Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 3 by Conner Chen and Version 2 by Conner Chen.

The development of low- or non-invasive screening tests for cancer is crucial for early detection. Saliva is an ideal biofluid containing informative components for monitoring oral and systemic diseases. Metabolomics has frequently been used to identify and quantify numerous metabolites in saliva samples, serving as novel biomarkers associated with various conditions, including cancers.

- oral cancer

- metabolomics

- saliva

1. Introduction

Oral cancer (OC) is a blanket term used to describe any cancer occurring in the oral cavity. In 2018, more than 350,000 new cases of OC and 170,000 deaths were recorded worldwide [1]. Tobacco usage, alcohol consumption, and human papillomavirus infection are the major risk factors for OC [2][3][4]. A recent study compared the incidence of OC in the 10 most populous countries over the past 30 years and reported declining trends in the annual age-standardized incidence rate of OC in Bangladesh, Brazil, Mexico, and the United States; however, increasing trends were observed in China, Indonesia, Pakistan, India, and Japan [5]. The 5-year overall survival rate of OC is approximately 50% [6]. To improve the prognosis and quality of life of patients, early detection of OC is essential [7].

The underlying epigenetic mechanisms and major risk factors of OC vary across countries. India accounts for one-third of the global OC cases, with 77,000 new OC cases and 52,000 related deaths annually [8]. Tobacco consumption is the main etiological factor. Most OC cases are diagnosed at advanced stages owing to delays in reporting to healthcare professionals [9]. Approximately 60–80% of the patients with OC diagnosed at late-stage Early detection can improve treatment efficacy and prognosis. Although various methods are available for screening, visual examination is the most commonly used owing to its low cost [10]. However, diagnosing lesions in the initial stage and differentiating them from inflammatory conditions remain challenging.

Despite the declining trend of tobacco use in Japan, the incidence of OC has increased [11]. Similar to the global trend, many patients are diagnosed with late-stage OC. In Japan, nationwide screening of five cancers (gastric, colon, and lung cancers for both sexes and breast and cervical cancers for women) is conducted annually or every other year. Insufficient screening is among the reasons for the increasing trend of OC. Therefore, the development of a new cost-effective screening system for OC is necessary.

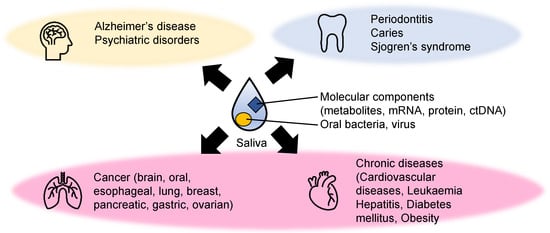

Saliva is a mixture of biofluids and plays vital roles in oral homeostasis. Other functions of saliva include lubrication, digestion, buffering, taste, tooth protection, and immune defense by protecting against bacteria, viruses, and fungi. Saliva consists of various cellular and molecular components, such as transudate of the oral mucosa, desquamated oral epithelial cells, blood cells, oral bacteria, proteins, metabolites, and inorganic ions (Figure 1). Furthermore, it is mainly secreted from three major salivary glands (parotid, submandibular, and sublingual glands) and other minor glands. It also contains various components which originate from other sources, such as gingival crevicular fluid. Overall, these components make saliva an ideal biofluid for detecting various diseases.

Figure 1. Examples of diseases detected using metabolite biomarkers. The biomarkers of mental illnesses (yellow), dental diseases (light blue), and various systematic diseases (light pink) related to metabolic abnormalities have been explored.

There are several advantages of using saliva for cancer detection. First, a positive correlation has been reported between salivary and plasma metabolite levels, such as those of glucose, pyruvate, and lactate [12][13], indicating that salivary metabolites provide biological information. Second, saliva is the most readily available biofluid, and its collection requires minimal training [14]. Third, analysis of saliva samples is convenient owing to the noninfectious collection process, easy transportation, and disposable nature [15]. Fourth, the saliva metabolite profile of each individual is affected by diet compared to that of urine collected from identical individuals [16]. Therefore, several cancer biomarkers have been identified using salivary omics technologies.

