1. Introduction

1. Schizophrenia

1.1 History of curcumin

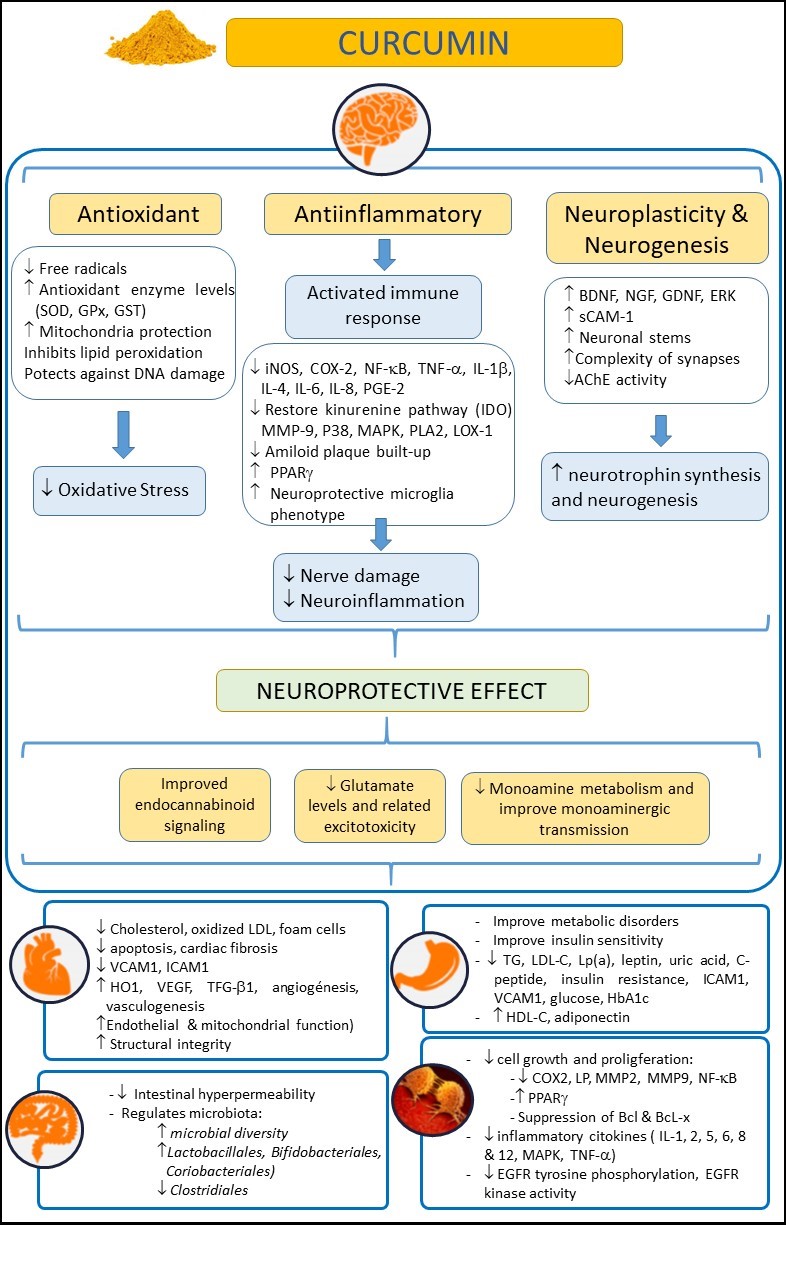

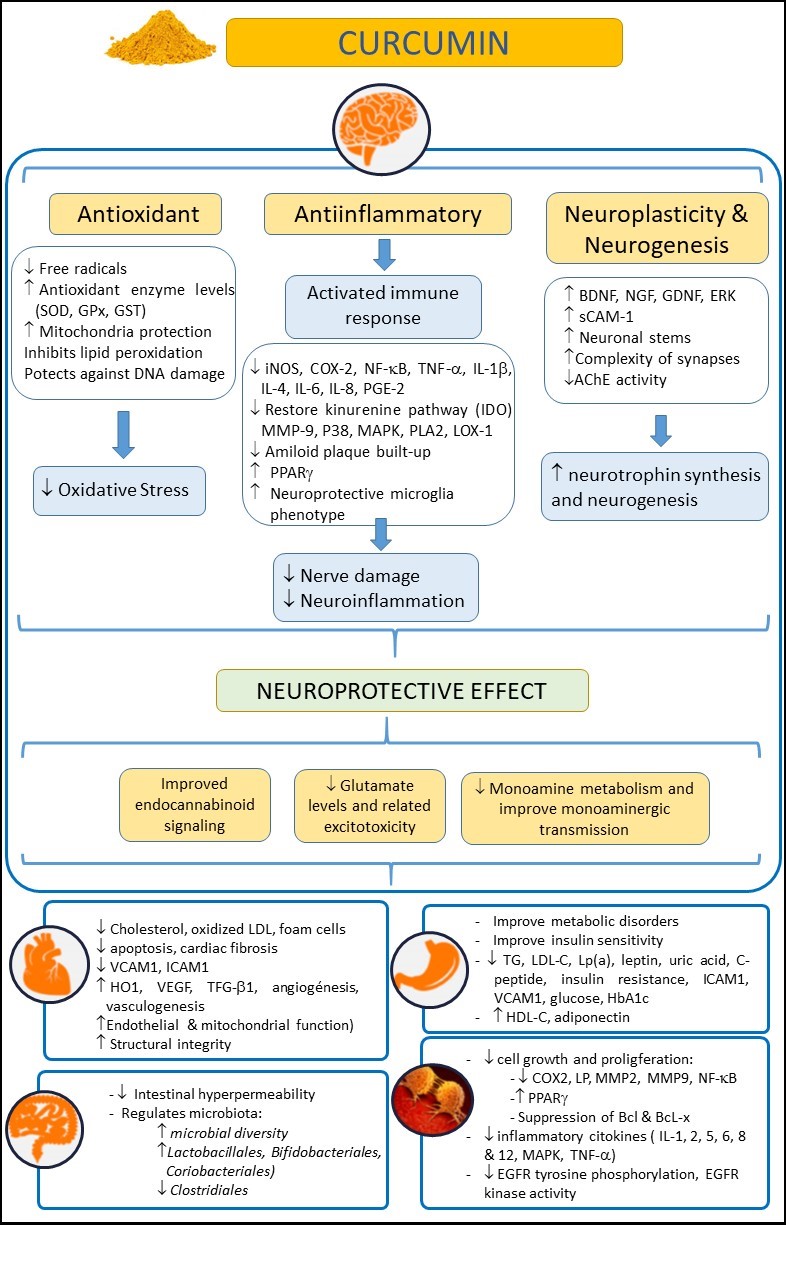

Turmeric (Curcuma longa) is an herbaceous plant widely used in Asia as a dye, culinary spice, and as a traditional natural therapeutic compound [1]. The rhizome of this plant, also called turmeric, is enriched with yellow dyes, the curcuminoids [2]. Within this family of compounds, curcumin is considered one of the most relevant. Curcumin, the active compound of turmeric, is a polyphenol that has also been largely used as a remedy for different pathologies in Asia for several decades due to its healthy and biopharmacological properties, and its lack of adverse effects, even at high doses. Moreover, curcumin has been reported to have anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, neuroprotective, and even anti-aging and antineoplasic properties [3][4][5][6][7] (Figure 1). Curcumin may exert its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant (anti-IOS) effects by influencing the synthesis of some IOS regulators, such as heme-oxygenase-1 (HO1), glutathione (GSH), catalase (CAT), and superoxide dismutase (SOD) [8]. These properties cause curcumin to have an impact on those diseases in which IOS regulation does not work correctly and are related to the disease appearance. Thus, curcumin may exert a beneficial effect on the immune system, reducing B lymphocyte proliferation by inhibiting B lymphocyte stimulator (BLYS).

