You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Sirius Huang and Version 1 by Tao Qin.

Perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.) is an important turfgrass and gramineous forage widely grown in temperate regions around the world. However, its perennial nature leads to the inevitable exposure of perennial ryegrass to various environmental stresses on a seasonal basis and from year to year. Like other plants, perennial ryegrass has evolved sophisticated mechanisms to make appropriate adjustments in growth and development in order to adapt to the stress environment at both the physiological and molecular levels. A thorough understanding of the mechanisms of perennial ryegrass response to abiotic stresses is crucial for obtaining superior stress-tolerant varieties through molecular breeding.

- Lolium perenne L.

- drought

- salt

- stress resistance gene

- molecular mechanism

1. Introduction

Perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.), native to Europe, Asia, and Northern Africa, is a cool-season perennial grass cultivated around the world with a breeding history of more than 100 years [11,12][1][2]. Due to its outstanding forage quality, long growing season, high yield, grazing tolerance, and high palatability, perennial ryegrass is the most widely cultivated perennial gramineous forage in temperate regions [13,14,15][3][4][5]. Due to its prominent lawn quality, perennial ryegrass is also used as turf grass on golf courses, sports fields, and parks [16,17][6][7]. For example, it accounts for 50% of the total used land and 70% of agricultural land in the UK [18][8]. As a consequence of its wide distribution and perennial characteristics, perennial ryegrass is exposed to, and has to respond to, a variety of abiotic stresses. These abiotic stresses are sometimes seasonal, but increasingly unpredictable due to climate change [19][9]. Therefore, abiotic stresses such as drought, high salinity, and extreme temperatures are major restrictive factors in perennial ryegrass growth and management [12,17,20][2][7][10]. Breeding stress-resistance cultivars is considered as an important measure to mitigate the effects of abiotic stress on perennial ryegrass [17,19][7][9]. However, as perennial ryegrass is a self-incompatible species [21[11][12],22], and that plant tolerance to abiotic stresses is a complex quantitative trait involving multiple genes and complex mechanisms, breeding varieties in perennial ryegrass by conventional breeding strategies (e.g., hybrids, induced mutations, and somaclonal variation) is time-consuming and often yields unpredictable results [23,24,25][13][14][15]. The draft genome sequence of perennial ryegrass was reported in 2015 [26][16], and there is more genetic and genomic information available than other major perennial herb species [21,27][11][17]. Thus, it is widely accepted that genetic engineering is a perfect alternative for the improvement in stress resistance [25][15]. The knowledge of stress resistance genes and molecular mechanisms of perennial ryegrass is of great significance for cultivating new varieties with strong stress resistance.

2. Drought Stress

Drought is a major constraint to the growth and development of perennial ryegrass with typical symptoms including leaf senescence and desiccation, slow shoot and root growth, and even death [25,30][15][18]. Knowledge about the adaptation mechanisms of perennial ryegrass to drought stress is important for sustainable agriculture. The ability of plants to maintain growth and survival when subjected to drought stress is broadly defined as drought resistance [31][19]. Drought resistance is a quantitative characteristic that is determined by many genes and biochemical processes [1,32][20][21]. The identification and characterization of genes associated with drought resistance are critical in clarifying the mechanisms of perennial ryegrass adaptation to drought stress. However, the research on drought stress-related genes of perennial ryegrass is very limited, and molecular mechanisms in response to the drought environment are mostly unknown. Some drought response genes of perennial ryegrass found in limited studies are as follows. Through transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses, Foito et al. identified 38 and 15 genes with significantly increased expression under water stress in the leaves and roots, respectively. The transcripts homologous to known dehydration responsive element binding (DREB) transcription factors and aquaporins were identified [33][22]. The dehydration-responsive element (DRE), a 9-bp conserved sequence TACCGACAT, is essential for regulating the expression of dehydration response genes [34][23]. DREB transcription factors specifically combine with DRE cis-acting elements and have a vital function on conducting stress responses such as drought and salt. Transgenic ryegrass overexpressing Arabidopsis DREB1B shows stronger drought resistance [35][24]. These data suggest that DREB transcription factors may be key regulators of perennial ryegrass response to drought stress. By analyzing the transcriptome of perennial ryegrass leaves and roots under drought stress, Amiard et al. found that myoinositol inositol 1-phosphate synthase (INPS) and galactinol synthase (GOLS) regulate the content of loliose and raffinose under drought stress [36][25]. In addition to the transcriptional analysis, the results of the genome-wide association study (GWAS) of the drought tolerance traits in 192 perennial ryegrass cultivars distributed in 43 countries suggested that Lolium perenne Late Embryogenesis Abundant3 (LpLEA3) and Superoxide Dismutase (LpFeSOD) are important for maintaining the leaf water content under drought stress [23][13].

