The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) is a ligand-activated transcription factor necessary for the launch of transcriptional responses important in health and disease. Its partner protein aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT), and AhR repressor protein (AhRR) are members of a family of structurally related transcription factors (basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH) motif-containing Per–ARNT–Sim (PAS), whose members carry out critical functions in the gene expression networks that underlie many physiological and developmental processes, especially those participating in responses to signals from the environment.

- reactive oxygen species

- oxidative stress

- antioxidant

- aryl hydrocarbon receptor

- AhR

- nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2

- Nrf2

1. Introduction

-

Introduction

In live cells, reactive oxygen species are continuously generated, for example, by xanthine oxidase to degrade purine nucleotides, by nitric oxide synthase to form nitric oxide, and by other biochemical reactions as a byproduct of the oxidative energy metabolism for the formation of adenosine triphosphate from glucose in mitochondria [1-4].

Under normal physiological conditions, small amounts of oxygen are constantly converted into superoxide anions, hydrogen peroxide, and hydroxyl radicals. The biological activity of reactive oxygen species at a physiological concentration plays an important role in cell homeostasis and in a wide range of cellular parameters (proliferation, differentiation, cell cycle, and apoptosis) [5-8].

In the cell, reactive oxygen species arise under the influence of such exogenous pro-oxidant factors as environmental pollutants, ionizing and ultraviolet radiation, xenobiotics, air pollutants, and heavy metals [9, 10].

The main endogenous sites of production of cellular redox-reactive compounds include complexes I and III of the mitochondrial electron transport chain, endoplasmic reticulum, peroxisomes, and such enzymes as membrane-bound nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase (NOX) isoforms 1–5 (NOX1–NOX5), complexes of dual oxidases 1 and 2, xanthine oxidase, polyamine and amine oxidases, enzymes catabolizing lipids, and cytochrome P450 family 1 (CYP1A) [11-16].

The high reactivity of oxygen and its active species necessitates a multi-level antioxidant defense system that blocks the formation of highly active free radicals [10].

Free radicals are usually eliminated by the body’s natural antioxidant system. Redox homeostasis in normal cells is maintained by a nonenzymatic system consisting of carotenoids, flavonoids, glutathione, anserine, carnosine, homocarnosine, melatonin, thioredoxin, and vitamins C and E, as well as a network of antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutases, catalases, peroxiredoxins, glutathione peroxidase (GPX), glutaredoxins, and paraoxonases [17, 18]. In redox homeostasis, a certain role is played by the enzymes of phase II xenobiotic biotransformation, e.g., NADPH:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1), glutathione-S-transferase (GST) P1, GSTA1/2, UDP glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) 1A6, GPX4, and heme oxygenase 1 [19].

An imbalance between the formation of oxidative free radicals and the antioxidant defense capacity of the body’s cells is defined as oxidative stress. An important function in the regulation of oxidative stress is performed by the AhR signaling pathway via pro-oxidant and antioxidant mechanisms.

2. AhR

-

AhR

The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), its partner protein aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT), and AhR repressor protein (AhRR) are members of a family of structurally related transcription factors (basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH) motif-containing Per–ARNT–Sim (PAS), whose members carry out critical functions in the gene expression networks that underlie many physiological and developmental processes, especially those participating in responses to signals from the environment [20][21][20, 21].

AhR is a unique and versatile biological sensor of planar chemical compounds of endogenous and exogenous origin [22][23][22, 23] and is the only member of the PAS family that binds naturally occurring xenobiotics [24]. By functioning as a transcription factor, AhR takes part in many physiological and pathological processes in cells and tissues.