Figure 1. Summary of potential beneficial effects of curcumin on health, in neurological, cardiovascular, intestinal, metabolic, and oncological disorders. Abbreviations: AChE: acetylcholinesterase; Bcl: B-cell lymphoma; BDNF: brain-derived neurotrophic factor; COX-2: cyclooxygenase 2; EGFR: epidermal growth factor receptor; ERK: extracellular-regulated kinase; 9 GDNF: glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor; GPx: glutathione peroxidase; GSH: glutathione; GST: glutathione S-transferase; HbA1c: glycosylated hemoglobin A1c; HDL-C: high density lipoprotein cholesterol; HO-1: heme-oxygenase-1; ICAM-1: intercellular adhesion molecule-1; IL: interleukin; iNOS: inducible nitric oxide synthase; IL-10: Interleukin-10; LDL-C: low density lipoprotein cholesterol; LOX-1: lectin-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor-1; Lp(a): lipoprotein(a); LP: lipoxygenase; MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase; MMP-9: matrix metalloproteinase 9; NF-κB: nuclear factor kappa-B; NGF: Nerve growth factor; PLA2: phospholipase A2; P38: p38 MAKP; PGE-2: prostaglandin E2; PPARγ: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma; sCAM-1: soluble cell adhesion molecule 1; TG: triglycerides; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor-α; TGF-β1: transforming growth factor; SOD: superoxide dismutase; VCAM-1: vascular cell adhesion molecule-1; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor.