Determining the role of drought-responsive genes in the adaptation of perennial ryegrass to drought stress by genetic transformation is very important in clarifying the drought resistance mechanism, as has been carried out in Arabidopsis and other crops [37][26]. It has been proven that Lolium perenne pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthase (LpP5CS) plays a vital role in the response to diverse stresses and is potentially a candidate gene for stress-related molecular breeding in perennial ryegrass [38][27]. LpP5CS includes all conserved functional sites and regions of P5CS [38,39][27][28]. The overexpression of LpP5CS in tobacco plants, especially the mutation form LpP5CSF128A without the feedback inhibition of proline, enhances the tolerance to drought stress [38][27]. The ubiquitin-like (Ubl) post-translational modifiers contain a subfamily designated ‘Homology to Ub1′ (HUB1), which is also known as Ubl5 [40][29]. Although HUB1 proteins are cognate with ubiquitins in structure, their amino acid resemblance to ubiquitins is only about 35% [40][29]. It is worth noting that transgenic perennial ryegrass overexpressing LpHUB1 exhibits an improved drought tolerance phenotype with a higher relative water content and growth rate under drought stress. As an ubiquitin-like modifier, LpHUB1 may regulate the protein interaction, activity, and cellular location of existing proteins in response to a stress environment [25][15].

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are indispensable in the post-transcriptional regulation of target genes. Studying variations of miRNAs in ryegrass is crucial for comprehending the stress response mechanisms [41][30]. miRNA408 (miR408), a conserved miRNA, is known to take part in multiple kinds of stress responses and has a central function in plant survival under a stress environment [42,43][31][32]. The overexpression of miR408 in Arabidopsis results in an increased tolerance to salinity, low temperature, and oxidative stress, but decreased tolerance to drought and osmotic stress [44][33]. A recent study revealed that transgenic perennial ryegrass with heterologous expression of the rice (Oryza sativa L.) miR408 gene showed improved drought tolerance, which may be due to changes in the leaf morphology and increase in the antioxidant capacity [45][34]. These data demonstrate that miR408 may have different functions in Arabidopsis and in gramineous plants and is able to act as a potential target for genetic manipulation to improve the drought tolerance of perennial ryegrass.

