The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) is a ligand-activated transcription factor necessary for the launch of transcriptional responses important in health and disease. Its partner protein aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT), and AhR repressor protein (AhRR) are members of a family of structurally related transcription factors (basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH) motif-containing Per–ARNT–Sim (PAS), whose members carry out critical functions in the gene expression networks that underlie many physiological and developmental processes, especially those participating in responses to signals from the environment.

- reactive oxygen species

- oxidative stress

- antioxidant

- aryl hydrocarbon receptor

- AhR

- nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2

- Nrf2

1. Introduction

2. AhR

The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), its partner protein aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT), and AhR repressor protein (AhRR) are members of a family of structurally related transcription factors (basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH) motif-containing Per–ARNT–Sim (PAS), whose members carry out critical functions in the gene expression networks that underlie many physiological and developmental processes, especially those participating in responses to signals from the environment [20][21].

AhR is a unique and versatile biological sensor of planar chemical compounds of endogenous and exogenous origin [22][23] and is the only member of the PAS family that binds naturally occurring xenobiotics [24]. By functioning as a transcription factor, AhR takes part in many physiological and pathological processes in cells and tissues.

3. AhR Regulates Enzyme Systems Generating Reactive Oxygen Species

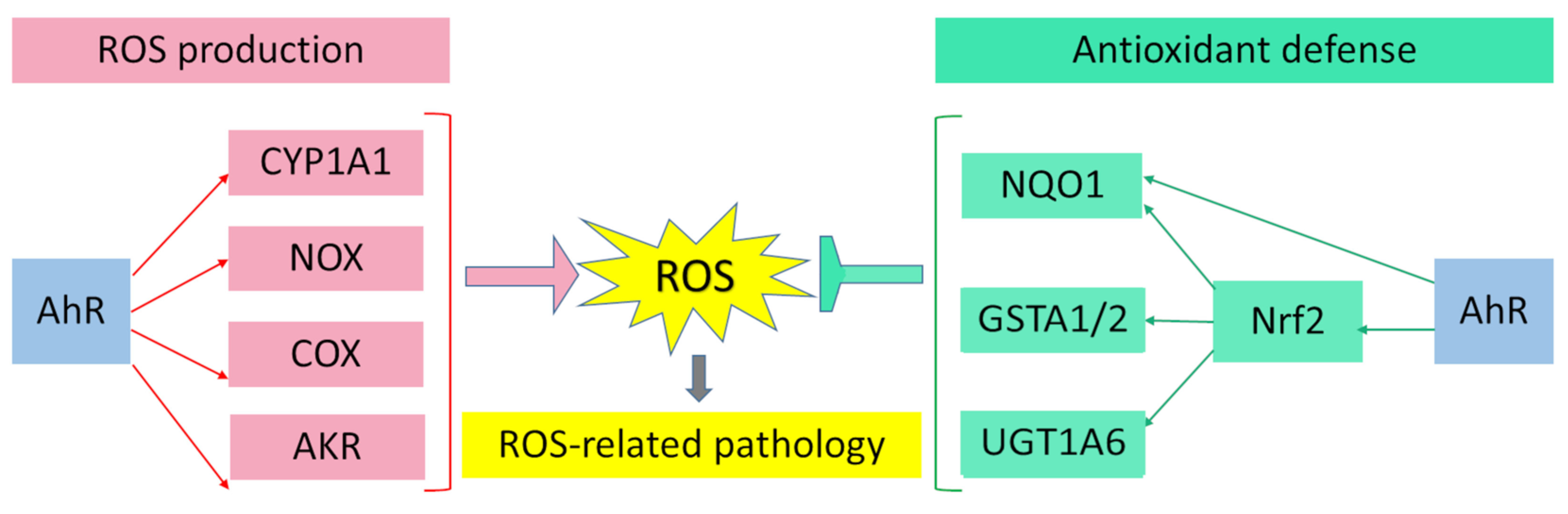

AhR is reported to be responsible for the toxic cellular effects of TCDD via pro-oxidant mechanisms [25][26]. There is convincing evidence that the activation of AhR-dependent detoxification of such environmental stressors as TCDD, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, polychlorinated biphenyls, and effects of ultraviolet radiation gives rise to oxidative stress and to the production of reactive oxygen species, thus inducing oxidative damage to DNA, lipids, and other cellular macromolecules [27][28][29][30]. Several enzyme systems, including CYP1A, NOX, COX, and possibly aldo–keto reductase (AKR) 1, are regulated through the AhR signaling pathway in terms of their ability to generate reactive oxygen species in various cell types and tissues [31][32][33][34].

