1. Introduction

the environmental impact of the technologies employed for basic functions concerning water/air quality control or energy, along with their dependence on finite resources, has become a significant issue, increasing the interest in green technologies power by light [1][2][3][5,6,7]. One such green and affordable technology for water purification is photocatalysis, utilizing light-activated semiconductors (SCs). In many applications, there is great interest in composite materials that offer the combined advantages of their respective components [4][5][6][8,9,10], with photocatalytic composites being especially effective in the removal of pollutants from aquatic solutions. There are several requirements in order to prepare a good composite photocatalyst. Among the desired attributes is a wider wavelength-range light response (UV and visible) and, ideally, a good response under solar light. Another significant need is the ease of removal of the photocatalytic material from the treated water solution, as often the photocatalyst itself can cause issues for the water quality. Silver-enhanced magnetic materials, which can fulfil these requirements, have seen a surge in popularity. Magnetic materials are a common type of photocatalyst, from iron oxides to the spinel ferrite family (MFe2O4, where M is a divalent metal cation), whose magnetic properties offer several enhancements when used alone or as part of a composite photocatalyst, with a primary advantage being their easy removal from a solution through magnetic means (such as a simple magnet). On the other hand, silver (Ag) nanoparticles, having a low cost [7][11] and offering plasmonic-based enhancements [7][11] and antibacterial properties [8][12] are a great fit as components in photocatalytic composites for water purification under a wide irradiation wavelength range.

2. Photocatalysis for Pollutant Removal

As a byproduct of the industrial revolution, numerous types of pollutants, from organic compounds to pathogenic microbes, have risen to threaten humans and the general environment and, in response, numerous methods have been designed and employed for polluted water treatment. Concerning organic pollutants, the employment of dyes and water by textile and plastic industries for coloring purposes, leads to harmful dye-based pollutants in wastewater with adverse effects on the environment

[9][15]. Many techniques used for the removal of organic compounds often require additional treatment of byproducts. There is also the issue of non-organic pollutants: one of the more infamous pollutants, hexavalent chromium (Cr

6+)

[10][16], originating from the waste products of the chrome electroplating industry, presents carcinogenic properties that make it an extremely dangerous water pollutant. The high cost of Cr

6+ removal techniques, such as coagulation or reverse osmosis, usually restricts them to large-scale utilization. With harmful waste from industrial sources, that do not naturally degrade, and chemicals from agricultural/pharmaceutical products finding their way into the environment, the need for a sustainable low-cost method for pollutant removal is becoming increasingly more urgent. An environmentally friendly method that can target a variety of pollutant types is photocatalysis

[11][17].

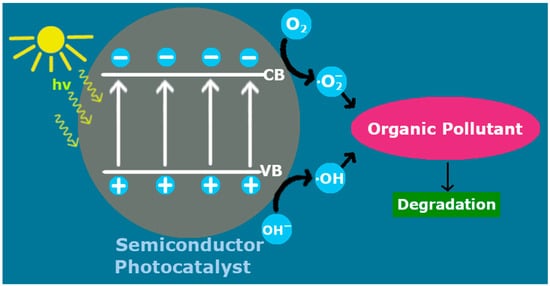

In a typical photocatalytic process, after a semiconductor is irradiated with photons of higher energy than its band gap, electron/hole pairs are generated in its conduction/valence bands. These charged pairs are able to reduce/oxidize adjacent molecules, provided that the energy bands of the photocatalyst are properly positioned relative to the reactant’s redox levels

[11][17]. However, a possible recombination of the electrons/holes can impair this activity. The photoexcited electrons can reduce adsorbed O

2 into superoxide radicals (

·O

2), while the reaction of H

2O with holes leads to hydroxyl radicals (

·OH)

[12][18]. These radicals, in turn, can function as active species for the decomposition of a pollutant (

Figure 1). For example, the hydroxyl radicals can oxidize organic compounds into small and much less toxic molecules

[13][19]. The application of photocatalysis extends even further than organic pollutant degradation: photocatalytic chromium treatment can be an affordable, green and efficient technique for the neutralization of this dangerous pollutant; Cr

6+ can be reduced to its trivalent variation, Cr

3+, which presents severely lower toxicity, via a photocatalytic reduction reaction

[10][14][15][16][16,20,21,22].

Figure 1.

Photocatalytic treatment of organic pollutants by an irradiated photocatalyst.

The most common photocatalytic materials are metal oxides

[12][18]. The photon energy of the irradiation must exceed the band gap of the catalyst for proper absorption and charge separation and TiO

2, the most well-known photocatalyst, with its 3.2 eV band gap, absorbs a negligent portion of visible light, thus it is only suitable for photocatalytic operation under UV light. However, a photocatalyst should be active under both UV and visible light

[12][17][18,23]. This is the case with magnetic hematite (α-Fe

2O

3)

[18][19][24,25], which has significant absorption in the sunlight spectrum (around 40%) due to its smaller band gap

[12][18]. Visible-range light absorption can be expected from several magnetic materials (e.g., the MFe

2O

4 family)

[14][20][20,26].