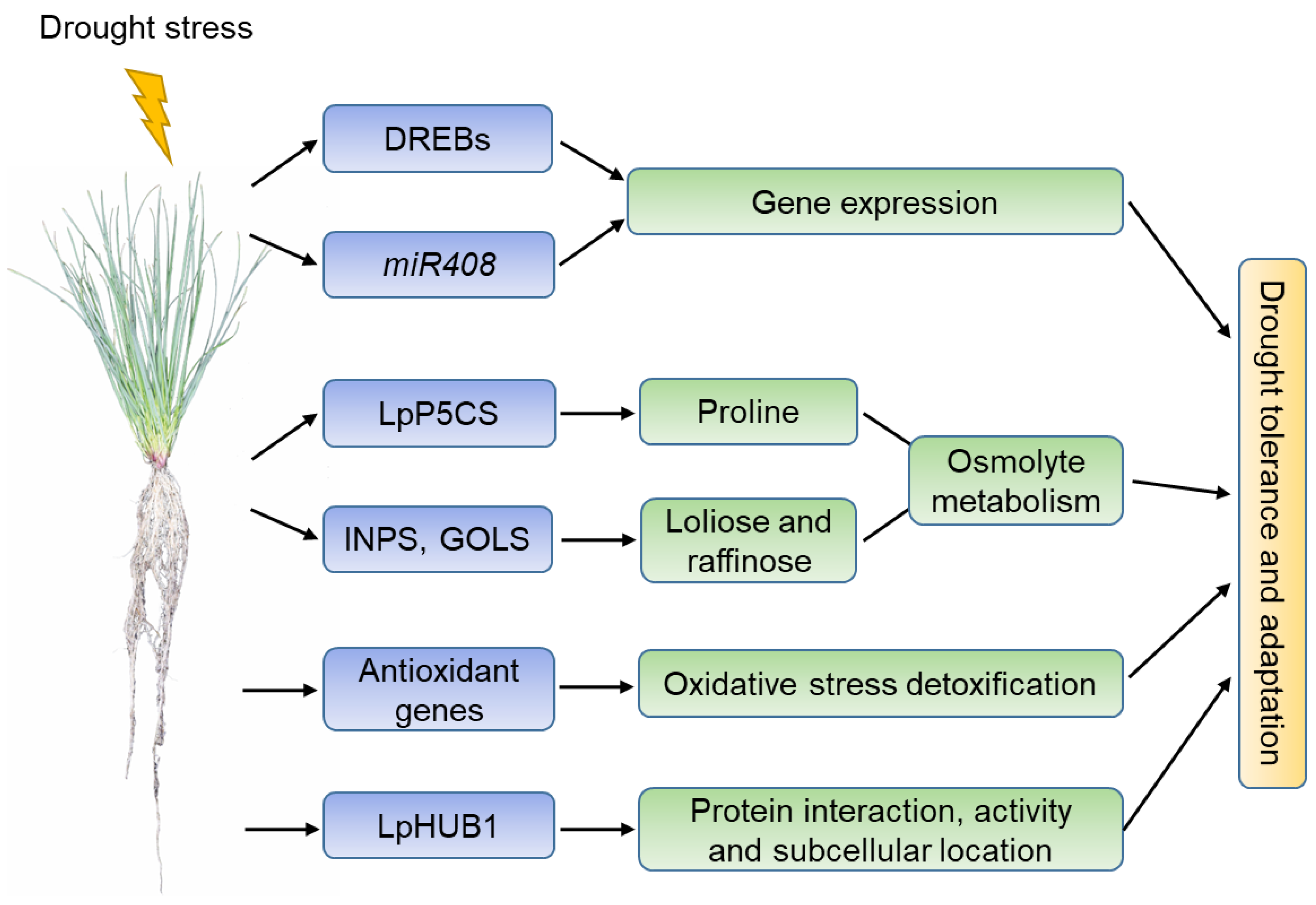

Although more drought-responsive genes in perennial ryegrass should be identified, the current studies have shown that the drought stress signaling and mechanisms of perennial ryegrass are as follow: (1) Under drought conditions, DREB transcription factors regulate the expression of stress-responsive genes together with miRNAs such as miR408; (2) the expression of proline synthase LpP5CS and loliose- and raffinose-metabolism enzymes INPS and GOLS are differentially regulated under drought conditions, leading to changes in osmolyte metabolism and tolerance to drought stress; (3) the expression of LpSOD and other antioxidant enzymes such as POD, CAT, and APX maintains the homeostasis of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (i.e., H2O2, OH•, 1O2, and O2−) under drought conditions, and results in the adaptation of perennial ryegrass to drought stress; (4) LpHUB1, an ubiquitin-like modifier, regulates the protein interaction, activity, and cellular location of existing proteins under stress environments and promotes the adaptation of perennial ryegrass to drought stress (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A schematic model of the perennial ryegrass response to drought stress. Abbreviations: DREB, dehydration responsive element binding; miR408, miRNA408; P5CS, pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthase; INPS, myoinositol inositol 1-phosphate synthase; GOLS, galactinol synthase; SOD, superoxide dismutase; HUB1, homology to Ub1.

3. Salt Stress

Salt stress causes harm to perennial ryegrass through ionic stress, osmotic stress, and secondary stresses including the accumulation of toxic compounds and the disruption of nutrient balance. A reduction in the shoot and root dry weight is commonly observed in cool-season gramineous grass under salinity stress [46,47][35][36]. Although a complete understanding of the gene function of perennial ryegrass is yet to be achieved, identifying the genes that play central roles in salt response and tolerance will provide new insights into the molecular mechanisms. According to previous studies, the salt-overly-sensitive (SOS) signal transduction pathway is a pivotal mechanism of salt tolerance in Arabidopsis. In this pathway, the calcium-binding protein, SOS3, is activated by the elevated free Ca2+ in cytosolic when suffering under high salinity [48][37]. SOS3 interacts with a serine/threonine protein kinase, SOS2, to form a SOS2/SOS3 complex, which leads to the activation of SOS1 [49,50,51][38][39][40]. The results of the suppression of subtractive hybridization and RT-PCR analysis in perennial ryegrass showed that approximately 22% of salt-responsive genes were related to general metabolism, 16% to interrelated protein metabolism, 12% related to signaling/transcription, and 2–4% associated with detoxification and energy transfer [52][41]. By RT-PCR, Liu et al. demonstrated that the expression levels of LpSOS1 increased in the roots of perennial ryegrass but decreased in the stem under salt stress. Moreover, the expressions of NHX1, TIP1, and PIP were also associated with salinity tolerance in perennial ryegrass [53][42]. The salt tolerance of transgenic perennial ryegrass was significantly improved by the transformation of the rice vacuolar Na+/H+ antiporter OsNHX1 [54][43]. Furthermore, Li et al. isolated two salt-induced P5CS genes (P5CS1 and P5CS2) from perennial ryegrass by using rapid-amplification of cDNA ends PCR (RACE-PCR). The accumulation of proline, which is significantly induced after salt treatment, is in line with the expression levels of those two P5CS genes under high salinity treatment [20][10], suggesting that both P5CS genes may be involved in the salt stress tolerance of perennial ryegrass.

