Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Jason Zhu and Version 1 by Réka Saáry.

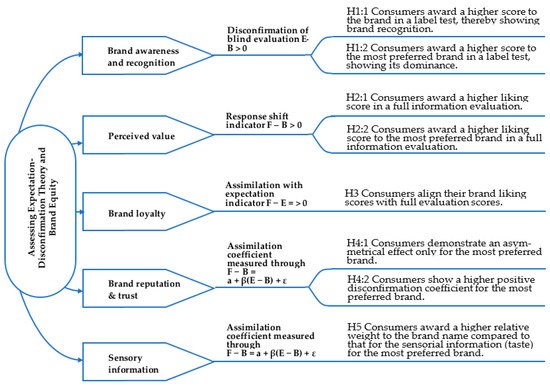

Combining brand equity indicators with Expectation–Disconfirmation Theory (EDT) provides insight into the hardly measurable influential variables of brand loyalty and brand equity evaluation. The results suggest that the satisfaction level (i.e., product evaluation) can be explained in more depth by the divided response shift indicator in the case of a familiar, low involvement product such as mineral water. It can be stated that the positive and negative disconfirmations of the response shift, which measures the weight of a brand in the overall evaluation of a product, can provide accurate information for brand managers.

- Expectation–Disconfirmation Theory (EDT)

- brand equity

- brand management

1. Introduction

Safety incidents in the food system have a deleterious effect on consumer trust [1]. Consumer trust is an essential aspect in the functioning of any market but mainly in the food and drinks sector [2]. Food scandals, such as the bovine spongiform encephalopathy outbreak in the 1990s, the ‘horsemeat scandal’ in 2013, dioxins in food in Belgium in 1999, and the detection of mad cow disease in Britain affect consumers’ trust [3]. In addition to food incidents, increased sophistication and globalization of food markets are accompanied by the distancing of the consumer from the production source. Similarly, this augmented complexity and distance have contributed to a decline in trust and simultaneously increased the importance of trust.

This is a challenging issue in developing countries such as Albania, where consumers lack trust in institutions, especially those linked to regulatory systems related to food [4]. Trust is essential in individuals’ food purchasing decisions and understanding the factors that stimulate and mitigate consumers’ trust in food, to inform the public and business sector, is necessary for both developed and developing countries. The trust concept is analyzed mainly in social sciences because of its substantial relationship with development in general and socioeconomic development in particular [5,6][5][6]. No single consensual definition is agreed on trust, and several nuances persist in the academic debate [7,8][7][8]. However, trust is essential for cooperative behavior and solving collective action problems [9]. In addition, rational choice scholars implicitly or explicitly equate trust with simple institution-induced expectations [10]. Similarly, in the entrepreneurial context, a firm owner expects a business partner to act in their interest or take such interests into account, which is also an expectation issue [8].

According to the paper reviewsearch of consumers and trust, Hobbs and Goddard [7] mention four broad categories of trust as follows: (1) institutional trust (trust in regulatory systems), (2) generalized trust (measured through the general trust that people have in others), (3) calculative trust (individuals behaving in such a way that does not cause harm for their interest, and (4) finally relational trust that derives from the cumulative experience between the trustee and trustor. The last one derives from familiarity and experience [11,12][11][12]. The four mentioned categories of trust had been analyzed in the food context, showing an impact on specific consumer decisions. Ding and hires co-authoearchers [13] analyze the relationship between generalized trust and consumer behavior, showing that in the case of health-risk related functional food, trusting people are more likely to buy them. Although in the case of the environmental footprint related to food, generalized trust does not impact German consumer choices [14]. Peters et al. [15] also show that institutional trust impacts attitudes toward biotechnology in USA consumers and not in German ones. Similarly, Siegrist and Hartmann [16] show that trust in the food industry directly influences the acceptance of cultured meat. Consumers who trust the food industry are more likely to buy functional foods than consumers who do not [17].

Consequently, trust has an influence on customer choice and perceived quality, and therefore, on customer satisfaction [18]. Other studies show the interrelationship between trust and consumer risk perceptions in food choices; Janssen and Hamm [19] point out that German consumers show low trust in the European Union (EU) mandatory logo on organic products vs. German logos. In comparison, Albanian consumers show the contrary [4]. When dealing with consumer and trust issues, researchers have reiterated the importance of institutional trust by jointly merging public with private activities. Indeed, the lack of trust in public institutions in the food industry erodes consumer confidence even in private institutions [20]. In this framework, brands represent private institutions that might reduce the risks in food choices induced by the lack of trust in public institutions. In the definition of Lin and Nugent [21] (p. 2037), institutions are defined as “a set of humanly devised behavioral rules that govern and shape the interactions of human beings, in part by helping them to form expectations of what other people will do”. In this vein, brand processes and activities shape human interactions around a product and service and generate expectations.

