Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Karolina Jałbrzykowska and Version 3 by Catherine Yang.

Enoxacin is a second-generation quinolone with promising anticancer activity. In contrast to other members of the quinolone group, it exhibits an extraordinary cytotoxic mechanism of action. Enoxacin enhances RNA interference and promotes microRNA processing, as well as the production of free radicals. Interestingly, apart from its proapoptotic, cell cycle arresting and cytostatic effects, enoxacin manifests a limitation of cancer invasiveness. The underlying mechanisms are the competitive inhibition of vacuolar H+-ATPase subunits and c-Jun N-terminal kinase signaling pathway suppression. The mentioned mechanisms seem to contribute to a safer, more selective and more effective anticancer therapy.

- enoxacin

- miRNA

- RISC

- SMER

1. The miRNA Biogenesis

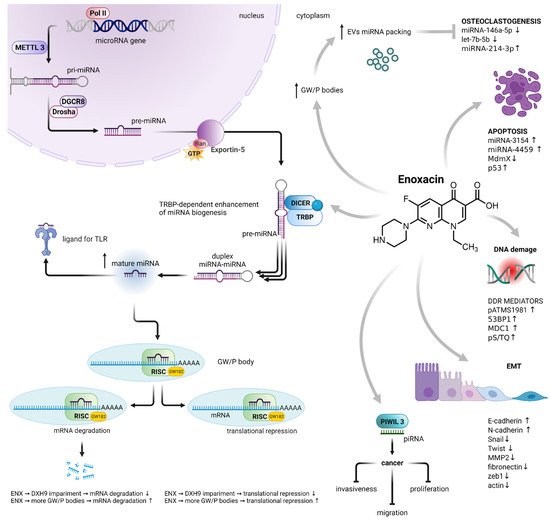

The miRNA biogenesis begins with transcribing a gene into a large primary transcript (pri-miRNA). The transcription is typically mediated by RNA polymerase II.[1] The pri-miRNAs are then cleaved by the microprocessor complex, composed of the RNA-binding protein DGCR8 and type III RNase Drosha, into a stem-loop structure called the precursor miRNA (pre-miRNA).[2] Following transportation by the Ran/GTP/Exportin5 complex from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, the pre-miRNAs are processed by another RNase III enzyme DICER into an miRNA/miRNA duplex. After the duplex is unwound, the mature miRNA is incorporated into a protein complex termed the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). The miRNA-loaded RISC mediates gene silencing via mRNA cleavage and degradation or translational repression, depending on the complementarity between the miRNA and the targeted mRNA transcript.[3] An important role in translational repression and mRNA degradation is played by GW182 protein. Its N-terminal domain is rich in glycine (G) and tryptophan (W) amino acids, while the C-terminus contains a silencing domain. GW182 directs proteins involved in deadenylation, decapping and exonucleolytic degradation of the target mRNA.[4] GW182 binds directly to AGO2, another member of the RISC[5] GW182, AGO2 and rest of the RISC can be found within GW processing bodies (GW/P-bodies).[6],[7] Interestingly, miRNAs may function as ligands directly binding the Toll-like receptor (TLR), triggering downstream signaling pathways[8] (Figure 12).

Figure 12. Enoxacin-induced dysregulation of miRNA biogenesis and its consequences. Enoxacin enhanced the activity of the RISC loading protein TRBP, resulting in an increase in the number of mature miRNAs. It also impairs the activity of DHX9 helicase, a member of the RISC, leading to the impairment of mRNA translational repression and degradation. On the other hand, it increases the number of GW/P bodies, the sites of RNA-mediated silencing, as well as the localization of miRNA packaging into EVs. The enoxacin-dysregulated biogenesis of miRNA is involved in osteoclastogenesis, apoptosis, DNA damage response, epithelial–mesenchymal transition, cancer cell proliferation, migration and invasiveness. Abbreviations: polymerase II (Pol II); methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3); microprocessor complex subunit DGCR8 (DGCR8); type III RNase Drosha (Drosha); GTP-binding nuclear protein Ran (Ran); endoribonuclease DICER (DICER); TAR RNA-binding protein 2 (TRBP); Toll-like receptor (TLR); RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC); GW processing body (GW/P-body); Piwi-interacting RNA (piRNA); epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT); matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP2); DNA damage response (DDR); extracellular vesicles (EVs). MiRNA biogenesis adapted from[2] Created with BioRender.com.

It has been clear for almost twenty years that miRNA expression is dysregulated in human malignancies. The underlying mechanisms include chromosomal abnormalities,[9],[10],[11],[12],[13],[14] transcriptional control changes,[15],[16],[17] epigenic changes and defects in the miRNA biogenesis machinery.[18],[19],[20]

2. The Effect on Cancer Cells

2.1. TRBP-Dependent Cytotoxicity

Small molecules can influence miRNA biogenesis. Enoxacin was reported as the first and unique small-molecule enhancer of microRNA (SMER) maturation.[21]

Jin et al. found that the increase in miRNAs was associated with high levels of their own precursors, thereby suggesting that enoxacin could promote the DICER processing activity without influencing the miRNA precursor expression.[21] The same authors established that the enoxacin activity was dependent on the TAR RNA-binding protein 2 (TRBP) and likely involved in the improvement of the TRBP-pre-miRNA affinity.[21]

