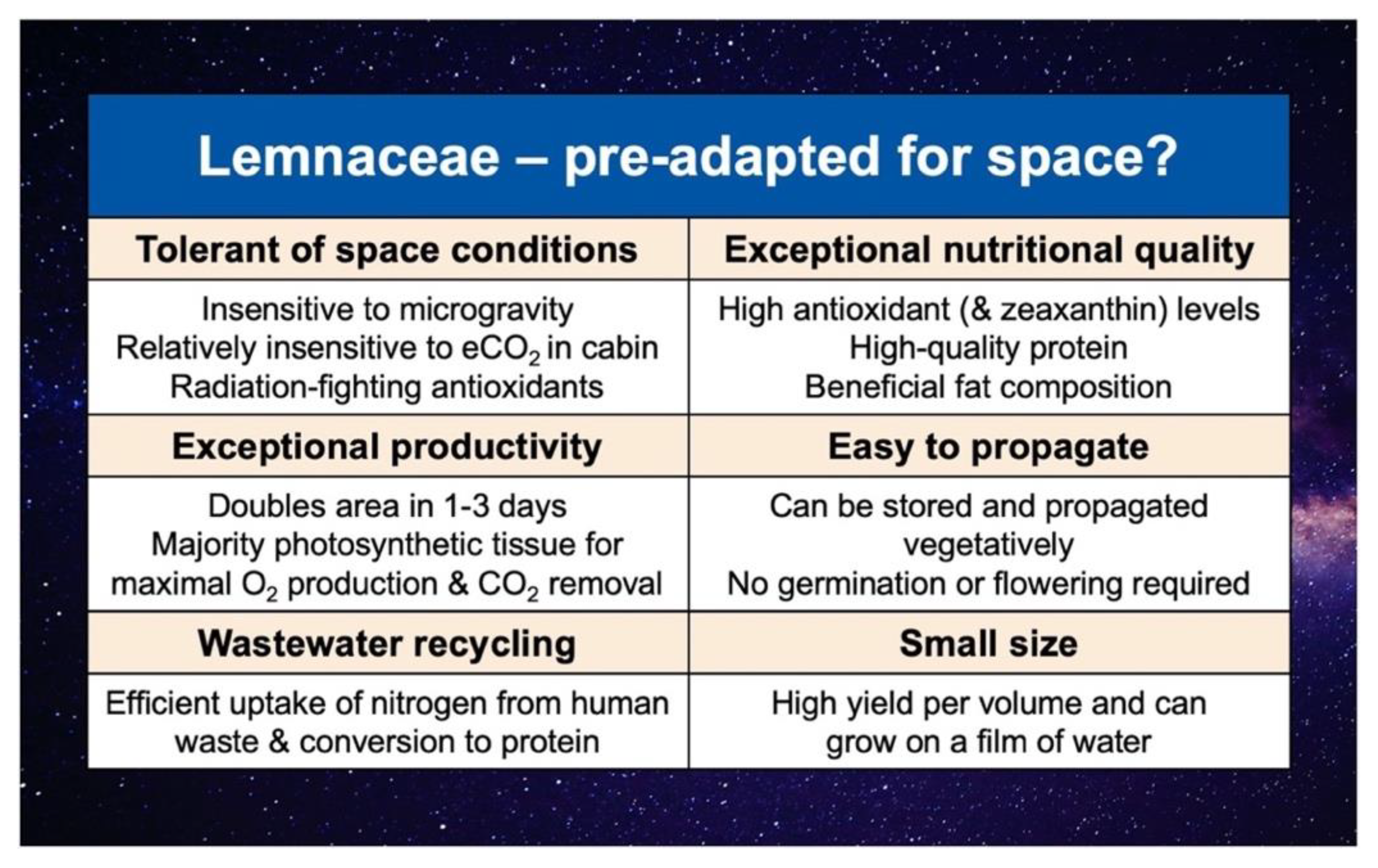

Sustainable long-term space missions require regenerative life support from plants. However, traditional crop plants lack some features desirable for use in space environments. The aquatic plant family Lemnaceae (duckweeds) has enormous potential as a space crop, featuring (i) fast growth, with very high rates of O2 production and CO2 sequestration, (ii) an exceptional nutritional quality (with respect to radiation-fighting antioxidants and high-quality protein), (iii) easy propagation and high productivity in small spaces, and (iv) resilience to the stresses (radiation, microgravity, and elevated CO2) of the human-inhabited space-cabin environment. These attractive traits of Lemnaceae are placed into the context of their unique adaptations to the aquatic environment. In other words, evolution may have led to a group of plants with traits that can be viewed as pre-adaptations for spaceflight environments.

- duckweed

- homeostasis

- Lemnaceae

- reactive oxygen species

1. Introduction

1.1. Molecular Oxygen Plays Unique and Essential Roles for Life

Molecular oxygen (O2) is necessary for much of life on Earth to function. Most of the oxygen in the atmosphere has been produced over the last two billion years by photosynthetic organisms, which supported the evolution of multicellular organisms that depend on aerobic respiration [1][2]. This dependency applies to both heterotrophs and autotrophs, such as plants that can be killed when roots have diminished access to oxygen because of insufficient O2-dependent respiration in water-logged soils [3] (except for specialist plants with unique adaptations facilitating O2 diffusion to the roots[4]).