3. AhR Regulates Enzyme Systems Generating Reactive Oxygen Species

-

AhR Regulates Enzyme Systems Generating Reactive Oxygen Species

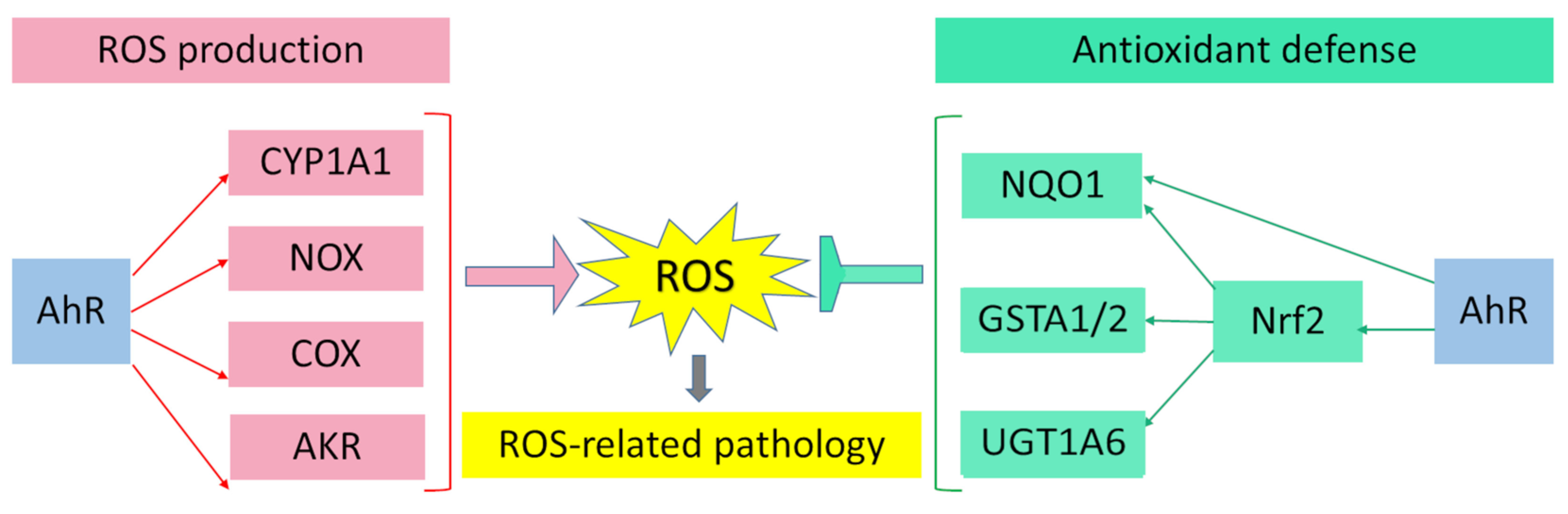

AhR is reported to be responsible for the toxic cellular effects of TCDD via pro-oxidant mechanisms [25][26][25, 26]. There is convincing evidence that the activation of AhR-dependent detoxification of such environmental stressors as TCDD, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, polychlorinated biphenyls, and effects of ultraviolet radiation gives rise to oxidative stress and to the production of reactive oxygen species, thus inducing oxidative damage to DNA, lipids, and other cellular macromolecules [27][28][29][30][27-30]. Several enzyme systems, including CYP1A, NOX, COX, and possibly aldo–keto reductase (AKR) 1, are regulated through the AhR signaling pathway in terms of their ability to generate reactive oxygen species in various cell types and tissues [31][32][33][34][31-34].

4. Participation of AhR in Antioxidant Defense

-

Participation of AhR in Antioxidant Defense

Aside from the AhR-dependent production of intracellular reactive oxygen species, the AhR signaling pathway modulates the expression of genes of the antioxidant system and thereby regulates cell functions that ensure protection from oxidative stress. Numerous studies indicate that the protective action of antioxidants against oxidative stress is mediated by AhR through a response to such AhR ligands as flavonoids, phytochemicals, and azoles [35-42].

When this type of ligand binds to AhR, the production of reactive oxygen species does not occur because of the induction of the nuclear translocation of AhR; instead, Nrf2 is activated. Nrf2 is a key biomolecule that provides cell protection against the oxidative damage caused by reactive oxygen species: Nrf2 is a transcription factor that regulates the genes encoding enzymes of the antioxidant system [43, 44].

5. AhR in the Pathogenesis of Diseases Related to Oxidative Stress

-

AhR in the Pathogenesis of Diseases Related to Oxidative Stress

Although initial studies on AhR were focused on its function as a signaling molecule of a chemical sensor responsive to environmental pollutants, lately, the range of subject areas has widened significantly. Our understanding has expanded regarding the role of the AhR signaling pathway in the regulation of a variety of physiological and pathological phenomena. AhR’s functions cover many cellular processes, including the regulation of cell survival, metabolic and protein homeostasis, inflammation, cell proliferation and differentiation, apoptosis, and cellular adhesion and migration. Reactive oxygen species-induced activation of transcription factors and proinflammatory genes increases inflammation. Accordingly, research on various diseases in which AhR induces an oxidative stress response—by switching on inflammation and antioxidant, prooxidant, and cytochrome P450 enzymes—is now within the scope of the interest of investigators.