The role of the TRBP in enoxacin-mediated cytotoxicity was confirmed in the three colorectal cancer cell lines (Co115, RKO and HCT-116) and their mutants with impaired TRBP expression. TRBP-impaired cells were more resistant to enoxacin, resulting in a 2-fold increase in the effective concentration (EC50). Mutant cells also did not undergo cell cycle arrest. Additionally, enoxacin induced a two-fold expression increase in 24 miRNAs in RKO and HCT-116 cells and from 1.5-fold up two five-fold increases in the expression of those miRNAs in RKO and HCT-116 xenograft mouse model. Enoxacin treatment also significantly decreased the number of lung and liver metastases in the HCT-116 xenograft.[22] Interestingly, ENX increased the TRBP-dependent miRNA expression in Ewing’s sarcoma family tumor (ESFT) cell lines such as A673, TC252 and STA-ET-8.2, but not the expression of TRBP itself. It caused a 50% reduction in sphere formation; increased the expression of a panel of TRBP/DICER-dependent miRNAs; and decreased the expression of Oct-4, Nanog and Sox-2 proteins in primary ESFT spheres. This effect was similar to the introduction of exogenous TRBP. Thus, enoxacin can cause a decrease in the self-renewal of ESFT cancer stem-like cells (CSC).[23] However, this fluoroquinolone also significantly decreased TRBP and DICER protein expression levels in the prostate cancer cell lines DU145, LNCaP, VCaP, PC-3, 22Rv1 and Co115 via the induction of apoptosis. At the same time, it dysregulated the expression of a wide range of miRNAs involved in the development and progression of prostate cancer, e.g., miRNA-29b, which regulates the expression of the proteins E-cadherin, N-cadherin, Snail, Twist and matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP2) involved in the metastatic process.[24] The effect of the increased expression of tumor-suppressing miRNA was also notable in thyroid cancer cells lines (Cal62, TPC1, SW1736). This resulted in lower cell proliferation and cell invasiveness in vitro. The decreased expression of epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) markers such as fibronectin, n-cadherin, zeb1, twist and actin was also observed. The upregulation of tumor suppressor miRNA, as well as the suppression of EMT markers, was also shown in the orthotopic mouse model of human thyroid cancer. The results were consistent with those using miRNA-restoring DICER1 silencing (miRNA-30a and miRNA-100). This suggests that enoxacin promotes the restoration of DICER1 activity in DICER1-impaired cells, e.g., human thyroid cancer cells.[25]

The role of enoxacin as an enhancer of DNA damage response (DDR) signaling was confirmed in cervical cancer HeLa cells. This antibiotic augmented the DDR mediator factors pATMS1981, 53BP1, MDC1 and pS/TQ without affecting their expression, whereas the activity of γH2AX levels was not affected. Based on the knowledge of the activation of TRBP by enoxacin, it is not surprising that TRBP silencing diminished ENX’s stimulation of DDR. The knockdown of PACT or GW182 proteins (TNRC6A, B and C), which are effectors for miRNA-guided gene silencing, did not affect ENX-mediated DDR stimulation. These results seem to strengthen and confirm enoxacin’s specificity towards TRBP.[26]

2.2. PIWIL-3-Dependent Cytotoxicity

Regarding the molecular target recognized by enoxacin, an additional protein has been proposed that merits mentioning. In 2017, Abell et al. determined that the Piwi-like protein 3 (PIWIL3) is a potential enoxacin target.[27] PIWIL3 belongs to the PIWI argonaut proteins involved in the maturation of the PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs), small non-coding RNAs that differ from miRNAs.[28] Although mostly present in normal testis tissue, PIWIL3 has been reported to be aberrantly expressed in a variety of cancers, playing important roles in tumorigenesis.[29],[30] An increase in miRNA-21 and miRNA-145 expression was observed in breast cancer MCF7 cells. Similar results were obtained in cells with small interfering RNA-mediated knockout of the PIWIL3. The staining with alkenox, a synthetic enoxacin analog, showed that PIWIL3 might be a mechanistic target of enoxacin.[27] Since PIWIL3 is more abundant in cancer cells, it might in part explain the specificity of ENX towards cancer cells.[27],[30]

2.3. Other Consequences of Enoxacin-Mediated miRNA Dysregulation

Additionally, ENX affected RNA helicase DHX9, a member of the RISC. The expression of DHX9 was much higher in the small-cell lung cancer cell line H446 than in the non-small-cell lung carcinoma cell lines A549 and PC9. Enoxacin inhibited the proliferation of A549 in a dose-dependent manner. Similarly, it decreased the expression of DHX9 in A549 cells. However, silencing DHX9 impaired the cytotoxic effect of the drug.[31]

A strong inhibitory effect of enoxacin on the proliferation of human melanoma A375, Mel-Juso and Mel-Ho cell lines was observed. It dysregulated a set of 55 miRNAs in A375 cells (26 upregulated, 29 downregulated). Two upregulated miRNAs, miRNA-3154 and miRNA-4459, control the p53-Mdm2-MdmX network.[32] Interestingly, in many melanomas the overexpression of MdmX, a p53 negative regulator, was observed.[33] Enoxacin increased p53’s activity without affecting its expression. At the same time, the expression of MdmX decreased in a dose-dependent manner. It alternates MdmX splicing by promoting exon 6 skipping. This process was observed in different cancer cell lines (A375, A2780 and MCF7).[34]