Curcumin can also reduce the neutrophil recruitment to areas affected by inflammation [9], and can also increase the phagocytic activity of macrophages [10]. Furthermore, curcumin has proven to be an effective modulator of the endocrine system, enhancing the uptake or regulating some hormones, such as insulin [11]. All these properties have boosted the interest of researchers in this compound in recent decades. Thus, several preclinical studies and clinical trials have been conducted [12] with the aim of elucidating whether or not curcumin was effective for many different diseases, such as skin [13], cancer, or neurological pathologies [5].

1.2 Applications of curcumin

Recently, curcumin has also been used in different psychiatric disorders due to the likely involvement of IOS processes in their onset and evolution. In this sense, the above-described role of curcumin as an anti-IOS drug made this compound a good candidate to halt or palliate the course of these diseases. This is especially important, as current therapeutic strategies for many psychiatric disorders have a relatively high failure rate. Thus, the search for new approaches to help address this problem is ongoing.

So far, several clinical trials and studies with animal models, which will detail in depth in the following sections, which were reported the efficacy of curcumin in some psychiatric disorders, such as depression, schizophrenia, or autism. However, some studies have showed no positive effects of curcumin in neurological diseases. The main and most recommended route of administration of curcumin is oral and, despite considerable high absorption through lipid membranes caused by its lipophilic nature, curcumin has a low bioavailability after being metabolized, accumulating in the spleen, liver, and intestine, with a low uptake in the rest of the organs [8][14][15]. The low absorption by the small intestine and the high metabolism in the liver weaken its oral bioavailability [16], making it necessary to use high oral doses of curcumin to reach other target organs such as the brain [16]. Moreover, its apparent ineffectiveness in interacting specifically with a single pharmacological target has prompted the classification of curcumin as a pan assay interference compound (PAINS) and an invalid metabolic panacea (IMPS) [17][18]. However, despite the poor pharmacokinetics of this compound, the existence of positive results in several studies raises the question of how curcumin could cause a beneficial effect at the brain level despite being barely able to reach this organ. A recent hypothesis explains that curcumin could be acting on the gut microbiota [19] since the intestine and liver are primary sites of metabolism for curcumin [16], reducing intestinal inflammation and, hence, functioning as a neuroprotective agent due to the likely involvement of neuroinflammation in many psychiatric disorders in which alterations of the gut-brain axis play an important role [2][20]. Furthermore, in order to address the low bioavailability of the curcumin, new formulations of this compound are being synthetized to improve its pharmacokinetics and achieve stable curcumin that can reach the brain in a higher concentration. Some of them are based on conjugating curcumin with lipids or co-treating it with piperine, a bio-enhancer that improves the absorption of curcumin [8][21]. A recent emerging and promising strategy to improve its bioavailability in the brain combines curcumin with drug delivery carriers such as liposomes, exosomes, magnetic particles or ultrasound bubbles [22]. Moreover, some of these exosomes have shown an anti-inflammatory capacity [23], which could enhance the anti-inflammatory effect of curcumin in the brain and other organs of interest. Of note, oral and intra-nasal administration of nanoparticles are also being explored, which could increase drug absorption in the brain, representing a great advantage in brain disorders [24][25].

2. Current Status of Curcumin in Neurpopsychiatric Disorders

2.1 Schizophrenia

Current therapies for schizophrenia mostly focus on treatment with antipsychotics, the prolonged use of which is prone to cause severe extrapyramidal side effects, such as parkinsonism or tardive dyskinesia

[26][27]. In addition, long-term administration of typical antipsychotics decreases antioxidant enzyme levels, thus perhaps participating in the exacerbation of oxidative events

[27][28]. Therefore, the search for new approaches is of great importance. In this regard, the likely involvement of oxidative stress and inflammation in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia has supported the use of curcumin in various preclinical and clinical studies.

On the preclinical side,

we only found two studies

were found. In the first one, curcumin-loaded nanoparticles (30 mg/kg, i.p.) were administered to ketamine-treated rats, achieving a reduction in metalloproteases (MMP), adenosine triphosphate (ATP), and mitochondrial enzyme complex II activity in cerebellar mitochondria, along with a reduction in the over-increased locomotor activities in the side-to-side rocking and neck arcing tests

[28][29]. In the second one, published in 2021, the administration of curcumin (30 mg/kg, i.p.) to ketamine-treated mice induced a reduction in oxidative stress biomarkers in the brain, and a reduction in anxiety and depression-like behaviors

[29][30].

