ThScientifis study aims to assess tc consensus agrees that entrepreneurial activity is related to economic growth. The impacts of entrepreneurial framework conditions on economic growth based on the level of economic development in transition-driven economies and innovation-driven economies. The data were organised into a panel (2000–2019) and obtained from the National Expert Survey (NES), the Global Monitor Entrepreneurship (GEM), and the World Bank are assessed. By applying the generalised method of moments (GMM) estimation, weresearchers found that R&D transfer has a negative impact on economic growth that is innovation-driven, but positively impacts transition-driven economies. The results further highlighted that regardless of the level of development of the country, business and professional infrastructure do not positively impact economic growth. However, taxes and bureaucracy and physical and service infrastructure were shown to positively impact only innovation-driven economies, as in transition-driven economies, they were shown to have negative impacts on economic growth. The present study contributes to a better understanding of the link between economic growth and the conditions for entrepreneurship in economies with different degrees of economic growth. This study can serve as a basis for policy makers to adjust or develop new policies to accelerate economic growth.

- entrepreneurship

- framework conditions

- Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM)

- transition economies

- transition-driven economies

- innovation-driven economies

- economic growth

1. Introduction

2. Entrepreneurship and Economic Growth

Scientific consensus agrees that entrepreneurial activity is related to economic growth. However, the role of entrepreneurship in economic growth can be strongly influenced by the quality of governance or the business environment in which economic growth occurs (Khyareh and Amini 2021; Gu et al. 2021). Marshall (1961) and Krüger and Meyer (2021) see entrepreneurship as the spirit of adventure, the refoundation of the entrepreneur, giving him the capacity for the innovation necessary to maximize profits through identifying new market opportunities, surrounded by an inevitable level of risk and uncertainty. The relationship between entrepreneurship and regional economic growth has always been a hot topic among academics. However, the conclusions of this intense debate do not always converge in the same direction. Entrepreneurship often has a direct positive contribution to economic growth, but in some geographic areas, it may not necessarily be positive, as in the cases of some lagging or peripheral regions (Xu et al. 2021). Wennekers and Thurik (1999), in their article entitled ‘Linking Entrepreneurship and Economic Growth’, argued that economic growth is a key issue both in economic policymaking and economic research. In their study, they investigated the relationship between entrepreneurship and economic growth, summarising that both creating innovation and increasing competition are important for economic growth. This economic growth will be more robust the greater the network of entrepreneurial activity and business density. This mosaic is the state of growth and competitiveness in regions and nations (Stoica et al. 2020). In modern, open economies, entrepreneurship matters, and it is more important for economic growth than it has ever been (Audretsch and Thurik 1998). The performances of regional economies vary, particularly in terms of wages, salary growth, employment growth, and the ability to protect and commercialise industrial property rights associated with innovation, namely, through patents (Porter 2003; Lopes et al. 2022). In traditional location theory, there is a distinction between factors of production for which costs differ significantly between locations, on the one hand, and production inputs that are, in practice, available everywhere more or less at the same cost (Peris-Ortiz et al. 2018; Valliere and Peterson 2009). According to Shane (1993), and Liñán et al. (2013), the social and cultural norms influence the performance of entrepreneurial activity, resulting in wealth creation and economic growth. Shared trust and localised capability are present today in the so-called ‘learning regions’, where inter-organisational cooperation and the formation of sectoral clusters predominate, allowing synergy in terms of supply, production, promotion, and market response capacity (Farinha et al. 2020; Porter 2000). According to Martínez-Fierro et al. (2016), it is in less developed or less competitive countries that government policies and internal market dynamics are more impactful. In these regions, the emergence of complex networks between regional economic agents is more intense, not only at the level of inter-company relations, but in higher education institutions, RD&I laboratories, technological interface centres, collaborative laboratories, and digital innovation hubs, among others (Maskell and Malmberg 1999; Queiroz et al. 2020). Data analysis using the GEM and the Global Competitiveness Report (GCR) highlighted significant differences in the factors contributing to economic growth between emerging and advanced economies (Valliere and Peterson 2009; Farinha et al. 2018). According to Farinha et al. (2018) and Falciola et al. (2020), competitiveness can be defined as the ability of an economy to compete in the global market, its aptitude to attract capital, its ability to generate wealth, its job creation, and its social welfare, thereby depending on its capacity to produce and market high value-added solutions. As a key to success, competitiveness based on innovation factors represents a new impulse built based on the knowledge economy. The transition to the so-called ‘advanced economies’ stage implies the presence of ‘opportunity-driven’ entrepreneurship, capable of generating stable and successful companies, which pay good salaries and have solid contributions to the GDP per capita (Farinha et al. 2017; Civera et al. 2021). The authors argue that in countries in Asia and Oceania, the ‘factors of innovation and sophistication’ stand out in the ‘conditions of national framework’. In turn, ‘taxes and bureaucracy’ stand out in the context of ‘conditions to support entrepreneurship’. In Europe, ‘innovation and sophistication factors’ are also the most significant item of the ‘National Framework Conditions’, and ‘physical and service infrastructure’ and ‘funding for entrepreneurs’ are important aspects of ‘conditions to support the entrepreneurship’. As previously verified, some literature relates entrepreneurship to economic growth (Xu et al. 2021; Khyareh and Amini 2021; Farinha et al. 2020). Crowley and McCann (2018) examined firm-level productivity and innovation in Europe’s transition-driven and innovation-driven economies. The authors pointed to the need to study further the processes associated with entrepreneurial innovation in transition-driven economies and innovation-driven economies. Crowley and McCann (2018) indicated that transition-driven and innovation-driven economies are distinct because they operate in very different competitive, innovative, and institutional environments. The authors pointed to the need to further study the processes associated with entrepreneurial innovation in transition-driven economies and innovation-driven economies. Thus, no studies have simultaneously related entrepreneurial framework conditions with the degrees of development of economies, specifically transition-driven and innovation-driven economies. Farinha et al. (2020) and Stoica et al. (2020) indicated that they should do more to examine the effects of entrepreneurship on economic growth at the national level. The authors recommend that these new studies have larger and more diverse samples.3. Global Entrepreneurship Conditions