A high salinity environment induces excessive ROS such as H2O2, OH•, and O2−, leading to organelle and tissue injury. In order to suppress the damage caused by ROS, plants usually produce more antioxidant enzymes to maintain ROS homeostasis [55][44]. Beyond that, Ca2+ and H2O2 are vital secondary messengers in plant signaling networks, triggering different physiological and molecular responses to various environmental stresses [56,57,58][45][46][47]. By treatments of perennial ryegrass with NaCl, exogenous Ca2+, and H2O2, and determination of the physiological indexes and the contents of Ca2+, H2O2, OH•, and O2−, Hu et al. proved that Ca2+ and H2O2 signaling were integrated to enhance the adaptation to stress conditions in perennial ryegrass. Ca2+ signaling maintains ROS homeostasis in stressed grasses by increasing the responses of antioxidant genes, proteins, and enzymes. H2O2 signaling also induces antioxidant genes but attenuates the signaling of Ca2+ in the root of perennial ryegrass [59][48]. Consistently, the results of RT-PCR suggest that the expressions of CAT, POD, APX, GPX, and GR are upregulated in perennial ryegrass under salt stress, suggesting that these antioxidant enzymes play an important role in eliminating ROS [55][44]. Collectively, the H2O2 and Ca2+ signaling of salinity response supplies a strategy for the adaptation of perennial ryegrass to salt stress. Additionally, other micromolecule metabolites are profoundly involved in salinity tolerance [60][49]. A study on the stress memory by the RT-PCR analysis of stress memory genes and GC–MS analysis of the metabolite profiles demonstrated that the metabolites in perennial ryegrass such as sugar and sugar alcohol regulated by trainable genes Brown Plant Hopper Susceptibility Protein (PBSP) and Sucrose Synthase (SUCS) played positive roles in the physiological changes induced by stress memory. Moreover, pre-exposure to multiple low NaCl concentrations improved the salinity response of perennial ryegrass to a subsequent worse salinity environment [61][50]. The application of exogenous cytokinin 6-benzylaminopurine (BAP) upregulates the gene expression of Lolium perenne High-affinity Potassium Transporter (LpHKT) and LpMYB and alleviates salt-induced cell damage and leaf senescence in perennial ryegrass [47][36]. Acetic acid is a natural endogenous substance to resist salt stress in perennial ryegrass. The results of transcriptome sequencing and acetic acid content determination under salt stress showed that the content of endogenous acetic acid gradually increased, along with the elevated expression of the key biosynthetic gene LpPDC1, under high salinity conditions [62][51].

