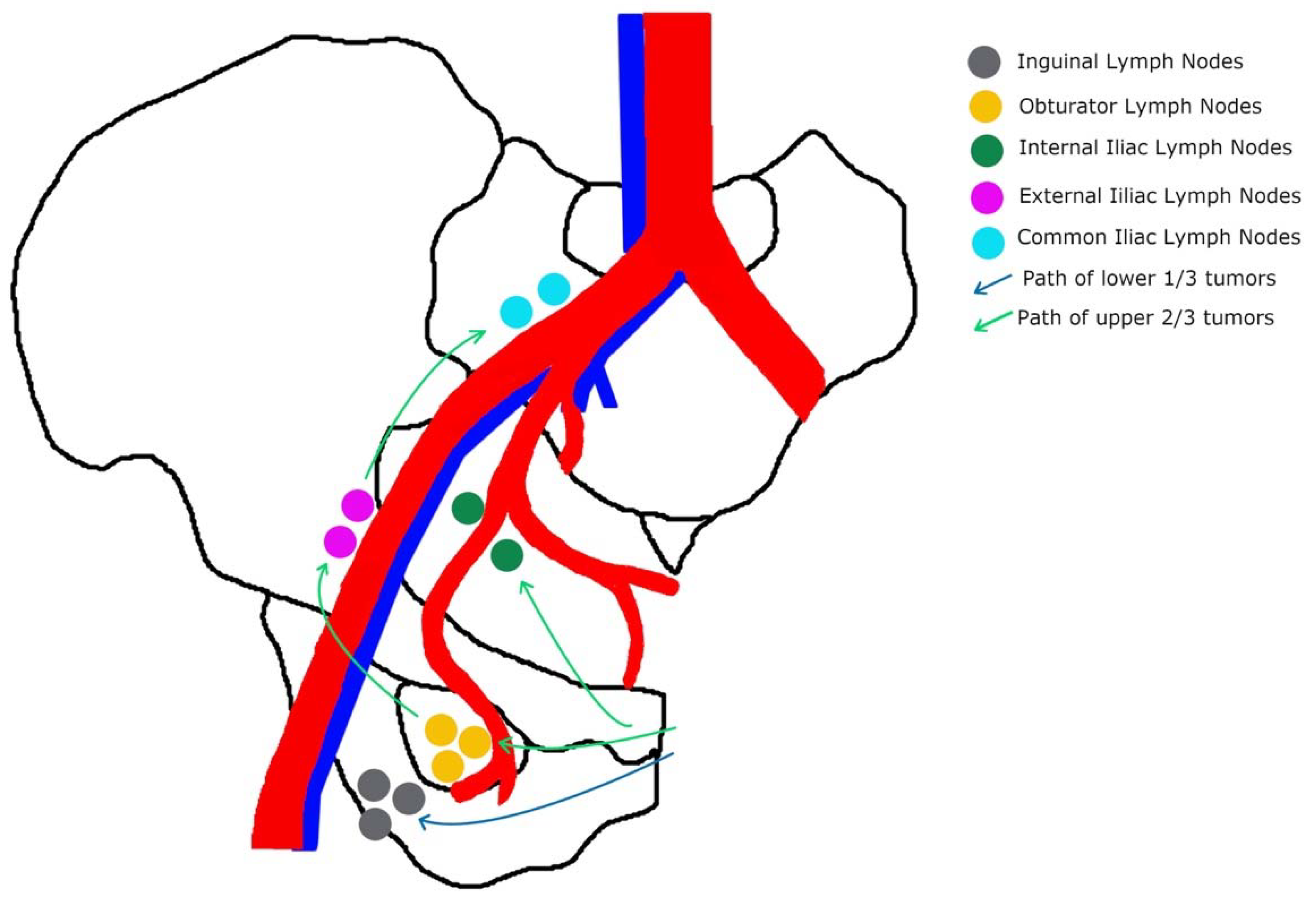

The most common site for vaginal cancer is the vaginal apex or upper third of the vagina, which accounts for 56 percent of cases [1,10]. Subsequently, the lower third of the vagina accounts for 31 percent of cases, and lastly, the middle third accounts for 13 percent [10]. Figure 1 outlines the lymphatic drainage of vaginal cancer. Tumors localized in the upper two-thirds of the vagina most likely drain into the pelvic lymph nodes, including the obturator, internal iliac, and external iliac; while tumors in the lower third drain into the inguinal lymph nodes [9,10]. Lesions in the mid-vagina may follow both the pelvic and groin routes [9]. In addition to lymphatic spread, vaginal cancer also spreads directly to para-cervical tissues, to the vulva, and by contiguity to the bladder and rectum [11]. Hematogenous spread to the lung, liver, and bone is also seen in late manifestations [1]. Thus, the route of metastasis varies with site and extension of the primary tumor.

