TENG-Based Self-Powered Neuroprosthetics is a neuroprosthetic system using a triboelectric nanogenerator as the power source to generator the current pulses required for neural stimulations. The thin-film triboelectric nanogenerator can be attached onto the heart or buried under the skin to convert the mechanical energy from the movement of organs, such as heart beat, or the hand tapping onto the skin to electrical current pulses. This system is promising to realize a fully self-powered neural modulation with much reduced device complexity.

- Triboelectric nanogenerator

- Self-Powered Neuroprosthetics

- thin-film TENG device

- high-frequency switch

- bennet doubler conditioning circuit

1. Introduction

Neuroprosthetics is a powerful toolkit, for clinical interventions of various diseases, affecting the central nervous or peripheral nervous systems by electrically stimulating different neuronal structures [1]. Deep brain stimulation (DBS), based on the electrical stimulation of deep structures within the brain, is clinically used for symptomatic treatment of motor-related disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease, dystonia, and tremor, and it is also under clinical development for other drug-resistant neurological disorders, such as depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and others [2]. Electrical stimulation of the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system (PNS) can also be achieved by implanted neuroprosthetic devices in the spinal cord or peripheral nerves and muscles to restore sensory and motor function in a novel and promising field of therapeutic interventions termed “bioelectronics” [3,4,5,6,7][3][4][5][6][7]. To prolong the lifetime of the implanted devices, researchers have invested enormous enthusiasm and energy to develop the power sources for them [8,9,10,11][8][9][10][11]. One of the primary strategies is harvesting power from organs or the surrounding environment, which is also called a self-powered method. Currently, there are six major research directions for achieving this self-powered method by harvesting energy from our own body. Triboelectric nanogenerators (TENGs) and piezoelectric nanogenerators harvest energy from the motion of organs; optical devices, ultrasound devices, and electromagnetic coils receive energy wirelessly by a transcutaneous approach; and biofuel cells extract energy from the redox reaction of glucose and electrolytes in the gastrointestinal tract [12]. Among all these methods, a TENG is the onlymethod to achieve direct nerve stimulations [13,14[13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21],15,16,17,18,19,20,21], showing its capability in the realization of a self-powered neuroprosthetic system in the future, which is far beyond the application of energy harvesting and self-powered physical and chemical sensing [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50][51][52][53][54][55].

2. The Development of Triboelectric Nanogenerator (TENG)-Based Self-Powered Nerve Stimulation

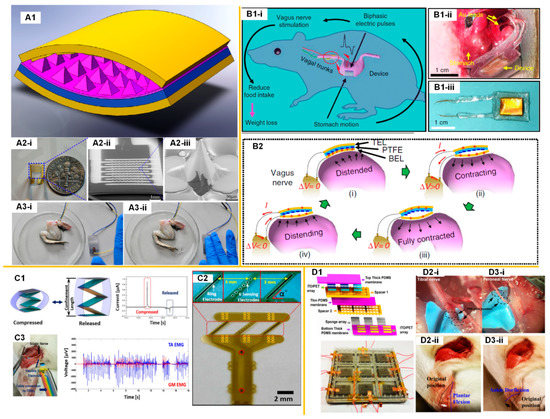

The feasibility of nerve stimulations by a TENG was firstly validated by Zhang et al., in 2014 [13]. The TENG device of a folding structure (

(A1)) was connected with a three-dimensional (3D) microneedle electrode array (MEA) (

(A2)), which was implanted into real frog tissue to stimulate the sciatic nerve. When the external force was applied to the TENG device, the instantaneous output voltage induced the loop current among the microneedle tips via the sciatic nerve. Therefore, the sciatic nerve was stimulated by the loop current and actuated the leg muscle of the frog, as shown in

(A3).

