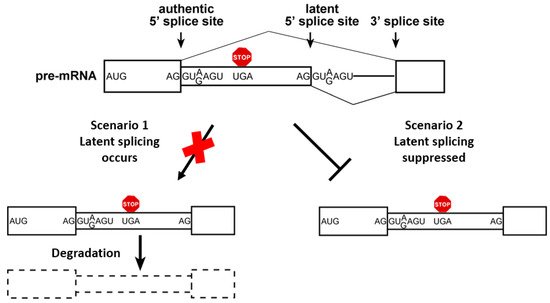

Splicing and alternative splicing (AS) must be tightly regulated, as they have profound effects on gene expression. Various cis-regulatory elements control the fidelity and efficiency of splicing. These include the 5′ and 3′ splice sites (SSs), splicing enhancers, splicing silencers, branch points, and polypyrimidine tracts. A quality control mechanism of splice site selection termed Suppression of Splicing (SOS), was proposed to protect cells from splicing at the numerous intronic unused, latent 5′ splice sites (LSSs) sequences, which are not used under normal growth condition. However, under stress and in cancer thousands of LSSs are activated in splicing resulting in the expression of thousands of aberrant nonsense mRNAs that may be toxic to cells.

- pre-mRNA splicing

- alternative splicing

- latent splicing

- aberrant splicing

- endogenous spliceosome

- breast cancer

- glioma

1. Alternative Splicing (AS) Is a Key Regulator of Human Gene Expression

2. The Endogenous Spliceosome

3. A Quality Control Mechanism of Splicing Regulation

4. Elements of the SOS Mechanism

4.1. SOS Requires Recognition of the Reading Frame in the Nucleus, Independent of Translation

4.2. A Role for Initiator-tRNA in SOS

4.3. A Novel Role for Nucleolin (NCL) in SOS

5. SOS is Abrogated under Stress and in Cancer

Previously, it has been shown that heat shock elicited latent splicing in the CAD gene in Syrian hamster cells [28]. Furthermore, heat shock also activated latent splicing in tested C. elegans transcripts [33]. It was further shown that exposing Syrian hamster cells to γ irradiation, hypoxia, cold shock, and heat shock elicited latent splicing in endogenous CAD mRNA, with heat shock causing the strongest effect [28]. Therefore, the global effect of heat shock on latent splicing was examined using a splicing-sensitive microarray, revealing activation of splicing in 508 latent sites. It should be pointed out that this number of activated LSSs is a lower limit, because the latent transcript, which contains PTCs, is downregulated by NMD in the cytoplasm [28].