On the clinical arena, five studies and trials have been conducted. The first one is an OLS (NCT01875822) in which 17 schizophrenic patients received 1 or 4 g of curcumin or placebo for 16 weeks. However, to

theour knowledge, there are no published results to date. In 2017, the first randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study reporting the effects of curcumin on brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a neurotrophin involved in neuroprotection, neuroregeneration and cell survival among other functions, and cognition in 36 patients with schizophrenia and inpatients was published

[30][31]. Patients receiving curcumin (360 mg/day for 8 weeks) showed an increased in BDNF levels relative to baseline and compared to placebo. However, the study failed to find any effect on cognition or other clinical symptoms. In contrast, the three most recent studies showed more promising results as an add-on to antipsychotics in the treatment of negative symptoms (NCT02298985, NCT02476708) or both positive and negative symptoms

[31][32]. The first study, an 8-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel, fixed-dose pilot clinical trial in 12 patients with schizophrenia, showed that 300 mg of curcumin add-on to conventional medication significantly improved working memory and reduced interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels

[32][33]. The second study, also a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, add-on clinical trial reported an improvement in negative symptoms in 20 patients receiving curcumin (3 g/day, for 24 weeks) compared to 18 patients receiving placebo

[33][34]. Finally, in the third randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial, curcumin (160 mg/day, for 16 weeks) plus usual antipsychotic medication was administered to 28 patients with chronic schizophrenia (28 additional patients received a placebo). Curcumin-treated patients showed an improvement on the negative and positive subscales, the general psychopathology subscale, total Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), Clinical Global Impressions-Severity (CGI-S), and Clinical Global Impressions (CGI-I) scores in comparison with the control group

[31][32].

Therefore, the schizophrenia picture shows an unbalanced proportion of preclinical and clinical studies, biased towards the clinical ones. In all cases, curcumin was well-tolerated and, overall, an improvement of clinical symptoms was observed, especially in negative symptomatology. However, the heterogeneity of doses and curcumin formulations used precludes drawing more robust conclusions.

2.2 Depression

2. Depression

Pathophysiology and aetiology of major depression disorder (MDD) are heterogeneous, and traditional antidepressant treatments have some limitations in terms of efficacy, symptom improvement, and side effects. Although the pathological mechanisms are not fully understood, oxidative stress and inflammation seem to play an important role in the pathogenesis of depression, probably through increased inflammatory factors in the central nervous system. In this regard, curcumin has been used and demonstrated to be an effective adjuvant treatment for MDD in several studies.

On the preclinical side, we found a total of 57 studies were found, 19 of which were performed in mice and 38 in rats. The dose of curcumin ranged from 1 to 300 mg/Kg. The duration of treatment varied from a single intake to a 5-week treatment with curcumin. Regarding the route of administration, 36 used oral administration (23 in the drinking water or food and 13 by gavage), 19 used intraperitoneal administration, and two of them reported no information on the route of administration. In addition, several models of MDD were used, most of them (21) based on a stress-induced model, such as Chronic Unpredictable Mild Stress (CUMS), Single Prolonged Stress (SPS), Chronic Unpredictable Stress (CUS), or Chronic Mild Stress (CMS), while eight of them were induced by surgery (olfactory bulbectomy, ovarectomy, chronic constriction injury or middle cerebral artery occlusion), nine were induced by the administration of reserpine or corticosterone (CORT), and the remaining 19 were induced by other models of MDD.

The antidepressant efficacy of curcumin in modulating depressive behavior in different animal models has been shown in a large number of behavioral studies. Most of the studies reported improved performance in the forced swimming test

[34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47][35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48], increased locomotor activity in the open field test

[48][49][50][51][52][53][54][55][56][57][58][59][60][61][62][63][49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64], decreased anxiety in the elevated plus maze test

[56][58][63][64][65][57,59,64,65,66], improved anhedonia in the sucrose preference test

[50][51][53][55][57][61][66][67][68][69][70][71][72][73][74][75][51,52,54,56,58,62,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76], improved short and long-term memory in the passive avoidance test

[48][49][54][49,50,55] and water maze test

[53][59][76][54,60,77], reduced escape response in the shuttle-box test

[77][78], attenuated the effort-related abnormalities in a choice procedure test

[78][79], and reduced stress in the tail suspension test

[49][63][65][68][79][80][81][82][83][84][85][86][87][50,64,66,69,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88]. Only one study found no improvements in anxiety, as measured by the open field and elevated plus maze tests, nor in “depressive-like” states, as measured by the forced swimming test

[88][89]. Another study found no improvements in anhedonia, as measured by the sucrose preference test

[85][86].