A different ENX antiproliferative mechanism without affecting apoptosis has been noted in 4T1 murine breast cancer cells. An increased level of GW/processing bodies, which are considered the surrogate markers for both the microRNA-mediated repression of translation and the extracellular vesicle (EV) packaging sites, was observed. MiRNA expression levels in the 4T1 cells’ cytosol and their EV were compared. Enoxacin significantly increased only miRNA-214-3p and slightly increased miRNA-146a-5p, miRNA-290, miRNA-689 and let-7b-5p cytosolic levels. In contrast, significant decreases in let-7b-5p, miRNA-146a-5p and miRNA-689 expression and an enormous 22-fold increase in miRNA-214-3p were observed. All mentioned miRNAs are involved in the regulation of bone remodeling and osteoclastogenesis. Additionally, EVs from enoxacin-treated 4T1 cells enhanced the proliferation of murine macrophage cells.[35] The effective concentration range affecting miRNA biogenesis (see Table 1) was from 50 to 124 µM; however, an achievable serum concentration for a standard clinical dose 400 mg two times a day was ca. 10 µM. Reduction of effective concentration could be obtained by structural modification of enoxacin. Significant decrease of IC50 was observed after structure modification of other fluoroquinolones, i.e., by fatty acid conjugation.[36],[37] Moreover, it should be considered that tumor vessels are often more permeable compared to normal vessels, which could increase the ENX delivery and its intratumor concentration.[38]

Although it has been clear that enoxacin did not affect all existing miRNAs (e.g., 36 out of 22,000 tested in normal HEK293 cells[21] and 122 out 731 tested in cancer RKO cells[22]). It is worth mentioning that this may be partially explained by the existence of the alternative miRNA biogenesis pathways, which do not contain molecular targets of enoxacin.[39],[40],[41] Interestingly, the dysregulated miRNAs play an important role in cancer-related processes, e.g., miR-17* decreased the activity of mitochondrial antioxidative enzymes in PC3 cells;[42] miR-34a downregulated an oxidative-stress-induced silent information regulator 1 (SIRT1), a negative regulator of p53 protein, in HCT116 cells;[43] miR-30a-5p suppressed the epithelial–mesenchymal transition in SW480 cells by targeting integrin β3 (ITGB3);[44] and miR-212 was observed to inhibit the viability and invasion of HCT116 and SW620 cells via inhibition of the phosphoinositide-3-kinase regulatory subunit 3 (PIK3R3) expression.[45] An investigation of the role of the dysregulated miRNAs would definitely help to better understand the mechanism of enoxacin-mediated anticancer activity. However, the detailed molecular targets of particular tumor-suppressing or oncogenic miRNAs are beyond the scope of this rentryview and have been described elsewhere.[46],[47], [48],[49],[50]

3. The Effects on Non-Cancer Cells

It is worth mentioning that enoxacin affects not only cancer cells; it also increased the levels of miRNA related to the disease in the dominant negative TGF-β receptor (dnTGFβRII) CD8 cells from an autoimmune cholangitis mouse model. Despite the fact that enoxacin did not change the amount of CD8 T cells, it significantly decreased their proliferative response. Enoxacin also significantly decreased the level of interferon γ in mouse serum.[51] There is some research concerning enoxacin’s impact on the neuronal system. Rats treated with 10 or 25 mg/kg enoxacin for 1 week were found to have elevated levels of miRNA related to the neuronal cell biology in their frontal cortex (Table 2). Those miRNAs include let-7, miRNA-124, miRNA-125 and miRNA-132. They are involved in the processes of neurogenesis (let-7, miR-124) and neuronal differentiation in human (miRNA-125) and mouse (miRNA-124) brains, the regulation of the dendritic spine length in mammalian neurons (miR-125NA), as well as neurite outgrowth (miRNA-132). The enoxacin-treated rats were also less likely to exhibit learned helplessness when they faced an inescapable shock.[52]

Enoxacin is also capable of affecting artificial miRNAs (amiRNAs), especially by enhancing the amiRNA-mediated reversible inhibition of the CRISPR-Cas9 system in both in vitro and in vivo studies. Interestingly, amiRNA alone did not show an inhibitory effect towards the CRISPR-Cas9 system, indicating the crucial role of enoxacin. In contrast, some of the naturally occurring miRNAs were able to inhibit CRISPR-Cas9 activity by binding to single-guide RNA (sgRNA), a part of the sgRNA/Cas9 complex, in the absence of enoxacin. Surprisingly, the presence of enoxacin in concentrations up to 50 µM did not affect the natural miRNAs’ influence on the CRISPR system. The proposed explanation of these differences in the impacts of enoxacin on the inhibition of natural and artificial miRNAs is based on the low binding capacity of amiRNAs towards RISC and the high binding capacity towards the RISC of natural miRNAs. Another factor could be the difference in the amounts of amiRNAs vs. natural miRNAs. The amiRNAs are believed to outnumber natural miRNAs. Taking the above into account, the amiRNA/enoxacin system turned out to be specific and reversible, making it a convenient tool for CRISPR-Cas9 regulation.[53]

In 2008, Shan et al. investigated the ability of microRNA processing to enhance some fluoroquinolones, including enoxacin and its three derivatives. They identified the structural elements of enoxacin responsible for its activity, such as a carboxyl group at the 3rd carbon atom, fluorine at the 7th carbon atom, as well as nitrogen at the 8th position of naphyridine.[21]

Table 1.

