Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Weixuan Chen and Version 2 by Dean Liu.

China’s new-type urbanisation, as a national strategy, is one of the reasons why the leap in development has been made in the last decade. Existing studies mainly focus on the status and outcomes of china’s new-type urbanisation while stressing not enough the overlooked aspects of new-type urbanisation policies that are currently in use.

- policy implementations

- new-type urbanisation

- population

1. Global Urban Development Issues and Urbanisation

Nowadays, the world faces many fundamental sustainability challenges in several domains. Energy supply, for example, is confronted with a rapid depletion of natural resources, air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions, nuclear risks, uncertainties related to its security of supply, and energy poverty [1]. Water supply and sanitation systems have to tackle a broad range of problems related to water scarcity, insufficient access in low-income countries, and extreme events such as flooding, earthquakes, and micro-pollutants [2]. The transportation sector is challenged by congestion, local air pollution, fossil fuel depletion and CO2 emissions, and the risk of accidents, and other sectors such as agriculture, food system, and education, must cope with similar challenges [3]. While most of these challenges are related to environmental and social issues, economic problems are pressing as well. Existing infrastructure systems in many parts of the world are confronted with huge financial needs in terms of infrastructure renewal and expansion, which seem even more daunting in times of financial crisis and public budget overruns [4][5][4,5]. In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic is reshaping the world order of economy and politics [6]. This event has slowed down economic growth, increased unemployment, and raised poverty and hunger [7]. The decline in the world gross product could lead to an additional 25 million unemployed people worldwide [7]. Hunger will also increase, with the number of people facing acute food insecurity doubling to about 265 million by the end of 2020 [8]. A growing number of scholars and policymakers believe that it is urgent to deal with global climate change and other socio-environmental problems. These problems are threatening global sustainable development.

Cities are the key to global sustainability endeavours, as they are the largest consumer of resources and contribute the largest proportion of the world’s total greenhouse gases emissions [9][10][9,10]. As a consequence of the urbanisation trend, energy demands, building construction, waste and water services, and industrial processes are centred in and around the cities [11]. To deal with these problems, countries worldwide have reached a basic consensus on the establishment and application of a low-carbon economy, and some developed countries have already achieved this [12]. The social, spatial, and economic structure change occurred in the process, accompanied by urbanisation. The level of urbanisation is reflected by the urban population rate [13][14][13,14]. China’s urbanisation rate was 63.89% in 2020, showing that Chinese cities are still in a phase of rapid development [15]. The first half of the accelerated urbanisation phase (30–50%) took 60 years in Britain, Germany, and France, while China took only 15 years. The second half of the accelerated urbanisation phase (50–70%) took 60 years in the UK and Germany, 40 years in France and the United States, and 15 years in Japan. Based on the forecast of a faster urbanisation rate of 1.2% per year, China’s urbanization rate will take about 15 years to increase from 50% to 70%, which is much faster than Europe and the United States and comparable to Japan. However, there is, at present, a huge gap between the level of urbanisation in China and that in developed economies such as Japan, the United States, and the United Kingdom.

2. China’s Urbanisation Process

As the world fully enters the era of planetary urbanisation, China becomes increasingly important not just within China but globally [16][17][18,19]. Urban development in China is unlike that in the west and many other developing countries. Compared with many cities in Western countries, which often share a broadly similar economic and political history among them (free market or mixed economy, social-democratic systems, etc.), cities in China are very different both economically and, above all, politically [17][19]. Nevertheless, while the previous literature borrows many concepts from the Western urban studies literature, comparisons with cities elsewhere are short-circuited by the argument that Chinese cities are unique [18][20]. China is where one very important vision is unfolding when looking at the changing nature of global urban development [17][19]. China’s urbanisation plays an important and unique role in global development. The crucial position of the role of China’s urbanisation in global urbanisation has been raised [19][21]. This has a profound impact on China’s economy as well as the world economy [20][22]. Furthermore, China’s urbanisation is too unique to easily subsume into standard discussions about urban development and urban change. On the one hand, cities in China have received millions of rural migrants [19][21]. On the other hand, China’s urban area has increased rapidly, with large areas of farmlands converted into urban use, named in-situ urbanisation [21][23]. As such, China’s urbanisation issues should be separately explored based on its special institutional context and embeddedness.

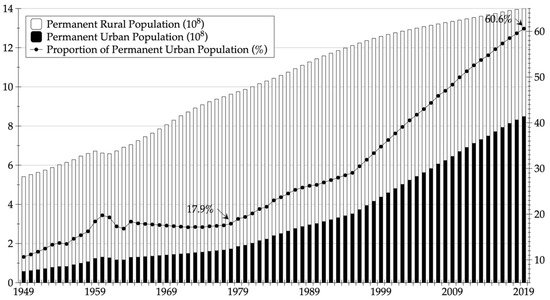

Since the founding of New China in 1949, the central government has issued regulation policies to guide urbanisation in different periods. An important policy, Reform and Opening up, published in December 1978, drove urbanisation into a rapid stage. More than 600 million people moved from rural areas to cities, and the proportion of PUP increased from 17.92% in 1978 to 63.89% in 2020 [22][16].