The administration of curcumin has been shown to regulate serotonin (5-HT), dopamine (DA), and noradrenaline (NA) levels. Twenty studies reported an increment of 5-HT levels in the hippocampus, striatum or frontal cortex, which may be due to the interaction found between curcumin and 5-HT/cAMP/PKA/CREB/BDNF-signaling pathway or 5-HT

1A/1B and 5-HT

2C receptors

[34][39][79][82][84][89][35,40,80,83,85,90]. Besides, fifteen studies reported an increased level of DA

[37][40][41][43][44][45][47][48][54][71][76][80][86][90][38,41,42,44,45,46,48,49,55,72,77,81,87,91]. NA was also incremented in five studies

[45][48][54][62][85][46,49,55,63,86]. In addition, curcumin has been claimed to present beneficial effects on reducing inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6)

[59][62][68][69][70][75][76][90][60,63,69,70,71,76,77,91], reducing the NF-κB-iNOS-COX-2-TNF-α inflammatory signaling pathway

[38][50][51][39,51,52], and modulating the levels of antioxidant markers, such as monoamine oxidase (MAO), malondialdehyde (MDA), CAT, or SOD

[42][55][56][61][64][65][81][83][87][43,56,57,62,65,66,82,84,88]. Furthermore, the BDNF is incremented by curcumin treatment

[35][38][46][50][53][57][65][66][76][77][89][36,39,47,51,54,58,66,67,77,78,90]. Other effects of curcumin have been described in different animal models of depression, such as an interaction with glutamate N-Methyl-D-Aspartate (NMDA) receptors

[36][37], an inhibition of Ca

+2 channels

[73][74], an increased level of corticosterol and cortisone in plasma

[63][64], or an altered lipid metabolism

[74][75], or an upregulation of the insulin receptor IRS-1 and protein kinase-B (PKB) in the liver

[72][73]. In contrast, only one study reported no effects of curcumin, regarding its interaction with the benzodiazepine site on gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor

[88][89].

Only two neuroimaging studies have evaluated the effect of curcumin on brain morphometry and glucose metabolism in an animal model of depression, showing improvements such as a reduction in hippocampal atrophy

[49][50] and an activation of the metabolism of the amygdala in a positron emission tomography (PET) imaging study after curcumin treatment

[52][53].

In the clinical setting, one

open-label clinical studies (OLS

) and eight clinical trials were performed. In 2013, two trials were conducted, one in India (NCT01022632)

[91][92] and one in Israel (NCT01750359)

[92][93]. In the first one, a randomized, active controlled, parallel group trial, curcumin (1000 mg/day) or fluoxetine (20 mg/day) were administered to patients with MDD for 6 weeks (17 patients on fluoxetine alone, 16 patients on curcumin, and 18 patients on fluoxetine/curcumin), which showed no biological effects on depressive symptoms, as measured by the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS). In the second study, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, pilot clinical trial, curcumin (1000 mg/day, for 8 weeks) was administered to 19 patients (27 patients on placebo), showing no improvement in the MDD symptoms measured by the HDRS and the Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating (MADRS) scales.

In contrast, the remaining trials conducted from 2014 until now showed better results. In 2014, two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials were conducted in Australia in 25 patients with MDD receiving curcumin (1000 mg/day, for 8 weeks) and 25–27 patients receiving placebo

[93][94][94,95]. Both studies showed an improvement in MDD symptomatology (IDS-SR30 total score), and the second one also found an increase in some depression-related biomarkers, such as urinary Thromboxane B2 (TBX-B2) and substance-P (SUB-P), and plasma endothelin-1 (ET-1) and leptin levels. Thus, higher levels of these biomarkers were associated with greater reductions in IDS-S30 total scores.

In 2015, one OLS in Iran

[95][96] and a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in China were conducted

[96][97]. In the first study, curcumin (1000 mg/day, for 6 weeks) was administered to 61 patients with MDD (50 patients on placebo), showing a decrease in anxiety levels as measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and reductions in MDD symptomatology as measured by the Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II) scale

[95][96]. Of note, piperine (10 mg/day) was used to increase the bioavailability of curcumin. In the second trial, curcumin (1000 mg/day, for 6 weeks) was administered to 50 patients with MDD (50 patients on placebo), showing an improvement in the HDRS and MADRS scales

[96][97].

In 2017, another randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial was conducted in Australia

[97][98]. The effects of two different doses of curcumin (500 mg/day or 1000 mg/day, for 12 weeks) was evaluated in 28 and 33 patients with MDD, respectively. Both doses induced improvements in symptomatology and anxiety measured by IDS-SR30 and State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) scales, with no difference between the doses used. In 2018, a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial was performed in 30 patients with MDD treated with an increasing dose of curcumin (500 mg/day to 1500 mg/day with increments of 250 mg/week, for 12 weeks) and 31 on placebo

[98][99]. This escalating medication dosage induced an improvement in the severity of depression on the MADRS scale. Despite this behavioral improvement, no significant effects were found in blood chemistry and electrocardiogram measurements.

