Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome (STEC-HUS) belongs to the body of thrombotic microangiopathies [1], a heterogeneous group of diseases characterized by a triad of features: thrombocytopenia, mechanical hemolytic anemia with schistocytosis, and ischemic organ damage. It is caused by gastrointestinal infection by a Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (and occasionally other pathogens) and is also called “typical” HUS, as opposed to “atypical” HUS, which results from alternative complement pathway dysregulation, and “secondary” HUS, caused by various co-existing conditions.

- Shiga toxin

- Escherichia coli

- hemolytic uremic syndrome

1. STEC-HUS as a Zoonosis: Reservoirs, Sources, and Modes of Transmission

The importance of cattle as the primary reservoir for STEC has been hypothesized since the first outbreaks associated with undercooked hamburgers [17][1]. Occasionally, sheep [76][2] or goats [77][3] have been reported as sources of outbreaks. Cattle are asymptomatic carriers of STEC: after internalization in bovine epithelial cells, Shiga toxin is excluded from the endoplasmic reticulum and localizes to lysosomes, where its cytotoxicity is abrogated [78][4]. Reported prevalence in farm and slaughterhouse studies varies widely, but a recent meta-analysis yielded an estimated prevalence of E. coli O157:H7 in North America of 10.68% (95% CI: 9.17%–12.28%) in fed beef, 4.65% (95% CI: 3.37%–6.10%) in adult beef, and 1.79% (95% CI: 1.20%–2.48%) in adult dairy. In winter months, the prevalence was nearly 50% lower than that recorded in the summer months [79][5], consistent with the seasonality observed in human infections [80][6]. Contamination by EHEC decreases during processing of the meat [81][7], but some authors reported that salt at concentrations used for this process may in fact enhance Stx production [82][8]. Among animals positive for STEC, the term “super-shedder” is applied to cattle that shed concentrations of E. coli O157:H7 ≥ 10⁴ colony-forming units/g feces. The role of ground beef as a vehicle for STEC seems to be decreasing, and recent outbreaks have been associated with raw milk products, spinach [88][9], municipal drinking water [89][10], or fenugreek [90][11]. In a retrospective analysis of 350 outbreaks in the USA between 1982 and 2002, Rangel and colleagues found that 52% of outbreaks were foodborne (including 21% for which ground beef was the transmission route), 14% resulted from person to person transmission, and 6% from recreational water. The transmission route remained unknown after investigation in 21% of outbreaks [91][12]. It is noteworthy that E. coli can survive for months in the environment, potentially leading to the contamination of fresh produce [92][13].