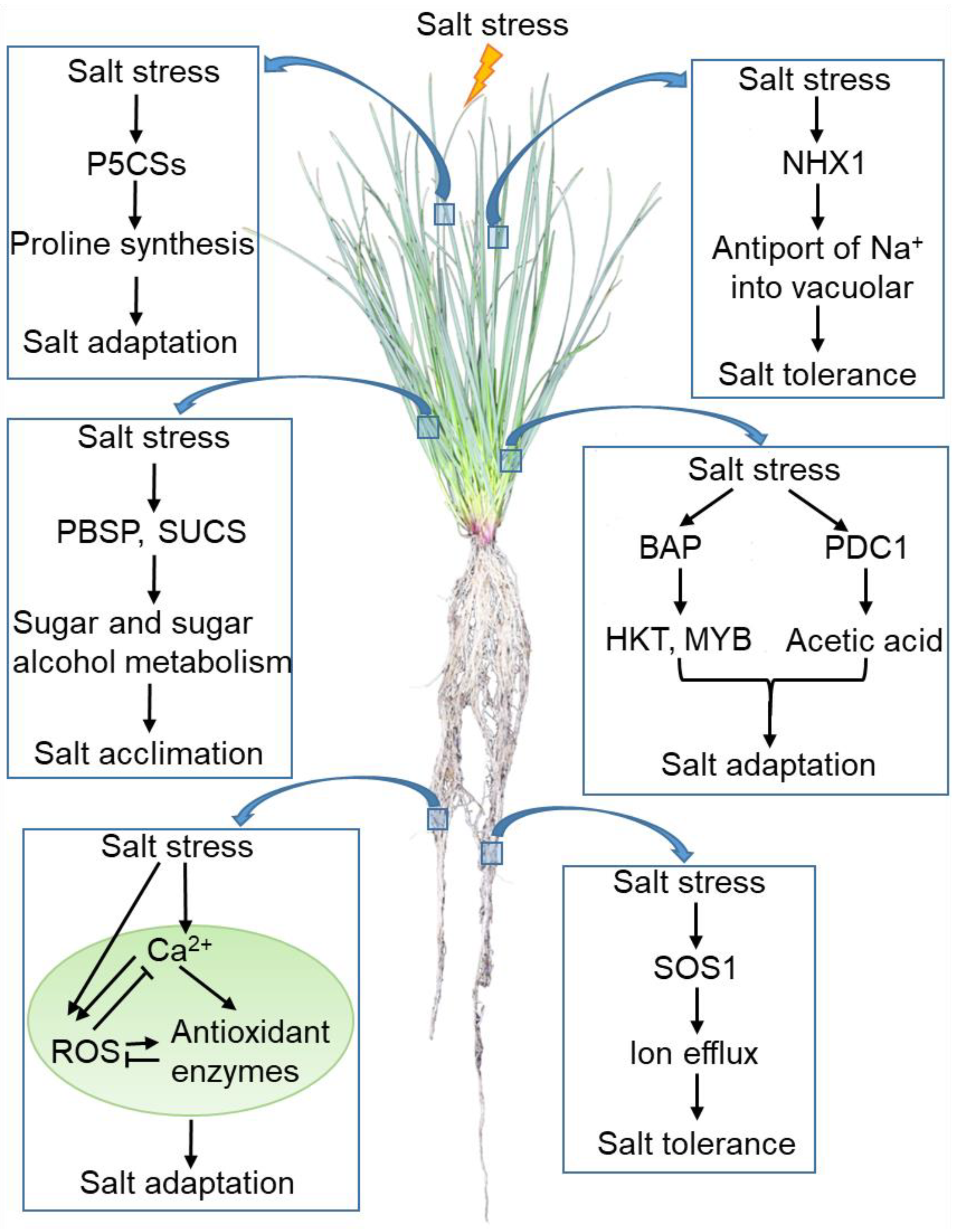

For the purpose of improving the tolerance of perennial ryegrass to salt stress, it is of great significance in understanding the response strategies and signal transduction processes. Although it remains unknown how Na+ is sensed in cellular systems and what the complete salt stress signaling network in perennial ryegrass is, the current studies show that perennial ryegrass may adopt the following strategies to adapt to high salinity stress. (1) Under salt stress, SOS1 and NHX1 are activated and mediate the efflux of ion or antiport of Na+ into the vacuolar, leading to the adaptation of ryegrass to salt stress. (2) Salt stress activates the expression of P5CS genes or PBSP and SUCS. These genes alleviate the damage of osmotic stress by regulating the synthesis of osmolytes under salt stress. PBSP and SUCS also regulate the salt acclimation by mediating the metabolism of sugar and sugar alcohol. (3) Salt stress induces the increase in cytosolic Ca2+ and ROS concentrations, which triggers the downstream signaling networks to enhance the adaptation of perennial ryegrass to salt stress. It is worth noting that excessive ROS is harmful. Both Ca2+ and H2O2 increase the expression and activity of antioxidant enzymes (e.g., CAT, POD, APX, GPX, and GR) to maintain ROS homeostasis in stressed grasses. (4) Some endogenous bioorganic micromolecules such as BAP and acetic acid also serve functions in the perennial ryegrass response to salt tolerance (Figure 2).