For space travel and habitation, enough O2 must be transported or continuously generated for long missions to sustain a human crew. Currently, O2 is produced on the International Space Station through the splitting of water by electrolysis [5]. For long human-crewed space missions, plants can serve as a regenerative life support system that continuously produces O2, removes CO2 [6][7], and provides additional essential services.

1.2. Reactive Oxygen Can Kill

While essential for much of life on earth, oxygen is a double-edged sword. The first mass extinction event of biological species was likely caused by the rise in atmospheric O2 levels and has been termed the Great Oxidation Event[8][9]. Today, O2-dependent organisms carefully maintain an internal balance between oxidants and antioxidants (redox homeostasis) [10]. Notably, energy metabolism in chloroplasts and mitochondria (the organellar powerhouses that interact with O2) continuously creates a particularly reactive form of oxygen (reactive oxygen, species, ROS; [10][11]). Whereas ROS are essential in small doses, excess ROS can cause a host of adverse effects (see below). The life-supporting quality of oxygen is thus inextricably linked to its potential dangers.

In small quantities, ROS act as universal regulators of master control genes that orchestrate growth, development, aging, and various metabolic defenses of humans, plants, and many microorganisms [12][13]. For example, ROS can stimulate cell division (by forwarding the cell cycle) as well as trigger the destruction of (typically unwanted or injured) cells in the process of programmed cell death [14][15], both of which can be enhanced to undesirable levels in spaceflight environments [16] (for details, see the next section). One example of an ROS is superoxide (a form of O2 with a single additional electron, i.e, superoxide anion radical, O2●−), which various organisms actively produce to kill pathogens [17] and other unwanted cells. However, excess superoxide can cause excessive cell damage unless redox homeostasis is maintained by keeping ROS in check with antioxidants. A lasting departure from redox homeostasis can cause continuous low-grade activation of the human immune system with system-wide inflammation and a host of resulting diseases, disorders, and dysfunctions. In large quantities, ROS can be lethal. In viral diseases (such as HIV-AIDS and, evidently, COVID-19), snowballing production of ROS and other inflammation-promoting messengers (the cytokine storm) can lead to massive organ damage [18].

2. The Challenges of Space Environments

A major challenge for human utilization of space is exposure to galactic cosmic radiation (GCR). GCR consists of heavy ions/high-density charged particles [16][19] and can generate dangerous amounts of ROS through the splitting of water under the influence of radiation (radiolysis) in all water-containing cells. This ROS can lead to DNA mutations. In addition, GCR can also produce direct DNA breaks (Figure 1; [20]). The effects of GCR-induced ROS on gene regulation are complex and include induction of some protective (e.g., antioxidant) effects as well as negative snowballing effects that further exacerbate ROS production and DNA damage. For example, a feed-forward cycle in space environments involves ROS stimulation of a human ROS-producing enzyme (NADPH oxidase; [21][22]). Specifically, an initial wave of ROS production triggers consecutive waves of ROS production to activate and recruit other immune cells (as may be warranted under pathogen attack [15]). Excess ROS production and DNA damage can thus lead to signaling cascades that produce more and more unwanted ROS (Figure 1).

3. The Multi-Hit Hypothesis: Interaction among Different Stresses in a Space Environment

3.1. Specific Plant Responses

In land plants, a low level of gravity (microgravity) can interfere with plant responses to radiation by inhibiting directional, gravity-dependent signals between shoots and roots [23]. More research is needed into the effect of microgravity in space environments as different species can respond in different ways [24].Elevated CO2 in a confined environment is also a concern. Plants growing under elevated atmospheric CO2 levels can produce excessive levels of ROS (Figure 2), which can lead to an imbalance in redox homeostasis [25]. Specifically, elevated CO2 can enhance ROS production when photosynthesis utilizes the greater level of available CO2 to produce more sugars and starch. This results in a build-up of carbohydrates and a backup of electrons in the photosynthetic electron transport chain. In turn, this backup leads to the transfer of electrons and/or excitation energy to oxygen, forming ROS [25]. Most plants respond to prolonged exposure to elevated CO2 with photosynthetic downregulation because the plant can perform the same rate of photosynthesis (as under lower CO2 levels) with fewer photosynthetic proteins under elevated CO2. CO2 has also been reported to accelerate plant aging (senescence; Figure 2; [26]). In some species, growth can be inhibited by elevated CO2 alone [27], and it is common for elevated CO2 to exacerbate growth penalties imposed by other environmental factors [28][29][30][31].

3.2. Human Physiology

To mitigate the risks associated with spaceflight, it is important to consider multiple lifestyle factors for humans [32]. Diet, physical activity, and psychological stress (Figure 2) all provide inputs into cellular redox homeostasis and thus affect health outcomes [33][34]. For example, whereas regular moderate physical activity triggers the synthesis of endogenous antioxidant enzymes to combat ROS production during exercise, physical inactivity fails to induce antioxidant enzymes [35] and thus fails to counter ROS production (Figure 2). It thus appears that these other factors, which are modifiable to some extent, may either exacerbate or mitigate human exposure to GCR in spaceflight environments.