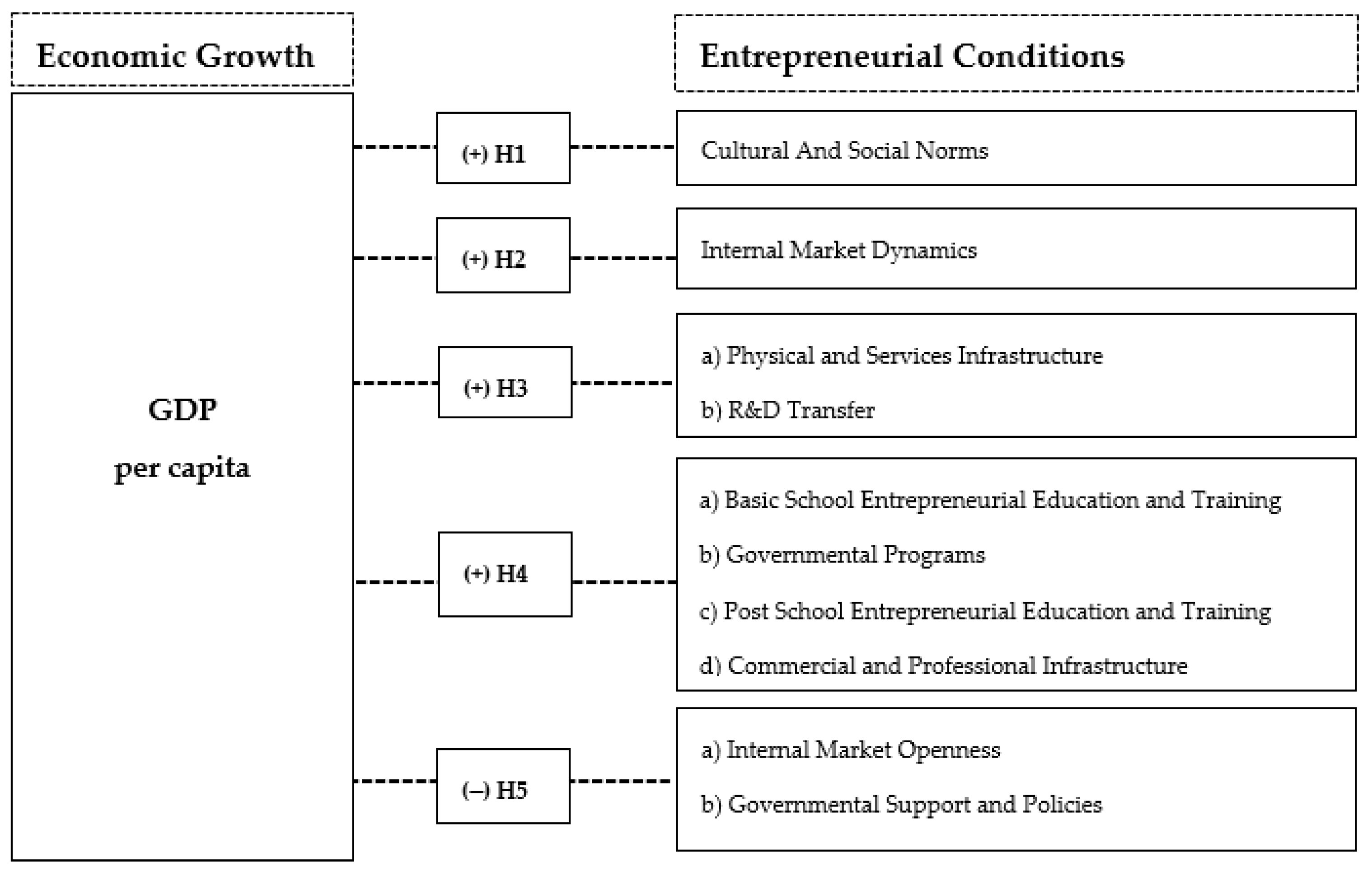

The GEM is a research program that focuses on entrepreneurship as one of any nation’s main engines of economic growth. From Porter, based on the Global Competitiveness Index, the GEM Conceptual Framework has had some evolution over time, reinforced by the recent influence of the COVID19 pandemic. Today, the model presents different ‘entrepreneurial phases’ and GEM entrepreneurship indicators (Reynolds et al. 2005). The conceptual model is based on a wide range of factors associated with the contextual characteristics of the countries’ entrepreneurial activity. At the base of its operationalisation is the carrying out of surveys among the adult population, through unstructured interviews with national experts, questionnaires addressed to national experts, and analysis of relevant measures based on existing transnational datasets (Reynolds et al. 2005; GEM 2021b). Concerning entrepreneurial framework conditions, the analysis of the main components was performed to derive 12 latent variables: (1) access to entrepreneurial finance; (2) government policy: support and relevance; (3) government policy: taxes and bureaucracy; (4) government entrepreneurship programs; (5) entrepreneurial education at school; (6) entrepreneurial education post-school; (7) research and development transfer; (8) commercial and professional infrastructure; (9) ease of entry: market dynamics; (10) ease of entry: market burdens and regulations; (11) physical infrastructure; (12) social and cultural norms (GEM 2021a). According to Marques et al. (2011) and Sommarström et al. (2020), the school-business cooperation allows for achieving more ambitious goals of entrepreneurial learning, having positive effects at the level of economic development of the economy. Governmental programs aim to foster an innovative spirit, promote entrepreneurship, and give rise to new companies and new business models with added value in the market (Acs and Amorós 2008; Martinez-Fierro et al. 