3. Prognostic Factors

4. Diagnosis and Staging

There are no routine screening programs for vaginal cancer. However, Pap smears are effective in detecting asymptomatic lesions. In cases of abnormal results without gross cervical lesions, a colposcopy of the vagina should be performed. Painless vaginal bleeding and vaginal discharge, as well as post-coital or postmenopausal bleeding, are common signs of vaginal cancer [3,11]. There may be involvement or compression of nearby organs resulting in urinary complaints such as retention, dysuria, hematuria, or gastrointestinal symptoms such as tenesmus, constipation, or melena. Locally advanced disease is also associated with pelvic pain. Approximately 5 to 10% of women remain asymptomatic and disease is detected during routine physical examination or following an abnormal Pap test [3]. A biopsy will confirm a diagnosis. A thorough physical examination is an essential component for the evaluation of the local extent of the disease. Specifically, noting the location, gross morphology, sites of involvement, and dimensions of the visible and palpable tumor will be important for the management of the disease [3]. Visualization of the entire vagina can be performed under general anesthesia if needed. Staging is performed clinically rather than surgically; it is based on the FIGO staging system. Stage I disease is limited to the vaginal wall. Stage II disease involves subvaginal tissue, but it does not extend to the pelvic wall. Stage III tumor extends to the pelvic wall, and Stage IV tumor extends beyond the true pelvis or involves the mucosa of the bladder or rectum. With imaging not incorporated into the FIGO staging system, the extent of disease in each stage can be variable. Due to this, FIGO recommends that where available, imaging findings guide management [1]. As reviportewed by Jhingran, MRI is recommended for assessment of tumor volume, extension of disease, and recurrence and complications [9]. As extrapolated from cervical cancer data, MRI is more sensitive in detecting tumor size, and paravaginal or parametrial involvement [1]. PET/CT is also superior to other modalities for assessing lymph nodes and detecting recurrence [1,9].5. Management

Surgical Management

In the treatment of vaginal cancer, surgery has a limited role given the proximity of the vagina to vital organs such as the bladder, urethra, and rectum. As such, surgery is considered in selected cases of: (1) small stage I and II tumors that are confined to the upper posterior vagina; (2) stage IV disease with recto-vaginal or vesico-vaginal fistulas; and (3) central recurrence after RT [1,11].

Surgical resections for vaginal cancer include local tumor excision (LTE), vaginectomy (partial, total, and radical), and pelvic exenteration. The type of surgery depends on the location and extent of the initial tumor. Zhou et al. recently compared the effectiveness of LTE versus vaginectomy for stage I and stage II vaginal carcinoma using SEER data from 2004 to 2016. Although LTE is more commonly performed over vaginectomy as a less aggressive procedure and to preserve sexual function, vaginectomy resulted in significantly prolonged survival and should be the preferred treatment regardless of radiotherapy status [12].

Radiation Therapy

Definitive RT based on external beam (EBRT) and/or brachytherapy (BT) is considered a standard approach to treatment for vaginal cancer, especially for locally advanced cases. There are no prospective trials on the role of RT for primary vaginal cancer [1,9,29,30].

Yang et al. performed a retrospapective reviewr of 124 patients at their institution treated for primary vaginal cancer [30]. Of these, a total of 86 patients underwent primary EBRT with a dose ranging from 45 to 66 Gy. For patients who are stage I–II, overall survival outcomes with primary surgery are comparable to primary RT [30].

Chemoradiation Therapy

Due to the similarities in the histology, HPV association, and natural history of cervical cancer and vaginal cancer, treatment decisions for vaginal cancer often extrapolate from evidence for cervical cancer. CCRT has been increasing in use for the treatment of vaginal cancer, mirroring the rates for the treatment of cervical cancer [35,36]. Various retrospective studies have demonstrated a potential benefit of the use of CCRT for vaginal cancer. The most common agents used are cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil. While the impact on OS varies among the studies, they overall demonstrate that CCRT is well-tolerated by patients, with minimal grade 3–4 toxicities seen [36,37,38,39]. Systemic Treatments Due to the rarity of vaginal cancer, and even more so, the rarity of advanced vaginal cancer, prospective data and clinical trial data on the efficacy of systemic treatments are sparse. One phase II trial on the use of cisplatin in recurrent or metastatic vaginal cancer included 22 patients with various histologies [42]. An overall response rate of 6.25% was demonstrated in the 16 patients with squamous histology. The role of immunotherapy is of interest, particularly for HPV-related cancers such as vaginal cancer. Due to the rarity of the disease, patients with vaginal cancer are often grouped together with vulvar cancer in clinical trials. One phase II basket trial on the use of pembrolizumab, a PD-1 inhibitor, in the treatment of recurrent or metastatic disease included two patients with vaginal cancer. Both patients demonstrated recurrent disease with distant metastases and had been previously treated with radiation and multiple lines of chemotherapy. One patient demonstrated stable disease in response, while the second had progression on treatment. Treatment with pembrolizumab was well-tolerated, with grade 2 fatigue as the only treatment-related adverse event reported [43].