The miRNA-regulating activity levels in in vitro studies depending on the different enoxacin concentrations.

| miRNA | Conc. [µM] | Effect | Expression Change | Cell Line | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [↑/↓] | Change-Fold |

| miRNA | Dose | Effect | Expression Change: | Tissue | Ref. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [↑/↓] | Change-Fold | ||||||||||

| Cancer cells | |||||||||||

| let-7b-5p, miR-146a-5p, miR-689 | 50 | ↓ | |||||||||

| 1.5–2 | |||||||||||

| 124 | |||||||||||

| ↑ | |||||||||||

| 3–3.5 | |||||||||||

| HCT-116, RKO | |||||||||||

| [ | |||||||||||

| 22 | |||||||||||

| ] | |||||||||||

| let-7f, miR-143, miR-181a, | |||||||||||

| miR-124 | 10 mg/kg 25 mg/kg |

↑ | ca. 4. ca. 6 |

rat frontal cortex | [52] | ||||||

| 0.5–1 | 4T1 (miRNA from EV), | [ | 35 | ] | |||||||

| 124 | |||||||||||

| ↑ | |||||||||||

| 3–3.5 | |||||||||||

| A673, STA-ET-8.2, primary ESFT spheres | |||||||||||

| let-7a, miR-125a-5p | |||||||||||

| [ | |||||||||||

| 23 | |||||||||||

| ] | |||||||||||

| 10 mg/kg | 25 mg/kg |

↑ | ca. 11. ca. 20 |

miR-100 | 124 | ↓ | 0.5–1 | primary ESFT spheres | [23] | ||

| miR-132 | 10 mg/kg 25 mg/kg |

↑ | ca. 19 (for both doses) |

miR-141, miR-191 | 124 | ↓ | 1.5–2 | DU145, LNcap, | |||

| miR-30a-5p, miR-146b-5 | 15 mg/kg | [ | ↑ | 24 | ] | ||||||

| human orthotopic thyroid tumor from Cal62-luc mouse | [ | 25 | ] | miR-21-5p, miR-30a-3p, miR-30a-5p, miR-100-5p, miR-204-5p, miR-221-3p | 124 | ↑ | <1.5 | Cal62, STA-ET-8.2, TPC1 | [ | ||

| mIR-100-5p, miR-30-3p, miR-204-5 | 15 mg/kg | 25 | ] | ||||||||

| ↑ | 2–2.5 | human orthotopic thyroid tumor from Cal62-luc mouse | [ | 25 | ] | Let-7f, miR-26a, | 124 | ↑ | <1.5 | A673, SW1736 | [23] |

| miR-16, miR-18a*, miR-21, miR-26a, miR-29b, miR-29c, miR-31, miR-101, miR-193a | 10 mg/kg | ↑ | 1.5–2 | tumor from HCT-116 mouse xenograft | [22] | miR-21 | 100 | ↑ | 1.5–2 | MCF7 | [27] |

| miR-16, miR-29c, miR-31, miR-101, miR-181a | 10 mg/kg | ↑ | 1.5–2 | tumor from RKO mouse xenograft | [22] | miR-16, miR-18a*, miR-21, miR-26a, miR-29b, miR-29c, miR-31, miR-193a, | 124 | ↑ | |||

| miR-128, miR-212 | 10 mg/kg | 1.5–2 | ↑ | HCT-116 | 2–2.5[22] | ||||||

| tumor from HCT-116 mouse xenograft | [ | 22 | ] | let-7f, miR-26a, miR-99a, miR-100, miR-143, miR-145, | 124 | ↑ | 1.5–2 | ||||

| miR-18a*, miR-21, miR-26a, miR-29b, miR-30a, miR-128 | 10 mg/kg | ↑ | A673, STA-ET-8.2, TC252, primary ESFT spheres | [ | 23] | ||||||

| 2–2.5 | tumor from RKO mouse xenograft | [ | 22 | ] | miR-21-5p, miR-30a-3p, miR-100-5p, miR-146b-5p, miR-221-3p, | 124 | ↑ | 1.5–2 | Cal62, SW1736, TPC1 | [ | |

| let-7b, miR-7, miR-143, miR-181b, miR-125b | 10 mg/kg | 25 | ↑ | ] | |||||||

| 2.5–3 | tumor from HCT-116 mouse xenograft | [ | 22 | ] | miR-17 *, miR29b, miR-132, miR-146a, miR-191 miR-449a, | 124 | ↑ | 1.5–2 | DU145 LNcap, | [24] | |

| let-7a, miR-7, miR-122, miR-125a, miR-125b, miR-126, miR-181b, miR-193a, miR-193b, miR-205, miR-212 | 10 mg/kg | ↑ | 2.5–3 | tumor from RKO mouse xenograft | [22] | miR-214-3p | 50 | ↑ | 2–2.5 | 4T1 (cytosolic miRNA), | [35] |

| let-7a, miR-30a, miR-122, miR-126 | 10 mg/kg | ↑ | 3–3.5 | tumor from HCT-116 mouse xenograft | [22] | miR-145 | 100 | ↑ | 2–2.5 | MCF7 | [27] |

| miR-143 | 10 mg/kg | ↑ | 3–3.5 | tumor from RKO mouse xenograft | [22] | miR-7, miR-16, miR-18a*, miR-29c, miR-101, miR-128, miR-181a, miR-212 | 124 | ↑ | 2–2.5 | HCT-116, RKO | [ |

| miR-125a, miR-181a, miR-193b | 10 mg/kg | 22 | ↑ | ] | |||||||

| 3.5–4 | tumor from HCT-116 mouse xenograft | [ | 22 | ] | miR-100-5p, miR-146b-5p | 124 | ↑ | 2–2.5 | SW1736, TPC1 | [25] | |