2015; Medrano et al. 2020). Various studies on entrepreneurship have pointed out that commercial and professional infrastructures are crucial for the success of the entrepreneurial activity, and thus, for countries’ economic growth (Reynolds et al. 2005; Peris-Ortiz et al. 2018; Li et al. 2020). According to Sun et al. (2020) and Bertoni and Tykvová (2015), government funding and support for entrepreneurial activity stimulates the development of entrepreneurial activity and the growth of an economy. Various studies on entrepreneurship have pointed out that commercial and professional infrastructures are crucial for the success of the entrepreneurial activity, and henceforth, for countries’ economic growth (Reynolds et al. 2005; Peris-Ortiz et al. 2018; Li et al. 2020). Lepoutre et al.’s (2013) study interpreted some limitations in its impact on countries’ economic growth. Figure 1 shows the research model and the hypotheses formulated.

References

- Acs, Zoltan. 2006. How is entrepreneurship good for economic growth? Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization 1: 97–107.

- Carree, Martin, and Roy Thurik. 2010. The Impact of Entrepreneurship on Economic Growth. In Handbook of Entrepreneurship Research: An Interdisciplinary Survey and Introduction. Edited by Zoltan Acs and David Audretsch. New York: Springer, pp. 557–94.

- Lopes, João, Helder Antunes, and Ricardo Rodrigues. 2018a. Comparative Entrepreneurship between Western Europe and Latin America. Entrepreneurship Research Journal 8: 1–20.

- Urbano, David, and Sebastian Aparicio. 2016. Entrepreneurship capital types and economic growth: International evidence. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 102: 34–44.

- Acs, Zoltan, David Audretsch, Pontus Braunerhjelm, and Bo Carlsson. 2012. Growth and entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics 39: 289–300.

- Audretsch, David, and Max Keilbach. 2004. Entrepreneurship Capital and Economic Performance. Regional Studies 38: 949–59.