4. Participation of AhR in Antioxidant Defense

5. AhR in the Pathogenesis of Diseases Related to Oxidative Stress

6. Conclusions

Figure 1. Pro-oxidant and antioxidant effects of AhR results in wide range of physiological and pathological processes in cells and tissues.

Figure 1. Pro-oxidant and antioxidant effects of AhR results in wide range of physiological and pathological processes in cells and tissues.References

- Pierre, S.; Chevallier, A.; Teixeira-Clerc, F.; Ambolet-Camoit, A.; Bui, L.C.; Bats, A.S.; Fournet, J.C.; Fernandez-Salguero, P.; Aggerbeck, M.; Lotersztajn, S.; et al. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor-dependent induction of liver fibrosis by dioxin. Toxicol. Sci. 2014, 137, 114–124.

- Kalkhof, S.; Dautel, F.; Loguercio, S.; Baumann, S.; Trump, S.; Jungnickel, H.; Otto, W.; Rudzok, S.; Potratz, S.; Luch, A.; et al. Pathway and time-resolved benzopyrene toxicity on Hepa1c1c7 cells at toxic and subtoxic exposure. J. Proteome Res. 2015, 14, 164–182.

- Esser, C.; Bargen, I.; Weighardt, H.; Haarmann-Stemmann, T.; Krutmann, J. Functions of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor in the skin. Semin. Immunopathol. 2013, 35, 677–691.

- Peng, F.; Xue, C.H.; Hwang, S.K.; Li, W.H.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, J.Z. Exposure to fine particulate matter associated with senile lentigo in Chinese women: A cross-sectional study. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol 2017, 31, 355–360.

- Guo, Y.L.; Yu, M.L.; Hsu, C.C.; Rogan, W.J. Chloracne, goiter, arthritis, and anemia after polychlorinated biphenyl poisoning: 14-year follow-Up of the Taiwan Yucheng cohort. Environ. Health Perspect. 1999, 107, 715–719.

- Caputo, R.; Monti, M.; Ermacora, E.; Carminati, G.; Gelmetti, C.; Gianotti, R.; Gianni, E.; Puccinelli, V. Cutaneous manifestations of tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin in children and adolescents. Follow-up 10 years after the Seveso, Italy, accident. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1988, 19, 812–819.

- Furue, M.; Uenotsuchi, T.; Urabe, K.; Ishikawa, T.; Kuwabara, M. Overview of Yusho. J. Dermatol. Sci. Suppl. 2005, 1, S3–S10.

- Mitoma, C.; Mine, Y.; Utani, A.; Imafuku, S.; Muto, M.; Akimoto, T.; Kanekura, T.; Furue, M.; Uchi, H. Current skin symptoms of Yusho patients exposed to high levels of 2,3,4,7,8-pentachlorinated dibenzofuran and polychlorinated biphenyls in 1968. Chemosphere 2015, 137, 45–51.

- Hu, T.; Pan, Z.; Yu, Q.; Mo, X.; Song, N.; Yan, M.; Zouboulis, C.C.; Xia, L.; Ju, Q. Benzo(a)pyrene induces interleukin (IL)-6 production and reduces lipid synthesis in human SZ95 sebocytes via the aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling pathway. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2016, 43, 54–60.

- Sun, Y.V.; Boverhof, D.R.; Burgoon, L.D.; Fielden, M.R.; Zacharewski, T.R. Comparative analysis of dioxin response elements in human, mouse and rat genomic sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 4512–4523.

- Hidaka, T.; Ogawa, E.; Kobayashi, E.H.; Suzuki, T.; Funayama, R.; Nagashima, T.; Fujimura, T.; Aiba, S.; Nakayama, K.; Okuyama, R.; et al. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor AhR links atopic dermatitis and air pollution via induction of the neurotrophic factor artemin. Nat. Immunol. 2017, 18, 64–73.

- Schallreuter, K.U.; Salem, M.A.; Gibbons, N.C.; Maitland, D.J.; Marsch, E.; Elwary, S.M.; Healey, A.R. Blunted epidermal L-tryptophan metabolism in vitiligo affects immune response and ROS scavenging by Fenton chemistry, part 2: Epidermal H2O2/ONOO(-)-mediated stress in vitiligo hampers indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated immune response signaling. FASEB J. 2012, 26, 2471–2485.

- van den Bogaard, E.H.; Bergboer, J.G.; Vonk-Bergers, M.; van Vlijmen-Willems, I.M.; Hato, S.V.; van der Valk, P.G.; Schroder, J.M.; Joosten, I.; Zeeuwen, P.L.; Schalkwijk, J. Coal tar induces AHR-dependent skin barrier repair in atopic dermatitis. J. Clin. Investig. 2013, 123, 917–927.