It is known that oxidative stress causes inflammation and toxicity, and these problems can lead to such pathologies as cardiovascular, liver, kidney, lung, brain, eye, skin, and joint diseases, as well as aging and cancer [7, 45-49]. In recent decades, AhR has been increasingly recognized as an important modulator of disease because of AhR’s role in the regulation of the redox system and of immune and inflammatory responses [31, 50].

6. Conclusions

-

Conclusions

Major breakthroughs were recently made in the biology of redox modulation by AhR. Despite all the gained knowledge, the remaining intriguing questions concern the mechanism underlying the cell- and tissue-specific effects of AhR ligands and the dependence of responses on the type of ligands. The function of AhR is complicated because the outcome of its activation depends on a wide range of endogenous and exogenous ligands (which are characterized by different affinity values and diverse combinatorial effects) and on different AhR functions in many physiological and pathological processes in cells and tissues. The molecular mechanisms of AhR signaling and of the crosstalk between AhR signaling and other signal transduction cascades require further research. It is mostly the inconsistency of scientific findings that makes it difficult to determine the signaling pathways through which AhR can exert its beneficial or detrimental actions. There is growing evidence that AhR activation can have multidirectional effects on many aspects of human physiology and pathology, and that these may depend on cell and tissue types, or on the interaction of the AhR complex with non-traditional XRE sequences, or interaction with various coactivators and corepressors. Depending on many factors, the action of AhR agonists or antagonists can cause positive or negative effects on human health (Figure 4).

Figure 1. Pro-oxidant and antioxidant effects of AhR results in wide range of physiological and pathological processes in cells and tissues.

Figure 1. Pro-oxidant and antioxidant effects of AhR results in wide range of physiological and pathological processes in cells and tissues.The recognition that AhR is implicated in the pathogenesis of many human diseases has arisen in conjunction with numerous examples of diseases in which AhR modulates disease activity through interaction with environmental factors. The pathogenesis driven by AhR often includes oxidative stress and immune and inflammatory responses. The weight of evidence indicates that, in diseases of various organs and tissues, AhR activation can be beneficial or detrimental. The ultimate effect depends both on the context of the disease and on the nature of AhR ligands. In this context, AhR activation aggravates the symptoms of some diseases, but alleviates the symptoms of other diseases.

Currently, in the literature, there are few examples of disorders where the molecular mechanisms of AhR’s involvement in the pathogenesis are clear. More numerous are findings about various biological responses to the stimulation or inhibition of AhR in various diseases. At the current stage of our insight into AhR’s biology and its role in the pathogenesis of diverse diseases, the utility of AhR as a therapeutic target has already been established, and a foundation has been laid for the selection and design of effective AhR ligands as new treatments of various diseases. Although much basic research has been conducted on the functions of AhR in pathological processes, clinical studies about the effects on the mechanism of the AhR signaling pathway in different pathologies are still scarce, and further investigation is necessary.

-

References

- Chen, L., J.Y. Hu, and S.Q. Wang, The role of antioxidants in photoprotection: a critical review. J Am Acad Dermatol, 2012. 67(5): p. 1013-24.

- Murphy, M.P., How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem J, 2009. 417(1): p. 1-13.

- Cadenas, E., Mitochondrial free radical production and cell signaling. Mol Aspects Med, 2004. 25(1-2): p. 17-26.

- Di Meo, S., et al., Role of ROS and RNS Sources in Physiological and Pathological Conditions. Oxid Med Cell Longev, 2016. 2016: p. 1245049.

- Dandekar, A., R. Mendez, and K. Zhang, Cross talk between ER stress, oxidative stress, and inflammation in health and disease. Methods Mol Biol, 2015. 1292: p. 205-14.

- Finkel, T. and N.J. Holbrook, Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. Nature, 2000. 408(6809): p. 239-47.

- Reuter, S., et al., Oxidative stress, inflammation, and cancer: how are they linked? Free Radic Biol Med, 2010. 49(11): p. 1603-16.