1.1. Global Burden, Spatial and Temporal Distribution of STEC-HUS Cases

1.2. Propensity to Develop STEC-HUS

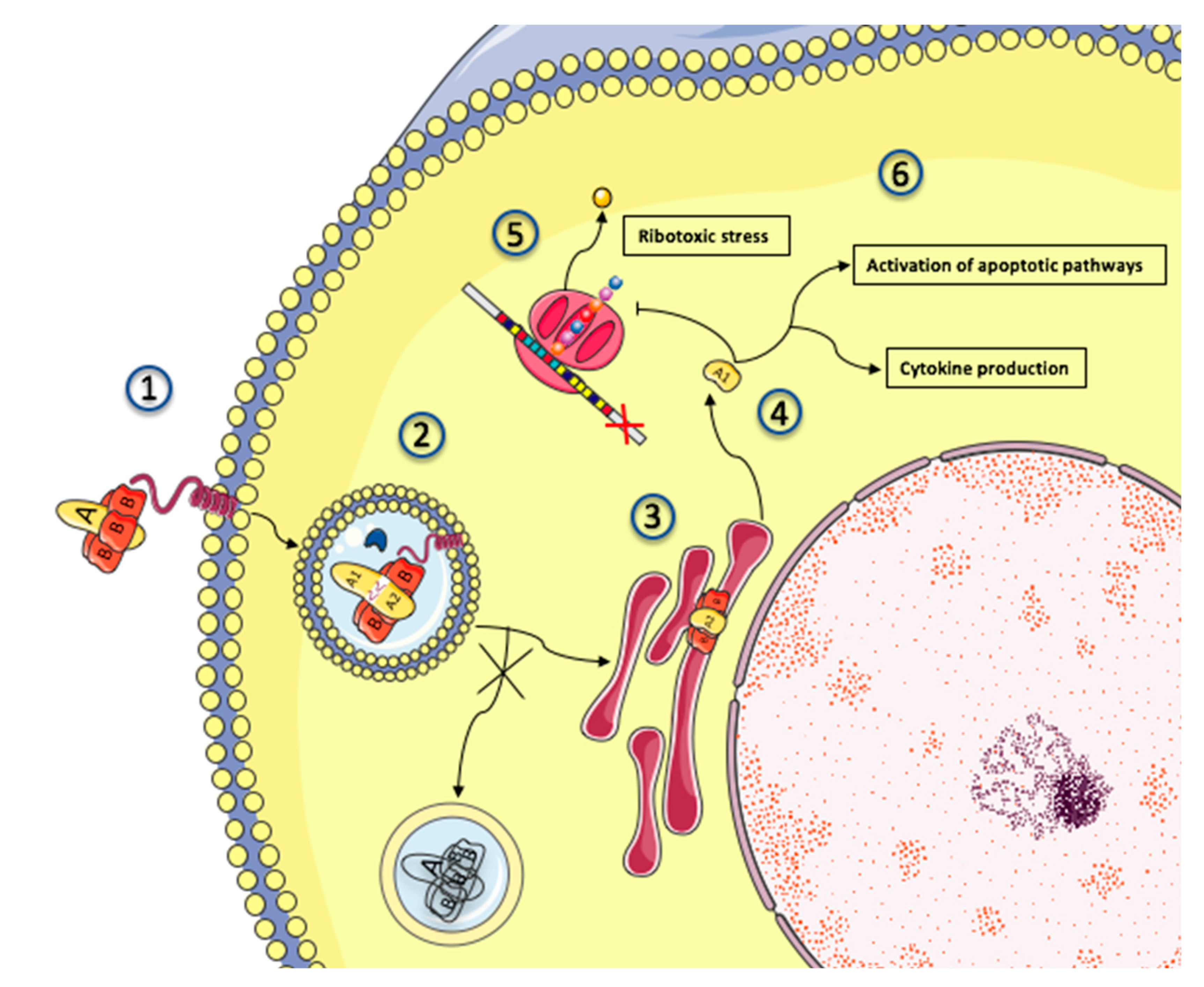

2. Pathogenesis

2.1. Colonization of the Bowel: The Attaching and Effacing Phenotype

2.2. Shiga Toxin Production and Effect: Gb3 Fixation and Trafficking

2.3. Mechanisms of Shiga Toxin Cytotoxicity

2.4. Activation of Complement Pathways: Culprit or Innocent Bystander?

2.5. Endothelial Damage: From Stx Cytotoxicity to Thrombotic Microangiopathy

References

- Riley, L.W.; Remis, R.S.; Helgerson, S.D.; McGee, H.B.; Wells, J.G.; Davis, B.R.; Hebert, R.J.; Olcott, E.S.; Johnson, L.M.; Hargrett, N.T.; et al. Hemorrhagic colitis associated with a rare Escherichia coli serotype. N. Engl. J. Med. 1983, 308, 681–685.

- Ogden, I.D.; Hepburn, N.F.; MacRae, M.; Strachan, N.J.C.; Fenlon, D.R.; Rusbridge, S.M.; Pennington, T.H. Long-term survival of Escherichia coli O157 on pasture following an outbreak associated with sheep at a scout camp. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2002, 34, 100–104.

- Bielaszewska, M.; Janda, J.; Bláhová, K.; Minaríková, H.; Jíková, E.; Karmali, M.A.; Laubova, J.; Scikulova, J.; Preston, M.A.; Khakhria, R.; et al. Human Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection associated with the consumption of unpasteurized goat’s milk. Epidemiol. Infect. 1997, 119, 299–305.

- Hoey, D.E.E.; Sharp, L.; Currie, C.; Lingwood, C.A.; Gally, D.L.; Smith, D.G.E. Verotoxin 1 binding to intestinal crypt epithelial cells results in localization to lysosomes and abrogation of toxicity. Cell Microbiol. 2003, 5, 85–97.

- Ekong, P.S.; Sanderson, M.W.; Cernicchiaro, N. Prevalence and concentration of Escherichia coli O157 in different seasons and cattle types processed in North America: A systematic review and meta-analysis of published research. Prev. Vet. Med. 2015, 121, 74–85.

- Bruyand, M.; Mariani-Kurkdjian, P.; Hello, S.L.; King, L.-A.; Cauteren, D.V.; Lefevre, S.; Gouali, M.; Silva, N.J.-D.; Mailles, A.; Donguy, M.-P.; et al. Paediatric haemolytic uraemic syndrome related to Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli, an overview of 10 years of surveillance in France, 2007 to 2016. Eurosurveillance 2019, 24.

- Elder, R.O.; Keen, J.E.; Siragusa, G.R.; Barkocy-Gallagher, G.A.; Koohmaraie, M.; Laegreid, W.W. Correlation of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157 prevalence in feces, hides, and carcasses of beef cattle during processing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 2999–3003.

- Harris, S.M.; Yue, W.-F.; Olsen, S.A.; Hu, J.; Means, W.J.; McCormick, R.J.; Du, M.; Zhu, M.-J. Salt at concentrations relevant to meat processing enhances Shiga toxin 2 production in Escherichia coli O157:H7. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2012, 159, 186–192.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Importance of culture confirmation of shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli infection as illustrated by outbreaks of gastroenteritis—New York and North Carolina, 2005. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2006, 55, 1042–1045.

- Salvadori, M.I.; Sontrop, J.M.; Garg, A.X.; Moist, L.M.; Suri, R.S.; Clark, W.F. Factors that led to the Walkerton tragedy. Kidney Int. Suppl. 2009, S33–S34.

- Buchholz, U.; Bernard, H.; Werber, D.; Böhmer, M.M.; Remschmidt, C.; Wilking, H.; Deleré, Y.; an der Heiden, M.; Adlhoch, C.; Dreesman, J.; et al. German outbreak of Escherichia coli O104:H4 associated with sprouts. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 1763–1770.

- Rangel, J.M.; Sparling, P.H.; Crowe, C.; Griffin, P.M.; Swerdlow, D.L. Epidemiology of Escherichia coli O157:H7 Outbreaks, United States, 1982–2002. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2005, 11, 603–609.

- Park, S.; Szonyi, B.; Gautam, R.; Nightingale, K.; Anciso, J.; Ivanek, R. Risk Factors for Microbial Contamination in Fruits and Vegetables at the Preharvest Level: A Systematic Review. J. Food Prot. 2012, 75, 2055–2081.

- Majowicz, S.E.; Scallan, E.; Jones-Bitton, A.; Sargeant, J.M.; Stapleton, J.; Angulo, F.J.; Yeung, D.H.; Kirk, M.D. Global incidence of human Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli infections and deaths: A systematic review and knowledge synthesis. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2014, 11, 447–455.

- Rivas, M.; Chinen, I.; Miliwebsky, E.; Masana, M. Risk Factors for Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli-Associated Human Diseases. Microbiol. Spectr. 2014, 2.

- Frenzen, P.D.; Drake, A.; Angulo, F.J. Emerging Infections Program FoodNet Working Group. Economic cost of illness due to Escherichia coli O157 infections in the United States. J. Food Prot. 2005, 68, 2623–2630.

- Buzby, J.C.; Roberts, T. The economics of enteric infections: Human foodborne disease costs. Gastroenterology 2009, 136, 1851–1862.

- Williams, D.M.; Sreedhar, S.S.; Mickell, J.J.; Chan, J.C.M. Acute kidney failure: A pediatric experience over 20 years. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2002, 156, 893–900.

- Thorpe, C.M. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004, 38, 1298–1303.