Consequently, strong brands can mitigate the effect of low trust in institutions and consumer decisions [22]. Origin bounded brands (OBBs) can mitigate through reputation the negative effect of low trust in institutions [23,24,25][23][24][25]. However, whether in people, organizations or marketing constructs such as brand, trust is not an immutable attitude, and most changes in it are in a negative direction due to the greater salience of negative information [26]. Thus, monitoring the trust levels in public or private companies is particularly relevant nowadays, given the amount of information that the individual has to process daily. In that regard, customer-based brand evaluation processes from a trust perspective play a pivotal role.

2. Expectation–Disconfirmation Theory

In markets where products and services have become similar, with no significant functional differences and consumer choices are more and more influenced by emotional aspects rather than rational thinking, experiences have surfaced as the primary form of differentiation [1]. Marketing academics and practitioners have acknowledged that consumers look for brands that provide them with unique and memorable experiences [2]. In this vein, from the consumer viewpoint, brands are relationship builders, and the sensory information that they convey affects satisfaction, trust and loyalty [2]. The sensory perception of consumers has explicit and implicit impacts on brand evaluation. Haas and her co-mauthortes show that the implicit factors have a notable effect on explicit characteristics and brand experience and do not contradict each other [22]. In the same vein, non-physical, intangible factors can affect consumer sensory perceptions. Consequently, the customer believes more in the brand than the objective features in the absence of information. Many studies view brand trust as central and conceptualize it as a notable factor in the firm’s success [27]. Brand trust is viewed as a long process that can occur by considering consumer experiences. Therefore, brand trust can be discussed as a cognitive component that may induce an emotional response and expectations [28]. Several reseauthorchers have analyzed the impact of product credence attributes such as brand, advertisement, packaging, label, price and origin on sensorial expectations [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40]. The application of neuromarketing tools is also a common procedure in thise research field [41,42][41][42]; however, the reliability of these methods is not yet widely accepted [43]. Scholars, as mentioned earlier, have used Expectation–Disconfirmation Theory (EDT) to assess the influence of credence attributes on the consumer evaluations of several food products. However, to the authors’ knowledge, this theory was not used previously to measure trust based on brand expectations. Disconfirmation of expectancies refers to the difference between expectations and objective quality, or in other words, the real performance of a product [29,30,44,45,46,47][29][30][44][45][46][47]. According to Lee and his co-mauthortes [48], expectations create the baseline for satisfaction—if disconfirmation occurs, customer satisfaction will be higher or lower than the baseline level. Disconfirmation is positive when product performance exceeds expectations and vice versa [45]. In addition, disconfirmation can be asymmetrical when positive and negative disconfirmations are not of the same size. Thus, analyzing the brand’s perceived quality and expectations, its strength from a consumer perspective and the level of trust the latter confers to them can be evaluated. When consumers taste a food product, their perception is often biased by preconceived ideas in product evaluation. Schifferstein [44] identifies a set of three alternative ways to isolate sensory from non-sensory preferences: (1) blind testing with a product, which provides experience attribute information; (2) expectation testing (E), which permits the collection of credence (accumulated trust) attribute information; and (3) full information testing (involving the provision to the consumer of experience and credence information regarding the product). The differences between the scores measured using these three tests can be used to measure BE and the trust score for the specific brand from the consumer perspective.Full information test score (F) − Expectation score (E) = Degree of Disconfirmation

Expectation test score (E) − Blind test score (B) = Degree of Incongruence (reputation)

Full information test score (F) − Blind test score (B) = Degree of Response shift (trust on brand information)

Figure 1. Mapping brand equity with Expectation–Disconfirmation Theory. Note: Expectation score (E); Blind test score (B); Full information test score (F); B1, B2, B3, B4: conducted brands; α: Level of assimilation (proportion of the response shift over the degree of incongruence); β, ε: function coefficients. Source: Authors’ construction.

References

- Wu, W.; Zhang, A.; van Klinken, R.D.; Schrobback, P.; Muller, J.M. Consumer Trust in Food and the Food System: A Critical Review. Foods 2021, 10, 2490.