3. Magnetic Materials and Silver Enhancement

Among the most common magnetic materials used in photocatalysis are iron oxides having appropriate valence energy levels and narrow band gaps together with corrosion resistance and stability under irradiation. Besides FeO (iron (II) oxide), the most interesting forms in which iron oxides can be obtained through the usual synthesis methods are α/γ-Fe

2O

3 (iron (III) oxide phases: hematite/maghemite) and Fe

3O

4 (magnetite = Fe(II)Fe(III)

2O

4), with differences in their saturation magnetization and other attributes

[21][27] (Hematite is anti-ferromagnetic material with small bulk magnetic susceptibility, while magnetite and maghemite are ferrimagnetic with large bulk magnetic susceptibility

[22][28]). In general, ferrites (ferrimagnetic materials with great stability and tolerance to even severe basic/acidic conditions) are very promising for water treatment applications

[14][23][20,29]. Though there are different types of ferrite structure, the category of ferrites that holds the most significance are the semiconducting spinel ferrites (also known as ferrospinels): cubic MFe

2O

4 structures, with M being a divalent cation such as cobalt, zinc, magnesium

, and soetc. [30] o

n [24] or combinations of them

[25][31]. They are characterized by high saturation magnetization and increased permeability among other interesting properties, resulting in an upsurge of related research in recent years

[22][28]. For spinel ferrite magnetic nanostructures specifically, known advantages include chemical stability, mechanical hardness and high magnetic coercivity

[26][32]. In general, the aggregation state of magnetic nanoparticles can affect their magnetic behavior and ferrospinel nanoparticles, in particular, usually exhibit superparamagnetic behavior (with an absence of remnant magnetization), while in cluster form they can exhibit ferrimagnetic behavior

[27][33].

Magnetic photocatalysts, in general, have attracted significant interest due to the effects of intrinsic and external magnetic fields on them and the enhancements that their manipulation can offer to photocatalytic water purification applications. It is known that external magnetic field application during photocatalytic reactions can enhance e

−h

+ (electron/hole) charge-carrier separation via Lorentz forces in opposite directions and suppress recombination phenomena

[21][28][29][30][27,34,35,36]. Furthermore, the application of an external magnetic field can result in the exertion of Lorentz force to both the photocatalyst as well as the pollutant in opposite directions, achieving proximity and contaminant adsorption on the catalyst surface

[31][37]. In the case of ferromagnetic photocatalysts, an external magnetic field also leads to electron spin alignment in the material’s domains, frequently resulting in negative magnetoresistance, which facilitates charge transfer

[30][36]. Overall, composites with ferromagnetic materials show increased pollutant degradation rates with the increase in the applied external magnetic field strength

[32][38], and, in cases where the resulting alignment of magnetic moments is the same for different components of the composite, facile electron migration through the interface has been reported

[33][39]. Additionally, the manipulation of the photocatalysts’ electron spin polarization states by methods such as doping has also been thought to suppress charge-carrier recombination. In such magnetic semiconductors, flipping the electrons’ spin state can occur via spin–orbit or hyperfine coupling and the recombination between photoexcited e

− and h

+ can be prohibited

[30][36]. Most importantly, the presence of a magnetic material as part of a photocatalytic composite makes it easily recoverable after the end of the photocatalytic process by applying an external magnetic field. The ability to easily retrieve a magnetic photocatalyst also allows for their feasible reuse, as the retrieved material can have its adsorbed contaminants desorbed to render it able for repeated water treatment processes

[34][40].

Lately, the combination of silver with magnetic materials has attracted significant interest. Most of their enhancements brought about by silver nanoparticles are based on their localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) effect, caused by their surface electrons’ dipolar oscillation induced by the polarizing incident light’s electric field. In metal nanoparticles, the electric field of incident light causes displacement of the free electrons from the stationary positive charge (core) and a restoring force that appears, leading to their dipolar oscillation

[7][11]. The term “surface plasmons’’ refers to this surface-localized oscillation of the metals’ free charge. When the incident light frequency matches the natural oscillating frequency of these surface electrons, the LSPR effect is activated with the occurrence of increased light absorption

[7][12][11,18].