| let-7b | 10 mg/kg | ↑ | 4.5–5 | tumor from RKO mouse xenograft | [22] | miR-34a, miR-449a | 124 | ||||

| miR-205 | 10 mg/kg | ↑ | 2–2.5 | DU145, LNcap | ↑ | 4.5–5[24 | tumor from HCT-116 mouse xenograft] | ||||

| [ | 22 | ] | let-7f, miR-99a, miR-100, miR-145 | 124 | ↑ | 2–2.5 | A673, STA-ET-8.2, TC252, primary ESFT spheres | [23] | |||

| miR-7, miR-26a, miR-29b, miR-30a, miR-101, miR-122, miR-125a, miR-125b, miR-126, miR-128, miR-143, miR-181b, miR-205 | 124 | ↑ | 2.5–3 | HCT-116, RKO | [22] | ||||||

| miR-100, miR-145 | 124 | ↑ | 2.5–3 | A673, TC252 | [23] | ||||||

| miR-29b | 124 | ↑ | 2.5–3 | LNcap | [24] | ||||||

| let-7a, let-7b, miR-30a, miR-31, miR-126, miR-181b, miR-193a, miR-193b, | miR-181a, miR-193b | 124 | ↑ | 3.5–4 | HCT-116 | [22] | |||||

| let-7b, miR-143, miR-205 | 124 | ↑ | 4–4.5 | HCT-116, RKO | [22] | ||||||

| miR-143 | 124 | ↑ | 4–4.5 | TC252 | [23] | ||||||

| miR-125a | 124 | ↑ | ca. 5 | HCT-116 | [22] | ||||||

| miR-214-3p | 50 | ↑ | ca. 22 | 4T1 (miRNA from EV) | [35] | ||||||

| Non-cancer cells | |||||||||||

| miR-128-1 | 60 | ↓ | 0.5–1 | dnTGFβRII T cells | [51] | ||||||

| let-7i, miR-128 | 50 | ↓ | 1.5–2 | HEK293 | [21] | ||||||

| let-7b, miR-23a, miR-30e, miR-96, miR-99a, miR-125a, miR-146, miR-190, miR-199a*, | 50 | ↑ | 1.5–2 | HEK293 | [21] | miR-124a, miR-139, miR-152, miR-199b | 50 | ↑ | 2–2.5 | HEK293 | [21] |

| miR-29b-1, miR-145a-5p, miR-326-3p | 60 | ↑ | 2–2.5 | dnTGFβRII T cells | [51] | ||||||

| miR-181a | 60 | ↑ | 2.5–3 | dnTGFβRII T cells | [51] | ||||||

| miR-346-5 | 60 | ↑ | 3–3.5 | dnTGFβRII T cells | [51] | ||||||

Dominant negative TGF-β receptor (dnTGFβRII). Please note that “*” is not a footnote indicator, but an essential part of the name of the specific miRNA. More information regarding the miRNAs’ nomenclature can be found in miRBase.[54]

Table 2.

The miRNA regulating activity levels in in vivo studies depending on the different enoxacin concentrations.

References

- Yoontae Lee; Minju Kim; Jinju Han; Kyu-Hyun Yeom; Sanghyuk Lee; Sung Hee Baek; V Narry Kim; MicroRNA genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase II. The EMBO Journal 2004, 23, 4051-4060, 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600385.

- Yong Peng; Carlo M Croce; The role of MicroRNAs in human cancer. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2016, 1, 15004, 10.1038/sigtrans.2015.4.

- Leigh-Ann Macfarlane; Paul R. Murphy; MicroRNA: Biogenesis, Function and Role in Cancer. Current Genomics 2010, 11, 537-561, 10.2174/138920210793175895.

- Hiro-Oki Iwakawa; Yukihide Tomari; Life of RISC: Formation, action, and degradation of RNA-induced silencing complex. Molecular Cell 2021, 82, 30-43, 10.1016/j.molcel.2021.11.026.

- Rui Zhang; Ying Jing; Haiyang Zhang; Yahan Niu; Chang Liu; Jin Wang; Ke Zen; Chen-Yu Zhang; Donghai Li; Comprehensive Evolutionary Analysis of the Major RNA-Induced Silencing Complex Members.. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 14189, 10.1038/s41598-018-32635-4.

- Andrew Jakymiw; Kaleb M. Pauley; Songqing Li; Keigo Ikeda; Shangli Lian; Theophany Eystathioy; Minoru Satoh; Marvin J. Fritzler; Edward Chan; The role of GW/P-bodies in RNA processing and silencing. Journal of Cell Science 2007, 120, 1317-1323, 10.1242/jcs.03429.

- Jidong Liu; Fabiola V. Rivas; James Wohlschlegel; John R. Yates; Roy Parker; Gregory J. Hannon; A role for the P-body component GW182 in microRNA function. Nature Cell Biology 2005, 7, 1261-1266, 10.1038/ncb1333.

- Muller Fabbri; Alessio Paone; Federica Calore; Roberta Galli; Eugenio Gaudio; Ramasamy Santhanam; Francesca Lovat; Paolo Fadda; Charlene Mao; Gerard J. Nuovo; et al.Nicola ZanesiMelissa CrawfordGulcin H. OzerDorothee WernickeHansjuerg AlderMichael A. CaligiuriPatrick Nana-SinkamDanilo PerrottiCarlo M. Croce MicroRNAs bind to Toll-like receptors to induce prometastatic inflammatory response. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2012, 109, E2110-E2116, 10.1073/pnas.1209414109.