2. Metabolite Measurement Technologies

The word metabolomics was coined by merging two terms—omics and metabolites. Therefore, it is expected to refer to an analytical method that measures all metabolites. However, no single method can be used to analyze all metabolites because of the large diversity of chemical structures of metabolites in biological samples [17]. Therefore, various methods have been developed, and each technique has its own advantages and disadvantages. Various metabolite separation and detection systems have also been used to analyze metabolites in saliva samples. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) is the most frequently used method [18]. Compared to mass spectrometry (MS), NMR has higher reproducibility and minimal preparation for any sample type [19]. Pretreatment of the saliva, a viscous liquid, is also a simple process [20]. This feature is a definitive advantage as it minimizes the chances of causing unexpected errors. NMR has enabled identification of pattern changes in salivary metabolomic profiles, i.e., metabolic signature, to distinguish between patients with cancer and HCs. Some applications of salivary metabolomics explored using NMR include the detection of OSCC [21][22], head and neck squamous cell carcinoma [23], and glioblastoma [24]. In addition to cancer, hepatitis B infection [25], Parkinson’s disease [26], and Alzheimer’s disease [27] have been analyzed. MS is another a major metabolite detection system with high sensitivity. It consumes a small volume of samples and enables the identification and quantification of hundreds of metabolites simultaneously [19]. However, direct injection to MS cannot separate the metabolites with the same m/z (mass divided by charge number) value, such as leucine and isoleucine; therefore, a separation system is usually used before MS. GC-MS allows the quantification volatile compounds and the profiling of non-volatile metabolites by derivatization, which was used to analyze OSCC samples [28]. Liquid chromatography (LC)-MS has been used for both non-targeted and targeted analyses of salivary metabolites. For non-targeted analyses, hydrophilic metabolites, such as γ-aminobutyric acid, phenylalanine, valine, and lactic acid, of saliva samples of OC patients were analyzed [21]. A wide variety of metabolites, such as oligopeptides, phosphatidylcholine, and glycerophospholipids, were analyzed in the saliva samples of patients with breast cancer [29][30]. For targeted analyses, salivary OSCC biomarkers, such as choline, betaine, pipecolinic acid, and carnitine, were quantified [31]. Salivary polyamines were also analyzed as known biomarkers for breast cancer [32]. Capillary electrophoresis (CE)-MS was used for hydrophilic metabolite profiling of saliva samples of OC [33][34][35][36][37], breast cancer [38], and pancreatic cancer (PC) [39]. Comparisons of NMR and MS for analyzing saliva samples for OC biomarker discoveries have been previously conducted [40][41]. Both reviews claimed the necessity of standardization of sample collection and the processing of measuring data. The simultaneous use of NMR and LC-MS to analyze salivary metabolites succeeded in the coverage expansion of the observed metabolite [42], enhancing the opportunity to find biomarkers related to the focused phenotype.3. Discrimination Methods

To identify biomarkers, conventional univariate analyses, such as the Student’s t-test and the Mann–Whitney test for two-group comparisons, have been used in previous studies. Additionally, multivariate analyses were frequently used to analyze the similarity and the difference of overall metabolite profiles. As unsupervised methods, principal component analysis (PCA) and hierarchical clustering analysis have been performed. For example, PCA was used to assess the relative strength of the effects of multiple factors, such as inter and intraday variations, on salivary metabolomics [43]. Clustering was used to find new subgroups of a disease group based on the observed metabolomic profiles [44]. These methods help find outliers, assess the quality of samples, and form the groups used in subsequent analyses. To discriminate a disease group from other groups, such as OC from HC, a combination of multiple metabolite concentration patterns was used (Table 1). MLR is one of the conventional multivariable methods. It uses minimal independent metabolite sets by eliminating multicollinearity problems [34][36][45]. Lasso regression model solved the multicollinearity problem [46]. Partial least squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) is also frequently used to discriminate against multiple groups, enabling the ranking of the metabolite’s contribution to the discrimination. For example, discrimination among OSCC, OLK, and HC was conducted using this method [21]. Random forest, a classification machine learning (ML) model that leverages multiple decision trees [47], and alternative decision trees [38] have also been used to discriminate a group from the others. The most important concern is rigorous validation of the generalization ability to eliminate overfitting. Cross-validation is commonly used in a single cohort, while accuracy evaluation using an independent cohort provides a more rigorous validation [46].4. Standard Operating Protocols (SoP)