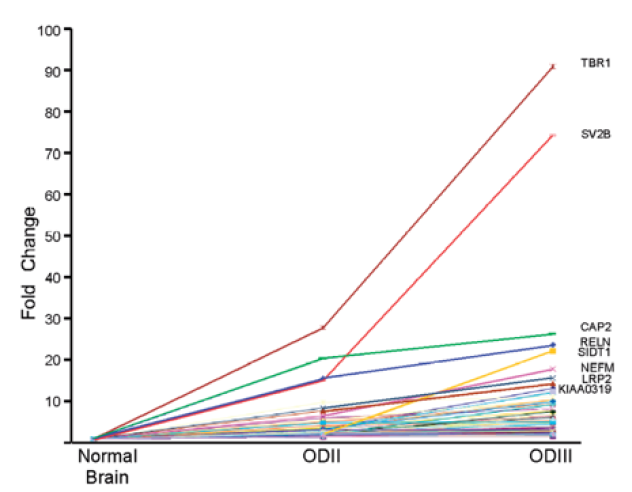

Importantly, SOS is abrogated in cancer, resulting in activation of thousands of LSSs. For female breast cancer, the second most commonly diagnosed and the fifth leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide [48][49][50][51][52], , data mined from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) of MCF-7 breast cancer (BC) cells as compared to MCF-10A non-malignant breast cells [53] was analyzed [28]. The analysis revealed activation of latent splicing in 794 latent sites [28]. Brain cancers are characterized by high morbidity and mortality, owing to their localization and often local invasive growth [54][55]. Gliomas are the most common primary central nervous system tumors in adults, and despite advances in treatments, the prognosis for most glioma patients remains poor [55]. Similar analyses of activation of latent splicing were performed in different types of gliomas, using data available in the GEO database [56]. This analysis revealed that in glioblastoma tumors, 409 latent sites were activated, while in oligodendroglioma (OD) samples the number of activated LSSs were 853 in grade II and 612 in grade III [28]. These mRNAs are from broad functional groups, including mRNAs implicated in cell differentiation and proliferation. Notably, in OD, a correlation was found between the level of activation of latent splicing and the severity of the disease. The analysis revealed 125 mRNAs for which the extent of latent splicing activation was higher in the more aggressive ODIII than in ODII or normal cells (Figure 3), portraying novel markers for OD.

Figure 3. Activation of latent splicing in cancer: Correlation between the level of activation of latent splicing and the severity of OD. The graph depicts fold changes in the level of latent splicing in 125 gene transcripts whose latent splicing expression increased from normal cells to ODII and further increased in ODIII. Names of the top-scoring gene transcripts are indicated [28].

Interesting examples are genes expressing aberrant nonsense mRNAs in both breast cancer and glioma, due to latent splicing activation, signifying novel targets in the fight against cancer [28]. It should be pointed out that abrogation of SOS under stress and in cancer might lead to profound dysregulation of the transcriptome, affecting a large variety of cellular functions, emphasizing transcriptomic instability in addition to the well-known genomic one. Therefore, targeting the unexplored thousands of LSSs that are activated in cancer and encode damaged proteins, having potentially harmful effects on cell metabolism, might lead to novel avenues in cancer diagnostics and treatment.

References

- Lee, Y.; Rio, D.C. Mechanisms and Regulation of Alternative Pre-mRNA Splicing. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2015, 84, 291–323.

- Pan, Q.; Bakowski, M.A.; Morris, Q.; Zhang, W.; Frey, B.J.; Hughes, T.R.; Blencowe, B.J. Alternative splicing of conserved exons is frequently species-specific in human and mouse. Trends Genet. 2005, 21, 73–77.

- Wang, E.T.; Sandberg, R.; Luo, S.; Khrebtukova, I.; Zhang, L.; Mayr, C.; Kingsmore, S.F.; Schroth, G.P.; Burge, C.B. Alternative isoform regulation in human tissue transcriptomes. Nature 2008, 456, 470–476.

- Fiszbein, A.; Kornblihtt, A.R. Alternative splicing switches: Important players in cell differentiation. BioEssays 2017, 39, 39.

- Dvinge, H. Regulation of alternative mRNA splicing: Old players and new perspectives. FEBS Lett. 2018, 592, 2987–3006.

- Kelemen, O.; Convertini, P.; Zhang, Z.; Wen, Y.; Shen, M.; Falaleeva, M.; Stamm, S. Function of alternative splicing. Gene 2013, 514, 1–30.

- El Marabti, E.; Younis, I. The Cancer Spliceome: Reprograming of Alternative Splicing in Cancer. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2018, 5, 80.

- Singh, R.K.; Cooper, T.A. Pre-mRNA splicing in disease and therapeutics. Trends Mol. Med. 2012, 18, 472–482.

- Anczuków, O.; Krainer, A.R. Splicing-factor alterations in cancers. RNA 2016, 22, 1285–1301.

- Qiu, Y.; Lyu, J.; Dunlap, M.; Harvey, S.E.; Cheng, C. A combinatorially regulated RNA splicing signature predicts breast cancer EMT states and patient survival. RNA 2020, 26, 1257–1267.

- Chabot, B.; Shkreta, L. Defective control of pre–messenger RNA splicing in human disease. J. Cell Biol. 2016, 212, 13–27.

- Will, C.L.; Luhrmann, R. Spliceosome structure and function. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011, 3, a003707.

- Papasaikas, P.; Valcárcel, J. The Spliceosome: The Ultimate RNA Chaperone and Sculptor. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2016, 41, 33–45.

- Fica, S.M.; Oubridge, C.; Galej, W.; Wilkinson, M.; Bai, X.-C.; Newman, A.J.; Nagai, K. Structure of a spliceosome remodelled for exon ligation. Nature 2017, 542, 377–380.

