Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) is expanding towards a low-risk patient category as a result of technical advances and operators’ improved skills. However, the post-TAVR antithrombotic regimen remains challenging. Single antiplatelet therapy appears to be the best compromise when there is no compelling indication for chronic oral anticoagulation. Whether it should be aspirin or clopidogrel is not established. There is no supportive evidence to use oral anticoagulation when there is no established indication for oral anticoagulation other than the TAVR procedure. The gap in evidence as to whether DOACs should be preferred over VKA remains when there is an indication for OACoral anticoagulation (OAC) use. It seems that DOACs are not the same and randomized trials are awaited. Likewise, whether oral anticoagulant therapy should be continued or interrupted during the procedure remains unclear.

- TAVR

- antithrombotic therapy

- oral anticoagulation

- DOAC

- VKA

- SAPT

1. Bleeding Events after TAVR

2. Periprocedural Antithrombotic Therapy

Bleeding events have a dreadful impact on TAVR patients and mostly occur within the 30 days post-intervention with great risk during the procedure, as well as ischemic stroke and TIA. Optimal periprocedural antithrombotic strategy is the first key step. The BRAVO-3 trial showed no reduction of major thromboembolic events (4.1% vs. 4.1%, p = 0.97), but a higher rate of major vascular complications (11.9% vs. 7.1%, p = 0.02) with pre-loading clopidogrel on top of aspirin prior to TAVR [127][17]. Low-dose aspirin alone is the treatment of choice, usually started pre-TAVR, in patients with no indication of OAC [2][18]. Parenteral anticoagulation therapy with unfractionated heparin (UFH) is routinely given to prevent periprocedural thromboembolism, particularly stroke. In the BRAVO-3 trial, bivalirudin did not reduce major bleeding or adverse cardiovascular events at 48 h when compared with UFH [128][19]. In 2012, an expert consensus document recommended heparin administration to maintain an activated clotting time (ACT) >300 s [89][20]. More recently, the consensus document of the ESC and the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Intervention (EAPCI) recommend the use of UFH with an ACT between 250 and 300 s to prevent catheter thrombosis and thromboembolism, with bivalirudin an option if there is prior evidence of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia [129][21]. Baseline ACT-guided heparin administration has been shown to reduce major bleeding during transfemoral TAVR [130][22]. Expert consensus documents also suggest that protamine sulfate can be used to reverse anticoagulation before closure to reduce vascular access-site complications and bleeding. Indeed, a significant decrease of major and life-threatening bleeding is obtained with protamine sulfate after TAVR, without a rise in the occurrence of stroke and MI [131][23].3. Antithrombotic Therapy after TAVR