Triboelectric nanogenerator (TENG)-based nerve stimulations. (

) The stimulation of a frog’s sciatic nerve using a TENG device connected with a microneedle electrode array (MEA): (

). The 3D structure of the high performance TENG device; (

) The microneedle electrode array used for nerve stimulations; (

) Photos that illustrate the real-time response of frog’s leg by the stimulation of the microneedle electrode array driven by the TENG device. Reproduced with permission from [13]. Copyright 2014 Elsevier; (

) The vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) system using a TENG device attach to the stomach [14]: (

) Operation principle of the self-powered VNS system and the implanted TENG device; (

) Schematics of the working principle of TENG device under different stomach motion stages). (

) The stimulation of a rat’s sciatic nerve using a stack-layer TENG device connected with a sling electrode: (

) The stack-layer TENG device and its voltage output; (

) The sling neural electrode used for nerve stimulations; (

) The photo that illustrates the sciatic nerve stimulation and recorded EMG signals. Reproduced with permission from [16]. Copyright 2017 Elsevier; (

) A selective stimulation of tibial nerve and common peroneal nerve using a multi-pixel TENG device: (

) The multi-pixel TENG device; (

) The plantar flexion induced by the stimulation of the tibial nerve; (

) The ankle dorflexion induced by the stimulation of the peroneal nerve. Reproduced with permission from [15]. Copyright 2018 Elsevier.

3. The Perspective for a TENG-Based Self-Powered Neuroprosthetic System

Although Yao et al. demonstrated a self-powered VNS system on a rat for a weight control application [14], this system could hardly meet the requirement for most neural modulation applications such as deep brain stimulation (DBS), vagus nerve stimulation (VNS), and functional electrical stimulation (FES) in humans. This is due to the fact that the current pulse frequency of TENG devices attached to the stomach and heart cannot be higher than 2 Hz, but the frequency of the current pulses required for a neuroprosthetic system is typically higher than 10 Hz. Therefore, the current demonstrated TENG-based neuroprosthetic system should be improved. Here, based on the state of the ongoing development of TENG-based nerve stimulation and relevant techniques, a perspective of the TENG-based self-powered neuroprosthetic system is proposed.

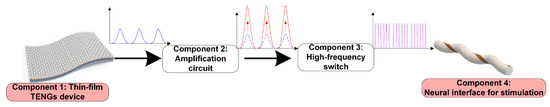

This TENG-based self-powered neuroprosthetic system consists of four major components, as shown in Figure 32. The first component is a thin film implantable TENG device, which requires a biocompatible package and can be driven by the heart, stomach, or hand tapping, if implanted beneath the skin. Since the frequency of the mechanical operation cannot fulfil the high-frequency current pulses required for neural modulation, a high-frequency switch is necessary to generate high-frequency current pulses (component 3 in Figure 32). The operation of this high-frequency switch can easily be achieved by a field-effect transistor (FET) or a relay, which is explained in detail in a subsequent section. However, when a single current pulse of low frequency is divided into a series of current pulses of high frequency, the amplitude of each current pulse decreases, and thus can be insufficient for nerve stimulations. Therefore, between components 1 and 3, an amplification circuit is required to amplify the output of the TENG device and ensure that each current pulse is high enough for nerve stimulations (component 2 in Figure 32). Then, the last component is the neural interface to enable the electrical nerve stimulation.

Figure 32. A perspective for the TENG-based self-powered neuroprosthetic system.

4. Summary

With proper device optimization, all kinds of nervous systems can be directly stimulated. The perspective of a further developed more sophisticated neuroprosthetic system is proposed, which includes a thin-film TENG device with a biocompatible package, an amplification circuit to enhance the output, and a self-powered high-frequency switch to generate high-frequency current pulses for nerve stimulations. The recent development and progress of each part are reviewed and evaluated. The scenario proposed in Figure 32 depicts the future of this TENG-based self-powered neuroprosthetic system, which is promising for the application of DBS, FES, and VNS.

References

- Hatsopoulos, N.G.; Donoghue, J.P. The science of neural interface systems. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2009, 32, 249–266.

- Perlmutter, J.S.; Mink, J.W. Deep brain stimulation. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2006, 29, 229–257.

- Payne, D.J.; Gwynn, M.N.; Holmes, D.J.; Pompliano, D.L. Drugs for bad bugs: Confronting the challenges of antibacterial discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007, 6, 29–40.

- Lee, S.; Peh, W.Y.X.; Wang, J.; Yang, F.; Ho, J.S.; Thakor, N.V.; Yen, S.-C.; Lee, C. Toward Bioelectronic Medicine-Neuromodulation of Small Peripheral Nerves Using Flexible Neural Clip. Adv. Sci. 2017, 4, 1700149.

