Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Vivi Li and Version 3 by Vivi Li.

Interest in non-meat diets has been growing at an exponential rate in many countries. There is a wide consensus now that increased meat consumption is linked to higher health risks and environmental impact. Yet humans are social animals. Even the very personal decision of whether to eat meat or not is influenced by others around them. Researchers develop an agent-based model to study the effect of social influence on the spread of meat-eating behaviour in the British population.

- meat-eating behaviour

- vegetarianism

- social influence

- social interaction

- agent-based modelling

1. Background

The number of people who opt for a non-meat diet (including vegetarians and vegans) in the UK has been growing rapidly in recent years. A survey [1] shows that during the lockdown of COVID-19 in 2020, one in four people in the UK had reduced their consumption of animal products, and one in five had reduced their meat consumption. It is estimated that the number of vegans in the UK had quadrupled between 2014 and 2019 (Food and You Survey, 2014, Ipsos Mori surveys 2016, 2019). The rapid increase in the demand for meat substitutes has also created a new market with many business opportunities. In 2020 the global market for plant-based meat is estimated at USD 6.67 billion, with the U.S. market alone exceeding USD 1.4 billion.

People’s diets have a large impact on both their health and the environment [2], which are two of the grand challenges prioritised by the United Nations [3] and the UK government’s 25 Year Environment Plan [4]. Livestock is an important contributor to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, which account for 14.5% of all anthropogenic GHG emissions globally [5]. Annual emissions from beef production alone accounted for approximately 7% of total GHG emissions, according to the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). In addition, researchers find that foods associated with improved health also have low environmental impacts [2]. Increased meat consumption is found to be linked to the growth of degenerative disease (e.g., Alzheimer disease) [6], cancer [7][8], and stroke [9]. A more balanced and sustainable diet therefore will not only improve the quality of life and reduce national health care costs but also significantly lower the environmental impact of food consumption [10][11].

However, despite large public health campaigns and educational programmes to promote healthy eating, including more subtle approaches such as nudges, only modest effects have been achieved at best [12][13]. One reason is that these programmes tend to focus on raising awareness of the nutritional values and environmental impacts for individuals, while the choices of any individual are also influenced by their peers and the social context in which they interact [14][15][16]. Social factors such as gender, race, ethnicity, location of residence (region and urban vs. non-urban), and social class all appear to affect dietary habits even when controlling for physiological variables such as body weight and age [17]. To make public health campaigns and interventions more effective, it is important to go beyond conventional methods of information provision and awareness raising, and give more consideration to the influence of social interactions on these everyday decisions.

Humans are social animals. Apart from individual concerns for health, environmental impacts, and animal rights [18], one’s eating choices is also greatly influenced by their peers and social groups. A review of 69 experiments published between 1974 and 2014 found strong evidence for the role of social influence in one’s dietary choice and eating behaviour [19]. People tend to adjust their food choice and intake to affiliate with those around them such as parents, teachers, and peers [20][21]. Without realising it, people will mimic each other’s eating behaviour as a way to affiliate with and ingratiate others [22]. They will also unwittingly reduce the level of mimicry if they do not want to bond with the person they are eating with [23]. In a real-world setting, based on the combination of a field and a survey experiment in seven German university dining halls, [24] analysed the impact of social norms on meat consumption in a single meal choice situation, and found that direct normative influence leads to convergence towards vegetarian meal choices.

Importantly, many seemingly neutral lifestyle choices such as dietary choices are driven by underlying ideology or social status. DellaPosta, Shi [15] described the ‘latte-drinking liberals’ and ‘bird-hunting conservatives’ in the U.S., where the nonpartisan lifestyle choices of beverages and leisure activities are strongly associated with a distinctive political and ideological profile. People in the same network tend to become more similar in all aspects of life, not only in areas closely related to their ideological beliefs, thus leading to the clustering of lifestyles and choices [25]. According to Weber, a community of individuals with a shared ‘style of life’, agreed upon and expected from all those who belong in the group, marks the beginning of the forming of social status [26].

