Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Roberto Sorrentino and Version 2 by Vivi Li.

Dental professionals and patients are exposed to a high risk of COVID-19 infection, particularly in the prosthodontic practice, because of the bio-aerosol produced during teeth preparation with dental handpieces and the strict contact with oral fluids during impression making.

- coronavirus

- COVID-19

- SARS-CoV-2

- prosthodontics

- airborne

- dental impression

- pandemic

- prevention

1. Introduction

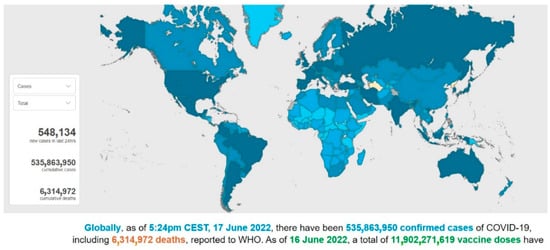

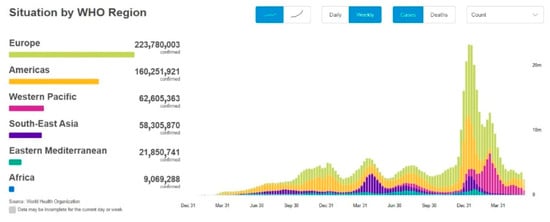

In December 2019, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), was first reported in Wuhan, Hubei province (China), and rapidly spread over 24 countries, leading the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare this severe pneumonia a global emergency on 30 January 2020 [1]. From 31 December 2019 to 17 June 2022, over 535,863,000 confirmed cases of coronavirus infectious disease-19 (COVID-19) have been reported, including approximately 6,315,000 deaths, and these numbers are increasing daily (Figure 1 and Figure 2) [2].

Figure 1. A screenshot of the interactive dashboard of COVID-19 global cases by the World Health Organization. This dashboard is continually updated and can be accessed at https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 17 June 2022).

Figure 2. A screenshot of the COVID-19 situation by WHO Region. This dashboard is continually updated and can be accessed at https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 17 June 2022).

SARS-CoV-2, of the family Coronaviridae, is a single-stranded RNA beta coronavirus that is characterized by a diameter of 50–200 nm and probably originated from bats and pangolins [3]. It shares 85–92% nucleotide sequence homology with the pangolin coronavirus (CoV) genome and 96.2% nucleotide homology with bat CoV RaTG13, confirming the zoonotic origin of the virus [4]. The animal-to-human transmission event, the spillover phenomenon of SARS-CoV-2, can be plausibly imputed to the sale and killing of wildlife species at the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, where the initial cases of COVID-19 emerged [4]. The comprehension of the initial dynamics of the infection and the identification of the animal source of SARS-CoV-2 would help to prevent future new zoonosis by strengthening the control of food and hygiene within live animal markets.

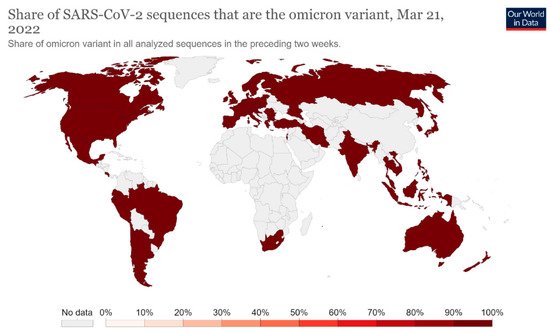

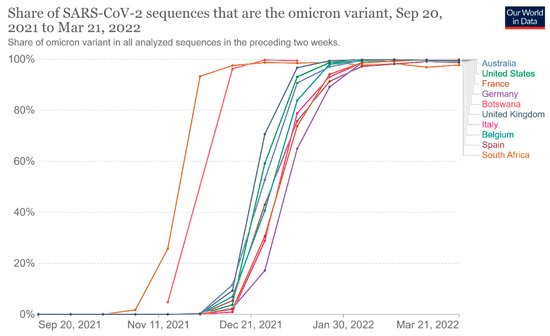

Since the first COVID-19 infection, some variants of SARS-CoV-2 have been found [5]. These variants are adaptive mutations in the viral genome that can alter the virus’s pathogenic potential, and some of them were classified as variants of concern (VOCs) due to their public health implications [5][6][5,6]. In particular, VOCs have been associated with increased virulence or transmissibility, decreased neutralization by antibodies acquired through vaccination or natural infection, the ability to elude detection, and a reduction in therapeutic or vaccine efficiency [6]. Five SARS-CoV-2 VOCs have been recognized according to the WHO: Alpha (B.1.1.7, first report in the United Kingdom); Beta (B.1.351, first report in South Africa); Gamma (P.1, first report in Brazil); Delta (B.1.617.2, first report in India); and Omicron (B.1.1.529, first report in South Africa) [6]. Among the listed VOCs, the Omicron variant is the most severely altered, paving the path for increased transmissibility and partial resistance to COVID-19 vaccine-induced immunity (Figure 3 and Figure 4) [5][7][8][5,7,8].