4. Redox-Based Orchestration of Growth, Development, and Defenses

4.1. Early-Warning Systems for Oxidative Stress

A hallmark of metabolically active cells is that they allow moderate amounts of ROS to play fundamental roles in cellular metabolism and other biological processes [36][37] while avoiding unwanted effects of excess ROS. To support this redox homeostasis, large molecules, including fatty acids-based lipids and proteins, are particularly sensitive to oxidation. These molecules can serve as sentinels, and signal when internal ROS production is rising. For example, membranes surrounding cells contain polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) derived from dietary fats; these membrane components are easily oxidized to oxidation products that serve as gene regulators [38][39]. In humans, immunostimulatory regulators are mainly derived from omega-6 PUFAs and inflammation-resolving regulators mainly from omega-3 PUFAs [40]. In addition, proteins with (thiol) groups that are easily oxidized are also linked to redox-based gene-regulation [41][42][43].

4.2. Gene Regulation by Derivatives of Lipid Peroxidation and the Need for Dietary Antioxidant Metabolites

Just like ROS and their products, antioxidant systems are potent modulators of redox-modulated signaling networks and genes[44]. Dietary membrane-embedded antioxidants keep the formation of PUFA-derived regulators in check and thus control and resolve acute inflammation in humans[45]. Furthermore, a balanced dietary ratio of omega-3 to omega-6 fatty acids is critical to support immunity and avoid non-resolving inflammation.The human brain is particularly susceptible to non-resolving inflammation due to its large complement of biological membranes, and a high level of oxygenation that increases the propensity for PUFA oxidation[46][47][48]. Resulting non-resolving neuroinflammation leads to low cognitive function in otherwise healthy individuals as well as to mental and learning disorders and neurodegenerative diseases[34][49]. Antioxidation is therefore needed to prevent neuroinflammation[34][50].

Whereas a whole suite of diet-derived antioxidant metabolites can provide protection in aqueous (water-based) environments, only a few antioxidants are able to dissolve and provide protection in biological membranes. These latter membrane-soluble (fat-soluble) antioxidants include the antioxidant vitamin E (tocopherol) and carotenoids[34][51][52]. The structure of these molecules determines their orientation in the membrane, and two carotenoids in particular (zeaxanthin and lutein) integrate into biological membranes in a way that can provide stabilization[53] and oppose PUFA oxidation[34][54][55][56]. Zeaxanthin is the more potent antioxidant of the two[57], exhibiting a particularly stabilizing orientation in biological membranes[58].4.3. Zeaxanthin and Lutein Protect Photosynthesis

Unlike humans, plants can make zeaxanthin and lutein from scratch (de novo) for specific roles in the prevention of radiation damage. However, whereas lutein is constitutively present in leafy crops, zeaxanthin is formed only under bright light and quickly removed again when light levels drop in these photosynthetic systems[59]. Only leafy greens harvested and eaten immediately after their exposure to bright light thus deliver significant levels of zeaxanthin. In contrast, leafy green produce purchased at a grocery store provides lutein but little to no zeaxanthin. Moreover, typical edible leafy crops accumulate much less zeaxanthin than the inedible leaves of evergreens[59]. Still, foods other than leaves can provide high levels of zeaxanthin and lutein on earth, including orange peppers, corn, and eggs (Figure 3;[60][61][62][63]). Zeaxanthin was named after the yellow color of an ear of corn (genus Zea, with “xanthos” the Greek word for golden/yellow). While being unable to synthesize carotenoids de novo, most animals do accumulate carotenoids when they have access to carotenoid-containing food[64]. The problem in spaceflight environments, however, is that there won’t be room for a corn field or a chicken farm and that typical edible crops produce very little zeaxanthin when evidence points to a need for human consumption of both zeaxanthin and lutein. As illustrated below (see section 5), aquatic floating plants have the unusual property of accumulating as much and more zeaxanthin as the inedible leaves of evergreen plants.

In addition, zeaxanthin does not act alone in providing the necessary protection for humans. To extend the lifetime of zeaxanthin and vitamin E in membranes, they must be recycled (by other antioxidants donating an electron and re-reducing oxidized zeaxanthin or vitamin E) to prevent them from becoming harmful oxidants themselves (Figure 4; [65][66]). It is thus critical to provide a balanced mix of antioxidant metabolites in the human diet, preferably through the consumption of whole foods rich in multiple essential micronutrients [67]. In contrast, single, high-dose antioxidant supplementation can have negative effects[68]. Specifically, excess dietary consumption of antioxidants from high-dose supplements can lower ROS levels to the extent that essential ROS signals fail to be produced[35]. Due to the benefits of whole food as well as the finite lifetime of vitamin supplements, nutritious crops will be critical to extended space missions.

5. Lemnaceae as Space Crops

5.1. An Unusual Combination of Multiple Attractive Traits

The enormous potential of the aquatic plant family Lemnaceae (duckweeds) as both model species (for, e.g., radiobiology and genomic studies) and edible space crops has been recognized since the beginning of the space program (Figure 5). Lemnaceae were the very first plants studied for photosynthesis in space, grew well under these conditions[69], and have been recommended as a good candidate for bioregenerative life support systems[70][71][72][73]. Additional flight experiments, including NASA STS-4 Getaway Special (1982), Russian satellite Bion 8 (1987), Russian satellite Bion 10 (1992), NASA STS-60 Getaway Special (1994), and STS-67 (1995), indicated that Lemnaceae are also tolerant of the GCR and microgravity encountered in space.