Finally, a randomized, placebo-controlled trial is currently in the recruiting phase (NCT04744545 2021). The study estimates to recruit 60 patients with MDD, with curcumin (1500 mg/day) as an adjuvant treatment for MDD.

2.3 Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

3. Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

Although the etiology of this disorder is largely unknown, oxidative stress and inflammation have been hypothesized to be key factors in its occurrence, especially through an exacerbated increase in pro-inflammatory metalloproteases. In this sense, the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant potential of curcumin could be effective in alleviating this disorder.

So far, no clinical trials have been conducted in patients with ASD. On the preclinical field, only four studies have been performed in animal models, two in rats and two in mice. The first study used a model based on the intracerebroventricular injection of propanoic acid (PPA) in Sprague-Dawley rats. After the PPA injection, curcumin was orally administered for 4 weeks at different doses (50/100/200 mg/kg). The treatment restored many behavioral defects in PPA rats, such as social interaction, anxiety, depression, and repetitive behaviors. In addition, curcumin reduced the levels of MMP-9 and Thiobarbituric Acid Reactive Substances (TBARs), increased the activity of GSH, CAT, and SOD, and restored normal function of mitochondrial enzyme complex 1

[99][100]. In 2017, another study, based on prenatal valproic acid (VPA) exposure to fetal Wistar rats, proposed early postnatal administration of curcumin (first seven days after birth). This approach was reported to restore oxidative stress deficits and the abnormal body and brain weight values

[100][101]. Two subsequent studies were performed in the BTBRT

+ltpr3

tf/J (BTBRT) mouse model. The first one, in which curcumin (20 mg/kg) was administered from PND 6 to 8, reported enhanced neural stem cell proliferation, along with increased sociability and improved short-term memory

[101][102]. The second study evaluated three different doses of curcumin (25/50/100 mg/kg), showing restoration of different oxidative stress markers in the hippocampus and cerebellum, along with a dose-dependent increase in sociability in curcumin-treated mice

[102][103].

Taken together, these results suggest that curcumin could be effective in preventing some autistic behavioral and biochemical traits, but the lack of clinical trials do not allow for drawing solid conclusions.

2.4. Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

4. Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

The etiology of OCD is not fully understood either, but it has been hypothesized that it is a result of the existence of a deficit of monoamines in specific brain regions such as the orbitofrontal cortex and the anterior cingulate gyrus. In this regard, the potential of curcumin as an inhibitor of MAO-A and MAO-B, both of which are involved in monoamines degradation

[96][97], led researchers to test its efficacy as an adjuvant treatment in this disorder.

Only two preclinical studies have been conducted to date. The first, carried out in 2010 by Jithendra and Murthy, evaluated the potential of orally administered curcumin (5 or 10 mg/kg) as a therapeutic approach to reduce obsessive-compulsive signs in the quinpirole-induced OCD rat model. Following treatment with both doses, a reduction in brain DA levels, together with an increase in serotonin levels, was observed in curcumin-treated pathological rats. In addition, an improvement in obsessive-compulsive symptoms together with a protective effect on the water maze memory task at both doses was reported

[96][97]. The second study was recently conducted, in 2021, by Mishra et al.

TIn this work, they intraperitoneally administered ethanolic extract of curcumin (10, 15, 25, or 40 mg/kg) to Swiss albino mice that had poor performance in the marble-burying behavior (MBB) and motor activity (MA) tests. The treatment at the dose of 40 mg/kg resulted in improved performance in the MBB test, but not in the MA

[97][98].

From a clinical point of view, no OLS or trials have been conducted to date. However, a case report was announced in 2018

,. in whichIn this case, a 3-year-old child with a diagnosis of OCD and tics was treated with a combination of N-acetylcysteine (dose increase from 600 to 1800 mg/day) and curcumin (90 mg/day). After 7 days, a complete remission of tics and OCD symptoms was observed. Finally, after 3 weeks, symptoms remitted completely, together with a drastic reduction in Children’s Yale–Brown Obsessive Compulsive (CY-BOCS) and Yale Global Tic Severity (YGTSS) total scores

[98][99].

Taken together, these data do not shed enough light to conclude whether curcumin is an effective compound for the treatment of OCD, especially in the case report, in which the observed positive effect could also be attributed to the administration of NAC.