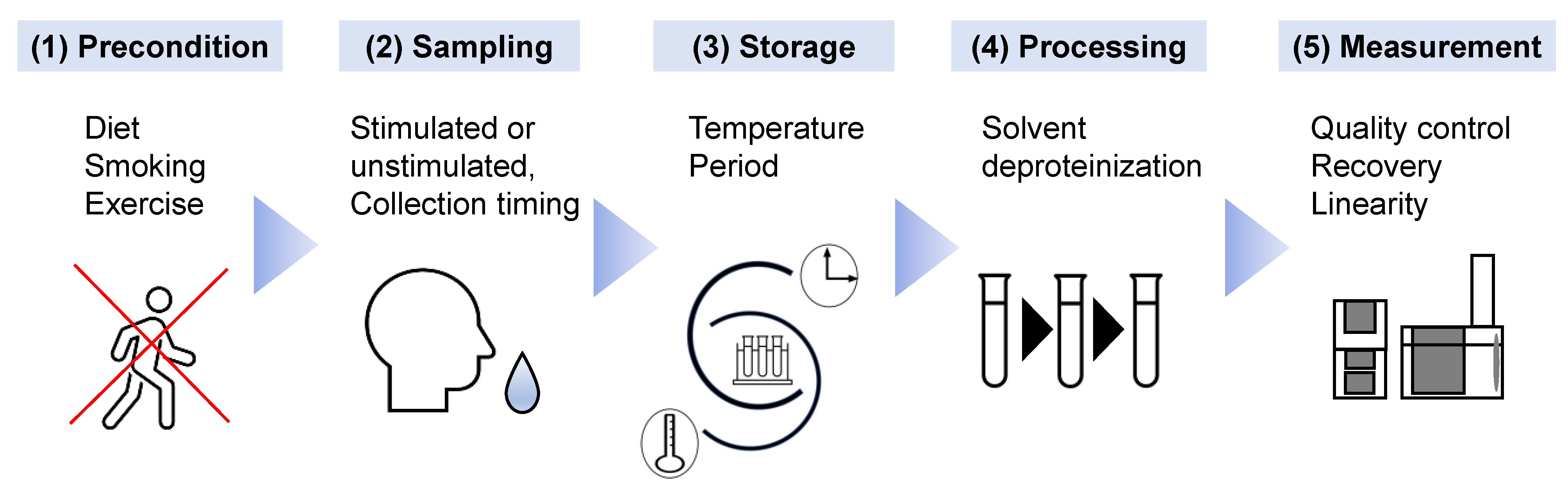

The discovery and validation of biomarkers are the initial steps to establish new screening methods. A standard protocol for working with saliva samples should be determined to enhance reproducibility. The methods for preconditioning, sample collection, storage, preprocessing, measurement, and data analysis should be standardized [48]. The effect of inter-day and intra-day variations on salivary metabolomics has been analyzed [43], and no significant salivary flow was observed in the comparisons. The stimulated saliva showed larger variations in metabolomic profiles than the unstimulated saliva. The time period between the last diet and sample collection also affected salivary metabolomic profiles [37]. As expected, longer fasting conditions before sample collection improved the discrimination ability of the OC biomarkers. Normalization of overall concentration with the total contents of amino acids decreased the variations due to fasting conditions. Stimulation of the oral cavity, for example, using tobacco and mouthwash, also affected the final results [49], with stimulated and unstimulated saliva having different metabolomic profiles [50]. Taken together, the longer the fasting period, the more consistent the use of stimulated or unstimulated saliva samples. Thus, a restriction affecting the oral cavity should be defined as part of the SoP. The effect of storage conditions on the quantified concentration of metabolite biomarkers was also analyzed [31]. Variations between short-term storage at room temperature (up to 24 h) and long-term storage at −35 °C (up to 1 month) of four OC biomarkers, such as choline and betaine, were detected. Storage and preprocessing also affected the polyamine profiles in saliva [51]. The artificially generated noise according to the maximum variations observed during storage and preprocessing enabled the estimation of possible deterioration of discrimination abilities of the biomarkers. Such analyses would assit in the stablishment of SoP in the clinical settings. Because it is not necessarily limited to salivary metabolomics, MS-based metabolomics required better quality control than NMR-based ones [19]. Therefore, quality assessment for each processing step and a control method were developed to normalize the quantified data to ultimately eliminate unexpected bias in multiple batch measurements [52]. Along with these standardizations, the development of an automatic pipeline is also a reasonable approach [46]. The establishment of a rigorous protocol will likely yield reproducible results; however, it may hinder the widespread use of salivary tests (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The factors influencing salivary metabolomics that require the establishment of standard operating procedures