- Di Meglio, P.; Duarte, J.H.; Ahlfors, H.; Owens, N.D.; Li, Y.; Villanova, F.; Tosi, I.; Hirota, K.; Nestle, F.O.; Mrowietz, U.; et al. Activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor dampens the severity of inflammatory skin conditions. Immunity 2014, 40, 989–1001.

- Di Meglio, P.; Perera, G.K.; Nestle, F.O. The multitasking organ: Recent insights into skin immune function. Immunity 2011, 35, 857–869.

- Kostyuk, V.A.; Potapovich, A.I.; Lulli, D.; Stancato, A.; De Luca, C.; Pastore, S.; Korkina, L. Modulation of human keratinocyte responses to solar UV by plant polyphenols as a basis for chemoprevention of non-melanoma skin cancers. Curr. Med. Chem. 2013, 20, 869–879.

- Sheipouri, D.; Braidy, N.; Guillemin, G.J. Kynurenine Pathway in Skin Cells: Implications for UV-Induced Skin Damage. Int. J. Tryptophan Res. 2012, 5, 15–25.

- Droge, W. Free radicals in the physiological control of cell function. Physiol. Rev. 2002, 82, 47–95.

- Podkowinska, A.; Formanowicz, D. Chronic Kidney Disease as Oxidative Stress- and Inflammatory-Mediated Cardiovascular Disease. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 752.

- Mo, Y.; Lu, Z.; Wang, L.; Ji, C.; Zou, C.; Liu, X. The Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor in Chronic Kidney Disease: Friend or Foe? Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 589752.

- Liu, J.R.; Miao, H.; Deng, D.Q.; Vaziri, N.D.; Li, P.; Zhao, Y.Y. Gut microbiota-derived tryptophan metabolism mediates renal fibrosis by aryl hydrocarbon receptor signaling activation. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2021, 78, 909–922.

- Ichii, O.; Otsuka-Kanazawa, S.; Nakamura, T.; Ueno, M.; Kon, Y.; Chen, W.; Rosenberg, A.Z.; Kopp, J.B. Podocyte injury caused by indoxyl sulfate, a uremic toxin and aryl-hydrocarbon receptor ligand. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e108448.

- Ng, H.Y.; Yisireyili, M.; Saito, S.; Lee, C.T.; Adelibieke, Y.; Nishijima, F.; Niwa, T. Indoxyl sulfate downregulates expression of Mas receptor via OAT3/AhR/Stat3 pathway in proximal tubular cells. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e91517.

- Mutsaers, H.A.; Stribos, E.G.; Glorieux, G.; Vanholder, R.; Olinga, P. Chronic Kidney Disease and Fibrosis: The Role of Uremic Retention Solutes. Front. Med. 2015, 2, 60.

- Bahorun, T.; Soobrattee, M.A.; Luximon-Ramma, V.; Aruoma, O.I. Free Radicals and Antioxidants in Cardiovascular Health and Disease. Internet J. Med. Update. 2006, 1, 25–41.

- Quattrochi, L.C.; Tukey, R.H. Nuclear uptake of the Ah (dioxin) receptor in response to omeprazole: Transcriptional activation of the human CYP1A1 gene. Mol. Pharmacol. 1993, 43, 504–508.

- Ciolino, H.P.; Daschner, P.J.; Yeh, G.C. Dietary flavonols quercetin and kaempferol are ligands of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor that affect CYP1A1 transcription differentially. Biochem. J. 1999, 340 Pt 3, 715–722.

- Goya-Jorge, E.; Jorge Rodriguez, M.E.; Veitia, M.S.; Giner, R.M. Plant Occurring Flavonoids as Modulators of the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor. Molecules 2021, 26, 2315.

- Rothhammer, V.; Quintana, F.J. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor: An environmental sensor integrating immune responses in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 184–197.

- Hubbard, T.D.; Murray, I.A.; Perdew, G.H. Indole and Tryptophan Metabolism: Endogenous and Dietary Routes to Ah Receptor Activation. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2015, 43, 1522–1535.

- Phelan, D.; Winter, G.M.; Rogers, W.J.; Lam, J.C.; Denison, M.S. Activation of the Ah receptor signal transduction pathway by bilirubin and biliverdin. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1998, 357, 155–163.

- Larigot, L.; Juricek, L.; Dairou, J.; Coumoul, X. AhR signaling pathways and regulatory functions. Biochim. Open 2018, 7, 1–9.

- Schaldach, C.M.; Riby, J.; Bjeldanes, L.F. Lipoxin A4: A new class of ligand for the Ah receptor. Biochemistry 1999, 38, 7594–7600.

- Stejskalova, L.; Dvorak, Z.; Pavek, P. Endogenous and exogenous ligands of aryl hydrocarbon receptor: Current state of art. Curr. Drug Metab. 2011, 12, 198–212.