Figure 3. Share of SARS-CoV-2 sequences that are the omicron variant. This dashboard is continually updated and can be accessed at https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/covid-cases-omicron?country=GBR~FRA~BEL~DEU~ITA~ESP~USA~ZAF~BWA~AUS (accessed on 17 June 2022).

Figure 4. Share of omicron variant in all analyzed sequences. This dashboard is continually updated and can be accessed at https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/covid-cases-omicron?tab=chart&country=GBR~FRA~BEL~DEU~ITA~ESP~USA~ZAF~BWA~AUS (accessed on 17 June 2022).

The time from the infection to the onset of symptoms can vary from 2 to 14 days, and the median incubation period reported by the WHO was 5–6 days [9][10][9,10].

Older age and other risk factors, such as a history of underlying diseases and/or co-infections, play an important role in determining the severity of symptoms, leading to a higher risk to develop severe illness and death [11].

The clinical initial manifestations of COVID-19 can be aspecific. First of all, a large number of patients show symptoms of common cold, such as dry cough, sore throat, low-grade fever, or myalgia [11]. Less frequent manifestations of the infection may be nausea, diarrhea, dysgeusia, and persistent olfactory dysfunction (hyposmia) due to mucosal edema and nasal inflammation [12][13][12,13]. Some findings underlined the potential transmission of SARS-CoV-2 mediated by asymptomatic subjects, who may represent potential reservoirs for the spreading and re-emergence of the infection since the viral load in such patients was comparable to that of symptomatic patients [14].

Even if the mechanism of SARS-CoV-2 infection is not yet completely known, the high transmissibility of the virus can be partially explained by the higher affinity of the virus for cells located in the lower airways, where the virus binds using the host receptor for the conversion enzyme of angiotensin 2 (ACE2) and replicates, causing pneumonia [15].

The radiologic signs of bilateral pneumonia are abnormal ground-glass opacities found in chest X-ray and computed tomographic (CT) scans. The worst clinical picture patients can present is multiorgan dysfunction, acute renal failure, and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [16].

People older than 60 years old and patients with chronic comorbidities (especially diabetes, high blood pressure, and cardiovascular diseases) were found to be more prone to develop severe clinical disease and fatal outcomes, which occurred only in critical cases. Fortunately, children often seem to show mild symptoms of COVID-19 [15].

SARS-CoV-2 has a human-to-human typical transmission by means of respiratory droplets and indirect contact, whereas the conjunctival and mother-to-fetus modes still need to be confirmed [17].

Some evidence suggested that infected individuals can spread infection through bodily secretions, such as the saliva and nasal fluid produced by talking, sneezing, and coughing. The high presence of the virus in saliva may be explained by the binding of SARS-CoV-2 with ACE2 receptors, which are highly concentrated in salivary glands [18][19][20][18,19,20].

Moreover, the contact of contaminated hands with the mucous membranes of the mouth and/or nose may lead to the onset of COVID-19 infection. The fecal–oral mode also may be another important route for nosocomial spread. Consequently, the disinfection of objects, handwashing, and social distancing (beyond six feet) are strongly recommended in order to control the community outbreak of the disease [17][18][19][20][17,18,19,20].

In particular, dental offices could be easily contaminated since the use of high-speed handpieces or ultrasonic instruments could cause the aerosolization of patients’ secretions, such as saliva or blood. Thus, dental professionals are exposed to a high risk of contracting SARS-CoV-2 because social distancing is unachievable during dental procedures [21].

On the other hand, the increased susceptibility of patients in dental offices is another important concern: elderly age, diabetes, chemotherapy, pregnancy, or conditions of an impaired immune defense system may easily lead to a worsening clinical picture or fatal outcome in the case of SARS-CoV-2 infection [11][22][11,22].

Among the branches of dentistry, prosthodontics is the part of restorative dentistry concerned with the design, manufacture, and fitting of artificial replacements for missing teeth and the associated soft tissues. Many aspects and devices used during prosthetic procedures may offer the opportunity for cross-contamination, requiring careful attention and rigorous protocols for the prevention of infection spreading.

To date, there are scarce data in the scientific literature about the management of COVID-19 infection during prosthodontics procedures in order to prevent COVID-19 cross-infections.

2. Dental Impression

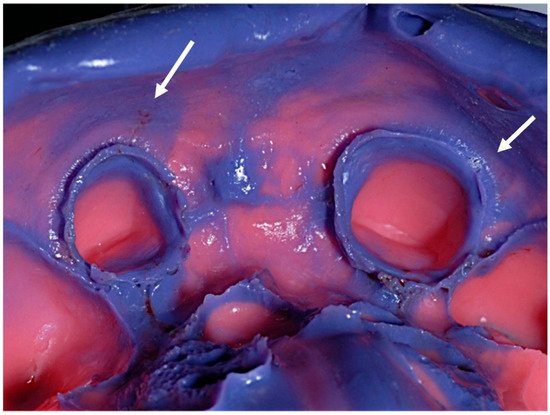

Dental impression and wax or silicone interocclusal records could be contaminated with patients’ saliva and, just as frequently, blood (Figure 56).

Figure 56.

Debris of saliva and blood on a conventional elastomeric dental impression (arrows indicated).