- Yan, C.; Wan, R.; Shi, Y. Molecular Mechanisms of pre-mRNA Splicing through Structural Biology of the Spliceosome. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2019, 11, a032409.

- Shi, Y. Mechanistic insights into precursor messenger RNA splicing by the spliceosome. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2017, 18, 655–670.

- Shi, Y. The Spliceosome: A Protein-Directed Metalloribozyme. J. Mol. Biol. 2017, 429, 2640–2653.

- Wilkinson, M.E.; Lin, P.C.; Plaschka, C.; Nagai, K. Cryo-EM Studies of Pre-mRNA Splicing: From Sample Preparation to Model Visualization. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2018, 47, 175–199.

- Plaschka, C.; Newman, A.J.; Nagai, K. Structural Basis of Nuclear pre-mRNA Splicing: Lessons from Yeast. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2019, 11, a032391.

- Babu, M.M.; Luscombe, N.M.; Aravind, L.; Gerstein, M.; Teichmann, S.A. Structure and evolution of transcriptional regulatory net-works. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2004, 14, 283–291.

- Chen M, Manley JL: Mechanisms of alternative splicing regulation: insights from molecular and genomics approaches. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2009, 10:741-754.

- Sperling, R. Small non-coding RNA within the endogenous spliceosome and alternative splicing regulation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2019, 1862, 194406.

- Sperling, R. The nuts and bolts of the endogenous spliceosome. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2016, 8, e1377.

- Azubel, M., Habib, N., Sperling, J., and Sperling, R. (2006). Native spliceosomes assemble with pre-mRNA to form supraspliceosomes. J Mol Biol 356, 955-966. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.08.011.

- Sperling, J., Azubel, M., and Sperling, R. (2008). Structure and Function of the Pre-mRNA Splicing Machine. Structure 16, 1605-1615. Doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.08.011.

- Sperling, J., and Sperling, R. (2017). Structural studies of the endogenous spliceosome - The supraspliceosome. Methods 125, 70-83. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2017.04.005

- Shefer, K., Sperling, J., and Sperling, R. (2014). The supraspliceosome-a multi-task-machine for regulated pre-mRNA processing in the cell nucleus Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal 11, 113-122. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2014.09.008.

- Nevo, Y.; Kamhi, E.; Jacob-Hirsch, J.; Amariglio, N.; Rechavi, G.; Sperling, J.; Sperling, R. Genome-wide activation of latent donor splice sites in stress and disease. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 10980–10994.

- Popp, M.W.-L.; Maquat, L.E. Organizing Principles of Mammalian Nonsense-Mediated mRNA Decay. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2013, 47, 139–165.

- Schweingruber, C.; Rufener, S.C.; Zünd, D.; Yamashita, A.; Mühlemann, O. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay—Mechanisms of substrate mRNA recognition and degradation in mammalian cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1829, 612–623

- Behm-Ansmant, I.; Kashima, I.; Rehwinkel, J.; Sauliere, J.; Wittkopp, N.; Izaurralde, E. mRNA quality control: An ancient machinery recognizes and degrades mRNAs with nonsense codons. FEBS Lett. 2007, 581, 2845–2853.

- Wachtel, C.; Li, B.; Sperling, J.; Sperling, R. Stop codon-mediated suppression of splicing is a novel nuclear scanning mechanism not affected by elements of protein synthesis and NMD. RNA 2004, 10, 1740–1750.

- Nevo, Y.; Sperling, J.; Sperling, R. Heat shock activates splicing at latent alternative 5′ splice sites in nematodes. Nucleus 2015, 6, 225–235.

- He, F.; Jacobson, A. Nonsense-Mediated mRNA Decay: Degradation of Defective Transcripts Is Only Part of the Story. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2015, 49, 339–366.

- Karousis, E.; Nasif, S.; Mühlemann, O. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay: Novel mechanistic insights and biological impact. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2016, 7, 661–682.

- Kurosaki, T.; Maquat, L.E. Nonsense-mediated mRNA decay in humans at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2016, 129, 461–467.

- Li, B.; Wachtel, C.; Miriami, E.; Yahalom, G.; Friedlander, G.; Sharon, G.; Sperling, R.; Sperling, J. Stop codons affect 5′ splice site selection by surveillance of splicing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 5277–5282.