An increasingly important channel of peer influence is social media, which often leads to new lifestyle trends. Social media allows the sharing of information and opinions at a very personal level. For example, in the last few years, top influencers with millions of followers have started to share pictures and videos of their plant-based meals and recipes on various social media. It has been found that food pictures, personal blogs, and vlogs posted on social media are helpful in maintaining a plant-based diet [27]. As plant-based diets have become trendy on social media, their popularity has skyrocketed over the last few years, especially among young people [28]. As more generations grow up deeply engaged in social media, researchers can expect that peer influence will play an increasingly important role in shaping one’s lifestyle.

Whether in-person or online, peer influence is expected to be stronger if the peers are perceived to be ‘people like us’, which can happen on a variety of parameters (such as gender, race, body type, social class) [29]. Research has shown that social influence on eating behaviour is significantly enhanced if people are familiar with their eating companions, or if they perceive similarities with them in terms of gender, weight, or age [19][30][31]. Cruwys, Platow [32] found that when students have high levels of organisational identification with their university, they adjust their food intake to those from the same university, but not from a different one.

In addition, research found that people in different groups may differentiate from each other by abandoning a certain behaviour that is common in the other group [33]. For example, university students are found to consume less junk food if eating junk food is associated with an undesirable group [34]; minority participants are found to eat less healthily when healthy eating is perceived as the marker of the majority group [35].

Agent-based modelling (ABM) is a research method that simulates autonomous and interacting agents in a virtual environment on a computer. An advantage of ABM is that it explicitly represents the dynamic interactions among individuals. ABM has been used to simulate and understand the dynamics of social identity and to test the logical consequences of social theories [36][37][38]. It has also been applied in the areas of civil conflicts [39][40], crowd simulation [41], and natural resource management [42][43].

2. The Agent-Based Model of Social Influence and Meat-Eating Behaviour

2.1. Agent and Attributes

An agent in the model represents a person. Table 1 lists the attributes of a Person agent.Table 1. Main agent attributes.

| Attribute | Type/Value | Data Source | Endogenous? | Dynamic? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serial number | String | BSA | N | N |

| Age | integer | BSA | N | N |

| Region | 12 region in the UK | BSA | N | N |

| Gender | [Male, Female] | BSA | N | N |

| Social Class | [Manual, non-manual] | BSA | N | N |

| Political Party | [conservative, labour, libdem, ukip, green, other, none, dk] | BSA | N | N |

| Meat habit | [no meat, less meat, meat] | Initialised with BSA, updated each period | Y | Y |

| Change tendency * | between 0 and 1 | Heterogeneous parameter | N | N |

| Social accounting * | A list of three numbers between 0 and 1 for the three meat habits | Updated each period | Y | Y |

* more details below.