- Haghi Aminjan, H., et al., Targeting of oxidative stress and inflammation through ROS/NF-kappaB pathway in phosphine-induced hepatotoxicity mitigation. Life Sci, 2019. 232: p. 116607.

- Sharifi-Rad, M., et al., Lifestyle, Oxidative Stress, and Antioxidants: Back and Forth in the Pathophysiology of Chronic Diseases. Front Physiol, 2020. 11: p. 694.

- Furue, M., et al., Antioxidants for Healthy Skin: The Emerging Role of Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptors and Nuclear Factor-Erythroid 2-Related Factor-2. Nutrients, 2017. 9(3).

- Rodriguez, R. and R. Redman, Balancing the generation and elimination of reactive oxygen species. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2005. 102(9): p. 3175-6.

- Curi, R., et al., Regulatory principles in metabolism-then and now. Biochem J, 2016. 473(13): p. 1845-57.

- Griendling, K.K., D. Sorescu, and M. Ushio-Fukai, NAD(P)H oxidase: role in cardiovascular biology and disease. Circ Res, 2000. 86(5): p. 494-501.

- To, E.E., et al., Endosomal NOX2 oxidase exacerbates virus pathogenicity and is a target for antiviral therapy. Nat Commun, 2017. 8(1): p. 69.

- Zangar, R.C., D.R. Davydov, and S. Verma, Mechanisms that regulate production of reactive oxygen species by cytochrome P450. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol, 2004. 199(3): p. 316-31.

- Agostinelli, E., et al., Potential anticancer application of polyamine oxidation products formed by amine oxidase: a new therapeutic approach. Amino Acids, 2010. 38(2): p. 353-68.

- Ng, M.P., et al., Does influenza A infection increase oxidative damage? Antioxid Redox Signal, 2014. 21(7): p. 1025-31.

- Masella, R., et al., Novel mechanisms of natural antioxidant compounds in biological systems: involvement of glutathione and glutathione-related enzymes. J Nutr Biochem, 2005. 16(10): p. 577-86.

- Gegotek, A. and E. Skrzydlewska, The role of transcription factor Nrf2 in skin cells metabolism. Arch Dermatol Res, 2015. 307(5): p. 385-96.

- McIntosh, B.E., J.B. Hogenesch, and C.A. Bradfield, Mammalian Per-Arnt-Sim proteins in environmental adaptation. Annu Rev Physiol, 2010. 72: p. 625-45.

- Nebert, D.W., Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR): "pioneer member" of the basic-helix/loop/helix per-Arnt-sim (bHLH/PAS) family of "sensors" of foreign and endogenous signals. Prog Lipid Res, 2017. 67: p. 38-57.

- Gargaro, M., et al., The Landscape of AhR Regulators and Coregulators to Fine-Tune AhR Functions. Int J Mol Sci, 2021. 22(2).

- Abel, J. and T. Haarmann-Stemmann, An introduction to the molecular basics of aryl hydrocarbon receptor biology. Biol Chem, 2010. 391(11): p. 1235-48.

- Hao, N. and M.L. Whitelaw, The emerging roles of AhR in physiology and immunity. Biochem Pharmacol, 2013. 86(5): p. 561-70.

- Esser, C., et al., Functions of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor in the skin. Seminars in Immunopathology, 2013. 35(6): p. 677-691.

- Denison, M.S., et al., Exactly the same but different: promiscuity and diversity in the molecular mechanisms of action of the aryl hydrocarbon (dioxin) receptor. Toxicol Sci, 2011. 124(1): p. 1-22.

- Dong, H., et al., Mutagenic potential of benzo[a] pyrene-derived DNA adducts positioned in codon 273 of the human P53 gene. Biochemistry, 2004. 43(50): p. 15922-15928.

- Landvik, N.E., et al., 3-Nitrobenzanthrone and 3-aminobenzanthrone induce DNA damage and cell signalling Hepa1c1c7 cells. Mutation Research-Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis, 2010. 684(1-2): p. 11-23.

- Phillips, T.D., et al., Mechanistic relationships between hepatic genotoxicity and carcinogenicity in male B6C3F1 mice treated with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon mixtures. Archives of Toxicology, 2015. 89(6): p. 967-977.