- Benson, T.; Lavelle, F.; Spence, M.; Elliott, C.T.; Dean, M. The Development and Validation of a Toolkit to Measure Consumer Trust in Food. Food Control 2020, 110, 106988.

- Berg, L. Trust in Food in the Age of Mad Cow Disease: A Comparative Study of Consumers’ Evaluation of Food Safety in Belgium, Britain and Norway. Appetite 2004, 42, 21–32.

- Kokthi, E.; Limon, M.G.; Vazquez Bermudez, I. Origin or Food Safety Attributes? Analyzing Consumer Preferences Using Likert Scale. New Medit 2015, 14, 50–58.

- Baskakova, I. Trust as a Factor in the Development of the Economy in the Context of Digitalization. KnE Soc. Sci. 2021, 5, 391–398.

- Yuan, Z.; Wang, L. Trust and Economic Development: A Literature Review. J. Lanzhou Univ. Financ. Econ. 2019, 35, 1.

- Hobbs, J.E.; Goddard, E. Consumers and Trust. Food Policy 2015, 52, 71–74.

- Welter, F. All We Need Is Trust?A Critical Review of the Trust and Entrepreneurship Literature. Int. Small Bus. J. 2012, 30, 193–212.

- Rothstein, B. Social Traps and the Problem of Trust, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005; ISBN 978-0-521-84829-9.

- Kelling, N.K.; Sauer, P.C.; Gold, S.; Seuring, S. The Role of Institutional Uncertainty for Social Sustainability of Companies and Supply Chains. J. Bus. Ethics. 2021, 173, 813–833.

- Schoder, D.; Haenlein, M. The Relative Importance of Different Trust Constructs for Sellers in the Online World. Electron. Mark. 2004, 14, 48–57.

- Barijan, D.; Ariningsih, E.P.; Rahmawati, F. The Influence of Brand Trust, Brand Familiarity, and Brand Experience on Brand Attachments. J. Digit. Mark. Halal Ind. 2021, 3, 73–84.

- Ding, Y.; Veeman, M.M.; Adamowicz, W.L. Functional Food Choices: Impacts of Trust and Health Control Beliefs on Canadian Consumers’ Choices of Canola Oil. Food Policy 2015, 52, 92–98.

- Grebitus, C.; Steiner, B.; Veeman, M. The Roles of Human Values and Generalized Trust on Stated Preferences When Food Is Labeled with Environmental Footprints: Insights from Germany. Food Policy 2015, 52, 84–91.

- Peters, H.P.; Lang, J.T.; Sawicka, M.; Hallman, W.K. Culture and Technological Innovation: Impact of Institutional Trust and Appreciation of Nature on Attitudes towards Food Biotechnology in the USA and Germany. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 2007, 19, 191–220.

- Siegrist, M.; Hartmann, C. Perceived Naturalness, Disgust, Trust and Food Neophobia as Predictors of Cultured Meat Acceptance in Ten Countries. Appetite 2020, 155, 104814.

- Siegrist, M.; Stampfli, N.; Kastenholz, H. Consumers’ Willingness to Buy Functional Foods. The Influence of Carrier, Benefit and Trust. Appetite 2008, 51, 526–529.

- Uzir, M.U.H.; Al Halbusi, H.; Thurasamy, R.; Thiam Hock, R.L.; Aljaberi, M.A.; Hasan, N.; Hamid, M. The Effects of Service Quality, Perceived Value and Trust in Home Delivery Service Personnel on Customer Satisfaction: Evidence from a Developing Country. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 63, 102721.

- Janssen, M.; Hamm, U. Product Labelling in the Market for Organic Food: Consumer Preferences and Willingness-to-Pay for Different Organic Certification Logos. Food Qual. Prefer. 2012, 25, 9–22.

- Liu, R.; Pieniak, Z.; Verbeke, W. Food-Related Hazards in China: Consumers’ Perceptions of Risk and Trust in Information Sources. Food Control 2014, 46, 291–298.

- Lin, J.; Nugent, J.B. Chapter 38 Institutions and Economic Development. In Handbook of Development Economics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1995; pp. 2303–2370.

- Petrovskaya, I.; Haleem, F. Socially Responsible Consumption in Russia: Testing the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Moderating Role of Trust. Bus. Ethics Environ. Amp. Responsib. 2021, 30, 38–53.

- Kokthi, E.; Guri, G.; Muco, E. Assessing the Applicability of Geographical Indications from the Social Capital Analysis Perspective: Evidences from Albania. Econ. Sociol. 2021, 14, 32–53.