- Xiang, Z.; Sheshadri, S.; Lee, S.; Wang, J.; Xue, N.; Thakor, N.V.; Yen, S.-C.; Lee, C. Mapping of Small Nerve Trunks and Branches Using Adaptive Flexible Electrodes. Adv. Sci. 2016, 3, 1500386.

- Xiang, Z.; Yen, S.-C.; Sheshadri, S.; Wang, J.; Lee, S.; Liu, Y.-H.; Liao, L.-D.; Thakor, N.V.; Lee, C. Progress of Flexible Electronics in Neural Interfacing—A Self-Adaptive Non-Invasive Neural Ribbon Electrode for Small Nerves Recording. Adv. Mater. 2015, 28, 4472–4479.

- Xiang, Z.; Liu, J.; Lee, C. A flexible three-dimensional electrode mesh: An enabling technology for wireless brain-computer interface prostheses. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2016, 2, 16012.

- Gibney, E. The inside story on wearable electronics. Nat. Int. Wkly. J. Sci. 2015, 528, 26–28.

- Zhang, Y.; Castro, D.C.; Han, Y.; Wu, Y.; Guo, H.; Weng, Z.; Xue, Y.; Ausra, J.; Wang, X.; Li, R.; et al. Battery-free, lightweight, injectable microsystem for in vivo wireless pharmacology and optogenetics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 21427–21437.

- Hinchet, R.; Kim, S. Wearable and Implantable Mechanical Energy Harvesters for Self-Powered Biomedical Systems. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 7742–7745.

- Dagdeviren, C.; Li, Z.; Wang, Z.L. Energy Harvesting from the Animal/Human Body for Self-Powered Electronics. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 19, 85–108.

- Jiang, D.; Shi, B.; Ouyang, H.; Fan, Y.; Wang, Z.L.; Li, Z. Emerging Implantable Energy Harvesters and Self-Powered Implantable Medical Electronics. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 6436–6448.

- Zhang, X.-S.; Han, M.-D.; Wang, R.; Meng, B.; Zhu, F.; Sun, X.-M.; Hu, W.; Wang, W.; Li, Z.-H.; Zhang, H. High-performance triboelectric nanogenerator with enhanced energy density based on single-step fluorocarbon plasma treatment. Nano Energy 2014, 4, 123–131.

- Yao, G.; Kang, L.; Li, J.; Long, Y.; Wei, H.; Ferreira, C.A.; Jeffery, J.J.; Lin, Y.; Cai, W.; Wang, X. Effective weight control via an implanted self-powered vagus nerve stimulation device. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 5349.

- Lee, S.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Shi, Q.; Yen, S.-C.; Thakor, N.V.; Lee, C. Battery-free neuromodulator for peripheral nerve direct stimulation. Nano Energy 2018, 50, 148–158.

- Lee, S.; Wang, H.; Shi, Q.; Dhakar, L.; Wang, J.; Thakor, N.V.; Yen, S.-C.; Lee, C. Development of battery-free neural interface and modulated control of tibialis anterior muscle via common peroneal nerve based on triboelectric nanogenerators (TENGs). Nano Energy 2017, 33, 1–11.

- Lee, S.; Wang, H.; Peh, W.Y.X.; He, T.; Yen, S.-C.; Thakor, N.V.; Lee, C.; Tianyiyi, H. Mechano-neuromodulation of autonomic pelvic nerve for underactive bladder: A triboelectric neurostimulator integrated with flexible neural clip interface. Nano Energy 2019, 60, 449–456.

- Wang, J.; Wang, H.; He, T.; He, B.; Thakor, N.V.; Lee, C. Investigation of Low-Current Direct Stimulation for Rehabilitation Treatment Related to Muscle Function Loss Using Self-Powered TENG System. Adv. Sci. 2019, 6, 1900149.

- Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Thakor, N.V.; Lee, C. Self-Powered Direct Muscle Stimulation Using a Triboelectric Nanogenerator (TENG) Integrated with a Flexible Multiple-Channel Intramuscular Electrode. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 3589–3599.

- Wang, H.; Wang, J.; He, T.; Li, Z.; Lee, C. Direct muscle stimulation using diode-amplified triboelectric nanogenerators (TENGs). Nano Energy 2019, 63, 103844.

- He, T.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Tian, X.; Wen, F.; Shi, Q.; Ho, J.S.; Lee, C. Self-Sustainable Wearable Textile Nano-Energy Nano-System (NENS) for Next-Generation Healthcare Applications. Adv. Sci. 2019, 6, 1901437.