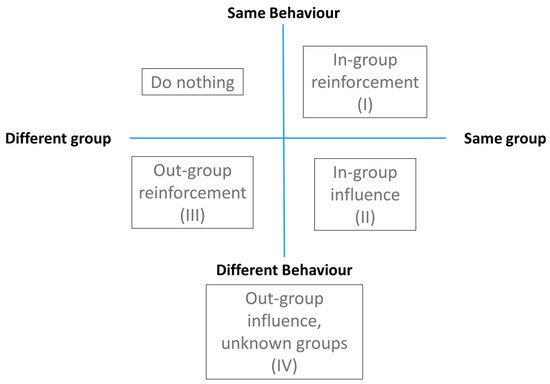

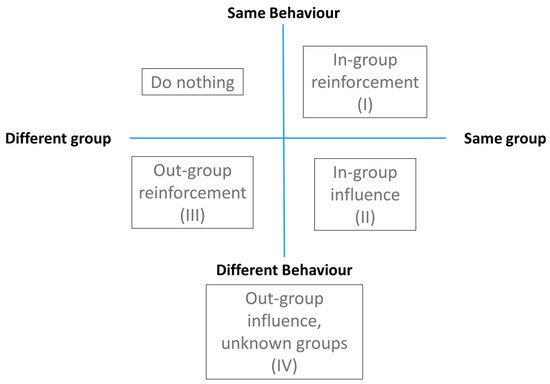

Figure 6 summarises the four types of social interactions by meat-eating behaviour and social groups. When two people with the same behaviour and in the same group meet, they engage in in-group reinforcement (type I) and they are more rooted in their current behaviour after the interaction. When two people in the same social group with different eating behaviour meet, they exert in-group influence on each other, and they are more likely to change their current behaviour (type II). When two people in different social groups with different social behaviour meet, they exert (negative) reinforcement effect on each other, and become less likely to convert to the other’s behaviour (type III). Finally, when two people with different eating behaviours meet and do not know each other’s social groups, they exert a positive social influence on each other (type IV), although the level of influence is less than if they belonged to the same social group. Additionally, when two people in different social groups and with the same eating behaviour meet, their social accounting does not change after the interaction. In summary, both in-group and out-group influence promote changes in behaviour, while both in-group and out-group reinforcement promote the status quo.

Figure 6 summarises the four types of social interactions by meat-eating behaviour and social groups. When two people with the same behaviour and in the same group meet, they engage in in-group reinforcement (type I) and they are more rooted in their current behaviour after the interaction. When two people in the same social group with different eating behaviour meet, they exert in-group influence on each other, and they are more likely to change their current behaviour (type II). When two people in different social groups with different social behaviour meet, they exert (negative) reinforcement effect on each other, and become less likely to convert to the other’s behaviour (type III). Finally, when two people with different eating behaviours meet and do not know each other’s social groups, they exert a positive social influence on each other (type IV), although the level of influence is less than if they belonged to the same social group. Additionally, when two people in different social groups and with the same eating behaviour meet, their social accounting does not change after the interaction. In summary, both in-group and out-group influence promote changes in behaviour, while both in-group and out-group reinforcement promote the status quo.

- Change tendency

- Social accounting

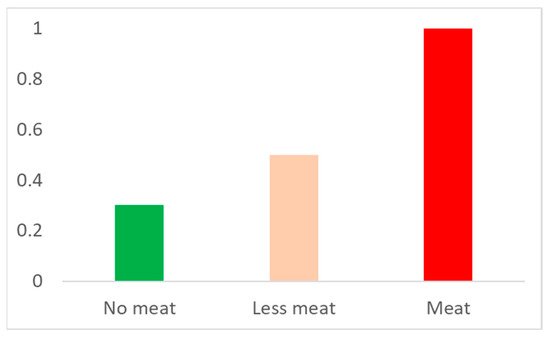

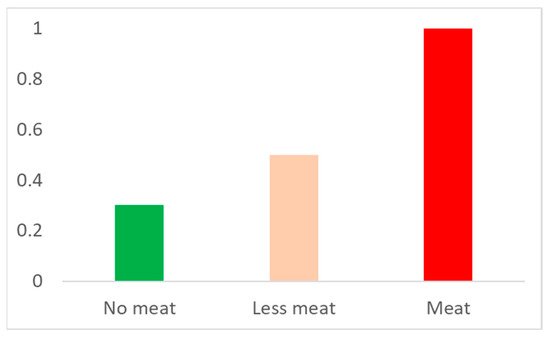

Figure 1.

An agent’s social accounting for different meat consumption behaviour.