3. Pros and Cons of Curcumin in Neuropsychiatric Disorders

Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and neuroprotective properties of curcumin, along with many multi-target beneficial effects, such as the modulation of monoamine synthesis, have exponentially promoted the investigation of its properties during this last decade. 296 articles containing research on curcumin were published in the PubMed database in 2005. In 2010, this number increased to 714 and, in 2020, to 2130. The field of psychiatry has not been immune to this boost. The likely involvement of oxidative stress, inflammation, and monoamine deficits in the pathophysiology of many psychiatric disorders, together with the poor response to current therapies in a significant proportion of these patients, have pushed researchers to investigate for new therapeutic compounds that could improve current treatments. Herein, the focuses are on the effects and efficacy of curcumin and its derivatives in four psychiatric disorders: schizophrenia, depression, autism, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). A total of 65 pre-clinical studies and 14 clinical trials were reported. Most of these studies were conducted in depression, approximately 88 % were preclinical studies and 64 % were clinical studies. In all disorders, curcumin was well tolerated, with no harmful side effects. This was not surprising, as curcumin has been used for the last centuries as an additive spice in East Asian cuisine. Moreover, curcumin was shown to be beneficial in palliating or reversing symptoms associated with psychiatry in all the studies analyzed and completed, with the exception of one preclinical and two clinical studies in depression, which reported no improvement [89][92].

As mentioned above, the percentage of studies on depression, as compared to autism and OCD, is highly unbalanced. This fact (no clinical trial on the effect of curcumin on either autism or OCD has been conducted so far) prevents from drawing solid conclusions on the possible effectiveness of curcumin in these disorders. This large bias towards studies on depression could be explained by a likely predisposition of patients with depression to use new therapies compared to psychotic or autistic patients. Nevertheless, it was believed that the efforts directed to the synthesis of new formulations of this compound, together with an improvement of its pharmacokinetic properties, will increase the interest in curcumin and decrease the reluctance to use it in more psychiatric disorders, such as OCD or autism.

In the case of schizophrenia, the reported outcomes showed a beneficial effect of curcumin in both preclinical and clinical studies. In clinical trials, curcumin proved to be effective in alleviating both positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia when administered together with regular antipsychotic medication. The clinical relevance of these results could be of great importance, due to the adverse events that can be caused by the extensive and chronic use of antipsychotics. Besides, its excessive use can lead to a paradoxical increase in oxidative stress and inflammation. In addition, some widely used antipsychotics, such as clozapine, are able to activate hepatic sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBPs) and enhance downstream lipogenesis, leading to an increase in lipid peroxides and brain phospholipase A2 (PLA2), which can lead to cell death [103]. In this sense, curcumin could exert its beneficial effect in schizophrenia through an inhibition of PLA2 enzyme [104]. Nevertheless, the heterogeneity of the protocols used in these studies, in terms of curcumin doses and stage of the disorder, makes it difficult to make comparisons between trials and draw a solid conclusion.

In depression, it was found the vast majority of studies, in both preclinical and clinical domains showed some beneficial effect of curcumin in reducing symptoms associated with depression. In addition to the recognized role of curcumin as an anti-inflammatory and antioxidant agent, positive improvement of depressive deficits could be exerted through modulation of the indolamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) enzyme, involved in the kynurenine pathways and, thus, in the inhibition of serotonin synthesis. Curcumin treatment was shown to be able to counteract the action of this enzyme [76][105]. Therefore, the overall effect of curcumin in this disorder seems to be mainly positive.

Even though the results here are overwhelmingly positive, there is a significant amount of literature warning about this compound, especially concerned about its poor pharmacokinetics and chemical instability, and its non-specific multi-target effects [17][18]. Although the results presented pointed in a different direction, it is considered relevant to mention, at least, these discordant voices which claim that curcumin is an unstable compound with barely therapeutic efficacy.

Finally, even though a thorough review is provided here, there are several limitations. First and foremost, the great heterogeneity of methodologies used in all the studies has hindered the possibility to make comparisons between studies. This has been especially relevant in the case of the different formulations of curcumin and the doses used. Secondly, the small number of trials and clinical studies carried out in some of the pathologies mentioned, together with the small number of participants in some of them, prevents from drawing solid conclusions. Thirdly, the small number of trials in some cases forced us to compare trials of the same disease but focused on different stages of the disease or on adjuvant treatments. Although it was conducted after an exhaustive search in well-known databases, there is always an intrinsic limitation derived from the non-systematic nature. One final remark derives from the well-known problem of publication bias towards positive results, which may prevent some negative-results studies from being reported in high impact journals, or even published at all.

4. Conclusion

Overall, curcumin, due to its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, has been shown to be effective in the vast majority of the studies presented. However, the lack of homogeneity of the protocols used and the scarce number of trials prevents from concluding whether curcumin is really a useful therapeutic tool in the psychiatric field.