- Shi, Q.; Dong, B.; He, T.; Sun, Z.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Lee, C. Progress in wearable electronics/photonics—Moving toward the era of artificial intelligence and internet of things. InfoMat 2020.

- Zhu, M.; He, T.; Lee, C. Technologies toward next generation human machine interfaces: From machine learning enhanced tactile sensing to neuromorphic sensory systems. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2020, 7, 031305.

- Hassani, F.A.; Shi, Q.; Wen, F.; He, T.; Haroun, A.; Yang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Lee, C. Smart Materials for Smart Healthcare—Moving from Sensors and Actuators to Self-sustained Nanoenergy Nanosystems. Smart Mater. Med. 2020, 1, 92–124.

- Wen, F.; He, T.; Liu, H.; Chen, H.-Y.; Zhang, T.; Lee, C. Advances in chemical sensing technology for enabling the next-generation self-sustainable integrated wearable system in the IoT era. Nano Energy 2020, 78, 105155.

- Chen, L.; Shi, Q.; Sun, Y.; Nguyen, T.; Lee, C.; Soh, S. Controlling Surface Charge Generated by Contact Electrification: Strategies and Applications. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1802405.

- Dhakar, L.; Gudla, S.; Shan, X.; Wang, Z.; Tay, F.E.H.; Heng, C.-H.; Lee, C. Large Scale Triboelectric Nanogenerator and Self-Powered Pressure Sensor Array Using Low Cost Roll-to-Roll UV Embossing. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 22253.

- Dhakar, L.; Pitchappa, P.; Tay, F.E.H.; Lee, C. An intelligent skin based self-powered finger motion sensor integrated with triboelectric nanogenerator. Nano Energy 2016, 19, 532–540.

- Wang, H.; Xiang, Z.; Giorgia, P.; Mu, X.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.L.; Lee, C. Triboelectric liquid volume sensor for self-powered lab-on-chip applications. Nano Energy 2016, 23, 80–88.

- Wang, H.; Pastorin, G.; Lee, C. Toward Self-Powered Wearable Adhesive Skin Patch with Bendable Microneedle Array for Transdermal Drug Delivery. Adv. Sci. 2016, 3, 1500441.

- Shi, Q.; Wang, H.; Wang, T.; Lee, C. Self-powered liquid triboelectric microfluidic sensor for pressure sensing and finger motion monitoring applications. Nano Energy 2016, 30, 450–459.

- Gupta, R.K.; Shi, Q.; Dhakar, L.; Wang, T.; Heng, C.H.; Lee, C. Broadband Energy Harvester Using Non-linear Polymer Spring and Electromagnetic/Triboelectric Hybrid Mechanism. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41396.

- Shi, Q.; Wu, H.; Wang, H.; Wu, H.; Lee, C. Self-Powered Gyroscope Ball Using a Triboelectric Mechanism. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017, 7, 1701300.

- Shi, Q.; Wang, H.; Wu, H.; Lee, C. Self-powered triboelectric nanogenerator buoy ball for applications ranging from environment monitoring to water wave energy farm. Nano Energy 2017, 40, 203–213.

- Wang, H.; Wu, H.; Hasan, D.; He, T.; Shi, Q.; Lee, C. Self-Powered Dual-Mode Amenity Sensor Based on the Water–Air Triboelectric Nanogenerator. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 10337–10346.

- Wu, H.; Shi, Q.; Wang, F.; Thean, A.V.-Y.; Lee, C. Self-Powered Cursor Using a Triboelectric Mechanism. Small Methods 2018, 2, 1800078.

- Chen, T.; Shi, Q.; Yang, Z.; Liu, J.; Liu, H.; Sun, L.; Lee, C. A Self-Powered Six-Axis Tactile Sensor by Using Triboelectric Mechanism. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 503.

- Chen, T.; Shi, Q.; Li, K.; Yang, Z.; Liu, H.; Sun, L.; Dziuban, J.A.; Lee, C. Investigation of Position Sensing and Energy Harvesting of a Flexible Triboelectric Touch Pad. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 613.