- Stoica, Ovidiu, Angela Roman, and Valentina D. Rusu. 2020. The Nexus between Entrepreneurship and Economic Growth: A Comparative Analysis on Groups of Countries. Sustainability 12: 1186.

- Stam, Erik, and André Van Stel. 2011. Types of entrepreneurship and economic growth. In Entrepreneurship, Innovation, and Economic Development. Edited by Adam Szirmai, Wim Naudé and Micheline Goedhuys. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 78–95.

- Díez-Martín, Francisco, Alicia Blanco-González, and Camilo Prado-Román. 2016. Explaining nation-wide differences in entrepreneurial activity: A legitimacy perspective. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 12: 1079–102.

- Acs, Zoltan, Saul Estrin, Tomasz Mickiewicz, and László Szerb. 2018. Entrepreneurship, institutional economics, and economic growth: An ecosystem perspective. Small Business Economics 51: 501–14.

- Lopes, João, and Mário Franco. 2019. Review About Regional Development Networks: An Ecosystem Model Proposal. Journal of the Knowledge Economy 10: 275–97.

- Sitaridis, Ioannis, and Fotis Kitsios. 2020. Competitiveness analysis and evaluation of entrepreneurial ecosystems: A multi-criteria approach. Annals of Operations Research 294: 377–99.

- Steigertahl, Lisa, and René Mauer. 2021. Investigating the success factors of the Nordic entrepreneurial ecosystem—Talent transformation as a key process. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation.

- Cavallo, Angelo, Antonio Ghezzi, and Raffaello Balocco. 2019. Entrepreneurial ecosystem research: Present debates and future directions. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 15: 1291–321.

- Farinha, Luís, João Lopes, Sharmistha Bagchi-Sen, João Renato Sebastião, and José Oliveira. 2020. Entrepreneurial dynamics and government policies to boost entrepreneurship performance. Socio-Economic Planning Sciences 72: 100950.

- Amorós, José Ernesto, Christian Felzensztein, and Eli Gimmon. 2013. Entrepreneurial opportunities in peripheral versus core regions in Chile. Small Business Economics 40: 119–39.

- Bosma, Niels, Zoltan Acs, Erkko Autio, Alicia Coduras, and Jonathan Levie. 2008. 2008 Executive Report. London: Global Entrepreneurship Monitor.

- Crowley, Frank, and Philip McCann. 2018. Firm innovation and productivity in Europe: Evidence from innovation-driven and transition-driven economies. Applied Economics 50: 1203–21.

- Khyareh, Mohsen Mohammadi, and Hadi Amini. 2021. Governance quality, entrepreneurship and economic growth. Journal of Competitiveness 13: 41–64.

- Gu, Wentao, Jiaye Wang, Xiyuan Huan, and Zhongdi Liu. 2021. Entrepreneurship and high-quality economic development: Based on the triple bottom line of sustainable development. International Entrepreneurship and Management Jounal 17: 1–27.

- Marshall, Alfred. 1961. Principles of Economics. London: Macmillan, vol. 1.

- Krüger, Niel Almero, and Natanya Meyer. 2021. The Development of a Small and Medium-Sized Business Risk Management Intervention Tool. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 14: 310.

- Xu, Bing, Haijing Yu, and Lili Li. 2021. The impact of entrepreneurship on regional economic growth: A perspective of spatial heterogeneity. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development 33: 309–31.

- Wennekers, Sander, and Roy Thurik. 1999. Linking Entrepreneurship and Economic Growth. Small Business Economics 13: 27–56.

- Audretsch, David, and Roy Thurik. 1998. The Knowledge Society, Entrepreneurship, and Unemployment. Champaign: University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign’s Academy for Entrepreneurial Leadership Historical Research Reference in Entrepreneurship (SSRN Electronic Library).

- Porter, Michael. 2003. The Economic Performance of Regions. Regional Studies 37: 549–78.

- Lopes, João M., Sofia Gomes, Rosselyn Pacheco, Elizabete Monteiro, and Carolina Santos. 2022. Drivers of Sustainable Innovation Strategies for Increased Competition among Companies. Sustainability 14: 5471.

- Peris-Ortiz, Marta, João Ferreira, and Cristina Fernandes. 2018. Do Total Early-stage Entrepreneurial Activities (TEAs) foster innovative practices in OECD countries? Technological Forecasting and Social Change 129: 176–84.

- Valliere, Dave, and Rein Peterson. 2009. Entrepreneurship and economic growth: Evidence from emerging and developed countries. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 21: 459–80.

- Shane, Scott. 1993. Cultural influences on national rates of innovation. Journal of Business Venturing 8: 59–73.