- Rivas, M.; Miliwebsky, E.; Chinen, I.; Roldán, C.D.; Balbi, L.; García, B.; Fiorilli, G.; Sosa-Estani, S.; Kincaid, J.; Rangel, J.; et al. Characterization and epidemiologic subtyping of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli strains isolated from hemolytic uremic syndrome and diarrhea cases in Argentina. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2006, 3, 88–96.

- Elliott, E.J.; Robins-Browne, R.M.; O’Loughlin, E.V.; Bennett-Wood, V.; Bourke, J.; Henning, P.; Hogg, G.G.; Knight, J.; Powell, H.; Redmond, D.; et al. Nationwide study of haemolytic uraemic syndrome: Clinical, microbiological, and epidemiological features. Arch. Dis. Child. 2001, 85, 125–131.

- Vally, H.; Hall, G.; Dyda, A.; Raupach, J.; Knope, K.; Combs, B.; Desmarchelier, P. Epidemiology of Shiga toxin producing Escherichia coli in Australia, 2000–2010. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 63.

- Karmali, M.A.; Mascarenhas, M.; Petric, M.; Dutil, L.; Rahn, K.; Ludwig, K.; Arbus, G.S.; Michel, P.; Sherman, P.M.; Wilson, J.; et al. Age-Specific Frequencies of Antibodies to Escherichia coli Verocytotoxins (Shiga Toxins) 1 and 2 among Urban and Rural Populations in Southern Ontario. J. Infect. Dis. 2003, 188, 1724–1729.

- Kistemann, T.; Zimmer, S.; Vågsholm, I.; Andersson, Y. GIS-supported investigation of human EHEC and cattle VTEC O157 infections in Sweden: Geographical distribution, spatial variation and possible risk factors. Epidemiol. Infect. 2004, 132, 495–505.

- Griffin, P.M.; Tauxe, R.V. The Epidemiology of Infections Caused by Escherichia coli O157: H7, Other Enterohemorrhagic, E. coli, and the Associated Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome. Epidemiol. Rev. 1991, 13, 60–98.

- Nielsen, E.M.; Scheutz, F.; Torpdahl, M. Continuous Surveillance of Shiga Toxin–Producing Escherichia coli Infections by Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis Shows That Most Infections Are Sporadic. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2006, 3, 81–87.

- Grisaru, S.; Midgley, J.P.; Hamiwka, L.A.; Wade, A.W.; Samuel, S.M. Diarrhea-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome in southern Alberta: A long-term single-centre experience. Paediatr. Child Health 2011, 16, 337–340.

- Boerlin, P.; McEwen, S.A.; Boerlin-Petzold, F.; Wilson, J.B.; Johnson, R.P.; Gyles, C.L. Associations between virulence factors of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli and disease in humans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1999, 37, 497–503.

- Byrne, L.; Vanstone, G.L.; Perry, N.T.; Launders, N.; Adak, G.K.; Godbole, G.; Grant, K.A.; Smith, R.; Jenkins, C. Epidemiology and microbiology of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli other than serogroup O157 in England, 2009–2013. J. Med. Microbiol. 2014, 63, 1181–1188.

- Gould, L.H.; Mody, R.K.; Ong, K.L.; Clogher, P.; Cronquist, A.B.; Garman, K.N.; Lathrop, S.; Medus, C.; Spina, N.L.; Webb, T.H.; et al. Increased recognition of non-O157 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli infections in the United States during 2000-2010: Epidemiologic features and comparison with E. coli O157 infections. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2013, 10, 453–460.

- Hedican, E.B.; Medus, C.; Besser, J.M.; Juni, B.A.; Koziol, B.; Taylor, C.; Smith, K.E. Characteristics of O157 versus Non-O157 Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli Infections in Minnesota, 2000–2006. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 49, 358–364.

- Hadler, J.L.; Clogher, P.; Hurd, S.; Phan, Q.; Mandour, M.; Bemis, K.; Marcus, R. Ten-Year Trends and Risk Factors for Non-O157 Shiga Toxin–Producing Escherichia coli Found Through Shiga Toxin Testing, Connecticut, 2000–2009. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 53, 269–276.

- Ostroff, S.M.; Tarr, P.I.; Neill, M.A.; Lewis, J.H.; Hargrett-Bean, N.; Kobayashi, J.M. Toxin genotypes and plasmid profiles as determinants of systemic sequelae in Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections. J. Infect. Dis. 1989, 160, 994–998.

- Matussek, A.; Einemo, I.-M.; Jogenfors, A.; Löfdahl, S.; Löfgren, S. Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli in Diarrheal Stool of Swedish Children: Evaluation of Polymerase Chain Reaction Screening and Duration of Shiga Toxin Shedding. J. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. Soc. 2016, 5, 147–151.

- Manning, S.D.; Motiwala, A.S.; Springman, A.C.; Qi, W.; Lacher, D.W.; Ouellette, L.M.; Mladonicky, J.M.; Somsel, P.; Rudrik, J.T.; Dietrich, S.E.; et al. Variation in virulence among clades of Escherichia coli O157:H7 associated with disease outbreaks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 4868–4873.

- Dundas, S.; Todd, W.T.; Stewart, A.I.; Murdoch, P.S.; Chaudhuri, A.K.; Hutchinson, S.J. The central Scotland Escherichia coli O157:H7 outbreak: Risk factors for the hemolytic uremic syndrome and death among hospitalized patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2001, 33, 923–931.

- Gould, L.H.; Demma, L.; Jones, T.F.; Hurd, S.; Vugia, D.J.; Smith, K.; Shiferaw, B.; Segler, S.; Palmer, A.; Zansky, S.; et al. Hemolytic uremic syndrome and death in persons with Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection, foodborne diseases active surveillance network sites, 2000–2006. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 49, 1480–1485.

- Whitney, B.M.; Mainero, C.; Humes, E.; Hurd, S.; Niccolai, L.; Hadler, J.L. Socioeconomic Status and Foodborne Pathogens in Connecticut, USA, 2000–2011(1). Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015, 21, 1617–1624.