Lemnaceae are consumed around the globe and hailed as a new superfood (e.g.,[74]), and also possess multiple features that make them particularly attractive candidates for space crops (Figure 5). In addition to fast growth, which entails very high rates of O2 production and CO2 removal, Lemnaceae have an exceptional nutritional quality (especially radiation-fighting antioxidants and high-quality protein with all essential amino acids for humans); they are also highly volume-efficient (with particularly small size and the complete or near-complete absence of non-photosynthetic parts) and easy to grow[75].

5.2. Can the Aquatic Lifestyle Be Seen as a Pre-Adaptation for Spaceflight Environments

5.3. Exceptional Antioxidant Content

Duckweed is thus the only known plant that accumulates high levels of zeaxanthin in its photosynthetic organs while also growing very rapidly[76]. Duckweed may also be unique among dietary zeaxanthin sources in providing a particularly well-rounded cocktail of dietary factors that interact synergistically with zeaxanthin in opposing inflammation. Duckweed also has a high content of vitamin E[78][79] and phenolic antioxidants[80][81]. In addition, duckweed has a high ratio of inflammation-resolving omega-3 PUFAs to immunostimulatory omega-6 PUFAs (Figure 5; [82]).

In addition to taking advantage of duckweed’s exceptional propensity to accumulate zeaxanthin, it will be of interest to prevent post-harvest removal of zeaxanthin by suitable environmental conditions and/or natural or engineered mutants.

5.4. Performance under Elevated CO

2

Growth under the elevated CO2 levels, typical of a space cabin environment, was unimpaired in duckweed even under continuous very high light levels that lead to considerable carbohydrate build-up[76]. In contrast, other candidates of leafy vegetable species considered for use on the International Space Station, exhibited decreases in growth, leaf number and leaf area, and biomass under elevated CO2 concentrations[83]. The robustness of Lemnaceae may be related to (i) a relaxation of the controls on growth rate acting in land plants[84] and (ii) preferential use of nitrogen in the form of ammonium over nitrate. It is the use of nitrate as a nitrogen source that can enhance ROS production under elevated CO2[85]. The combination of high nitrate levels and elevated CO2 triggered premature senescence in land plants[28][30][86]. In terms of environmental controls on growth, most land plants quickly curb growth when water or nutrients begin to become limiting, and speed up the completion of the plant life cycle[26]. In contrast, Lemnaceae floating on water and with large nitrogen stores (in the form of storage protein) exhibited unabated growth across a wide range of environmental conditions irrespective of carbohydrate build-up under earth-ambient CO2 levels[77][78].

6. Conclusions

Here we identify the importance as well as the dangers of oxygen and the formation of ROS. Organisms need to maintain a delicate balance between antioxidants and oxidants to support redox homeostasis and signaling in support of growth, development, and stress protection. Some environmental conditions on earth have the potential to disrupt this delicate balance. Moreover, space environments expose plants and astronauts to additional disrupting stresses, such as space radiation in particular but also in addition to other conditions. Identification of plant species with superior rates of production of oxygen and essential human micronutrients as well as the removal of CO2 and recycling of human waste, are essential to the success of future long-term space missions (summarized in Figure 4). Plants of the family Lemnaceae have multiple traits that may help minimize the negative impacts of the combination of stressors encountered in space environments. Unlike land plants, Lemnaceae showed a stimulation, rather than inhibition, of growth under microgravity and exhibited relatively low sensitivity to elevated CO2. Lemnaceae’s exceptional antioxidant content may also reduce its sensitivity to GCR. These attractive genetic traits of Lemnaceae for space environments are features of the plants adapted to the unique aquatic environment.

References

- Berkner, L.V.; Marshall, L.C. On the Origin and Rise of Oxygen Concentration in the Earth’s Atmosphere. J. Atmos. Sci. 1965, 22, 225–261. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0469(1965)022<0225:OTOARO>2.0.CO;2.

- Nursall, J.R. Oxygen as a Prerequisite to the Origin of the Metazoa. Nature 1959, 183, 1170–1172. https://doi.org/10.1038/1831170b0.

- Loreti, E.; Perata, P. The Many Facets of Hypoxia in Plants. Plants 2020, 9, 745. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants9060745.

- Srikanth, S.; Lum, S.K.Y.; Chen, Z. Mangrove Root: Adaptations and Ecological Importance. Trees 2016, 30, 451–465. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00468-015-1233-0.

- Tobias, B.; Garr, J.; Erne, M. International Space Station Water Balance Operations. In Proceedings of the 41st International Conference on Environmental Systems, Portland, OR, USA, 17–21 July 2011; p. 5150.

- Ferl, R.; Wheeler, R.; Levine, H.G.; Paul, A.-L. Plants in Space. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2002, 5, 258–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1369-5266(02)00254-6.