- Chen, T.; Shi, Q.; Zhu, M.; He, T.; Sun, L.; Yang, L.; Lee, C. Triboelectric Self-Powered Wearable Flexible Patch as 3D Motion Control Interface for Robotic Manipulator. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 11561–11571.

- Koh, K.H.; Shi, Q.; Cao, S.; Ma, D.; Tan, H.Y.; Guo, Z.; Lee, C. A self-powered 3D activity inertial sensor using hybrid sensing mechanisms. Nano Energy 2019, 56, 651–661.

- He, T.; Shi, Q.; Wang, H.; Wen, F.; Chen, T.; Ouyang, J.; Lee, C. Beyond energy harvesting-multi-functional triboelectric nanosensors on a textile. Nano Energy 2019, 57, 338–352.

- Shi, Q.; He, T.; Lee, C. More than energy harvesting–Combining triboelectric nanogenerator and flexible electronics technology for enabling novel micro-/nano-systems. Nano Energy 2019, 57, 851–871.

- Sun, C.; Shi, Q.; Hasan, D.; Yazici, M.S.; Zhu, M.; Ma, Y.; Dong, B.; Liu, Y.; Lee, C. Self-powered multifunctional monitoring system using hybrid integrated triboelectric nanogenerators and piezoelectric microsensors. Nano Energy 2019, 58, 612–623.

- Shi, Q.; Qiu, C.; He, T.; Wu, F.; Zhu, M.; Dziuban, J.A.; Walczak, R.; Yuce, M.R.; Lee, C. Triboelectric single-electrode-output control interface using patterned grid electrode. Nano Energy 2019, 60, 545–556.

- Wang, Z.; Yang, S.; Miao, S.; Shi, Q.; He, T.; Lee, C. A Motion-Balanced Sensor Based on the Triboelectricity of Nano-iron Suspension and Flexible Polymer. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 690.

- Shi, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, T.; Lee, C. Minimalist and multi-functional human machine interface (HMI) using a flexible wearable triboelectric patch. Nano Energy 2019, 62, 355–366.

- Nayak, S.; Li, Y.; Tay, W.; Zamburg, E.; Singh, D.; Lee, C.; Koh, S.J.A.; Chia, P.; Thean, A.V.-Y. Liquid-metal-elastomer foam for moldable multi-functional triboelectric energy harvesting and force sensing. Nano Energy 2019, 64, 103912.

- Shi, Q.; Lee, C. Self-Powered Bio-Inspired Spider-Net-Coding Interface Using Single-Electrode Triboelectric Nanogenerator. Adv. Sci. 2019, 6, 1900617.

- Qiu, C.; Wu, F.; Shi, Q.; Lee, C.; Yuce, M.R. Sensors and Control Interface Methods Based on Triboelectric Nanogenerator in IoT Applications. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 92745–92757.

- Liu, D.; Yin, X.; Guo, H.; Zhou, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, C.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.L. A constant current triboelectric nanogenerator arising from electrostatic breakdown. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaav6437.

- Qiu, C.; Wu, F.; Lee, C.; Yuce, M.R. Self-powered control interface based on Gray code with hybrid triboelectric and photovoltaics energy harvesting for IoT smart home and access control applications. Nano Energy 2020, 70, 104456.

- Zhao, K.; Gu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Yang, F.; Zhao, L.; Zheng, M.; Cheng, G.; Du, Z. The self-powered CO2 gas sensor based on gas discharge induced by triboelectric nanogenerator. Nano Energy 2018, 53, 898–905.

- Kim, H.; Yim, E.-C.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, S.-J.; Park, J.Y.; Oh, I.-K. Bacterial Nano-Cellulose Triboelectric Nanogenerator. Nano Energy 2017, 33, 130–137.

- Lee, B.-Y.; Kim, D.H.; Park, J.; Park, K.-I.; Lee, K.J.; Jeong, C.K. Modulation of surface physics and chemistry in triboelectric energy harvesting technologies. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2019, 20, 758–773.

- Lim, K.-W.; Peddigari, M.; Park, C.H.; Lee, H.Y.; Min, Y.; Kim, J.-W.; Ahn, C.-W.; Choi, J.-J.; Hahn, B.-D.; Choi, J.-H.; et al. A high output magneto-mechano-triboelectric generator enabled by accelerated water-soluble nano-bullets for powering a wireless indoor positioning system. Energy Environ. Sci. 2019, 12, 666–674.