2.2. Process: Four Types of Peer Influence

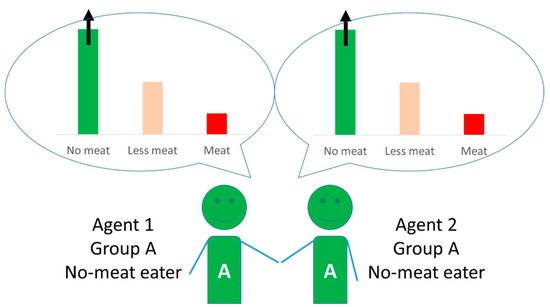

2.2.1. In-Group Reinforcement: Same Group, Same Behaviour

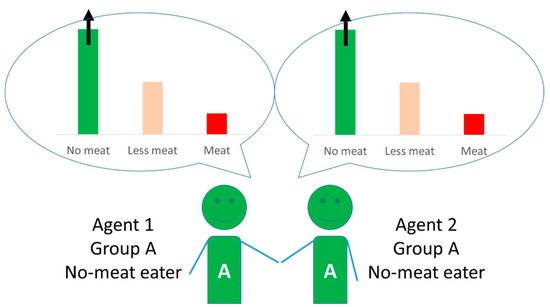

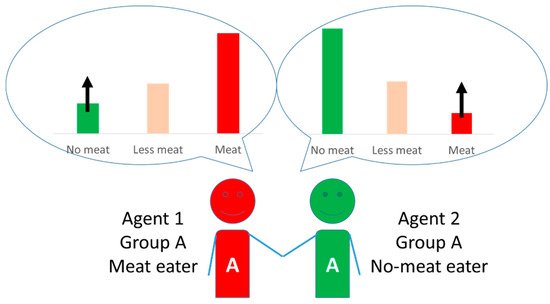

The first type of social interaction, in-group reinforcement, occurs when two agents in the same group with the same eating behaviour meet. As demonstrated in Figure 2, both agent 1 and 2 belong to the same social group (group A) and have the same dietary behaviour (no-meat eater). Because the two agents are identified as in the same group and they have the same behaviour, their social accounting for their current behaviour (no-meat eater) will both increase. Hence their current meat-eating behaviour will be reinforced after the interaction.

Figure 2. Social accounting for in-group reinforcement: Same group, same behaviour.

2.2.2. In-Group Influence: Same Group, Different Behaviour

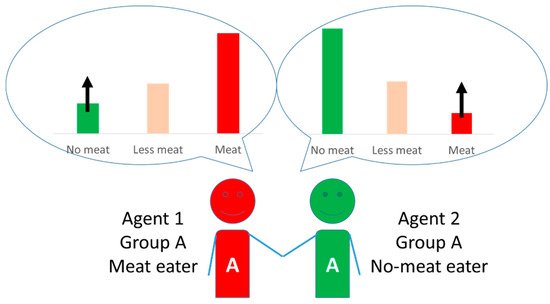

The second type of social interaction, in-group influence, occurs when two agents are in the same social identity group but have different eating behaviours. Because the agents identify each other as being in the same group, they will exert a positive influence on one another. As demonstrated in Figure 3, agent 1 is a meat eater and agent 2 is a no-meat eater, and both are in the social group A. Since both agents 1 and 2 are in the same social group, agent 1’s social accounting for no-meat eaters will increase after meeting agent 2; so will agent 2’s social accounting for meat-eaters after meeting agent 1. In-group influence will increase the social accounting score for different behaviour, making it slightly more appealing to the agent, although the change may not be enough to reach the behaviour-changing threshold.

Figure 3. Social accounting for in-group influence: Same identity, different behaviour.