The merging of a semiconductor with plasmonic nanoparticles (NPs) is a very effective strategy for enhanced photocatalytic pollutant degradation

[35][41]. Because of the LSPR-induced light absorption enhancement, plasmonic nanoparticle integration can improve a semiconductor’s response to light. In cases of plasmonic NPs with visible light activated-LSPR, the photoactivity of even wide band gap semiconductors, such as TiO

2, can be extended toward the visible region with their integration

[36][42]. Among the most well-known LSPR-induced enhancement mechanisms in composites are: (a) the light scattering mechanism that lengthens the photons’ effective path

[37][43], (b) a local electric field enhancement on the plasmonic particle surface which results in greater charged-pair production in that area

[38][44], (c) the electron injection mechanism of ‘’hot’’ (excited with high kinetic energy) electrons that can overcome the Schottky barrier (at the semiconductor/metallic nanoparticle interface) and transfer to the semiconductor from the plasmonic NPs

[36][42], and (d) the plasmon-induced resonance energy transfer (PIRET, a dipole–dipole interaction-based non-radiative energy transfer to the semiconductor, which is especially significant when there is an overlap of the semiconductor band edge with the plasmonic absorption band)

[37][43]. Moreover, a direct electron transfer from the plasmonic NPs to the energy states of the pollutant adsorbate is also possible

[39][45]. Finally, besides the plasmonic-based enhancements, photocatalysis can benefit from the storage of excited semiconductor electrons in the Fermi level of metal nanoparticles, shifting the Fermi potential to more negative values, which improves charge separation. These mechanisms, along with the presence of the Schottky barrier aiding electron/hole separation

[40][46], lead to enhanced photocatalytic activity

[12][18]. Silver nanoparticles, in particular, have an especially intense LSPR effect

[36][42] and are considered to be the noble metal-based nanoparticles with the lowest cost

[7][11]. The frequency of their surface plasmon resonance can be modified through their morphology, thereby tuning their optical response

[12][18]. Thus, visible-light-induced photocatalytic enhancements become possible in silver-integrated semiconductors

[41][47].

An important factor to consider when designing materials for water treatment is the sensitivity of these materials to the environment. Though silver NPs have been known to be susceptible to oxidation, good chemical stability can be achieved by utilizing modern synthetic methods designed for this purpose. This is usually done by stabilizing agents in colloidal nanoparticle suspensions. Such agents used in photocatalytic applications are surfactants, silica, polymers, and metal shells, summarized in a relatively recent analytical review

[42][48]. More sophisticated approaches are followed in order to obtain extra stable nanoparticles such as the use of a protective ligand shell of p-mercaptobenzoic acid in a notable Ag NP synthetic process, which results in the formation of a closed-shell superatom with 18 de-localized electrons accompanied by the opening of a stabilizing energy gap

[43][49]. It is important to note that additional components, such as intermediate layers, in SC/silver composites can affect the plasmonic properties of the material and conscious selection and tailoring is required. A thinner interlayer, for example, is known to cause a red shift in the required SPR wavelength

[44][50]. Often, there has to be a compromise between the maintenance of nanoparticle stability and the achievement of efficient plasmonic properties, since the presence of protective layers affects the vicinity of the plasmonic NP toward the SC surface and toward the pollutant adsorbate

[42][48]. For Ag NP, thin protective layers in the subnanometer range are preferred in photocatalytic applications

[45][51].

Another important issue is that, while nanosilver is known to be an excellent antibacterial agent, it has inherent toxicity

[46][53] and, after its function during water treatment is completed, effective separation is needed. For this purpose, magnetic materials are often suggested as base materials for Ag-composites, as the removal of the composites can occur easily with an applied magnetic field

[47][48][13,14].

Another area in which the magnetic substrate can manipulate the integrated plasmonic nanostructures is in their orientational control, thereby allowing for the tuning of the LSPR peak intensity

[49][59]. Plasmonic–magnetic nanocomposites that are responsive to magnetic forces offer a remote and reversible way to control anisotropically shaped plasmonic nanostructures (e.g., nanorods) under external magnetic fields. For example, the selective orientation of plasmonic nanorods parallel to light polarization activates longitudinal LSPR modes with enhanced LSPR peak intensity

[50][60].

In general, silver integration is a popular enhancement method for photocatalysts, able to target a variety of pollutants. In a recent work, Ibrahim et al. (2022) observed significantly enhanced photocatalytic pollutant removal efficiency after silver integration for their best TiO

2/g-C

3N

4/Ag sample in both oxidation (azo-dyes/pharmaceuticals) and reduction (Cr

6+ and 4-nitrophenol) processes

[51][61]. Composites with magnetic materials and silver have been proven to be especially efficient in the treatment of heavy metal pollutants, such as Cr

6+ [14][20] or organics such as methylene blue

[6][52][53][10,62,63], rhodamine B

[6][40][54][55][10,46,64,65], malachite green

[53][56][63,66] and phenol

[53][57][63,67], along with the photocatalytic neutralization of bacteria such as Escherichia coli

[53][58][63,68] and Micrococcus luteus

[53][63]. Improvements in photocatalytic pollutant removal efficiency arising from silver integration onto magnetic materials are also evident in the case of pharmaceutical pollutants such as tetracycline

[59][69] and sulfanilamide

[60][70]. The silver addition has been proven to enhance the photocatalytic degradation and antibacterial action, not only under UV but under visible illumination as well

[6][14][40][52][56][58][10,20,46,62,66,68], even when the base materials are not especially effective under these conditions

[14][20]. In summary, the combined attributes of magnetic materials and silver lead to significantly enhanced composites with usage flexibility.