are shown. (1) As preconditions before saliva collection, the diet, smoking behavior, and intensive exercise of subjects should be restricted, as they potentially affect salivary metabolites. (2) To eliminate diurnal variation, stipulated timing of saliva collection, e.g., 9:00–11:00 am, should be implemented. The selection of stimulated or unstimulated saliva is vital. (3) The temperature and duration of storage of the saliva samples should also be standardized. (4) Chemicals used as solvents and the methodology for deproteinization should be selected accurately. (5) Quality assessment of the measurement device using quality control samples is vital to eliminate unexpected bias.

References

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2018: Globocan Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. Ca Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424.

- Zhao, D.; Xu, Q.G.; Chen, X.M.; Fan, M.W. Human Papillomavirus as an Independent Predictor in Oral Squamous Cell Cancer. Int. J. Oral. Sci. 2009, 1, 119–125.

- Asthana, S.; Labani, S.; Kailash, U.; Sinha, D.N.; Mehrotra, R. Association of Smokeless Tobacco Use and Oral Cancer: A Systematic Global Review and Meta-Analysis. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2019, 21, 1162–1171.

- Miranda-Filho, A.; Bray, F. Global Patterns and Trends in Cancers of the Lip, Tongue and Mouth. Oral Oncol. 2020, 102, 104551.

- Zhang, S.Z.; Xie, L.; Shang, Z.J. Burden of Oral Cancer on the 10 Most Populous Countries from 1990 to 2019: Estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Int. J. Env.. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 875.

- Warnakulasuriya, S. Global Epidemiology of Oral and Oropharyngeal Cancer. Oral Oncol. 2009, 45, 309–316.

- Sciubba, J.J. Oral Cancer. The Importance of Early Diagnosis and Treatment. Am. J. Clin. Derm.. 2001, 2, 239–251.

- Borse, V.; Konwar, A.N.; Buragohain, P. Oral Cancer Diagnosis and Perspectives in India. Sens. Int. 2020, 1, 100046.

- Akram, M.; Siddiqui, S.A.; Karimi, A.M. Patient Related Factors Associated with Delayed Reporting in Oral Cavity and Oropharyngeal Cancer. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2014, 5, 915–919.

- Mummudi, N.; Agarwal, J.P.; Chatterjee, S.; Mallick, I.; Ghosh-Laskar, S. Oral Cavity Cancer in the Indian Subcontinent - Challenges and Opportunities. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 31, 520–528.

- Kawakita, D.; Oze, I.; Iwasaki, S.; Matsuda, T.; Matsuo, K.; Ito, H. Trends in the Incidence of Head and Neck Cancer by Subsite between 1993 and 2015 in Japan. Cancer Med. 2022, 11, 1553–1560.

- Englander, H.; Jeffay, A.; Fuller, J.; Chauncey, H. Glucose Concentrations in Blood Plasma and Parotid Saliva of Individuals with and without Diabetes Mellitus. J. Dent. Res. 1963, 42, 1246–1246.