3.1. Antiplatelet Therapy after TAVR: Updated Guidelines in 2021

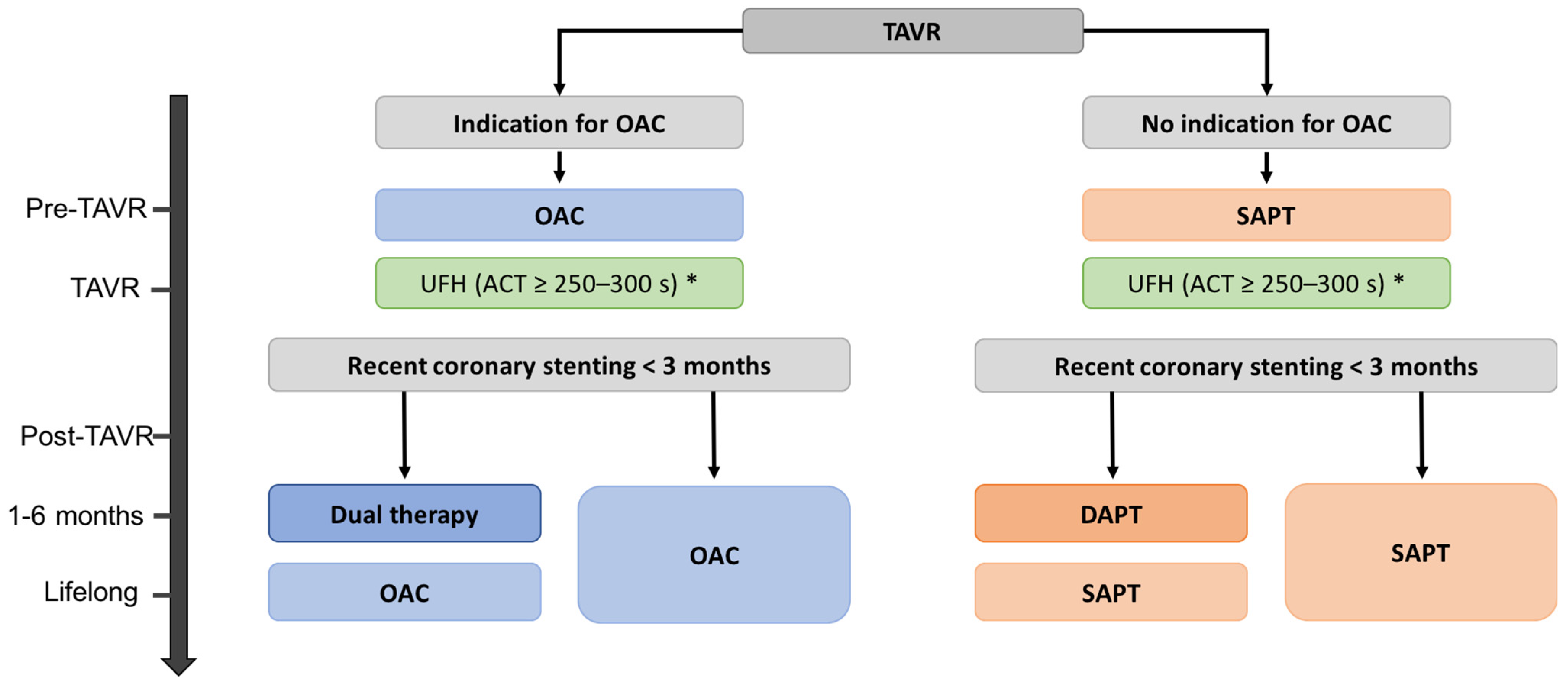

Since 2020, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines recommend a single antiplatelet therapy of aspirin (75–100mg daily) after TAVR in the absence of other indications for oral anticoagulants (class of recommendation: 2a, level of evidence: B-R), while dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin 75–100 mg plus clopidogrel 75 mg daily) for 3 to 6 months has been retroceded to class of recommendation 2b [3][24] (Table 1). Indeed, after years of debate, recent RCTs showed no advantage of DAPT when compared to SAPT in patients undergoing TAVR with no indication of OAC and no prior coronary stenting. Two small-scale RCTs did not report difference between SAPT and DAPT after TAVR on ischemic outcomes in this population [135,136][25][26]. Consistently, the ARTE (Aspirin Versus Aspirin plus Clopidogrel as Antithrombotic Treatment Following TAVI) trial reported no difference between SAPT and DAPT in the occurrence of death, stroke or TIA at 3 months post TAVR, whereas DAPT was associated with a higher rate of major or life-threatening bleeding events (10.8% vs. 3.6% in the SAPT group, p = 0.038) [137][27]. These results were corroborated by the recent Cohort A of the POPular TAVI (Antiplatelet Therapy for Patients Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation) trial, in which 665 patients with no indication for OAC were randomized to receive either aspirin alone or aspirin plus clopidogrel for 3 months after TAVR. Bleeding events and the composite end point of bleeding or thromboembolic events at one year were significantly less frequent with aspirin alone than with DAPT (15.1% vs 26.6%, respectively, relative risk (RR) 0.57; 95% CI: 0.42-0.77; p = 0.001 for bleeding; 23.0% vs 31.1% p <0.001 for noninferiority; RR = 0.74 p = 0.04 for superiority, for composite of bleeding or thromboembolic events) [138][28]. In addition, 2 recent meta-analyses reported lower bleeding events with aspirin alone when compared to DAPT after TAVR without significant differences in mortality, myocardial infarction or stroke [139,140][29][30]. Thus, these studies demonstrate no difference between SAPT and DAPT in preventing thromboembolic outcomes after TAVR in patients with no indication of OAC, but a consistent and significant increase in major bleeding events with DAPT. Taking these results into consideration, guidelines from the ESC and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) on valvular heart disease were updated in 2021, and from this point, a lifelong single antiplatelet therapy with aspirin (75–100 mg daily) or clopidogrel (75 mg daily) is recommended after TAVR in patients with no baseline indications for OAC (class of recommendation: I, level of evidence: A). DAPT with low dose aspirin (75–100 mg daily) plus clopidogrel (75 mg daily) is recommended after TAVR only in case of recent coronary stenting (< 3 months), with duration according to bleeding risk (between 1 and 6 months), followed by a lifelong SAPT [2][18] (Table 1, Figure 61).