Influenced by the fluctuation of these policies in different periods, China’s urbanisation rate has shown a fluctuating change since 1949. As seen in Figure 1, the rate experienced a period of steady improvement in the 1950s, rising from 10.64% in 1949 to 19.75% in 1960, followed by a rapid decline and 20-year stagnation of development. By the beginning of Reform and Opening up in 1978, this dropped to 17.92%. Subsequently, under incentives of sustained policies, this kept rising, capped by 28.62% in 1994, and the growth rate in the later period was significantly faster than that in the earlier period. From 1978 to 1994, the rate grew at an average annual rate of 0.67%, while from 1994 to 2012, it grew at an average annual rate of 1.33%, which was twice as fast as the previous period. However, problems in the process of rapid urbanisation were gradually prominent. For example, many cities in China were faced with severe environmental degradation, traffic congestion, rapidly rising housing prices, and urban vulnerability barriers. The urban sprawl caused by the land-revenue system challenged to fix the economic benefits brought by population and industrial agglomeration, resulting in huge environmental costs and fragmented construction land [23][24]. The main effect was that the population density of most cities in China decreased, contrary to the trend of other East Asian countries [24][25]. If this path of urbanisation were to continue, the lock-in effects of land-use decisions and urban infrastructure choices would lead to further environmental, economic, and social degradation [25][26]. China’s urbanisation thus needed to solve those problems through policy regulation.

3. China’s New-Type Urbanisation

The 18th Communist Party of China (CPC) National Congress in 2012 put forward the concept of new-type urbanisation. The human-based urbanisation was emphasised in the subsequent National New-type Urbanisation Plan (2014–2020) (NUP) [26][27]. Both the 19th CPC National Congress and the Central Economic Work Conference pointed out that the construction of socialism with Chinese characteristics and economic development had been entering a new stage and that the national economy was transitioning from high-speed to high-quality development. The NUP initialised a new approach to urbanisation in China [27][28]. This was an important driving force for economic development and social reform, optimising the structure of the urban scale and improving industry development [28][29]. Furthermore, the 14th Five-year Plan emphasised “improving the quality and effectiveness of urbanisation” and “deepening the human-based new-type urbanisation strategy” from 2021 to 2025.

One the one hand, existing studies focus on the status and outcomes of China’s new-type urbanisation. For example, Zhou and Li claimed that it is an important driving force for China’s economic development and social reform [29][30]. It favoured optimisation of the structure of the urban scale, sped up the transition and upgrade of industries in core cities, and enhanced the functions of cities [28][29]. It initialised new approaches to urbanisation in China [27][30][31][32][28,31,32,33]. In other words, it is not only a new national urbanisation principle and policy but is also a new stage of China’s development [31][32]. On the other hand, policy guidance has an important influence on China’s urbanisation [33][34]. The policy, as a kind of behaviour rule closely related to socio-economic actions [34][35], is an important driving force and guarantee [35][36]. Its influence on urbanisation is greater than economic factors because political leaders and government macro-management play a decisive role in this process [36][37]. The existing literature, however, does not stress enough the overlooked aspects of the new-type urbanisation policies that are currently in use.

4. Key Elements in Urbanisation

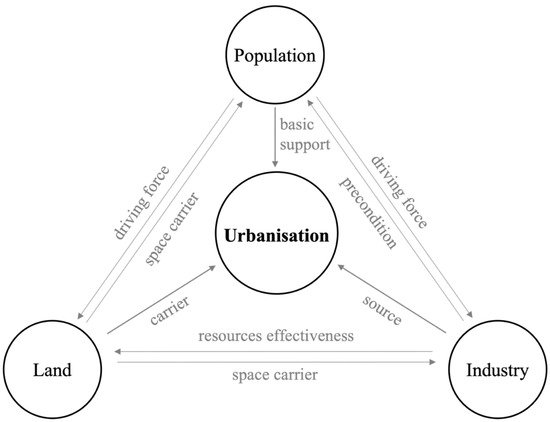

The relationship between population, land, and industry is a significant foundation for assessing urbanisation. The core of urbanisation is the non-agricultural transition of population, land, and industry [37][38][39][38,39,40]. As a macro-level system, urbanisation includes the meso-level subsystems of population, land, and industry, which are the basic supports, carriers, and sources of such development, respectively [40][41] (see Figure 2). The rate of the population to the total population represents different stages of urbanisation [41][42]. As property, living space, economic space, and place, the land is the core of urbanisation [42][43]. Industrial development, which is the foundation, constitutes the basic environmental and social conditions for modern economic development and the core content of improving residents’ livelihood and life quality [39][40].

Figure 2. A conceptual framework of the three key elements of urbanisation.

These subsystems are not separated. Mutual correlations, impacts, and restrictive relationships among population, land, and industrial urbanisation have been stated in the existing studies [40][43][41,44]. The flow of urban-rural population is a significant driving force for urban land expansion and industrial development [44][45]. Land urbanisation provides a space carrier for urban population growth and industrialisation [40][41]. Industrial urbanisation is the precondition of urban population and built-up area agglomeration [39][40]. In other words, because of changes in industrial structure and economic development, the demand for labour drives the migration of the rural population and multiplies the demand for construction land [45][46]. Furthermore, urbanisation should be examined not only its continuity from the historical point of view but also its unique particularity from the era point of view [46][47]. China’s urbanisation has been confirmed as an agglomeration process of population, built-up land, and industry in urban areas [44][47][48][45,48,49]. Additionally, the focus of new-type urbanisation is to integrate the spatial distribution of registered population, construction land, and secondary and tertiary industries Hence, if reswearchers want to understand the implementations of China’s new-type urbanisation, three key elements and their interactions provide an antecedent perspective.