- Fu, Y.; Li, L.; Xie, B.; Dong, C.; Wang, M.; Jia, B.; Shao, L.; Dong, Y.; Deng, S.; Liu, H. How to Establish a Bioregenerative Life Support System for Long-Term Crewed Missions to the Moon or Mars. Astrobiology 2016, 16, 925–936. https://doi.org/10.1089/ast.2016.1477.

- Ligrone, R. The Great Oxygenation Event. In Biological Innovations that Built the World; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 129–154. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-16057-9_5.

- Lyons, T.W.; Reinhard, C.T.; Planavsky, N.J. The Rise of Oxygen in Earth’s Early Ocean and Atmosphere. Nature 2014, 506, 307–315. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13068.

- Brigelius-Flohé, R. Commentary: Oxidative Stress Reconsidered. Genes Nutr. 2009, 4, 161–163.

- Edreva, A. Generation and Scavenging of Reactive Oxygen Species in Chloroplasts: A Submolecular Approach. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2005, 106, 119–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2004.10.022.

- Alfadda, A.A.; Sallam, R.M. Reactive Oxygen Species in Health and Disease. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2012, 2012, 936486. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/936486.

- Fichman, Y.; Mittler, R. Rapid Systemic Signaling during Abiotic and Biotic Stresses: Is the ROS Wave Master of All Trades? Plant J. 2020, 102, 887–896. https://doi.org/10.1111/tpj.14685.

- Cai, Q.; Zhao, M.; Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Nie, Y.; Li, P.; Liu, T.; Ge, R.; Han, F. Reduced Expression of Citrate Synthase Leads to Excessive Superoxide Formation and Cell Apoptosis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 485, 388–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.02.067.

- Forrester, S.J.; Kikuchi, D.S.; Hernandes, M.S.; Xu, Q.; Griendling, K.K. Reactive Oxygen Species in Metabolic and Inflammatory Signaling. Circ. Res. 2018, 122, 877–902. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.311401.

- Gómez, X.; Sanon, S.; Zambrano, K.; Asquel, S.; Bassantes, M.; Morales, J.E.; Otáñez, G.; Pomaquero, C.; Villarroel, S.; Zurita, A.; et al. Key Points for the Development of Antioxidant Cocktails to Prevent Cellular Stress and Damage Caused by Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) during Manned Space Missions. npj Microgravity 2021, 7, 35. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41526-021-00162-8.

- Phan, Q.T.; Sipka, T.; Gonzalez, C.; Levraud, J.-P.; Lutfalla, G.; Nguyen-Chi, M. Neutrophils Use Superoxide to Control Bacterial Infection at a Distance. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, e1007157. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1007157.

- Doitsh, G.; Greene, W.C. Dissecting How CD4 T Cells Are Lost during HIV Infection. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 19, 280–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2016.02.012.

- Datta, K.; Suman, S.; Kallakury, B.V.S.; Fornace, A.J. Exposure to Heavy Ion Radiation Induces Persistent Oxidative Stress in Mouse Intestine. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42224. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0042224.

- Arena, C.; De Micco, V.; Macaeva, E.; Quintens, R. Space Radiation Effects on Plant and Mammalian Cells. Acta Astronaut. 2014, 104, 419–431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actaastro.2014.05.005.

- Pazhanisamy, S.K.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Batinic-Haberle, I.; Zhou, D. NADPH Oxidase Inhibition Attenuates Total Body Irradiation-Induced Haematopoietic Genomic Instability. Mutagenesis 2011, 26, 431–435. https://doi.org/10.1093/mutage/ger001.

- Wang, M.; Zhang, J.; Walker, S.J.; Dworakowski, R.; Lakatta, E.G.; Shah, A.M. Involvement of NADPH Oxidase in Age-Associated Cardiac Remodeling. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2010, 48, 765–772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.01.006.

- Wang, T.; Sun, Q.; Xu, W.; Li, F.; Li, H.; Lu, J.; Wu, L.; Wu, Y.; Liu, M.; Bian, P. Modulation of Modeled Microgravity on Radiation-Induced Bystander Effects in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mutat. Res. 2015, 773, 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2015.01.010.

- Kordyum, E.L. Biology of Plant Cells in Microgravity and under Clinostating. Int. Rev. Cytol. 1997, 171, 1–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0074-7696(08)62585-1.

- Demmig-Adams, B.; Polutchko, S.K.; Zenir, M.C.; Fourounjian, P.; Stewart, J.J.; López-Pozo, M.; Adams, W.W., III. Intersections: Photosynthesis, Abiotic Stress, and the Plant Microbiome. Photosynthetica 2022, 60, 59–69. https://doi.org/10.32615/ps.2021.065.

- Wingler, A.; Henriques, R. Sugars and the Speed of Life—Metabolic Signals That Determine Plant Growth, Development and Death. Physiol. Plant. 2022, 174, e13656. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppl.13656.

- Zhang, Y.; Richards, J.T.; Feiveson, A.H.; Richards, S.E.; Neelam, S.; Dreschel, T.W.; Plante, I.; Hada, M.; Wu, H.; Massa, G.D. Response of Arabidopsis thaliana and Mizuna Mustard Seeds to Simulated Space Radiation Exposures. Life 2022, 12, 144.