2.2.3. Out-Group Reinforcement: Different Group, Different Behaviour

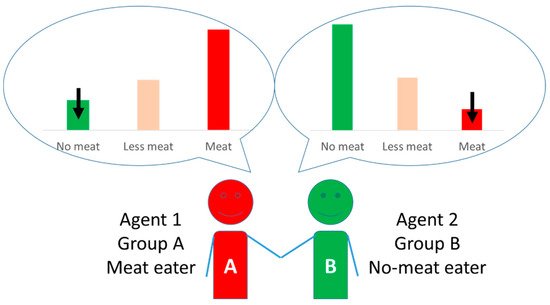

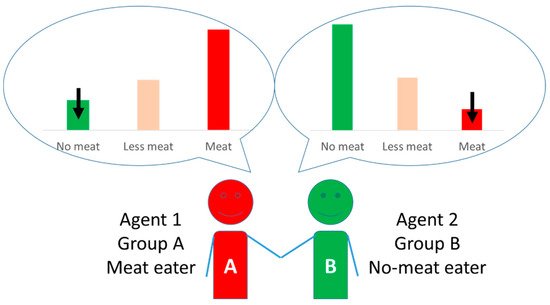

The third type of social interaction, out-group reinforcement, describes the process where two people in different social groups with different behaviours meet. As shown in Figure 4, agent 1 is a meat-eater who belongs to social group A, whereas agent 2 is a no-meat eater who belongs to social group B. Because they belong to different social groups, when agents 1 and 2 meet, both will lower the social accounting score for the behaviour of the other party after the interaction. Hence, agent 1’s score for no-meat eaters will decrease, and so will agent 2’s score for meat-eaters. This represents a process of ‘negative stereotyping’, i.e., that a behaviour performed by an out-group member makes it less appealing, which is documented in the literature as discussed previously [34][35]. Out-group reinforcement effect will reinforce the agent’s current behaviour by reducing the appeal of a different behaviour performed by an out-group member.

Figure 4. Social accounting for out-group reinforcement: Different identity, different behaviour.

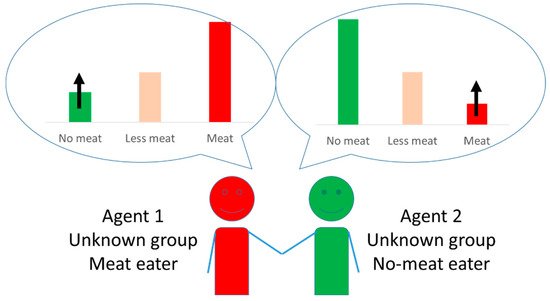

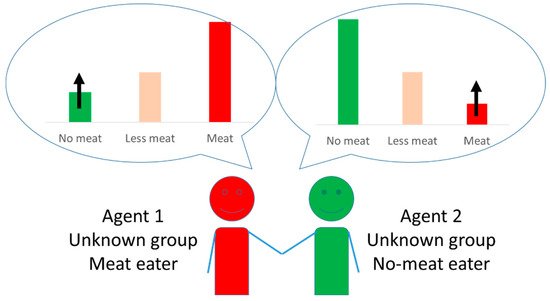

2.2.4. Out-Group Influence: Unknown Identity, Different Behaviour

Lastly, not all social interactions are driven by social groups or identities. In some social settings, the social group of the other person cannot be known or observed, in which case there will be out-group influence with unknown social groups. As shown in Figure 5, agents 1 and 2 do not know each other’s social groups. Agent 1 is a meat eater and agent 2 is a no-meat eater. After meeting agent 2, agent 1’s social accounting for no-meat eaters will increase, and vice versa. Under out-group influence with unknown social groups, a person’s social accounting for a certain behaviour increases after observing the behaviour of others, according to descriptive norms theory [44]. Researchers also assume that out-group influence only happens among agents living in the same region, when they are more likely to mingle and observe each other’s eating behaviours.

Figure 5. Social accounting for out-group influence: Unknown identity, different behaviour.

Figure 6. Four types of social interactions: in-group reinforcement (I), in-group influence (II), out-group reinforcement (III), and out-group influence with unknown identity (IV).

References

- The Vegan Society. Changing Diets during the COVID-19 Pandemic. 2021. Available online: https://www.vegansociety.com/sites/default/files/uploads/downloads/Changing%20Diets%20During%20the%20Covid-19%20Pandemic.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Clark, M.A.; Springmann, M.; Hill, J.; Tilman, D. Multiple health and environmental impacts of foods. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 23357–23362.