- Kamhi, E.; Raitskin, O.; Sperling, R.; Sperling, J. A potential role for initiator-tRNA in pre-mRNA splicing regulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 11319–11324.

- Mühlemann, O.; Mock-Casagrande, C.S.; Wang, J.; Li, S.; Custódio, N.; Carmo-Fonseca, M.; Wilkinson, M.F.; Moore, M.J. Precursor RNAs Harboring Nonsense Codons Accumulate Near the Site of Transcription. Mol. Cell 2001, 8, 33–43.

- Aoufouchi, S.; Yélamos, J.; Milstein, C. Nonsense Mutations Inhibit RNA Splicing in a Cell-Free System: Recognition of Mutant Codon Is Independent of Protein Synthesis. Cell 1996, 85, 415–422.

- Gersappe, A.; Burger, L.; Pintel, D.J. A premature termination codon in either exon of minute virus of mice P4 promoter-generated pre-mRNA can inhibit nuclear splicing of the intervening intron in an open reading frame-dependent manner. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 22452–22458.

- De Turris, V.; Nicholson, P.; Orozco, R.Z.; Singer, R.H.; Mühlemann, O. Cotranscriptional effect of a premature termination codon revealed by live-cell imaging. RNA 2011, 17, 2094–2107.

- Maquat, L.E. NASty effects on fibrillin pre-mRNA splicing: Another case of ESE does it, but proposals for translation-dependent splice site choice live on. Genes Dev. 2002, 16, 1743–1753.

- Cartegni, L.; Chew, S.L.; Krainer, A. Listening to silence and understanding nonsense: Exonic mutations that affect splicing. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2002, 3, 285–298.

- Shefer, K.; Boulos, A.; Gotea, V.; Arafat, M.; Ben Chaim, Y.; Muharram, A.; Isaac, S.; Eden, A.; Sperling, J.; Elnitski, L.; et al. A novel role for nucleolin in splice site selection. RNA Biol. 2022, 19, 333–352.

- Ugrinova, I.; Petrova, M.; Chalabi-Dchar, M.; Bouvet, P. Multifaceted Nucleolin Protein and Its Molecular Partners in Oncogenesis. Adv. Protein Chem. Struct. Biol. 2018, 111, 133–164.

- Jia, W.; Yao, Z.; Zhao, J.; Guan, Q.; Gao, L. New perspectives of physiological and pathological functions of nucleolin (NCL). Life Sci. 2017, 186, 1–10.

- Polyak, K. Heterogeneity in breast cancer. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 3786–3788.

- Rojas, K.; Stuckey, A. Breast Cancer Epidemiology and Risk Factors. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 59, 651–672.

- Fouad, Y.A.; Aanei, C. Revisiting the hallmarks of cancer. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2017, 7, 1016–1036.

- Feng, Y.; Spezia, M.; Huang, S.; Yuan, C.; Zeng, Z.; Zhang, L.; Ji, X.; Liu, W.; Huang, B.; Luo, W.; et al. Breast cancer development and progression: Risk factors, cancer stem cells, signaling pathways, genomics, and molecular pathogenesis. Genes Dis. 2018, 5, 77–106.

- Loh, H.-Y.; Norman, B.; Lai, K.-S.; Rahman, N.M.A.N.A.; Alitheen, N.B.M.; Osman, M.A. The Regulatory Role of MicroRNAs in Breast Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4940.

- Bitton, D.A.; Okoniewski, M.J.; Connolly, Y.; Miller, C.J. Exon level integration of proteomics and microarray data. BMC Bioinform. 2008, 9, 118.

- Gavrilovic, I.T.; Posner, J.B. Brain metastases: Epidemiology and pathophysiology. J. Neurooncol. 2005, 75, 5–14.

- Jung, E.; Alfonso, J.; Monyer, H.; Wick, W.; Winkler, F. Neuronal signatures in cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2020, 147, 3281–3291.

- French, P.J.; Peeters, J.K.; Horsman, S.; Duijm, E.; Siccama, I.; Bent, M.V.D.; Luider, T.M.; Kros, J.M.; Van Der Spek, P.; Smitt, P.A.S. Identification of Differentially Regulated Splice Variants and Novel Exons in Glial Brain Tumors Using Exon Expression Arrays. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 5635–5642.