- Agüera, E.; De la Haba, P. Leaf Senescence in Response to Elevated Atmospheric CO2 Concentration and Low Nitrogen Supply. Biol. Plant. 2018, 62, 401–408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10535-018-0798-z.

- Tausz‐Posch, S.; Tausz, M.; Bourgault, M. Elevated [CO2] Effects on Crops: Advances in Understanding Acclimation, Nitrogen Dynamics and Interactions with Drought and Other Organisms. Plant Biol. 2020, 22, 38–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/plb.12994.

- Adavi, S.B.; Sathee, L. Elevated CO2 Alters Tissue Balance of Nitrogen Metabolism and Downregulates Nitrogen Assimilation and Signalling Gene Expression in Wheat Seedlings Receiving High Nitrate Supply. Protoplasma 2021, 258, 219–233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00709-020-01564-3.

- Adavi, S.B.; Sathee, L. Elevated CO2 Differentially Regulates Root Nitrate Transporter Kinetics in a Genotype and Nitrate Dose-Dependent Manner. Plant Sci. 2021, 305, 110807. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plantsci.2020.110807.

- Furman, D.; Campisi, J.; Verdin, E.; Carrera-Bastos, P.; Targ, S.; Franceschi, C.; Ferrucci, L.; Gilroy, D.W.; Fasano, A.; Miller, G.W. Chronic Inflammation in the Etiology of Disease across the Life Span. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1822–1832. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-019-0675-0.

- Phillips, C. Lifestyle Modulators of Neuroplasticity: How Physical Activity, Mental Engagement, and Diet Promote Cognitive Health during Aging. Neural Plast. 2017, 2017, 3589271. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/3589271.

- Polutchko, S.K.; Glime, G.N.; Demmig-Adams, B. Synergistic Action of Membrane-Bound and Water-Soluble Antioxidants in Neuroprotection. Molecules 2021, 26, 5385. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26175385.

- Adams, R.B.; Egbo, K.N.; Demmig-Adams, B. High-Dose Vitamin C Supplements Diminish the Benefits of Exercise in Athletic Training and Disease Prevention. Nutr. Food Sci. 2014, 44, 95–101. https://doi.org/10.1108/NFS-03-2013-0038.

- Jackson, M.J. Free Radicals Generated by Contracting Muscle: By-Products of Metabolism or Key Regulators of Muscle Function? Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008, 44, 132–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.06.003.

- Mittler, R. ROS Are Good. Trends Plant Sci. 2017, 22, 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2016.08.002.

- Kuhn, H.; Banthiya, S.; Van Leyen, K. Mammalian Lipoxygenases and Their Biological Relevance. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1851, 308–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.10.002.

- Mosblech, A.; Feussner, I.; Heilmann, I. Oxylipins: Structurally Diverse Metabolites from Fatty Acid Oxidation. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2009, 47, 511–517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2008.12.011.

- DiNicolantonio, J.J.; O’Keefe, J. The Importance of Maintaining a Low Omega-6/Omega-3 Ratio for Reducing the Risk of Inflammatory Cytokine Storms. Mo. Med. 2020, 117, 539–542.

- Dietz, K.-J.; Hell, R. Thiol Switches in Redox Regulation of Chloroplasts: Balancing Redox State, Metabolism and Oxidative Stress. Biol. Chem. 2015, 396, 483–494. https://doi.org/10.1515/hsz-2014-0281.

- Lee, M.H.; Yang, Z.; Lim, C.W.; Lee, Y.H.; Dongbang, S.; Kang, C.; Kim, J.S. Disulfide-Cleavage-Triggered Chemosensors and Their Biological Applications. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 5071–5109. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr300358b.

- Martins, L.; Trujillo-Hernandez, J.A.; Reichheld, J.-P. Thiol Based Redox Signaling in Plant Nucleus. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 705. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2018.00705.

- Noctor, G.; Reichheld, J.-P.; Foyer, C.H. ROS-Related Redox Regulation and Signaling in Plants. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018, 80, 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.07.013.

- Artiach, G.; Sarajlic, P.; Bäck, M. Inflammation and Its Resolution in Coronary Artery Disease: A Tightrope Walk between Omega-6 and Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids. Kardiol. Pol. 2020, 78, 93–95. https://doi.org/10.33963/KP.15202.

- Chang, C.-Y.; Ke, D.-S.; Chen, J.-Y. Essential Fatty Acids and Human Brain. Acta Neurol. Taiwan 2009, 18, 231–241.

- Masamoto, K.; Tanishita, K. Oxygen Transport in Brain Tissue. J. Biomech. Eng. 2009, 131, 074002. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.3184694.

- McNamara, R.K.; Asch, R.H.; Lindquist, D.M.; Krikorian, R. Role of Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids in Human Brain Structure and Function across the Lifespan: An Update on Neuroimaging Findings. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 2018, 136, 23–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plefa.2017.05.001.

- Lyman, M.; Lloyd, D.G.; Ji, X.; Vizcaychipi, M.P.; Ma, D. Neuroinflammation: The Role and Consequences. Neurosci. Res. 2014, 79, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neures.2013.10.004.

- Catorce, M.N.; Gevorkian, G. Evaluation of Anti-Inflammatory Nutraceuticals in LPS-Induced Mouse Neuroinflammation Model: An Update. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2020, 18, 636–654. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570159X18666200114125628.