- Liñán, Francisco, Isidoro Romero Luna, and José Fernández Serrano. 2013. Necessity and opportunity entrepreneurship: The mediating effect of culture. Revista de Economía Mundial 33: 21–47.

- Porter, Michael E. 2000. Location, Competition, and Economic Development: Local Clusters in a Global Economy. Economic Development Quarterly 14: 15–34.

- Martínez-Fierro, Salustiano, José María Biedma-Ferrer, and José Ruiz-Navarro. 2016. Entrepreneurship and strategies for economic development. Small Business Economics 47: 835–51.

- Maskell, Peter, and Anders Malmberg. 1999. The Competitiveness of Firms and Regions:‘Ubiquitification’ and the Importance of Localized Learning. European Urban and Regional Studies 6: 9–25.

- Queiroz, Jonas, Paulo Leitão, Joseane Pontes, André Chaves, Javier Parra-Domínguez, and María Perez-Pons. 2020. A Quality Innovation Strategy for an Inter-regional Digital Innovation Hub. Adcaij-Advances in Distributed Computing and Artificial Intelligence Journal 9: 31–45.

- Farinha, Luís, Joao Ferreira, and Sara Nunes. 2018. Linking innovation and entrepreneurship to economic growth. Competitiveness Review 28: 451–75.

- Falciola, Justine, Marion Jasen, and Valentina Rollo. 2020. Defining firm competitiveness: A multidimensional framework. World Development 129: 104857.

- Farinha, Luís, Joao Ferreira, Sara Nunes, and Vanessa Ratten. 2017. Conditions supporting entrepreneurship and sustainable growth. International Journal of Social Ecology and Sustainable Development 8: 67–86.

- Civera, Josefina, Mabel Pisá Bó, and José Fernando López-Muñoz. 2021. Do contextual factors influence entrepreneurship? Spain’s regional evidences. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 17: 105–29.

- Reynolds, Paul, Niels Bosma, Erkko Autio, Steve Hunt, Natalie De Bono, Isabel Servais, Paloma Lopez-Garcia, and Nancy Chin. 2005. Global entrepreneurship monitor: Data collection design and implementation 1998–2003. Small Business Economics 24: 205–31.

- GEM. 2021b. Entrepreneurial Framework Conditions (EFCs). Available online: https://www.gemconsortium.org/wiki/1154 (accessed on 11 June 2021).

- GEM. 2021a. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. Available online: https://www.gemconsortium.org/data/key-nes (accessed on 26 May 2021).

- Marques, Carla Susana, João Ferreira, Ricardo Gouveia Rodrigues, and Mariza Ferreira. 2011. The contribution of yoga to the entrepreneurial potential of university students: A SEM approach. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 7: 255–78.

- Sommarström, Kaarina, Elena Oikkonen, and Timo Pihkala. 2020. Entrepreneurship Education with Companies: Teachers Organizing School-Company Interaction. Education Sciences 10: 268.

- Acs, Zoltan, and José Ernesto Amorós. 2008. Entrepreneurship and competitiveness dynamics in Latin America. Small Business Economics 31: 305–22.

- Martinez-Fierro, Salustiano, Jose Maria Biedma-Ferrer, and Jose Maria Biedma-Ferrer. 2015. Entrepreneurial Framework Conditions and Economic Development: An Analysis of Gem Countries. Revista de Economía Mundial, 181–212.

- Medrano, Natalia, María Cornejo-Cañamares, and Cristina Olarte-Pascual. 2020. The impact of marketing innovation on companies’ environmental orientation. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing 35: 1–12.

- Li, Cai, Naveed Ahmed, Sikandar A. Qalati, Asadullah Khan, and Shumaila Naz. 2020. Role of Business Incubators as a Tool for Entrepreneurship Development: The Mediating and Moderating Role of Business Start-Up and Government Regulations. Sustainability 12: 1822.

- Sun, Huaping, Aminatou Kemajou Pofoura, Isaac Adjei Mensah, Liang Li, and Muhammad Mohsin. 2020. The role of environmental entrepreneurship for sustainable development: Evidence from 35 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. Science of The Total Environment 741: 140132.

- Bertoni, Fabio, and Tereza Tykvová. 2015. Does governmental venture capital spur invention and innovation? Evidence from young European biotech companies. Research Policy 44: 925–35.

- Lepoutre, Jan, Rachida Justo, Siri Terjesen, and Niels Bosma. 2013. Designing a global standardized methodology for measuring social entrepreneurship activity: The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor social entrepreneurship study. Small Business Economics 40: 693–714.