Figure 2. A schematic model of the perennial ryegrass response to salt stress. The arrow represents positive regulation, whereas the line ending with a bar represents negative regulation. Abbreviations: SOS1, Salt Overly Sensitive 1; NHX1, Na+/H+ antiporter 1; P5CS, Pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthase; PBSP, Brown Plant Hopper Susceptibility Protein; SUCS, Sucrose Synthase; ROS, reactive oxygen species; BAP, 6-benzylaminopurine; HKT, High-affinity Potassium Transporter; MYB, MYB transcription factor.

References

- Sun, T.X.; Shao, K.; Huang, Y.; Lei, Y.Y.; Tan, L.Y.; Chan, Z.L. Natural variation analysis of perennial ryegrass in response to abiotic stress highlights LpHSFC1b as a positive regulator of heat stress. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2020, 179, 104192.

- Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Jiang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, Z.; Xu, B.; Huang, B. Natural variation of physiological traits, molecular markers, and chlorophyll catabolic genes associated with heat tolerance in perennial ryegrass accessions. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 520.

- Fu, Z.; Song, J.; Zhao, J.; Jameson, P.E. Identification and expression of genes associated with the abscission layer controlling seed shattering in Lolium perenne. AoB Plants 2019, 11, ply076.

- Xie, L.; Teng, K.; Tan, P.; Chao, Y.; Li, Y.; Guo, W.; Han, L. PacBio single-molecule long-read sequencing shed new light on the transcripts and splice isoforms of the perennial ryegrass. Mol. Genet. Genom. 2020, 295, 475–489.

- Yu, X.; Pijut, P.M.; Byrne, S.; Asp, T.; Bai, G.; Jiang, Y. Candidate gene association mapping for winter survival and spring regrowth in perennial ryegrass. Plant Sci. 2015, 235, 37–45.

- Kemesyte, V.; Statkeviciute, G.; Brazauskas, G. Perennial ryegrass yield performance under abiotic stress. Crop Sci. 2017, 57, 1935–1940.

- Liu, S.; Jiang, Y. Identification of differentially expressed genes under drought stress in perennial ryegrass. Physiol. Plant 2010, 139, 375–387.

- King, J.; Thorogood, D.; Edwards, K.J.; Armstead, I.P.; Roberts, L.; Skot, K.; Hanley, Z.; King, I.P. Development of a genomic microsatellite library in perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne) and its use in trait mapping. Ann. Bot. 2008, 101, 845–853.

- Fradera-Sola, A.; Thomas, A.; Gasior, D.; Harper, J.; Hegarty, M.; Armstead, I.; Fernandez-Fuentes, N. Differential gene expression and gene ontologies associated with increasing water-stress in leaf and root transcriptomes of perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne). PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220518.

- Li, H.; Guo, H.; Zhang, X.; Fu, J.; Rognli, O.A. Expression profiles of Pr5CS1 and Pr5CS2 genes and proline accumulation under salinity stress in perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.). Plant Breed. 2014, 133, 243–249.

- Kubik, C.; Sawkins, M.; Meyer, W.A.; Gaut, B.S. Genetic diversity in seven perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.) cultivars based on SSR markers. Crop Sci. 2001, 41, 1565–1572.

- Xing, Y.; Frei, U.; Schejbel, B.; Asp, T.; Lubberstedt, T. Nucleotide diversity and linkage disequilibrium in 11 expressed resistance candidate genes in Lolium perenne. BMC Plant Biol. 2007, 7, 43.

- Yu, X.; Bai, G.; Liu, S.; Luo, N.; Wang, Y.; Richmond, D.S.; Pijut, P.M.; Jackson, S.A.; Yu, J.; Jiang, Y. Association of candidate genes with drought tolerance traits in diverse perennial ryegrass accessions. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 1537–1551.

- Sathish, P.; Withana, N.; Biswas, M.; Bryant, C.; Templeton, K.; Al-Wahb, M.; Smith-Espinoza, C.; Roche, J.R.; Elborough, K.M.; Phillips, J.R. Transcriptome analysis reveals season-specific rbcS gene expression profiles in diploid perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.). Plant Biotechnol. J. 2007, 5, 146–161.

- Patel, M.; Milla-Lewis, S.; Zhang, W.; Templeton, K.; Reynolds, W.C.; Richardson, K.; Biswas, M.; Zuleta, M.C.; Dewey, R.E.; Qu, R.; et al. Overexpression of ubiquitin-like LpHUB1 gene confers drought tolerance in perennial ryegrass. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2015, 13, 689–699.