- Clark, H.; Wu, H. The Sustainable Development Goals: 17 Goals to Transform Our World. In Furthering the Work of the United Nations; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2016.

- UK Government. A Green Future: Our 25 Year Plan to Improve the Environment; Department for Environment, Fisheries and Rural Affairs: London, UK, 2018.

- Opio, C.; Gerber, P.; Mottet, A.; Falcucci, A.; Tempio, G.; MacLeod, M.; Vellinga, T.; Henderson, B.; Steinfeld, H. Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Ruminant Supply Chains–A Global Life Cycle Assessment; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2013.

- Chong, E.W.-T.; Simpson, J.A.; Robman, L.D.; Hodge, A.; Aung, K.Z.; English, D.; Giles, G.; Guymer, R. Red meat and chicken consumption and its association with age-related macular degeneration. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2009, 169, 867–876.

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Cancer: A Global Perspective. Continuous Update Project Expert Report. 2018. Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Summary-of-Third-Expert-Report-2018.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Chan, D.S.; Lau, R.; Aune, D.; Vieira, R.; Greenwood, D.C.; Kampman, E.; Norat, T. Red and processed meat and colorectal cancer incidence: Meta-analysis of prospective studies. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e20456.

- Lin, C.-L. Stroke and diets–A review. Tzu-Chi Med. J. 2021, 33, 238.

- Clune, S.; Crossin, E.; Verghese, K. Systematic review of greenhouse gas emissions for different fresh food categories. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 766–783.

- Aleksandrowicz, L.; Green, R.; Joy, E.J.M.; Smith, P.; Haines, A. The impacts of dietary change on greenhouse gas emissions, land use, water use, and health: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0165797.

- Bianchi, F.; Dorsel, C.; Garnett, E.; Aveyard, P.; Jebb, S.A. Interventions targeting conscious determinants of human behaviour to reduce the demand for meat: A systematic review with qualitative comparative analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. 2018, 15, 102.

- Bianchi, F.; Garnett, E.; Dorsel, C.; Aveyard, P.; Jebb, S.A. Restructuring physical micro-environments to reduce the demand for meat: A systematic review and qualitative comparative analysis. Lancet Planet. Health 2018, 2, e384–e397.

- Kim, Y.-H. Organic shoppers’ involvement in organic foods: Self and identity. Br. Food J. 2018, 121, 139–156.

- DellaPosta, D.; Shi, Y.; Macy, M. Why do liberals drink lattes? Am. J. Sociol. 2015, 120, 1473–1511.

- Plante, C.N.; Rosenfeld, D.L.; Plante, M.; Reysen, S. The role of social identity motivation in dietary attitudes and behaviors among vegetarians. Appetite 2019, 141, 104307.

- Gossard, M.H.; York, R. Social structural influences on meat consumption. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 2003, 10, 1–9.

- Hopwood, C.J.; Bleidorn, W.; Schwaba, T.; Chen, S. Health, environmental, and animal rights motives for vegetarian eating. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230609.

- Cruwys, T.; Bevelander, K.E.; Hermans, R.C.J. Social modeling of eating: A review of when and why social influence affects food intake and choice. Appetite 2015, 86, 3–18.

- Exline, J.J.; Zell, A.L.; Bratslavsky, E.; Hamilton, M.; Swenson, A. People-Pleasing Through Eating: Sociotropy Predicts Greater Eating in Response to Perceived Social Pressure. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2012, 31, 169–193.

- Hermans, R.C.J.; Engels, R.C.; Larsen, J.K.; Herman, C.P. Modeling of palatable food intake. The influence of quality of social interaction. Appetite 2009, 52, 801–804.

- Iacoboni, M. Imitation, Empathy, and Mirror Neurons. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2009, 60, 653–670.

- Van Baaren, R.B.; Holland, R.W.; Kawakami, K.; Van Knippenberg, A. Mimicry and Prosocial Behavior. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 15, 71–74.