- Newburg, D.S.; Chaturvedi, P.; Lopez, E.L.; Devoto, S.; Fayad, A.; Cleary, T.G. Susceptibility to hemolytic-uremic syndrome relates to erythrocyte glycosphingolipid patterns. J. Infect. Dis. 1993, 168, 476–479.

- Watarai, S.; Yokota, K.; Kishimoto, T.; Kanadani, T.; Taketa, K.; Oguma, K. Relationship between susceptibility to hemolytic-uremic syndrome and levels of globotriaosylceramide in human sera. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001, 39, 798–800.

- Taranta, A.; Gianviti, A.; Palma, A.; De Luca, V.; Mannucci, L.; Procaccino, M.A.; Ghiggeri, G.M.; Caridi, G.; Fruci, D.; Ferracuti, S.; et al. Genetic risk factors in typical haemolytic uraemic syndrome. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2009, 24, 1851–1857.

- Fujii, Y.; Numata, S.; Nakamura, Y.; Honda, T.; Furukawa, K.; Urano, T.; Wiels, J.; Uchikawa, M.; Ozaki, N.; Matsuo, S.; et al. Murine glycosyltransferases responsible for the expression of globo-series glycolipids: cDNA structures, mRNA expression, and distribution of their products. Glycobiology 2005, 15, 1257–1267.

- Argyle, J.C.; Hogg, R.J.; Pysher, T.J.; Silva, F.G.; Siegler, R.L. A clinicopathological study of 24 children with hemolytic uremic syndrome. Pediatr. Nephrol. 1990, 4, 52–58.

- Inward, C.D.; Howie, A.J.; Fitzpatrick, M.M.; Rafaat, F.; Milford, D.V.; Taylor, C.M. Renal histopathology in fatal cases of diarrhoea-associated haemolytic uraemic syndrome. Pediatr. Nephrol. 1997, 11, 556–559.

- Keepers, T.R.; Psotka, M.A.; Gross, L.K.; Obrig, T.G. A Murine Model of HUS: Shiga Toxin with Lipopolysaccharide Mimics the Renal Damage and Physiologic Response of Human Disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2006, 17, 3404–3414.

- Keepers, T.R.; Gross, L.K.; Obrig, T.G. Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein 1, Macrophage Inflammatory Protein 1α, and RANTES Recruit Macrophages to the Kidney in a Mouse Model of Hemolytic-Uremic Syndrome. Infect. Immun. 2007, 75, 1229–1236.

- Roche, J.K.; Keepers, T.R.; Gross, L.K.; Seaner, R.M.; Obrig, T.G. CXCL1/KC and CXCL2/MIP-2 Are Critical Effectors and Potential Targets for Therapy of Escherichia coli O157:H7-Associated Renal Inflammation. Am. J. Pathol. 2007, 170, 526–537.

- Mayer, C.L.; Leibowitz, C.S.; Kurosawa, S.; Stearns-Kurosawa, D.J. Shiga toxins and the pathophysiology of hemolytic uremic syndrome in humans and animals. Toxins 2012, 4, 1261–1287.

- Mohawk, K.L.; O’Brien, A.D. Mouse models of Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection and shiga toxin injection. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2011, 2011, 258185.

- Proulx, F.; Seidman, E.; Mariscalco, M.M.; Lee, K.; Caroll, S. Increased Circulating Levels of Lipopolysaccharide Binding Protein in Children with Escherichia coli O157:H7 Hemorrhagic Colitis and Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 1999, 6, 773.

- Koster, F.; Levin, J.; Walker, L.; Tung, K.S.; Gilman, R.H.; Rahaman, M.M.; Majid, M.A.; Islam, S.; Williams, J.R. Hemolytic-uremic syndrome after shigellosis. Relation to endotoxemia and circulating immune complexes. N. Engl. J. Med. 1978, 298, 927–933.

- Dennhardt, S.; Pirschel, W.; Wissuwa, B.; Daniel, C.; Gunzer, F.; Lindig, S.; Medyukhina, A.; Kiehntopf, M.; Rudolph, W.W.; Zipfel, P.F.; et al. Modeling Hemolytic-Uremic Syndrome: In-Depth Characterization of Distinct Murine Models Reflecting Different Features of Human Disease. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9.

- Hews, C.L.; Tran, S.-L.; Wegmann, U.; Brett, B.; Walsham, A.D.S.; Kavanaugh, D.; Ward, N.J.; Juge, N.; Schüller, S. The StcE metalloprotease of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli reduces the inner mucus layer and promotes adherence to human colonic epithelium ex vivo. Cell. Microbiol. 2017, 19.

- Croxen, M.A.; Finlay, B.B. Molecular mechanisms of Escherichia coli pathogenicity. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010, 8, 26–38.

- McDaniel, T.K.; Jarvis, K.G.; Donnenberg, M.S.; Kaper, J.B. A genetic locus of enterocyte effacement conserved among diverse enterobacterial pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 1664–1668.

- Erdem, A.L.; Avelino, F.; Xicohtencatl-Cortes, J.; Girón, J.A. Host Protein Binding and Adhesive Properties of H6 and H7 Flagella of Attaching and Effacing Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 2007, 189, 7426–7435.

- Xicohtencatl-Cortes, J.; Monteiro-Neto, V.; Ledesma, M.A.; Jordan, D.M.; Francetic, O.; Kaper, J.B.; Puente, J.L.; Girón, J.A. Intestinal adherence associated with type IV pili of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 3519–3529.

- Robinson, C.M.; Sinclair, J.F.; Smith, M.J.; O’Brien, A.D. Shiga toxin of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli type O157:H7 promotes intestinal colonization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 9667–9672.

- Weiss, S.M.; Ladwein, M.; Schmidt, D.; Ehinger, J.; Lommel, S.; Städing, K.; Beutling, U.; Disanza, A.; Frank, R.; Jänsch, L.; et al. IRSp53 links the enterohemorrhagic E. coli effectors Tir and EspFU for actin pedestal formation. Cell Host Microbe 2009, 5, 244–258.

- Garmendia, J.; Phillips, A.D.; Carlier, M.-F.; Chong, Y.; Schüller, S.; Marches, O.; Dahan, S.; Oswald, E.; Shaw, R.K.; Knutton, S.; et al. TccP is an enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 type III effector protein that couples Tir to the actin-cytoskeleton. Cell Microbiol. 2004, 6, 1167–1183.