- Byrne, S.L.; Nagy, I.; Pfeifer, M.; Armstead, I.; Swain, S.; Studer, B.; Mayer, K.; Campbell, J.D.; Czaban, A.; Hentrup, S.; et al. A synteny-based draft genome sequence of the forage grass Lolium perenne. Plant J. 2015, 84, 816–826.

- Jensen, L.B.; Muylle, H.; Arens, P.; Andersen, C.H.; Holm, P.B.; Ghesquiere, M.; Julier, B.; Lubberstedt, T.; Nielsen, K.K.; De Riek, J.; et al. Development and mapping of a public reference set of SSR markers in Lolium perenne L. Mol. Ecol. Notes 2005, 5, 951–957.

- Fry, J.; Huang, B. Applied Turfgrass Science and Physiology; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; p. 130.

- Harb, A.; Krishnan, A.; Ambavaram, M.M.; Pereira, A. Molecular and physiological analysis of drought stress in Arabidopsis reveals early responses leading to acclimation in plant growth. Plant Physiol. 2010, 154, 1254–1271.

- Gong, Z.; Xiong, L.; Shi, H.; Yang, S.; Herrera-Estrella, L.R.; Xu, G.; Chao, D.Y.; Li, J.; Wang, P.Y.; Qin, F.; et al. Plant abiotic stress response and nutrient use efficiency. Sci. China Life Sci. 2020, 63, 635–674.

- Fang, Y.; Xiong, L. General mechanisms of drought response and their application in drought resistance improvement in plants. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2015, 72, 673–689.

- Foito, A.; Byrne, S.L.; Shepherd, T.; Stewart, D.; Barth, S. Transcriptional and metabolic profiles of Lolium perenne L. genotypes in response to a PEG-induced water stress. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2009, 7, 719–732.

- Liu, Q.; Kasuga, M.; Sakuma, Y.; Abe, H.; Miura, S.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; Shinozaki, K. Two transcription factors, DREB1 and DREB2, with an EREBP/AP2 DNA binding domain separate two cellular signal transduction pathways in drought- and low-temperature-responsive gene expression, respectively, in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 1998, 10, 1391–1406.

- Yang, F.; Liang, R.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X.; Sun, Z. Perennial Ryegrass transformed with the adversity-resistant transcription factor DREB1B gene. Acta Bot. Boreal -Occident Sin. 2006, 26, 1309–1315.

- Amiard, V.; Morvan-Bertrand, A.; Billard, J.P.; Huault, C.; Keller, F.; Prud’homme, M.P. Fructans, but not the sucrosyl-galactosides, raffinose and loliose, are affected by drought stress in perennial ryegrass. Plant Physiol. 2003, 132, 2218–2229.

- Bhatnagar-Mathur, P.; Vadez, V.; Sharma, K.K. Transgenic approaches for abiotic stress tolerance in plants: Retrospect and prospects. Plant Cell Rep. 2008, 27, 411–424.

- Cao, L.; Han, L.; Zhang, H.L.; Xin, H.B.; Imtiaz, M.; Yi, M.F.; Sun, Z.Y.; Ju, G.S.; Qian, Y.Q.; Liu, J.X. Isolation and characterization of pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase gene from perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.). Acta Physiol. Plant 2015, 37, 62.

- Szabados, L.; Savoure, A. Proline: A multifunctional amino acid. Trends Plant Sci. 2010, 15, 89–97.

- Downes, B.; Vierstra, R.D. Post-translational regulation in plants employing a diverse set of polypeptide tags. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2005, 33, 393–399.

- Fan, J.B.; Zhang, W.H.; Amombo, E.; Hu, L.X.; Kjorven, J.O.; Chen, L. Mechanisms of environmental stress tolerance in turfgrass. Agronomy 2020, 10, 522.

- Abdel-Ghany, S.E.; Pilon, M. MicroRNA-mediated systemic down-regulation of copper protein expression in response to low copper availability in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 15932–15945.

- Sun, M.Z.; Yang, J.K.; Cai, X.X.; Shen, Y.; Cui, N.; Zhu, Y.M.; Jia, B.W.; Sun, X.L. The opposite roles of OsmiR408 in cold and drought stress responses in Oryza sativa. Mol. Breed. 2018, 38, 120.

