Gastrointestinal tract microbiota plays a key role in the regulation of the pathogenesis

of several gastrointestinal diseases. In particular, the viral fraction, composed essentially of

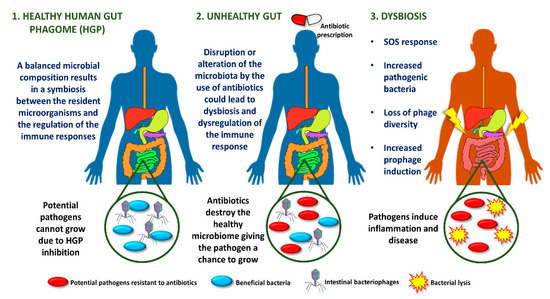

bacteriophages, influences homeostasis by exerting selective pressure on the bacterial communities living in the tract. The inflamed gut is associated with an SOS response regulated by an increase in resident intestinal pathogenic bacteria, loss of phage diversity, and induction of prophages.

- bacteriophage

- microbiome

- gastrointestinal tract

- dysbiosis

(Dear authors, the following contents are excerpts from your paper. They are editable.Most phages in the human intestine are temperate, suggesting that gut microbiome is fairly stable in the gastrointestinal tract. This idea has led to the establishment of a global intestinal phagome, showing a correlation between phages and health status, and his role in maintaining the structure and function of the intestinal microbiome [21]. This stability allows the maintenance of other microorganisms of the intestinal microbiota [22]. Interestingly, the prevalence of healthy intestinal phagome was found to be significantly altered in patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. Bacteriophage richness, measured by the number of taxa per sample, was showed to be higher in patients undergoing these diseases, while bacterial richness decreased concomitantly [13].

The type of this entry is interesting images. You can add some descriptions of the figures which makes the information more scientific.)The inflamed gut is associated with an SOS response regulated by an increase in resident intestinal pathogenic bacteria, loss of phage diversity, and induction of prophages. Several environmental conditions trigger the response to SOS bacterial stress, such as ultraviolet light, drugs or antibiotics [23]. As a clear example, most orally administered antibiotics alter the intestinal microbiota, promoting dysbiosis (Figure 1) [24].