- Kokthi, E.; Muço, E.; Requier-Desjardins, M.; Guri, F. Social Capital as a Determinant for Raising Ecosystem Services Awareness—An Application to an Albanian Pastoral Ecosystem. Landsc. Online 2021, 95, 1–17.

- Kokthi, E.; Kruja, D. Customer Based Brand Equity Analysis: An Empirical Analysis to Geographical Origin. In Management, Enterprise and Benchmarking in the 21st Century; Óbuda University Keleti Károly Faculty of Economics: Budapest, Hungary, 2017; p. 171.

- Greenberg, M.R. Energy Policy and Research: The Underappreciation of Trust. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2014, 1, 152–160.

- Akoglu, H.E.; Özbek, O. The Effect of Brand Experiences on Brand Loyalty through Perceived Quality and Brand Trust: A Study on Sports Consumers. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2021; Epub ahead of printing.

- Eshuis, J.; Geest, T.; Klijn, E.H.; Voets, J.; Florek, M.; George, B. The Effect of the EU—Brand on Citizens’ Trust in Policies: Replicating an Experiment. Public Admin. Rev. 2021, 81, 776–786.

- Deliza, R.; MacFie, H.J.H. The Generation of Sensory Expectation by External Cues and Its Effect on Sensory Perception and Hedonic Ratings: A Review. J. Sens. Stud. 1996, 11, 103–128.

- d’Hauteville, F.; Fornerino, M.; Philippe Perrouty, J. Disconfirmation of Taste as a Measure of Region of Origin Equity: An Experimental Study on Five French Wine Regions. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2007, 19, 33–48.

- Schifferstein, H.N.J.; Kole, A.P.W.; Mojet, J. Asymmetry in the Disconfirmation of Expectations for Natural Yogurt. Appetite 1999, 32, 307–329.

- Siret, F.; Issanchou, S. Traditional Process: Influence on Sensory Properties and on Consumers’ Expectation and Liking Application to ‘pâté de Campagne. Food Qual. Prefer. 2000, 11, 217–228.

- Lange, C.; Martin, C.; Chabanet, C.; Combris, P.; Issanchou, S. Impact of the Information Provided to Consumers on Their Willingness to Pay for Champagne: Comparison with Hedonic Scores. Food Qual. Prefer. 2002, 13, 597–608.

- Jo, J.; Lusk, J.L. If It’s Healthy, It’s Tasty and Expensive: Effects of Nutritional Labels on Price and Taste Expectations. Food Qual. Prefer. 2018, 68, 332–341.

- Carvalho, F.M.; Spence, C. Cup Colour Influences Consumers’ Expectations and Experience on Tasting Specialty Coffee. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 75, 157–169.

- Haasova, S.; Florack, A. Sugar Labeling: How Numerical Information of Sugar Content Influences Healthiness and Tastiness Expectations. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223510.

- Stefani, G.; Romano, D.; Cavicchi, A. Consumer Expectations, Liking and Willingness to Pay for Specialty Foods: Do Sensory Characteristics Tell the Whole Story? Food Qual. Prefer. 2006, 17, 53–62.

- Kokthi, E.; Kruja, D. Consumer Expectations for Geographical Origin: Eliciting Willingness to Pay (WTP) Using the Disconfirmation of Expectation Theory (EDT). J. Food Prod. Mark. 2017, 23, 873–889.

- Kokthi, E.; Kelemen-Erdos, A. Assimilation-Contrast Theory: Support for the Effect of Brand in Consumer Preferences. In FIKUSZ’17 Proceedings; Fodor, M., Fehér-Polgár, P., Eds.; Óbuda University: Budapest, Hungary, 2017; pp. 157–168. ISBN 978-963-449-064-7.

- Peбзyeв, Б.Г. Poль Boвлeчeннocти Пpи Boзникнoвeнии Accимиляции/Koнтpacтa в Oцeнкax Пoтpeбитeльcкoй Удoвлeтвopeннocти. Psychology 2021, 18, 506–524.

- McClure, S.M.; Li, J.; Tomlin, D.; Cypert, K.S.; Montague, L.M.; Montague, P.R. Neural Correlates of Behavioral Preference for Culturally Familiar Drinks. Neuron 2004, 44, 379–387.