- Burczynski, M.E.; Lin, H.K.; Penning, T.M. Isoform-specific induction of a human aldo-keto reductase by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), electrophiles, and oxidative stress: Implications for the alternative pathway of PAH activation catalyzed by human dihydrodiol dehydrogenase. Cancer Res. 1999, 59, 607–614.

- Hockley, S.L.; Arlt, V.M.; Brewer, D.; Giddings, I.; Phillips, D.H. Time- and concentration-dependent changes in gene expression induced by benzo(a)pyrene in two human cell lines, MCF-7 and HepG2. BMC Genom. 2006, 7, 260.

- Yamashita, N.; Kanno, Y.; Saito, N.; Terai, K.; Sanada, N.; Kizu, R.; Hiruta, N.; Park, Y.; Bujo, H.; Nemoto, K. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor counteracts pharmacological efficacy of doxorubicin via enhanced AKR1C3 expression in triple negative breast cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 516, 693–698.

- Albertolle, M.E.; Guengerich, F.P. The relationships between cytochromes P450 and H2O2: Production, reaction, and inhibition. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2018, 186, 228–234.

- Valko, M.; Leibfritz, D.; Moncol, J.; Cronin, M.T.; Mazur, M.; Telser, J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2007, 39, 44–84.

- Veith, A.; Moorthy, B. Role of Cytochrome P450s in the Generation and Metabolism of Reactive Oxygen Species. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2018, 7, 44–51.

- Kuthan, H.; Ullrich, V. Oxidase and Oxygenase Function of the Microsomal Cytochrome-P450 Mono-Oxygenase System. Eur. J. Biochem. 1982, 126, 583–588.

- Kukielka, E.; Cederbaum, A.I. Nadph-Dependent and Nadh-Dependent Oxygen Radical Generation by Rat-Liver Nuclei in the Presence of Redox Cycling Agents and Iron. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1990, 283, 326–333.

- Hatherell, S.; Baltazar, M.T.; Reynolds, J.; Carmichael, P.L.; Dent, M.; Li, H.; Ryder, S.; White, A.; Walker, P.; Middleton, A.M. Identifying and Characterizing Stress Pathways of Concern for Consumer Safety in Next-Generation Risk Assessment. Toxicol. Sci. 2020, 176, 11–33.

- Wincent, E.; Bengtsson, J.; Bardbori, A.M.; Alsberg, T.; Luecke, S.; Rannug, U.; Rannug, A. Inhibition of cytochrome P4501-dependent clearance of the endogenous agonist FICZ as a mechanism for activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 4479–4484.

- Vogel, C.F.A.; Li, W.; Sciullo, E.; Newman, J.; Hammock, B.; Reader, J.R.; Tuscano, J.; Matsumura, F. Pathogenesis of aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated development of lymphoma is associated with increased cyclooxygenase-2 expression. Am. J. Pathol. 2007, 171, 1538–1548.

- Pathak, S.K.; Sharma, R.A.; Steward, W.P.; Mellon, J.K.; Griffiths, T.R.L.; Gescher, A.J. Oxidative stress and cyclooxygenase activity in prostate carcinogenesis: Targets for chemopreventive strategies. Eur. J. Cancer 2005, 41, 61–70.

- Vogel, C.; Boerboom, A.M.J.F.; Baechle, C.; El-Bahay, C.; Kahl, R.; Degen, G.H.; Abel, J. Regulation of prostaglandin endoperoxide H synthase-2 induction by dioxin in rat hepatocytes: Possible c-Src-mediated pathway. Carcinogenesis 2000, 21, 2267–2274.

- Fritsche, E.; Schafer, C.; Calles, C.; Bernsmann, T.; Bernshausen, T.; Wurm, M.; Hubenthal, U.; Cline, J.E.; Hajimiragha, H.; Schroeder, P.; et al. Lightening up the UV response by identification of the arylhydrocarbon receptor as a cytoplasmatic target for ultraviolet B radiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 8851–8856.

- Munoz, M.; Sanchez, A.; Martinez, M.P.; Benedito, S.; Lopez-Oliva, M.E.; Garcia-Sacristan, A.; Hernandez, M.; Prieto, D. COX-2 is involved in vascular oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction of renal interlobar arteries from obese Zucker rats. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 84, 77–90.

- Hernanz, R.; Briones, A.M.; Alonso, M.A.J.; Vila, E.; Salaices, M. Hypertension alters role of iNOS, COX-2, and oxidative stress in bradykinin relaxation impairment after LPS in rat cerebral arteries. Am. J. Physiol.-Circ. Physiol. 2004, 287, H225–H234.