5.2. In Antiplatelet Monotherapy, Use of Aspirin or Anti-P2Y12?

| Guidelines and Expert Consensus | Recommendations | Class of Recommendation | Level of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESC/EACTS 2021 Guidelines [18] | |||

| Patients without underlying indication for chronic OAC | |||

| Lifelong single antiplatelet therapy (aspirin 75–100 mg daily or clopidogrel 75mg daily) is recommended after TAVR in patients with no baseline indication for OAC | I | A | |

| Routine use OAC is not recommended in patients with no baseline indication for OAC | III | B | |

| Patients with underlying indication for chronic OAC | |||

| OAC is recommended lifelong for TAVR patients who have other indications for OAC | I | B | |

| AHA/ACC 2020 Guidelines [24] | |||

| Patients without underlying indication for chronic OAC | |||

| For patients with a bioprosthetic TAVR, aspirin 75–100 mg daily is reasonable in the absence of other indications for oral anticoagulants. | IIa | B-R | |

| For patients with a bioprosthetic TAVR who are at low risk of bleeding, dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin 75–100 mg and clopidogrel 75 mg may be reasonable for 3–6 months after valve implantation. | IIb | B-NR | |

| For patients with a bioprosthetic TAVR who are at low risk of bleeding, anticoagulation with a VKA to achieve an INR of 2.5 may be reasonable for at least 3 months after valve implantation. | IIb | B-NR | |

| For patients with a bioprosthetic TAVR, treatment with low-dose rivaroxaban (10 mg daily) plus aspirin (75-100 mg) is contraindicated in absence of other indications for oral anticoagulants. | III | B-R | |

| Patients with underlying indication for chronic OAC | |||

| No specific recommendation | |||

| CCS 2019 Position Statement [31] | |||

| Patients without underlying indication for chronic OAC | |||

| Lifelong aspirin 75–100 mg daily | Expert consensus | ||

| In patients with a recent PCI, dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin 75–100 mg/d plus clopidogrel 75 mg/d) may be continued as per the treating physician | Expert consensus | ||

| Patients with underlying indication for chronic OAC | |||

| DOAC for patients with atrial fibrillation unless contra-indicated* in addition to aspirin for TAVR patients | Expert consensus | ||

| Oral anticoagulation for other indications as per standard guidelines | Expert consensus | ||

| It is prudent to avoid triple therapy in patients at increased risk of bleeding. | Expert consensus | ||

| ACCF/AATS/SCAI/STS 2012 Expert Consensus [20] | |||

| Patients without underlying indication for chronic OAC | |||

| Antiplatelet therapy for at least 3–6 months after TAVR is recommended to decrease the risk of thrombotic or thromboembolic complications | Expert consensus | ||

| Patients with underlying indication for chronic OAC | |||

| In patients treated with warfarin, a direct thrombin inhibitor, or factor Xa inhibitor, it is reasonable to continue low-dose aspirin, but other antiplatelet therapy should be avoided, if possible | Expert consensus | ||

| ACCP-2012 Clinical practice guidelines [32] | |||

| Patients without underlying indication for chronic OAC | |||

| Aspirin (50–100 mg/d) plus clopidogrel (75 mg/d) over VKA therapy and over no platelet therapy in the first 3 months | 2 | C | |