- Kelsay, J.L.; Behall, K.M.; Holden, J.M.; Crutchfield, H.C. Pyruvate and Lactate in Human Blood and Saliva in Response to Different Carbohydrates. J. Nutr. 1972, 102, 661–666.

- Gardner, A.; Carpenter, G.; So, P.W. Salivary Metabolomics: From Diagnostic Biomarker Discovery to Investigating Biological Function. Metabolites 2020, 10, 47.

- Khurshid, Z.; Zohaib, S.; Najeeb, S.; Zafar, M.S.; Slowey, P.D.; Almas, K. Human Saliva Collection Devices for Proteomics: An Update. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 846.

- Wallner-Liebmann, S.; Tenori, L.; Mazzoleni, A.; Dieber-Rotheneder, M.; Konrad, M.; Hofmann, P.; Luchinat, C.; Turano, P.; Zatloukal, K. Individual Human Metabolic Phenotype Analyzed by 1H NMR of Saliva Samples. J. Proteome Res. 2016, 15, 1787–1793.

- Monton, M.R.; Soga, T. Metabolome Analysis by Capillary Electrophoresis-Mass Spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2007, 1168, 237–246.

- Ranjan, R.; Sinha, N. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR)-Based Metabolomics for Cancer Research. NMR Biomed. 2019, 32, e3916.

- Vignoli, A.; Ghini, V.; Meoni, G.; Licari, C.; Takis, P.G.; Tenori, L.; Turano, P.; Luchinat, C. High-Throughput Metabolomics by 1D NMR. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2019, 58, 968–994.

- Gardner, A.; Parkes, H.G.; Carpenter, G.H.; So, P.W. Developing and Standardizing a Protocol for Quantitative Proton Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (1H NMR) Spectroscopy of Saliva. J. Proteome Res. 2018, 17, 1521–1531.

- Wei, J.; Xie, G.; Zhou, Z.; Shi, P.; Qiu, Y.; Zheng, X.; Chen, T.; Su, M.; Zhao, A.; Jia, W. Salivary Metabolite Signatures of Oral Cancer and Leukoplakia. Int. J. Cancer 2011, 129, 2207–2217.

- Lohavanichbutr, P.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, P.; Gu, H.; Nagana Gowda, G.A.; Djukovic, D.; Buas, M.F.; Raftery, D.; Chen, C. Salivary Metabolite Profiling Distinguishes Patients with Oral Cavity Squamous Cell Carcinoma from Normal Controls. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204249.

- Mikkonen, J.J.W.; Singh, S.P.; Akhi, R.; Salo, T.; Lappalainen, R.; González-Arriagada, W.A.; Ajudarte Lopes, M.; Kullaa, A.M.; Myllymaa, S. Potential Role of Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy to Identify Salivary Metabolite Alterations in Patients with Head and Neck Cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 16, 6795–6800.

- García-Villaescusa, A.; Morales-Tatay, J.M.; Monleón-Salvadó, D.; González-Darder, J.M.; Bellot-Arcis, C.; Montiel-Company, J.M.; Almerich-Silla, J.M. Using NMR in Saliva to Identify Possible Biomarkers of Glioblastoma and Chronic Periodontitis. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0188710.

- Gilany, K.; Mohamadkhani, A.; Chashmniam, S.; Shahnazari, P.; Amini, M.; Arjmand, B.; Malekzadeh, R.; Nobakht Motlagh Ghoochani, B.F. Metabolomics Analysis of the Saliva in Patients with Chronic Hepatitis B Using Nuclear Magnetic Resonance: A Pilot Study. Iran J. Basic Med. Sci. 2019, 22, 1044–1049.

- Kumari, S.; Goyal, V.; Kumaran, S.S.; Dwivedi, S.; Srivastava, A.; Jagannathan, N. Quantitative Metabolomics of Saliva Using Proton NMR Spectroscopy in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease and Healthy Controls. Neurol. Sci. 2020, 41, 1201–1210.