- Cheng, H.-C.; Skehan, B.M.; Campellone, K.G.; Leong, J.M.; Rosen, M.K. Structural mechanism of WASP activation by the enterohaemorrhagic E. coli effector EspF(U). Nature 2008, 454, 1009–1013.

- Kovbasnjuk, O.; Mourtazina, R.; Baibakov, B.; Wang, T.; Elowsky, C.; Choti, M.A.; Kane, A.; Donowitz, M. The glycosphingolipid globotriaosylceramide in the metastatic transformation of colon cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 19087–19092.

- Schüller, S.; Heuschkel, R.; Torrente, F.; Kaper, J.B.; Phillips, A.D. Shiga toxin binding in normal and inflamed human intestinal mucosa. Microbes Infect. 2007, 9, 35–39.

- Malyukova, I.; Murray, K.F.; Zhu, C.; Boedeker, E.; Kane, A.; Patterson, K.; Peterson, J.R.; Donowitz, M.; Kovbasnjuk, O. Macropinocytosis in Shiga toxin 1 uptake by human intestinal epithelial cells and transcellular transcytosis. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2009, 296, G78–G92.

- Schüller, S. Shiga Toxin Interaction with Human Intestinal Epithelium. Toxins 2011, 3, 626–639.

- Brigotti, M. The Interactions of Human Neutrophils with Shiga Toxins and Related Plant Toxins: Danger or Safety? Toxins 2012, 4, 157–190.

- Te Loo, D.M.; van Hinsbergh, V.W.; van den Heuvel, L.P.; Monnens, L.A. Detection of verocytotoxin bound to circulating polymorphonuclear leukocytes of patients with hemolytic uremic syndrome. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. JASN 2001, 12, 800–806.

- Brigotti, M.; Caprioli, A.; Tozzi, A.E.; Tazzari, P.L.; Ricci, F.; Conte, R.; Carnicelli, D.; Procaccino, M.A.; Minelli, F.; Ferretti, A.V.S.; et al. Shiga toxins present in the gut and in the polymorphonuclear leukocytes circulating in the blood of children with hemolytic-uremic syndrome. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2006, 44, 313–317.

- Geelen, J.M.; van der Velden, T.J.A.M.; Te Loo, D.M.W.M.; Boerman, O.C.; van den Heuvel, L.P.W.J.; Monnens, L.A.H. Lack of specific binding of Shiga-like toxin (verocytotoxin) and non-specific interaction of Shiga-like toxin 2 antibody with human polymorphonuclear leucocytes. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2007, 22, 749–755.

- Flagler, M.J.; Strasser, J.E.; Chalk, C.L.; Weiss, A.A. Comparative analysis of the abilities of Shiga toxins 1 and 2 to bind to and influence neutrophil apoptosis. Infect. Immun. 2007, 75, 760–765.

- Brigotti, M.; Carnicelli, D.; Ravanelli, E.; Barbieri, S.; Ricci, F.; Bontadini, A.; Tozzi, A.E.; Scavia, G.; Caprioli, A.; Tazzari, P.L.; et al. Interactions between Shiga toxins and human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2008, 84, 1019–1027.

- Richardson, S.E.; Rotman, T.A.; Jay, V.; Smith, C.R.; Becker, L.E.; Petric, M.; Olivieri, N.F.; Karmali, M.A. Experimental verocytotoxemia in rabbits. Infect. Immun. 1992, 60, 4154–4167.

- Brigotti, M.; Tazzari, P.L.; Ravanelli, E.; Carnicelli, D.; Rocchi, L.; Arfilli, V.; Scavia, G.; Minelli, F.; Ricci, F.; Pagliaro, P.; et al. Clinical relevance of shiga toxin concentrations in the blood of patients with hemolytic uremic syndrome. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2011, 30, 486–490.

- Obrig, T.G.; Louise, C.B.; Lingwood, C.A.; Boyd, B.; Barley-Maloney, L.; Daniel, T.O. Endothelial heterogeneity in Shiga toxin receptors and responses. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 15484–15488.

- Khan, F.; Proulx, F.; Lingwood, C.A. Detergent-resistant globotriaosyl ceramide may define verotoxin/glomeruli-restricted hemolytic uremic syndrome pathology. Kidney Int. 2009, 75, 1209–1216.

- Cooling, L.L.W.; Walker, K.E.; Gille, T.; Koerner, T.A.W. Shiga Toxin Binds Human Platelets via Globotriaosylceramide (Pk Antigen) and a Novel Platelet Glycosphingolipid. Infect. Immun. 1998, 66, 4355–4366.

- Mangeney, M.; Richard, Y.; Coulaud, D.; Tursz, T.; Wiels, J. CD77: An antigen of germinal center B cells entering apoptosis. Eur. J. Immunol. 1991, 21, 1131–1140.

- Obata, F.; Tohyama, K.; Bonev, A.D.; Kolling, G.L.; Keepers, T.R.; Gross, L.K.; Nelson, M.T.; Sato, S.; Obrig, T.G. Shiga Toxin 2 Affects the Central Nervous System through Receptor Globotriaosylceramide Localized to Neurons. J. Infect. Dis. 2008, 198, 1398–1406.

- Okuda, T.; Tokuda, N.; Numata, S.; Ito, M.; Ohta, M.; Kawamura, K.; Wiels, J.; Urano, T.; Tajima, O.; Furukawa, K.; et al. Targeted disruption of Gb3/CD77 synthase gene resulted in the complete deletion of globo-series glycosphingolipids and loss of sensitivity to verotoxins. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 10230–10235.

- Römer, W.; Berland, L.; Chambon, V.; Gaus, K.; Windschiegl, B.; Tenza, D.; Aly, M.R.E.; Fraisier, V.; Florent, J.-C.; Perrais, D.; et al. Shiga toxin induces tubular membrane invaginations for its uptake into cells. Nature 2007, 450, 670–675.