- George Adrian Calin; Calin Dan Dumitru; Masayoshi Shimizu; Roberta Bichi; Simona Zupo; Evan Noch; Hansjuerg Aldler; Sashi Rattan; Michael Keating; Kanti Rai; et al.Laura RassentiThomas KippsMassimo NegriniFlorencia BullrichCarlo M. Croce Frequent deletions and down-regulation of micro- RNA genes miR15 and miR16 at 13q14 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2002, 99, 15524-15529, 10.1073/pnas.242606799.

- G A Calin; C M Croce; MicroRNAs and chromosomal abnormalities in cancer cells. Oncogene 2006, 25, 6202-6210, 10.1038/sj.onc.1209910.

- Yoji Hayashita; Hirotaka Osada; Yoshio Tatematsu; Hideki Yamada; Kiyoshi Yanagisawa; Shuta Tomida; Yasushi Yatabe; Katsunobu Kawahara; Yoshitaka Sekido; Takashi Takahashi; et al. A Polycistronic MicroRNA Cluster, miR-17-92, Is Overexpressed in Human Lung Cancers and Enhances Cell Proliferation. Cancer Research 2005, 65, 9628-9632, 10.1158/0008-5472.can-05-2352.

- Konstantinos J. Mavrakis; Andrew L. Wolfe; Elisa Oricchio; Teresa Palomero; Kim De Keersmaecker; Katherine McJunkin; Johannes Zuber; Taneisha James; Aly A. Khan; Christina S. Leslie; et al.Joel S. ParkerPatrick J. PaddisonWayne TamAdolfo FerrandoHans-Guido Wendel Genome-wide RNA-mediated interference screen identifies miR-19 targets in Notch-induced T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature Cell Biology 2010, 12, 372-379, 10.1038/ncb2037.

- Lin Zhang; Jia Huang; Nuo Yang; Joel Greshock; Molly S. Megraw; Antonis Giannakakis; Shun Liang; Tara L. Naylor; Andrea Barchetti; Michelle R. Ward; et al.George YaoAngelica MedinaAnn O’Brien-JenkinsDionyssios KatsarosArtemis HatzigeorgiouPhyllis A. GimottyBarbara L. WeberGeorge Coukos microRNAs exhibit high frequency genomic alterations in human cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2006, 103, 9136-9141, 10.1073/pnas.0508889103.

- George Adrian Calin; Cinzia Sevignani; Calin Dan Dumitru; Terry Hyslop; Evan Noch; Sai Yendamuri; Masayoshi Shimizu; Sashi Rattan; Florencia Bullrich; Massimo Negrini; et al.Carlo M. Croce Human microRNA genes are frequently located at fragile sites and genomic regions involved in cancers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2004, 101, 2999-3004, 10.1073/pnas.0307323101.

- Kathryn A. O'Donnell; Erik A. Wentzel; Karen I. Zeller; Chi Dang; Joshua T. Mendell; c-Myc-regulated microRNAs modulate E2F1 expression. Nature 2005, 435, 839-843, 10.1038/nature03677.

- Tsung-Cheng Chang; Duonan Yu; Yun-Sil Lee; Erik A Wentzel; Dan E Arking; Kristin M West; Chi V Dang; Andrei Thomas-Tikhonenko; Joshua T Mendell; Widespread microRNA repression by Myc contributes to tumorigenesis. Nature Genetics 2007, 40, 43-50, 10.1038/ng.2007.30.

- Paloma Del C. Monroig; George A. Calin; MicroRNA and Epigenetics: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Opportunities. Current Pathobiology Reports 2013, 1, 43-52, 10.1007/s40139-013-0008-9.

- J. Michael Thomson; Martin Newman; Joel S. Parker; Elizabeth M. Morin-Kensicki; Tricia Wright; Scott M. Hammond; Extensive post-transcriptional regulation of microRNAs and its implications for cancer. Genes & Development 2006, 20, 2202-2207, 10.1101/gad.1444406.

- Yoko Karube; Hisaaki Tanaka; Hirotaka Osada; Shuta Tomida; Yoshio Tatematsu; Kiyoshi Yanagisawa; Yasushi Yatabe; Junichi Takamizawa; Shinichiro Miyoshi; Tetsuya Mitsudomi; et al.Takashi Takahashi Reduced expression of Dicer associated with poor prognosis in lung cancer patients. Cancer Science 2005, 96, 111-115, 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2005.00015.x.

- Jeffrey S. Dome; Max J. Coppes; Recent advances in Wilms tumor genetics. Current Opinion in Pediatrics 2002, 14, 5-11, 10.1097/00008480-200202000-00002.

- Ge Shan; Yujing Li; Junliang Zhang; Wendi Li; Keith E Szulwach; Ranhui Duan; Mohammad A Faghihi; Ahmad M Khalil; LiangHua Lu; Zain Paroo; et al.Anthony W S ChanZhangjie ShiQinghua LiuClaes WahlestedtChuan HePeng Jin A small molecule enhances RNA interference and promotes microRNA processing. Nature Biotechnology 2008, 26, 933-940, 10.1038/nbt.1481.