- Einhorn, L. Normative Social Influence on Meat Consumption; MPIfG Discussion Paper; Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies: Cologne, Germany, 2020.

- McPherson, M. A Blau space primer: Prolegomenon to an ecology of affiliation. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2004, 13, 263–280.

- Weber, M. From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology; Routledge: London, UK, 2009.

- Holmgren, H. Plant-Based Diets on Social Media: How Content on Social Media Influence for Maintaining a Lifestyle. 2017. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1107865/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Faber, I.; Castellanos-Feijoó, N.A.; Van de Sompel, L.; Davydova, A.; Perez-Cueto, F.J. Attitudes and knowledge towards plant-based diets of young adults across four European countries. Exploratory survey. Appetite 2020, 145, 104498.

- Turner, J.C.; Tajfel, H. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. Psychol. Intergroup Relat. 1986, 5, 7–24.

- Hermans, R.C.J.; Larsen, J.K.; Herman, C.P.; Engels, R.C. Modeling of palatable food intake in female young adults. Effects of perceived body size. Appetite 2008, 51, 512–518.

- McFerran, B.; Dahl, D.W.; Fitzsimons, G.J.; Morales, A.C. I’ll Have What She’s Having: Effects of Social Influence and Body Type on the Food Choices of Others. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 36, 915–929.

- Cruwys, T.; Platow, M.J.; Angullia, S.A.; Chang, J.M.; Diler, S.E.; Kirchner, J.L.; Lentfer, C.E.; Lim, Y.J.; Quarisa, A.; Tor, V.W.; et al. Modeling of food intake is moderated by salient psychological group membership. Appetite 2012, 58, 754–757.

- Berger, J.; Heath, C. Who drives divergence? Identity signaling, outgroup dissimilarity, and the abandonment of cultural tastes. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2008, 95, 593–607.

- Berger, J.; Rand, L. Shifting signals to help health: Using identity signaling to reduce risky health behaviors. J. Consum. Res. 2008, 35, 509–518.

- Oyserman, D.; Fryberg, S.A.; Yoder, N. Identity-based motivation and health. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 93, 1011–1027.

- Upal, M.A.; Gibbon, S. Agent-based system for simulating the dynamics of social identity beliefs. In SpringSim; ANSS: Canonsburg, PA, USA, 2015.

- Smaldino, P.E.; Calanchini, J.; Pickett, C.L. Theory development with agent-based models. Organ. Psychol. Rev. 2015, 5, 300–317.

- Nan, N.; Johnston, E.W.; Olson, J.S.; Bos, N. Beyond being in the lab: Using multi-agent modeling to isolate competing hypotheses. In CHI’05 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2005.

- Rousseau, D.; van der Veen, A.M. The Emergence of a Shared Identity: An Agent-Based Computer Simulation of Idea Diffusion. J. Confl. Resolut. 2005, 49, 686–712.

- Kustov, A. How ethnic structure affects civil conflict: A model of endogenous grievance. Confl. Manag. Peace Sci. 2017, 34, 660–679.

- Moulin, B.; Larochelle, B. Crowdmags: Multi-agent geo-simulation of the interactions of a crowd and control forces. In Modelling, Simulation and Identification; Department of Computer Sciences and Software Engineering, Laval University: Quebec City, QC, Canada, 2010; pp. 213–237.

- Chabay, I.; Koch, L.; Martinez, G.; Scholz, G. Influence of narratives of vision and identity on collective behavior change. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5680.

- Valkering, P.; Tabara, D.; Wallman, P.; Offermans, A. Modelling cultural and behavioural change in water management: An integrated, agent based, gaming approach. Integr. Assess. J. 2009, 9. Available online: https://journals.lib.sfu.ca/index.php/iaj/article/view/2746 (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Cialdini, R.B.; Reno, R.R.; Kallgren, C.A. A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Q. 1990, 58, 1015.

More