- Müthing, J.; Schweppe, C.H.; Karch, H.; Friedrich, A.W. Shiga toxins, glycosphingolipid diversity, and endothelial cell injury. Thromb. Haemost. 2009, 101, 252–264.

- Torgersen, M.L.; Lauvrak, S.U.; Sandvig, K. The A-subunit of surface-bound Shiga toxin stimulates clathrin-dependent uptake of the toxin. FEBS J. 2005, 272, 4103–4113.

- Villysson, A.; Tontanahal, A.; Karpman, D. Microvesicle Involvement in Shiga Toxin-Associated Infection. Toxins 2017, 9, 376.

- Johannes, L.; Parton, R.G.; Bassereau, P.; Mayor, S. Building endocytic pits without clathrin. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2015, 16, 311–321.

- Sandvig, K.; Garred, O.; Prydz, K.; Kozlov, J.V.; Hansen, S.H.; van Deurs, B. Retrograde transport of endocytosed Shiga toxin to the endoplasmic reticulum. Nature 1992, 358, 510–512.

- Garred, O.; Dubinina, E.; Polesskaya, A.; Olsnes, S.; Kozlov, J.; Sandvig, K. Role of the disulfide bond in Shiga toxin A-chain for toxin entry into cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 11414–11419.

- Endo, Y.; Tsurugi, K.; Yutsudo, T.; Takeda, Y.; Ogasawara, T.; Igarashi, K. Site of action of a Vero toxin (VT2) from Escherichia coli O157:H7 and of Shiga toxin on eukaryotic ribosomes. RNA N-glycosidase activity of the toxins. Eur. J. Biochem. 1988, 171, 45–50.

- Johannes, L.; Römer, W. Shiga toxins—From cell biology to biomedical applications. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010, 8, 105–116.

- Kavaliauskiene, S.; Dyve Lingelem, A.B.; Skotland, T.; Sandvig, K. Protection against Shiga Toxins. Toxins 2017, 9, 44.

- Mukhopadhyay, S.; Linstedt, A.D. Manganese Blocks Intracellular Trafficking of Shiga Toxin and Protects Against Shiga Toxicosis. Science 2012, 335, 332–335.

- Cherla, R.P.; Lee, S.Y.; Mees, P.L.; Tesh, V.L. Shiga toxin 1-induced cytokine production is mediated by MAP kinase pathways and translation initiation factor eIF4E in the macrophage-like THP-1 cell line. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2006, 79, 397–407.

- Jandhyala, D.M.; Ahluwalia, A.; Schimmel, J.J.; Rogers, A.B.; Leong, J.M.; Thorpe, C.M. Activation of the Classical Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases Is Part of the Shiga Toxin-Induced Ribotoxic Stress Response and Contribute to Shiga Toxin-Induced Inflammation. Infect. Immun. 2016, 84, 138–148.

- Tesh, V.L. Activation of cell stress response pathways by Shiga toxins. Cell Microbiol. 2011, 14, 1–9.

- Van Setten, P.A.; Monnens, L.A.; Verstraten, R.G.; van den Heuvel, L.P.; van Hinsbergh, V.W. Effects of verocytotoxin-1 on nonadherent human monocytes: Binding characteristics, protein synthesis, and induction of cytokine release. Blood 1996, 88, 174–183.

- Ramegowda, B.; Tesh, V.L. Differentiation-associated toxin receptor modulation, cytokine production, and sensitivity to Shiga-like toxins in human monocytes and monocytic cell lines. Infect. Immun. 1996, 64, 1173–1180.

- Falguières, T.; Mallard, F.; Baron, C.; Hanau, D.; Lingwood, C.; Goud, B.; Salamero, J.; Johannes, L. Targeting of Shiga toxin B-subunit to retrograde transport route in association with detergent-resistant membranes. Mol. Biol. Cell 2001, 12, 2453–2468.

- Eisenhauer, P.B.; Chaturvedi, P.; Fine, R.E.; Ritchie, A.J.; Pober, J.S.; Cleary, T.G.; Newburg, D.S. Tumor necrosis factor alpha increases human cerebral endothelial cell Gb3 and sensitivity to Shiga toxin. Infect. Immun. 2001, 69, 1889–1894.

- Stricklett, P.K.; Hughes, A.K.; Kohan, D.E. Inhibition of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase ameliorates cytokine up-regulated shigatoxin-1 toxicity in human brain microvascular endothelial cells. J. Infect. Dis. 2005, 191, 461–471.

- Stone, M.K.; Kolling, G.L.; Lindner, M.H.; Obrig, T.G. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase mediates lipopolysaccharide and tumor necrosis factor alpha induction of shiga toxin 2 sensitivity in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Infect. Immun. 2008, 76, 1115–1121.

- Matussek, A.; Lauber, J.; Bergau, A.; Hansen, W.; Rohde, M.; Dittmar, K.E.J.; Gunzer, M.; Mengel, M.; Gatzlaff, P.; Hartmann, M.; et al. Molecular and functional analysis of Shiga toxin–induced response patterns in human vascular endothelial cells. Blood 2003, 102, 1323–1332.

- Lee, M.-S.; Koo, S.; Jeong, D.G.; Tesh, V.L. Shiga Toxins as Multi-Functional Proteins: Induction of Host Cellular Stress Responses, Role in Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Applications. Toxins 2016, 8, 77.

- Gobert, A.P.; Vareille, M.; Glasser, A.-L.; Hindré, T.; de Sablet, T.; Martin, C. Shiga toxin produced by enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli inhibits PI3K/NF-kappaB signaling pathway in globotriaosylceramide-3-negative human intestinal epithelial cells. J. Immunol. 2007, 178, 8168–8174.

- Sellier-Leclerc, A.-L.; Fremeaux-Bacchi, V.; Dragon-Durey, M.-A.; Macher, M.-A.; Niaudet, P.; Guest, G.; Boudailliez, B.; Bouissou, F.; Deschenes, G.; Gie, S.; et al. Differential impact of complement mutations on clinical characteristics in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. JASN 2007, 18, 2392–2400.