- Sonia Melo; Alberto Villanueva; Catia Moutinho; Veronica Davalos; Riccardo Spizzo; Cristina Ivan; Simona Rossi; Fernando Setien; Oriol Casanovas; Laia Simo-Riudalbas; et al.Javier CarmonaJordi CarrereAugust VidalAlvaro AytesSara PuertasSantiago RoperoRaghu KalluriCarlo M. CroceGeorge A. CalinManel Esteller Small molecule enoxacin is a cancer-specific growth inhibitor that acts by enhancing TAR RNA-binding protein 2-mediated microRNA processing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2011, 108, 4394-4399, 10.1073/pnas.1014720108.

- Claudio De Vito; Nicolo Riggi; Sandrine Cornaz; Mario-Luca Suvà; Karine Baumer; Paolo Provero; Ivan Stamenkovic; A TARBP2-Dependent miRNA Expression Profile Underlies Cancer Stem Cell Properties and Provides Candidate Therapeutic Reagents in Ewing Sarcoma. Cancer Cell 2012, 21, 807-821, 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.04.023.

- Elsa J. Sousa; Inês Graça; Tiago Baptista; Filipa Q. Vieira; Carlos Palmeira; Rui Henrique; Carmen Jerónimo; Enoxacin inhibits growth of prostate cancer cells and effectively restores microRNA processing. Epigenetics 2013, 8, 548-558, 10.4161/epi.24519.

- Julia Ramírez-Moya; León Wert-Lamas; Garcilaso Riesco-Eizaguirre; Pilar Santisteban; Impaired microRNA processing by DICER1 downregulation endows thyroid cancer with increased aggressiveness. Oncogene 2019, 38, 5486-5499, 10.1038/s41388-019-0804-8.

- Ubaldo Gioia; Sofia Francia; Matteo Cabrini; Silvia Brambillasca; Flavia Michelini; Corey W. Jones-Weinert; Fabrizio D’Adda Di Fagagna; Pharmacological boost of DNA damage response and repair by enhanced biogenesis of DNA damage response RNAs. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 6460, 10.1038/s41598-019-42892-6.

- Nathan S. Abell; Marvin Mercado; Tatiana Cañeque; Raphaël Rodriguez; Blerta Xhemalce; Click Quantitative Mass Spectrometry Identifies PIWIL3 as a Mechanistic Target of RNA Interference Activator Enoxacin in Cancer Cells. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2017, 139, 1400-1403, 10.1021/jacs.6b11751.

- Haruna Yamashiro; Mikiko C. Siomi; PIWI-Interacting RNA in Drosophila: Biogenesis, Transposon Regulation, and Beyond. Chemical Reviews 2017, 118, 4404-4421, 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00393.

- Lei Jiang; Wen-Jun Wang; Zhan-Wu Li; Xiao-Zhou Wang; Downregulation of Piwil3 suppresses cell proliferation, migration and invasion in gastric cancer. Cancer Biomarkers 2017, 20, 499-509, 10.3233/CBM-170324.

- Lan Li; Chaohui Yu; Hengjun Gao; Youming Li; Argonaute proteins: potential biomarkers for human colon cancer. BMC Cancer 2010, 10, 38-38, 10.1186/1471-2407-10-38.

- Shiguang Cao; Ruiying Sun; Wei Wang; Xia Meng; Yuping Zhang; Na Zhang; Shuanying Yang; RNA helicase DHX9 may be a therapeutic target in lung cancer and inhibited by enoxacin.. American journal of translational research 2017, 9, 674-682.

- Chih-Hung Chou; Nai-Wen Chang; Sirjana Shrestha; Sheng-Da Hsu; Yu-Ling Lin; Wei-Hsiang Lee; Chi-Dung Yang; Hsiao-Chin Hong; Ting-Yen Wei; Siang-Jyun Tu; et al.Tzi-Ren TsaiShu-Yi HoTing-Yan JianHsin-Yi WuPin-Rong ChenNai-Chieh LinHsin-Tzu HuangTzu-Ling YangChung-Yuan PaiChun-San TaiWen-Liang ChenChia-Yen HuangChun-Chi LiuShun-Long WengKuang-Wen LiaoWen-Lian HsuHsien-Da Huang miRTarBase 2016: updates to the experimentally validated miRNA-target interactions database. Nucleic Acids Research 2015, 44, D239-D247, 10.1093/nar/gkv1258.

- Yonit Hoffman; Yitzhak Pilpel; Moshe Oren; microRNAs and Alu elements in the p53-Mdm2-Mdm4 regulatory network. Journal of Molecular Cell Biology 2014, 6, 192-197, 10.1093/jmcb/mju020.

- Georgios Valianatos; Barbora Valcikova; Kateřina Growková; Amandine Verlande; Jitka Mlcochova; Lenka Radova; Monika Stetkova; Michaela Vyhnakova; Ondrej Slaby; Stjepan Uldrijan; et al. A small molecule drug promoting miRNA processing induces alternative splicing of MdmX transcript and rescues p53 activity in human cancer cells overexpressing MdmX protein. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0185801, 10.1371/journal.pone.0185801.

- Taylor C. Vracar; Jian Zuo; Jeongsu Park; Demyana Azer; Christy Mikhael; Sophia A. Holliday; Dontreyl Holsey; Guanghong Han; Lindsay VonMoss; John K. Neubert; et al.Wellington J. RodyEdward K. L. ChanL. Shannon Holliday Enoxacin and bis-enoxacin stimulate 4T1 murine breast cancer cells to release extracellular vesicles that inhibit osteoclastogenesis. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 16182, 10.1038/s41598-018-34698-9.