- Wang, X.; Quinn, P.J. The Location and Function of Vitamin E in Membranes. Mol. Membr. Biol. 2000, 17, 143–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687680010000311.

- Krinsky, N.I.; Johnson, E.J. Carotenoid Actions and Their Relation to Health and Disease. Mol. Asp. Med. 2005, 26, 459–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mam.2005.10.001.

- Gruszecki, W.I.; Strzałka, K. Carotenoids as Modulators of Lipid Membrane Physical Properties. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2005, 1740, 108–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.11.015.

- Sujak, A.; Gabrielska, J.; Grudziński, W.; Borc, R.; Mazurek, P.; Gruszecki, W.I. Lutein and Zeaxanthin as Protectors of Lipid Membranes against Oxidative Damage: The Structural Aspects. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1999, 371, 301–307. https://doi.org/10.1006/abbi.1999.1437.

- Havaux, M.; García-Plazaola, J.I. Beyond Non-Photochemical Fluorescence Quenching: The Overlapping Antioxidant Functions of Zeaxanthin and Tocopherols. In Non-Photochemical Quenching and Energy Dissipation in Plants, Algae and Cyanobacteria; Demmig-Adams, B., Garab, G., Adams, W.W., III, Govindjee, Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 40, pp. 583–603. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9032-1_26.

- Demmig-Adams, B.; Polutchko, S.K.; Adams, W.W., III. Structure-Function-Environment Relationship of the Isomers Zeaxanthin and Lutein. Photochem 2022, 2, 308–325. https://doi.org/10.3390/photochem2020022.

- Havaux, M.; Dall’Osto, L.; Bassi, R. Zeaxanthin Has Enhanced Antioxidant Capacity with Respect to All Other Xanthophylls in Arabidopsis Leaves and Functions Independent of Binding to PSII Antennae. Plant Physiol. 2007, 145, 1506–1520. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.107.108480.

- Grudzinski, W.; Nierzwicki, L.; Welc, R.; Reszczynska, E.; Luchowski, R.; Czub, J.; Gruszecki, W.I. Localization and Orientation of Xanthophylls in a Lipid Bilayer. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9619. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-10183-7.

- Demmig-Adams, B.; Stewart, J.J.; López-Pozo, M.; Polutchko, S.K.; Adams, W.W., III. Zeaxanthin, a Molecule for Photoprotection in Many Different Environments. Molecules 2020, 25, 5825. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25245825.

- Baseggio, M.; Murray, M.; Magallanes‐Lundback, M.; Kaczmar, N.; Chamness, J.; Buckler, E.S.; Smith, M.E.; DellaPenna, D.; Tracy, W.F.; Gore, M.A. Natural Variation for Carotenoids in Fresh Kernels Is Controlled by Uncommon Variants in Sweet Corn. Plant Genome 2020, 13, e20008. https://doi.org/10.1002/tpg2.20008.

- Khoo, H.-E.; Prasad, K.N.; Kong, K.-W.; Jiang, Y.; Ismail, A. Carotenoids and Their Isomers: Color Pigments in Fruits and Vegetables. Molecules 2011, 16, 1710–1738. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules16021710.

- Saini, R.K.; Nile, S.H.; Park, S.W. Carotenoids from Fruits and Vegetables: Chemistry, Analysis, Occurrence, Bioavailability and Biological Activities. Food Res. Int. 2015, 76, 735–750. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2015.07.047.

- Zaheer, K. Hen Egg Carotenoids (Lutein and Zeaxanthin) and Nutritional Impacts on Human Health: A Review. CyTA J. Food 2017, 15, 474–487. https://doi.org/10.1080/19476337.2016.1266033.

- Phelan, D.; Prado-Cabrero, A.; Nolan, J.M. Analysis of Lutein, Zeaxanthin, and Meso-Zeaxanthin in the Organs of Carotenoid-Supplemented Chickens. Foods 2018, 7, 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods7020020.

- Burke, M.; Edge, R.; Land, E.J.; Truscott, T.G. Characterisation of Carotenoid Radical Cations in Liposomal Environments: Interaction with Vitamin C. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2001, 60, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1011-1344(01)00111-7.

- Serbinova, E.; Kagan, V.; Han, D.; Packer, L. Free Radical Recycling and Intramembrane Mobility in the Antioxidant Properties of Alpha-Tocopherol and Alpha-Tocotrienol. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1991, 10, 263–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/0891-5849(91)90033-y.

- Liu, R.H. Potential Synergy of Phytochemicals in Cancer Prevention: Mechanism of Action. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 3479S–3485S. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/134.12.3479S.

- Tran, E.; Demmig‐Adams, B. Vitamins and Minerals: Powerful Medicine or Potent Toxins? Nutr. Food Sci. 2007, 37, 50–60. https://doi.org/10.1108/00346650710726959.

- Ward, C.H.; Wilks, S.S.; Craft, H.L. Effects of Prolonged near Weightlessness on Growth and Gas Exchange of Photosynthetic Plants. Dev. Ind. Microbiol. 1970, 11, 276–295.