- Noris, M.; Caprioli, J.; Bresin, E.; Mossali, C.; Pianetti, G.; Gamba, S.; Daina, E.; Fenili, C.; Castelletti, F.; Sorosina, A.; et al. Relative role of genetic complement abnormalities in sporadic and familial aHUS and their impact on clinical phenotype. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. CJASN 2010, 5, 1844–1859.

- Frémeaux-Bacchi, V.; Miller, E.C.; Liszewski, M.K.; Strain, L.; Blouin, J.; Brown, A.L.; Moghal, N.; Kaplan, B.S.; Weiss, R.A.; Lhotta, K.; et al. Mutations in complement C3 predispose to development of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Blood 2008, 112, 4948–4952.

- Fremeaux-Bacchi, V.; Dragon-Durey, M.-A.; Blouin, J.; Vigneau, C.; Kuypers, D.; Boudailliez, B.; Loirat, C.; Rondeau, E.; Fridman, W.H. Complement factor I: A susceptibility gene for atypical haemolytic uraemic syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 2004, 41, e84.

- De Jorge, E.G.; Harris, C.L.; Esparza-Gordillo, J.; Carreras, L.; Arranz, E.A.; Garrido, C.A.; Lopez-Trascasa, M.; Sanchez-Corral, P.; Morgan, B.P.; de Cordoba, S.R.; et al. Gain-of-function mutations in complement factor B are associated with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 240–245.

- Dragon-Durey, M.-A.; Loirat, C.; Cloarec, S.; Macher, M.-A.; Blouin, J.; Nivet, H.; Weiss, L.; Fridman, W.H.; Frémeaux-Bacchi, V. Anti–Factor H Autoantibodies Associated with Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2005, 16, 555–563.

- Noris, M.; Remuzzi, G. Atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 1676–1687.

- Fakhouri, F.; Zuber, J.; Frémeaux-Bacchi, V.; Loirat, C. Haemolytic uraemic syndrome. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2017, 390, 681–696.

- Legendre, C.M.; Licht, C.; Muus, P.; Greenbaum, L.A.; Babu, S.; Bedrosian, C.; Bingham, C.; Cohen, D.J.; Delmas, Y.; Douglas, K.; et al. Terminal complement inhibitor eculizumab in atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 2169–2181.

- Licht, C.; Greenbaum, L.A.; Muus, P.; Babu, S.; Bedrosian, C.L.; Cohen, D.J.; Delmas, Y.; Douglas, K.; Furman, R.R.; Gaber, O.A.; et al. Efficacy and safety of eculizumab in atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome from 2-year extensions of phase 2 studies. Kidney Int. 2015, 87, 1061–1073.

- Fakhouri, F.; Hourmant, M.; Campistol, J.M.; Cataland, S.R.; Espinosa, M.; Gaber, A.O.; Menne, J.; Minetti, E.E.; Provôt, F.; Rondeau, E.; et al. Terminal Complement Inhibitor Eculizumab in Adult Patients With Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome: A Single-Arm, Open-Label Trial. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2016, 68, 84–93.

- Noris, M.; Mescia, F.; Remuzzi, G. STEC-HUS, atypical HUS and TTP are all diseases of complement activation. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2012, 8, 622–633.

- Thurman, J.M.; Marians, R.; Emlen, W.; Wood, S.; Smith, C.; Akana, H.; Holers, V.M.; Lesser, M.; Kline, M.; Hoffman, C.; et al. Alternative pathway of complement in children with diarrhea-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. CJASN 2009, 4, 1920–1924.

- Ståhl, A.; Sartz, L.; Karpman, D. Complement activation on platelet-leukocyte complexes and microparticles in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli-induced hemolytic uremic syndrome. Blood 2011, 117, 5503–5513.

- Ge, S.; Hertel, B.; Emden, S.H.; Beneke, J.; Menne, J.; Haller, H.; von Vietinghoff, S. Microparticle generation and leucocyte death in Shiga toxin-mediated HUS. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2012, 27, 2768–2775.

- Orth, D.; Khan, A.B.; Naim, A.; Grif, K.; Brockmeyer, J.; Karch, H.; Joannidis, M.; Clark, S.J.; Day, A.J.; Fidanzi, S.; et al. Shiga toxin activates complement and binds factor H: Evidence for an active role of complement in hemolytic uremic syndrome. J. Immunol. 2009, 182, 6394–6400.

- Poolpol, K.; Orth-Höller, D.; Speth, C.; Zipfel, P.F.; Skerka, C.; de Córdoba, S.R.; Brockmeyer, J.; Bielaszewska, M.; Würzner, R. Interaction of Shiga toxin 2 with complement regulators of the factor H protein family. Mol. Immunol. 2014, 58, 77–84.

- Morigi, M.; Galbusera, M.; Gastoldi, S.; Locatelli, M.; Buelli, S.; Pezzotta, A.; Pagani, C.; Noris, M.; Gobbi, M.; Stravalaci, M.; et al. Alternative pathway activation of complement by Shiga toxin promotes exuberant C3a formation that triggers microvascular thrombosis. J. Immunol. 2011, 187, 172–180.

- Westra, D.; Volokhina, E.B.; van der Molen, R.G.; van der Velden, T.J.A.M.; Jeronimus-Klaasen, A.; Goertz, J.; Gracchi, V.; Dorresteijn, E.M.; Bouts, A.H.M.; Keijzer-Veen, M.G.; et al. Serological and genetic complement alterations in infection-induced and complement-mediated hemolytic uremic syndrome. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2017, 32, 297–309.

- Lee, B.C.; Mayer, C.L.; Leibowitz, C.S.; Stearns-Kurosawa, D.J.; Kurosawa, S. Quiescent complement in nonhuman primates during E coli Shiga toxin-induced hemolytic uremic syndrome and thrombotic microangiopathy. Blood 2013, 122, 803–806.

- Porubsky, S.; Federico, G.; Müthing, J.; Jennemann, R.; Gretz, N.; Büttner, S.; Obermüller, N.; Jung, O.; Hauser, I.A.; Gröne, E.; et al. Direct acute tubular damage contributes to Shigatoxin-mediated kidney failure. J. Pathol. 2014, 234, 120–133.