- Alicja Chrzanowska; Marta Struga; Piotr Roszkowski; Michał Koliński; Sebastian Kmiecik; Karolina Jałbrzykowska; Anna Zabost; Joanna Stefańska; Ewa Augustynowicz-Kopeć; Małgorzata Wrzosek; et al.Anna Bielenica The Effect of Conjugation of Ciprofloxacin and Moxifloxacin with Fatty Acids on Their Antibacterial and Anticancer Activity. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 6261, 10.3390/ijms23116261.

- Alicja Chrzanowska; Piotr Roszkowski; Anna Bielenica; Wioletta Olejarz; Karolina Stępień; Marta Struga; Anticancer and antimicrobial effects of novel ciprofloxacin fatty acids conjugates. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2019, 185, 111810, 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.111810.

- H F Dvorak; Leaky tumor vessels: consequences for tumor stroma generation and for solid tumor therapy.. Progress in clinical and biological research 1990, 354A, 317-30.

- Jr-Shiuan Yang; Eric C. Lai; Alternative miRNA Biogenesis Pathways and the Interpretation of Core miRNA Pathway Mutants. Molecular Cell 2011, 43, 892-903, 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.07.024.

- Thomas Maurin; Demián Cazalla; Jr-Shiuan Yang; Diane Bortolamiol-Becet; Eric C. Lai; RNase III-independent microRNA biogenesis in mammalian cells. RNA 2012, 18, 2166-2173, 10.1261/rna.036194.112.

- Jr-Shiuan Yang; Eric C. Lai; Dicer-independent, Ago2-mediated microRNA biogenesis in vertebrates. Cell Cycle 2010, 9, 4455-4460, 10.4161/cc.9.22.13958.

- Yong Xu; Fang Fang; Jiayou Zhang; Sajni Josson; William H. St. Clair; Daret K. St. Clair; miR-17* Suppresses Tumorigenicity of Prostate Cancer by Inhibiting Mitochondrial Antioxidant Enzymes. PLOS ONE 2010, 5, e14356, 10.1371/journal.pone.0014356.

- Munekazu Yamakuchi; Marcella Ferlito; Charles J. Lowenstein; miR-34a repression of SIRT1 regulates apoptosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2008, 105, 13421-13426, 10.1073/pnas.0801613105.

- Wei Wei; Yang Yang; Jian Cai; Kai Cui; Rong Xian Li; Huan Wang; Xiujuan Shang; Dong Wei; MiR-30a-5p Suppresses Tumor Metastasis of Human Colorectal Cancer by Targeting ITGB3. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry 2016, 39, 1165-1176, 10.1159/000447823.

- Jian Zhang; Yongkang Zhang; Xiaoyun Li; Hongbo Wang; Quan Li; Xiaofeng Liao; MicroRNA-212 inhibits colorectal cancer cell viability and invasion by directly targeting PIK3R3. Molecular Medicine Reports 2017, 16, 7864-7872, 10.3892/mmr.2017.7552.

- Roberto Gambari; Eleonora Brognara; Demetrios A. Spandidos; Enrica Fabbri; Targeting oncomiRNAs and mimicking tumor suppressor miRNAs: New trends in the development of miRNA therapeutic strategies in oncology (Review). International Journal of Oncology 2016, 49, 5-32, 10.3892/ijo.2016.3503.

- Maryam Nurzadeh; Mahsa Naemi; Shahrzad Sheikh Hasani; A comprehensive review on oncogenic miRNAs in breast cancer. Journal of Genetics 2021, 100, 1-21, 10.1007/s12041-021-01265-7.

- Elisa Penna; Francesca Orso; Daniela Taverna; miR-214 as a Key Hub that Controls Cancer Networks: Small Player, Multiple Functions. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 2015, 135, 960-969, 10.1038/jid.2014.479.

- Mengru Cao; Masahiro Seike; Chie Soeno; Hideaki Mizutani; Kazuhiro Kitamura; Yuji Minegishi; Rintaro Noro; Akinobu Yoshimura; Li Cai; Akihiko Gemma; et al. MiR-23a regulates TGF-β-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition by targeting E-cadherin in lung cancer cells. International Journal of Oncology 2012, 41, 869-875, 10.3892/ijo.2012.1535.

- Monireh Khordadmehr; Roya Shahbazi; Sanam Sadreddini; Behzad Baradaran; miR‐193: A new weapon against cancer. Journal of Cellular Physiology 2019, 234, 16861-16872, 10.1002/jcp.28368.

- Arata Itoh; David Adams; Wenting Huang; Yuehong Wu; Kritika Kachapati; Kyle J. Bednar; Patrick S. C. Leung; Weici Zhang; Richard A. Flavell; M. Eric Gershwin; et al.William M. Ridgway Enoxacin Up‐Regulates MicroRNA Biogenesis and Down‐Regulates Cytotoxic CD8 T‐Cell Function in Autoimmune Cholangitis. Hepatology 2021, 74, 835-846, 10.1002/hep.31724.

- Neil R. Smalheiser; Hui Zhang; Yogesh Dwivedi; Enoxacin Elevates MicroRNA Levels in Rat Frontal Cortex and Prevents Learned Helplessness. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2014, 5, 6, 10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00006.

- Xinbo Huang; Zhicong Chen; Yuchen Liu; RNAi-mediated control of CRISPR functions. Theranostics 2020, 10, 6661-6673, 10.7150/thno.44880.

- miRNA’s Nomenclature . miRBase. Retrieved 2022-7-1

More