- Rossner, P., et al., Toxic Effects of the Major Components of Diesel Exhaust in Human Alveolar Basal Epithelial Cells (A549). International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2016. 17(9).

- Vogel, C.F.A., et al., The aryl hydrocarbon receptor as a target of environmental stressors - Implications for pollution mediated stress and inflammatory responses. Redox Biol, 2020. 34: p. 101530.

- Burczynski, M.E., H.K. Lin, and T.M. Penning, Isoform-specific induction of a human aldo-keto reductase by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), electrophiles, and oxidative stress: implications for the alternative pathway of PAH activation catalyzed by human dihydrodiol dehydrogenase. Cancer Res, 1999. 59(3): p. 607-14.

- Hockley, S.L., et al., Time- and concentration-dependent changes in gene expression induced by benzo(a)pyrene in two human cell lines, MCF-7 and HepG2. BMC Genomics, 2006. 7: p. 260.

- Yamashita, N., et al., Aryl hydrocarbon receptor counteracts pharmacological efficacy of doxorubicin via enhanced AKR1C3 expression in triple negative breast cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2019. 516(3): p. 693-698.

- Tsuji, G., et al., Identification of ketoconazole as an AhR-Nrf2 activator in cultured human keratinocytes: the basis of its anti-inflammatory effect. J Invest Dermatol, 2012. 132(1): p. 59-68.

- Takei, K., et al., Cynaropicrin attenuates UVB-induced oxidative stress via the AhR-Nrf2-Nqo1 pathway. Toxicol Lett, 2015. 234(2): p. 74-80.

- Takei, K., et al., Antioxidant soybean tar Glyteer rescues T-helper-mediated downregulation of filaggrin expression via aryl hydrocarbon receptor. J Dermatol, 2015. 42(2): p. 171-80.

- Nakahara, T., et al., Antioxidant Opuntia ficus-indica Extract Activates AHR-NRF2 Signaling and Upregulates Filaggrin and Loricrin Expression in Human Keratinocytes. J Med Food, 2015. 18(10): p. 1143-9.

- Haarmann-Stemmann, T., et al., The AhR-Nrf2 pathway in keratinocytes: on the road to chemoprevention? J Invest Dermatol, 2012. 132(1): p. 7-9.

- Jaiswal, A.K., Nrf2 signaling in coordinated activation of antioxidant gene expression. Free Radic Biol Med, 2004. 36(10): p. 1199-207.

- Niestroy, J., et al., Single and concerted effects of benzo[a]pyrene and flavonoids on the AhR and Nrf2-pathway in the human colon carcinoma cell line Caco-2. Toxicol In Vitro, 2011. 25(3): p. 671-83.

- Han, S.G., et al., EGCG protects endothelial cells against PCB 126-induced inflammation through inhibition of AhR and induction of Nrf2-regulated genes. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol, 2012. 261(2): p. 181-8.

- Yeager, R.L., et al., Introducing the "TCDD-inducible AhR-Nrf2 gene battery". Toxicol Sci, 2009. 111(2): p. 238-46.

- Tonelli, C., I.I.C. Chio, and D.A. Tuveson, Transcriptional Regulation by Nrf2. Antioxid Redox Signal, 2018. 29(17): p. 1727-1745.

- Hussain, T., et al., Oxidative Stress and Inflammation: What Polyphenols Can Do for Us? Oxid Med Cell Longev, 2016. 2016: p. 7432797.

- Yoshikawa T, N.Y., What Is Oxidative Stress? J. Japan Medical Association, 2002. 45(7): p. 271–276.

- Uttara, B., et al., Oxidative stress and neurodegenerative diseases: a review of upstream and downstream antioxidant therapeutic options. Curr Neuropharmacol, 2009. 7(1): p. 65-74.

- Pizzino, G., et al., Oxidative Stress: Harms and Benefits for Human Health. Oxid Med Cell Longev, 2017. 2017: p. 8416763.

- Pham-Huy, L.A., H. He, and C. Pham-Huy, Free radicals, antioxidants in disease and health. Int J Biomed Sci, 2008. 4(2): p. 89-96.

- Neavin, D.R., et al., The Role of the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor (AHR) in Immune and Inflammatory Diseases. Int J Mol Sci, 2018. 19(12).