- Zoja, C.; Locatelli, M.; Pagani, C.; Corna, D.; Zanchi, C.; Isermann, B.; Remuzzi, G.; Conway, E.M.; Noris, M. Lack of the lectin-like domain of thrombomodulin worsens Shiga toxin-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome in mice. J. Immunol. 2012, 189, 3661–3668.

- Delvaeye, M.; Noris, M.; De Vriese, A.; Esmon, C.T.; Esmon, N.L.; Ferrell, G.; Del-Favero, J.; Plaisance, S.; Claes, B.; Lambrechts, D.; et al. Thrombomodulin mutations in atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 345–357.

- Vincent, J.L.; Francois, B.; Zabolotskikh, I.; Daga, M.K.; Lascarrou, J.B.; Kirov, M.Y.; Pettilä, V.; Wittebole, X.; Meziani, F.; Mercier, E.; et al. Effect of a Recombinant Human Soluble Thrombomodulin on Mortality in Patients With Sepsis-Associated Coagulopathy: The SCARLET Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2019, 321, 1993–2002.

- Honda, T.; Ogata, S.; Mineo, E.; Nagamori, Y.; Nakamura, S.; Bando, Y.; Ishii, M. A novel strategy for hemolytic uremic syndrome: Successful treatment with thrombomodulin α. Pediatrics 2013, 131, e928–e933.

- Hughes, A.K.; Ergonul, Z.; Stricklett, P.K.; Kohan, D.E. Molecular Basis for High Renal Cell Sensitivity to the Cytotoxic Effects of Shigatoxin-1: Upregulation of Globotriaosylceramide Expression. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2002, 13, 2239–2245.

- Zoja, C.; Buelli, S.; Morigi, M. Shiga toxin-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome: Pathophysiology of endothelial dysfunction. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2010, 25, 2231–2240.

- Petruzziello-Pellegrini, T.N.; Moslemi-Naeini, M.; Marsden, P.A. New insights into Shiga toxin-mediated endothelial dysfunction in hemolytic uremic syndrome. Virulence 2013, 4, 556–563.

- Chandler, W.L.; Jelacic, S.; Boster, D.R.; Ciol, M.A.; Williams, G.D.; Watkins, S.L.; Igarashi, T.; Tarr, P.I. Prothrombotic coagulation abnormalities preceding the hemolytic-uremic syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 346, 23–32.

- Goldberg, R.J.; Nakagawa, T.; Johnson, R.J.; Thurman, J.M. The role of endothelial cell injury in thrombotic microangiopathy. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2010, 56, 1168–1174.

- Petruzziello-Pellegrini, T.N.; Yuen, D.A.; Page, A.V.; Patel, S.; Soltyk, A.M.; Matouk, C.C.; Wong, D.K.; Turgeon, P.J.; Fish, J.E.; Ho, J.J.D.; et al. The CXCR4/CXCR7/SDF-1 pathway contributes to the pathogenesis of Shiga toxin-associated hemolytic uremic syndrome in humans and mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 759–776.

- Nestoridi, E.; Tsukurov, O.; Kushak, R.I.; Ingelfinger, J.R.; Grabowski, E.F. Shiga toxin enhances functional tissue factor on human glomerular endothelial cells: Implications for the pathophysiology of hemolytic uremic syndrome*. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2005, 3, 752–762.

- Huang, J.; Haberichter, S.L.; Sadler, J.E. The B subunits of Shiga-like toxins induce regulated VWF secretion in a phospholipase D1-dependent manner. Blood 2012, 120, 1143–1149.

- Liu, F.; Huang, J.; Sadler, J.E. Shiga toxin (Stx)1B and Stx2B induce von Willebrand factor secretion from human umbilical vein endothelial cells through different signaling pathways. Blood 2011, 118, 3392–3398.

- Karpman, D.; Papadopoulou, D.; Nilsson, K.; Sjögren, A.C.; Mikaelsson, C.; Lethagen, S. Platelet activation by Shiga toxin and circulatory factors as a pathogenetic mechanism in the hemolytic uremic syndrome. Blood 2001, 97, 3100–3108.

- Morigi, M.; Micheletti, G.; Figliuzzi, M.; Imberti, B.; Karmali, M.A.; Remuzzi, A.; Remuzzi, G.; Zoja, C. Verotoxin-1 promotes leukocyte adhesion to cultured endothelial cells under physiologic flow conditions. Blood 1995, 86, 4553–4558.

- Zoja, C.; Angioletti, S.; Donadelli, R.; Zanchi, C.; Tomasoni, S.; Binda, E.; Imberti, B.; te Loo, M.; Monnens, L.; Remuzzi, G.; et al. Shiga toxin-2 triggers endothelial leukocyte adhesion and transmigration via NF-kappaB dependent up-regulation of IL-8 and MCP-1. Kidney Int. 2002, 62, 846–856.

- Pijpers, A.H.; van Setten, P.A.; van den Heuvel, L.P.; Assmann, K.J.; Dijkman, H.B.; Pennings, A.H.; Monnens, L.A.; van Hinsbergh, V.W. Verocytotoxin-induced apoptosis of human microvascular endothelial cells. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. JASN 2001, 12, 767–778.

- Karpman, D.; Håkansson, A.; Perez, M.T.; Isaksson, C.; Carlemalm, E.; Caprioli, A.; Svanborg, C. Apoptosis of renal cortical cells in the hemolytic-uremic syndrome: In vivo and in vitro studies. Infect. Immun. 1998, 66, 636–644.

- Owens, A.P.; Mackman, N. Tissue factor and thrombosis: The clot starts here. Thromb. Haemost. 2010, 104, 432–439.

- Arvidsson, I.; Ståhl, A.-L.; Hedström, M.M.; Kristoffersson, A.-C.; Rylander, C.; Westman, J.S.; Storry, J.R.; Olsson, M.L.; Karpman, D. Shiga toxin-induced complement-mediated hemolysis and release of complement-coated red blood cell-derived microvesicles in hemolytic uremic syndrome. J. Immunol. 2015, 194, 2309–2318.