Abbreviations

| AchE |

Acetylcholinesterase |

| ATP |

Adenosine triphosphate |

| ASD |

Autism spectrum disorders |

| Bcl |

B-cell lympho MAO |

| BDI-II |

Beck Depression Inventory II |

| BDNF |

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| BLYS |

B lymphocyte stimulator |

| Ca+2 |

Calcium |

| cAMP |

cyclic adenosine monophosphate |

| CAT |

Catalase |

| CGI-I |

Clinical global impressions-improvement |

| CGI-S |

Clinical global impressions-severity |

| CMS |

Chronic mild stress |

| COX-2 |

Cyclooxygenase-2 |

| CUMS |

Chronic unpredictable mild stress |

| CORT |

Corticosterone |

| CREB |

cAMP response element-binding protein |

| CUS |

Chronic unpredictable stress |

| CUR |

Curcumin |

| CY-BOCS |

Children’s Yale–Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale |

| DA |

Dopamine |

| DOPAC |

4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid |

| EGFR |

Epidermal growth factor receptor |

| ERK |

Extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| ET-1 |

Endothelin 1 |

| GABA |

Gamma-aminobutyric acid |

| GD |

Gestational day |

| GDNF |

Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor |

| GPx |

Glutathione peroxidase |

| GSH |

Glutathione |

| GST |

Glutathione S-transferase |

| HADS |

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

| HbA1c |

Glycosylated hemoglobin A1c |

| HDL-C |

High density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| HDRS |

Hamilton Depression Rating Scale |

| HO-1 |

Heme oxygenase-1 |

| ICAM-1 |

Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 |

| IDO |

Indolamine-2, 3-Dioxygenase |

| IDS-SR30 |

Inventory of depressive symptomatology |

| IFN-γ |

Interferon |

| IL-1β |

Interleukine-1β |

| IL-6 |

Interleukin-6 |

| IL-10 |

Interleukin-10; |

| IMPS |

Invalid metabolic panaceas |

| iNOS |

Inducible nitric oxide synthase |

| IOS |

Inflammation and oxidative stress |

| IRS-1 |

Insulin receptor substrate 1 |

| LDL-C |

Low density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| LOX-1 |

Lectin-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor |

| Lp(a) |

Lipoprotein(a) |

| LP |

Lipooxigenase |

| LPS |

Lipopolysaccharide |

| MADRS |

Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale |

| MA |

Motor activity test |

| MAO |

Monoamine oxidase |

| MAPK |

Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MBB |

Marble-burying behavior test |

| MCAO |

Middle cerebral artery occlusion |

| MDA |

Malondialdehyde |

| MDD |

Major depressive disorder |

| MEK |

Methyl ethyl ketone |

| MMP |

Mitochondrial membrane potential |

| MMP-9 |

Matrix metalloproteinase 9 |

| NA |

Noradrenaline |

| NF-κβ |

Nuclear factor κβ |

| NGF |

Nerve growth factor |

| NMDA |

N-Methyl-D-Aspartate |

| NQO-1 |

Quinine oxidoreductase-1 |

| OB |

Olfactory bulbectomy |

| OCD |

Obsessive compulsive disorder |

| OLS |

Open label clinical studies |

| OVX |

Ovarectomy/Ovarectomized |

| P38 |

P38 MAPK |

| PAINS |

Pan assay interference compound |

| PANSS |

Positive and negative syndrome scale |

| PGE-2 |

Prostaglandin E2 |

| PET |

Positron emission tomography |

| PKA |

Protein kinase A |

| PKB |

Protein kinase B |

| PLA2 |

Phospholipase A2 |

| PPA |

Propanoic acid |

| PPARγ |

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma |

| PSD-95 |

Postsynaptic density protein-95 |

| RCT |

Randomized clinical trial |

| sCAM-1 |

Soluble cell adhesion molecule 1 |

| SCZ |

Schizophrenia |

| SD |

Sprague-Dawley |

| SL327 |

ERK inhibitor |

| SNRIs |

Serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors |

| SOD |

Superoxide dismutase |

| SREBPs |

Hepatic sterol regulatory element-binding proteins |

| SPS |

Single prolonged stress |

| SSRIs |

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors |

| STAI |

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory |

| SUB-P |

Substance P |

| TBARs |

Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances |

| TBX-B2 |

Thromboxane B2 |

| TCAs |

Tricyclic antidepressants |

| TG |

Triglycerides |

| TGF-β1 |

Transforming growth factor |

| TN |

Trigeminal neuralgia |

| TNF-α |

Tumor necrosis factor |

| Tuj1 |

Neuron-specific class III β-tubulin |

| VCAM-1 |

Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 |

| VEGF |

Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| VPA |

Valproic acid |

| YGTSS |

Yale global tic severity scale |

| 5-HT |

Serotonin |