- de Wijk, R.A.; Ushiama, S.; Ummels, M.; Zimmerman, P.; Kaneko, D.; Vingerhoeds, M.H. Reading Food Experiences from the Face: Effects of Familiarity and Branding of Soy Sauce on Facial Expressions and Video-Based RPPG Heart Rate. Foods 2021, 10, 1345.

- Moya, I.; García-Madariaga, J.; Blasco, M.-F. What Can Neuromarketing Tell Us about Food Packaging? Foods 2020, 9, 1856.

- Schifferstein, H.N.J. Effects of Product Beliefs on Product Perception and Liking. In Food, People and Society; Frewer, L.J., Risvik, E., Schifferstein, H.N.J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; pp. 73–96. ISBN 978-3-642-07477-6.

- Oliver, R.L. A Cognitive Model of the Antecedents and Consequences of Satisfaction Decisions. J. Mark. Res. 1980, 17, 460–469.

- Wang, X.; Zhou, R.; Zhang, R. The Impact of Expectation and Disconfirmation on User Experience and Behavior Intention. In Proceedings of the DUXU: 9th International Conference Design, User Experience, and Usability, Copenhagen, Denmark, 19–24 July 2020; Marcus, A., Rosenzweig, E., Eds.; Part I. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020.

- Cai, R.; Chi, C.G.-Q. Pictures vs. Reality: Roles of Disconfirmation Magnitude, Disconfirmation Sensitivity, and Branding. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 98, 103040.

- Lee, Y.-J.; Kim, I.-A.; van Hout, D.; Lee, H.-S. Investigating Effects of Cognitively Evoked Situational Context on Consumer Expectations and Subsequent Consumer Satisfaction and Sensory Evaluation. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 94, 104330.

- Fornerino, M.; d’Hauteville, F. How Good Does It Taste? Is It the Product or the Brand? A Contribution to Brand Equity Evaluation. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2010, 19, 34–43.

- Anderson, R. Consumer Dissatisfaction the Effect of Disconfirmed Expectancy on Perceived Product Performance. J. Mark. Res. 1973, 10, 38–44.

- Anderson, E.W.; Sullivan, M.W. The Antecedents and Consequences of Customer Satisfaction for Firms. Mark. Sci. 1993, 12, 125–143.

- Hoch, S.J.; Ha, Y.-W. Consumer Learning: Advertising and the Ambiguity of Product Experience. J. Consum. Res. 1986, 13, 221–233.

- Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Lin, X.; Abdullat, A. The Dual Concept of Consumer Value in Social Media Brand Community: A Trust Transfer Perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 59, 102319.

- Aaker, D.A. Managing Brand Equity; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991.

- Keller, K.L. Building Strong Brands in a Modern Marketing Communications Environment. J. Mark. Commun. 2009, 15, 139–155.

- Farhana, M. Brand Elements Lead to Brand Equity: Differentiate or Die. Inf. Manag. Bus. Rev. 2012, 4, 223–233.

- Keller, K.L. Brand Synthesis: The Multidimensionality of Brand Knowledge. J Consum. Res. 2003, 29, 595–600.

- Gunasti, K.; Kara, S.; Ross, W.T., Jr. Effects of Search, Experience and Credence Attributes versus Suggestive Brand Names on Product Evaluations. Eur. J. Mark. 2020, 54.

- Huang, R.; Sarigöllü, E. How Brand Awareness Relates to Market Outcome, Brand Equity, and the Marketing Mix. In Fashion Branding and Consumer Behaviors; Choi, T.-M., Ed.; International Series on Consumer Science; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 113–132. ISBN 978-1-4939-0276-7.

- Dressler, M.; Paunovic, I. The Value of Cons istency: Portfolio Labeling Strategies and Impact on Winery Brand Equity. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1400.

- Aaker, D.A. Measuring Brand Equity Across Products and Markets. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1996, 38, 102–120.

- Csiszárik-Kocsir, Á.; Garai-Fodor, M.; Varga, J. What Has Become Important during the Pandemic?—Reassessing Preferences and Purchasing Habits as an Aftermath of the Coronavirus Epidemic through the Eyes of Different Generations. Acta Polytech. Hung. 2021, 18, 49–74.

- Jacoby, J.; Olson, J.C. (Eds.) Perceived Quality: How Consumers View Stores and Merchandise; The Advances in Retailing Series; LexingtonBooks: Lexington, KY, USA, 1985; ISBN 978-0-669-08272-2.

- Schifferstein, H. Effects of Products Beliefs on Product Perception and Liking. In Food, People and Society A Europian Perspective of Consumer Choices; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; pp. 73–96.

More