- Yilmaz, A.; Geddes, T.; Han, B.; Bahado-Singh, R.O.; Wilson, G.D.; Imam, K.; Maddens, M.; Graham, S.F. Diagnostic Biomarkers of Alzheimer’s Disease as Identified in Saliva Using 1H NMR-Based Metabolomics. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2017, 58, 355–359.

- de Sá Alves, M.; de Sá Rodrigues, N.; Bandeira, C.M.; Chagas, J.F.S.; Pascoal, M.B.N.; Nepomuceno, G.; da Silva Martinho, H.; Alves, M.G.O.; Mendes, M.A.; Dias, M.; et al. Identification of Possible Salivary Metabolic Biomarkers and Altered Metabolic Pathways in South American Patients Diagnosed with Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Metabolites 2021, 11, 650.

- Zhong, L.; Cheng, F.; Lu, X.; Duan, Y.; Wang, X. Untargeted Saliva Metabonomics Study of Breast Cancer Based on Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography Coupled to Mass Spectrometry with Hilic and Rplc Separations. Talanta 2016, 158, 351–360.

- Xavier Assad, D.; Acevedo, A.C.; Cançado Porto Mascarenhas, E.; Costa Normando, A.G.; Pichon, V.; Chardin, H.; Neves Silva Guerra, E.; Combes, A. Using an Untargeted Metabolomics Approach to Identify Salivary Metabolites in Women with Breast Cancer. Metabolites 2020, 10, 506.

- Wang, Q.; Gao, P.; Wang, X.; Duan, Y. Investigation and Identification of Potential Biomarkers in Human Saliva for the Early Diagnosis of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Clin. Chim. Acta 2014, 427, 79–85.

- Tsutsui, H.; Mochizuki, T.; Inoue, K.; Toyama, T.; Yoshimoto, N.; Endo, Y.; Todoroki, K.; Min, J.Z.; Toyo’oka, T. High-Throughput Lc-Ms/Ms Based Simultaneous Determination of Polyamines Including N-Acetylated Forms in Human Saliva and the Diagnostic Approach to Breast Cancer Patients. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 11835–11842.

- Ohshima, M.; Sugahara, K.; Kasahara, K.; Katakura, A. Metabolomic Analysis of the Saliva of Japanese Patients with Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 2017, 37, 2727–2734.

- Ishikawa, S.; Sugimoto, M.; Edamatsu, K.; Sugano, A.; Kitabatake, K.; Iino, M. Discrimination of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma from Oral Lichen Planus by Salivary Metabolomics. Oral. Dis. 2020, 26, 35–42.

- Ishikawa, S.; Hiraka, T.; Kirii, K.; Sugimoto, M.; Shimamoto, H.; Sugano, A.; Kitabatake, K.; Toyoguchi, Y.; Kanoto, M.; Nemoto, K.; et al. Relationship between Standard Uptake Values of Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography and Salivary Metabolites in Oral Cancer: A Pilot Study. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3958.

- Ishikawa, S.; Sugimoto, M.; Kitabatake, K.; Sugano, A.; Nakamura, M.; Kaneko, M.; Ota, S.; Hiwatari, K.; Enomoto, A.; Soga, T.; et al. Identification of Salivary Metabolomic Biomarkers for Oral Cancer Screening. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31520.

- Ishikawa, S.; Sugimoto, M.; Kitabatake, K.; Tu, M.; Sugano, A.; Yamamori, I.; Iba, A.; Yusa, K.; Kaneko, M.; Ota, S.; et al. Effect of Timing of Collection of Salivary Metabolomic Biomarkers on Oral Cancer Detection. Amino Acids 2017, 49, 761–770.

- Murata, T.; Yanagisawa, T.; Kurihara, T.; Kaneko, M.; Ota, S.; Enomoto, A.; Tomita, M.; Sugimoto, M.; Sunamura, M.; Hayashida, T.; et al. Salivary Metabolomics with Alternative Decision Tree-Based Machine Learning Methods for Breast Cancer Discrimination. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2019, 177, 591–601.

- Asai, Y.; Itoi, T.; Sugimoto, M.; Sofuni, A.; Tsuchiya, T.; Tanaka, R.; Tonozuka, R.; Honjo, M.; Mukai, S.; Fujita, M.; et al. Elevated Polyamines in Saliva of Pancreatic Cancer. Cancers 2018, 10, 43.