- Escobar, C.M.; Escobar, A.C. Duckweed: A Tiny Aquatic Plant with Enormous Potential for Bioregenerative Life Support Systems. In Proceedings of the 47th International Conference on Environmental Systems, Charleston, SC, USA, 16–20 July 2017.

- Yuan, J.; Xu, K. Effects of Simulated Microgravity on the Performance of the Duckweeds Lemna aequinoctialis and Wolffia globosa. Aquat. Bot. 2017, 137, 65–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquabot.2016.11.010.

- Romano, L.E.; Aronne, G. The World Smallest Plants (Wolffia sp.) as Potential Species for Bioregenerative Life Support Systems in Space. Plants 2021, 10, 1896. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10091896.

- Ward, C.H.; Wilks, S.S. Use of Algae and Other Plants in the Development of Life Support Systems. Am. Biol. Teach. 1963, 25, 512–521. https://doi.org/10.2307/4440442.

- Kawamata, Y.; Shibui, Y.; Takumi, A.; Seki, T.; Shimada, T.; Hashimoto, M.; Inoue, N.; Kobayashi, H.; Narita, T. Genotoxicity and Repeated-Dose Toxicity Evaluation of Dried Wolffia globosa Mankai. Toxicol. Rep. 2020, 7, 1233–1241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxrep.2020.09.006.

- Acosta, K.; Appenroth, K.J.; Borisjuk, L.; Edelman, M.; Heinig, U.; Jansen, M.A.; Oyama, T.; Pasaribu, B.; Schubert, I.; Sorrels, S. Return of the Lemnaceae: Duckweed as a Model Plant System in the Genomics and Postgenomics Era. Plant Cell 2021, 33, 3207–3234. https://doi.org/10.1093/plcell/koab189.

- Demmig-Adams, B.; López-Pozo, M.; Polutchko, S.K.; Fourounjian, P.; Stewart, J.J.; Zenir, M.C.; Adams, W.W., III. Growth and Nutritional Quality of Lemnaceae Viewed Comparatively in an Ecological and Evolutionary Context. Plants 2022, 11, 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11020145.

- Stewart, J.J.; Adams, W.W., III; Escobar, C.M.; López-Pozo, M.; Demmig-Adams, B. Growth and Essential Carotenoid Micronutrients in Lemna gibba as a Function of Growth Light Intensity. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 480. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.00480.

- Stewart, J.J.; Adams, W.W., III; López-Pozo, M.; Doherty Garcia, N.; McNamara, M.; Escobar, C.M.; Demmig-Adams, B. Features of the Duckweed Lemna That Support Rapid Growth under Extremes of Light Intensity. Cells 2021, 10, 1481. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10061481.

- Hemminge Natesh, N.; Abbey, L.; Asiedu, S.K. An Overview of Nutritional and Antinutritional Factors in Green Leafy Vegetables. Horticult. Int. J. 2017, 1, 00011. https://doi.org/10.15406/hij.2017.01.00011.

- Diotallevi, C.; Angeli, A.; Vrhovsek, U.; Gobbetti, M.; Shai, I.; Lapidot, M.; Tuohy, K. Measuring Phenolic Compounds in Mankai: A Novel Polyphenol and Amino Rich Plant Protein Source. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2020, 79, E434. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0029665120003821.

- Hu, Z.; Fang, Y.; Yi, Z.; Tian, X.; Li, J.; Jin, Y.; He, K.; Liu, P.; Du, A.; Huang, Y. Determining the Nutritional Value and Antioxidant Capacity of Duckweed (Wolffia arrhiza) under Artificial Conditions. LWT 2022, 153, 112477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2021.112477.

- Mohedano, R.A.; Costa, R.H.; Tavares, F.A.; Belli Filho, P. High Nutrient Removal Rate from Swine Wastes and Protein Biomass Production by Full-Scale Duckweed Ponds. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 112, 98–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2012.02.083.

- Burgner, S.E.; Nemali, K.; Massa, G.D.; Wheeler, R.M.; Morrow, R.C.; Mitchell, C.A. Growth and Photosynthetic Responses of Chinese Cabbage (Brassica rapa L. cv. Tokyo Bekana) to Continuously Elevated Carbon Dioxide in a Simulated Space Station “Veggie” Crop-Production Environment. Life Sci. Space Res. 2020, 27, 83–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lssr.2020.07.007.

- Michael, T.P.; Ernst, E.; Hartwick, N.; Chu, P.; Bryant, D.; Gilbert, S.; Ortleb, S.; Baggs, E.L.; Sree, K.S.; Appenroth, K.J. Genome and Time-of-Day Transcriptome of Wolffia australiana Link Morphological Minimization with Gene Loss and Less Growth Control. Genome Res. 2021, 31, 225–238. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.266429.120.

- Foyer, C.H.; Noctor, G. Redox Regulation in Photosynthetic Organisms: Signaling, Acclimation, and Practical Implications. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009, 11, 861–905. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2008.2177.

- Padhan, B.K.; Sathee, L.; Meena, H.S.; Adavi, S.B.; Jha, S.K.; Chinnusamy, V. CO2 Elevation Accelerates Phenology and Alters Carbon/Nitrogen Metabolism vis-à-vis ROS Abundance in Bread Wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 1061. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.01061.