- Garcia, M.E.; Lynch, T.; Peeters, J.; Snowden, C.; Finkelstein, R. A small plant-specific protein family of ABI five binding proteins (AFPs) regulates stress response in germinating Arabidopsis seeds and seedlings. Plant Mol. Biol. 2008, 67, 643–658.

- Hang, N.; Shi, T.; Liu, Y.; Ye, W.; Taier, G.; Sun, Y.; Wang, K.; Zhang, W. Overexpression of OsmicroRNA408 enhances drought tolerance in perennial ryegrass. Physiol. Plant 2021, 172, 733–747.

- Cen, H.; Ye, W.; Liu, Y.; Li, D.; Wang, K.; Zhang, W. Overexpression of a chimeric gene, OsDST-SRDX, improved salt tolerance of perennial ryegrass. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 27320.

- Ma, X.; Zhang, J.; Huang, B. Cytokinin-mitigation of salt-induced leaf senescence in perennial ryegrass involving the activation of antioxidant systems and ionic balance. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2016, 125, 1–11.

- Liu, J.; Zhu, J.K. A calcium sensor homolog required for plant salt tolerance. Science 1998, 280, 1943–1945.

- Halfter, U.; Ishitani, M.; Zhu, J.K. The Arabidopsis SOS2 protein kinase physically interacts with and is activated by the calcium-binding protein SOS3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 3735–3740.

- Ishitani, M.; Liu, J.; Halfter, U.; Kim, C.S.; Shi, W.; Zhu, J.K. SOS3 function in plant salt tolerance requires N-myristoylation and calcium binding. Plant Cell 2000, 12, 1667–1678.

- Zhu, J.K. Salt and drought stress signal transduction in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2002, 53, 247–273.

- Li, H.; Hu, T.; Fu, J. Identification of genes associated with adaptation to NaCl toxicity in perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2012, 79, 153–162.

- Liu, M.X.; Song, X.; Jiang, Y.W. Growth, ionic response, and gene expression of shoots and roots of perennial ryegrass under salinity stress. Acta Physiol. Plant 2018, 40, 112.

- Wu, Y.Y.; Chen, Q.J.; Chen, M.; Chen, J.; Wang, X.C. Salt-tolerant transgenic perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.) obtained by Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation of the vacuolar Na+/H+ antiporter gene. Plant Sci. 2005, 169, 65–73.

- Hu, T.; Li, H.Y.; Zhang, X.Z.; Luo, H.J.; Fu, J.M. Toxic effect of NaCl on ion metabolism, antioxidative enzymes and gene expression of perennial ryegrass. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2011, 74, 2050–2056.

- Ma, Y.; Dai, X.; Xu, Y.; Luo, W.; Zheng, X.; Zeng, D.; Pan, Y.; Lin, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, D.; et al. COLD1 confers chilling tolerance in rice. Cell 2015, 160, 1209–1221.

- Sun, J.; Wang, M.J.; Ding, M.Q.; Deng, S.R.; Liu, M.Q.; Lu, C.F.; Zhou, X.Y.; Shen, X.; Zheng, X.J.; Zhang, Z.K.; et al. H2O2 and cytosolic Ca2+ signals triggered by the PM H+-coupled transport system mediate K+/Na+ homeostasis in NaCl-stressed Populus euphratica cells. Plant Cell Environ. 2010, 33, 943–958.

- Zhu, X.; Feng, Y.; Liang, G.; Liu, N.; Zhu, J.K. Aequorin-based luminescence imaging reveals stimulus- and tissue-specific Ca2+ dynamics in Arabidopsis plants. Mol. Plant 2013, 6, 444–455.

- Hu, T.; Chen, K.; Hu, L.; Amombo, E.; Fu, J. H2O2 and Ca2+-based signaling and associated ion accumulation, antioxidant systems and secondary metabolism orchestrate the response to NaCl stress in perennial ryegrass. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36396.

- Krasensky, J.; Jonak, C. Drought, salt, and temperature stress-induced metabolic rearrangements and regulatory networks. J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, 1593–1608.

- Hu, T.; Jin, Y.; Li, H.; Amombo, E.; Fu, J. Stress memory induced transcriptional and metabolic changes of perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne) in response to salt stress. Physiol. Plant 2016, 156, 54–69.

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Xing, J.; Li, H.; Miao, J.; Xu, B. Acetic acid mitigated salt stress by alleviating ionic and oxidative damages and regulating hormone metabolism in perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.). Grass Res. 2021, 1, 1–10.

More