- Hyvärinen, E.; Savolainen, M.; Mikkonen, J.J.W.; Kullaa, A.M. Salivary Metabolomics for Diagnosis and Monitoring Diseases: Challenges and Possibilities. Metabolites 2021, 11, 587.

- Jain, N.S.; Dürr, U.H.; Ramamoorthy, A. Bioanalytical Methods for Metabolomic Profiling: Detection of Head and Neck Cancer, Including Oral Cancer. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2015, 26, 407–415.

- Figueira, J.; Gouveia-Figueira, S.; Öhman, C.; Lif Holgerson, P.; Nording, M.L.; Öhman, A. Metabolite Quantification by NMR and Lc-Ms/Ms Reveals Differences between Unstimulated, Stimulated, and Pure Parotid Saliva. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2017, 140, 295–300.

- Kawanishi, N.; Hoshi, N.; Masahiro, S.; Enomoto, A.; Ota, S.; Kaneko, M.; Soga, T.; Tomita, M.; Kimoto, K. Effects of Inter-Day and Intra-Day Variation on Salivary Metabolomic Profiles. Clin. Chim. Acta 2019, 489, 41–48.

- Na, H.S.; Kim, S.; Kim, S.; Yu, Y.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, J.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Chung, J. Molecular Subgroup of Periodontitis Revealed by Integrated Analysis of the Microbiome and Metabolome in a Cross-Sectional Observational Study. J. Oral Microbiol. 2021, 13, 1902707.

- Sugimoto, M.; Wong, D.T.; Hirayama, A.; Soga, T.; Tomita, M. Capillary Electrophoresis Mass Spectrometry-Based Saliva Metabolomics Identified Oral, Breast and Pancreatic Cancer-Specific Profiles. Metabolomics 2010, 6, 78–95.

- Song, X.; Yang, X.; Narayanan, R.; Shankar, V.; Ethiraj, S.; Wang, X.; Duan, N.; Ni, Y.H.; Hu, Q.; Zare, R.N. Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Diagnosed from Saliva Metabolic Profiling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Usa 2020, 117, 16167–16173.

- Kim, S.; Kim, H.J.; Song, Y.; Lee, H.A.; Kim, S.; Chung, J. Metabolic Phenotyping of Saliva to Identify Possible Biomarkers of Periodontitis Using Proton Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2021, 48, 1240–1249.

- Sugimoto, M.; Ota, S.; Kaneko, M.; Enomoto, A.; Soga, T. Quantification of Salivary Charged Metabolites Using Capillary Electrophoresis Time-of-Flight-Mass Spectrometry. Bio Protoc. 2020, 10, e3797.

- Sugimoto, M.; Saruta, J.; Matsuki, C.; To, M.; Onuma, H.; Kaneko, M.; Soga, T.; Tomita, M.; Tsukinoki, K. Physiological and Environmental Parameters Associated with Mass Spectrometry-Based Salivary Metabolomic Profiles. Metabolomics 2013, 9, 454–463.

- Okuma, N.; Saita, M.; Hoshi, N.; Soga, T.; Tomita, M.; Sugimoto, M.; Kimoto, K. Effect of Masticatory Stimulation on the Quantity and Quality of Saliva and the Salivary Metabolomic Profile. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0183109.

- Tomita, A.; Mori, M.; Hiwatari, K.; Yamaguchi, E.; Itoi, T.; Sunamura, M.; Soga, T.; Tomita, M.; Sugimoto, M. Effect of Storage Conditions on Salivary Polyamines Quantified Via Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12075.

- Aristizabal-Henao, J.J.; Lemas, D.J.; Griffin, E.K.; Costa, K.A.; Camacho, C.; Bowden, J.A. Metabolomic Profiling of Biological Reference Materials Using a Multiplatform High-Resolution Mass Spectrometric Approach. J. Am. Soc. Mass. Spectrom. 2021, 32, 2481–2489.

More