| Patients with underlying indication for chronic OAC | |||

| No specific recommendation | |||

3.2. In Antiplatelet Monotherapy, Use of Aspirin or Anti-P2Y12?

5.3. Patients with Life-Long Indication for Anticoagulation

3.3. Patients with Life-Long Indication for Anticoagulation

In patients requiring long-term OAC, previous observational studies have compared outcomes between OAC alone vs. OAC plus antiplatelet therapy. Rates of stroke and mortality were similar between the two antithrombotic regimens, while there was an increased risk of bleeding complications with OAC plus APT [48,145,146][37][38][39]. Conversely, the analysis of the PARTNER 2 cohort by Kosmidou et al. questioned the efficacy of OAC alone in the prevention of stroke after TAVR, showing that the 2-year stroke incidence was not reduced with OAC alone, while antiplatelet with or without anticoagulant therapy reduced the risk of stroke at 2 years. However, OAC alone was associated with a reduced risk of combined death and stroke [147][40]. More recently, cohort B of the POPular-TAVI trial randomized 313 patients to receive OAC (direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) or VKA) alone or OAC plus clopidogrel for 3 months. The 1-year incidence of bleeding post-TAVI was significantly higher with OAC plus clopidogrel than with OAC alone (34.6% vs. 21.7%, respectively; p = 0.01), while the composite endpoint of death from cardiovascular cause and thromboembolic complications (MI and stroke) appeared non-inferior between the two groups [148][41]. Thus, an association of OAC plus antiplatelet therapy leads to a higher rate of bleeding complications with no advantage in long-term thromboembolic complications. Based on these results, OAC alone is recommended by the ESC/EACTS guidelines after TAVR for patients with a lifelong indication of OAC (class of recommendation: I, level of evidence: B), if no concomitant or recent PCI. In the case of coronary stenting in the past 3 months or concomitant to the valve intervention, dual therapy consisting of OAC plus aspirin (or clopidogrel) is recommended for 1 to 6 months according to the bleeding risk, then switched to life-long anticoagulation [2][18] (Figure 6). No specific recommendations are provided in the ACC/AHA Guidelines for patients undergoing TAVR and requiring long-term OAC.5.4. In Patients Requiring OAC, Which Anticoagulant to Choose?

3.4. In Patients Requiring OAC, Which Anticoagulant to Choose?

Whether DOAC can be used instead of VKA in patients undergoing TAVR and requiring OAC is a matter of debate. The use of DOACs has been widely approved in patients with nonvalvular AF, with proven noninferiority versus VKA in the prevention of thromboembolic events for dabigatran, rivaroxaban and edoxaban [151[42][43][44],152,153], and superiority for apixaban, with lower rate of bleeding events [154][45]. In comparison with warfarin, DOACs reduce the risk of stroke, systemic embolism and intracranial hemorrhage in AF patients with valvular heart disease (VHD) (with the exception of severe mitral stenosis or mechanical heart valve) [155][46]. Furthermore, the North American Consensus Statements have recently been updated and DOAC is the treatment of choice in AF patients undergoing PCI [156][47]. AF is frequent in TAVR patients and associated with poorer outcomes. Furthermore, OAC is a correlated to mortality independently of AF in this population [113][48]. Observational studies comparing DOACs with VKA provided inconsistent findings [157,158,159,160][49][50][51][52]. In the combined France-TAVI and France-2 registries, 8962 patients were treated with OAC after TAVR (24% on DAOCs, 77% on VKAs). After 3 years of follow-up, after propensity matching, there was a significant increase of 37% in mortality rates (VKA vs. DOAC: 35.6% vs. 31.2%; p < 0.005) and 64% in major bleeding (12.3% vs. 8.4%; p < 0.005) with VKAs compared to DOACs. No between-group difference on ischemic stroke and acute coronary syndrome was reported [161][53]. Consistently, the STS/ACC registry, the largest to date with 21,131 patients undergoing TAVR with pre-existing or incident AF discharged on OAC, demonstrated a significantly lower incidence of death in patients on DOACs versus VKAs (15.8% vs. 18.2%, respectively; adjusted hazard ratio (HR) 0.92; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.85–1.00; p = 0.043). In addition, DOACs were also associated with a 19% decrease in bleeding rates compared to VKAs (11.9% vs. 15.0%, respectively; adjusted HR 0.81; 95% CI, 0.33–0.87; p < 0.001). The 1-year incidence of ischemic stroke was similar between the two groups [162][54]. Moreover, in a recent meta-analysis of 12 studies, including patients with an indication for OAC, DOACs were associated with lower all-cause mortality compared to VKAs after more than 1 year of follow-up (RR = 0.64; 95% CI 0.42–0.96; p = 0.03), while no between-group difference was shown in stroke and valve thrombosis rates [163][55]. Conversely, in one nonrandomized study, the composite outcome of any cerebrovascular events, myocardial infarction and all-cause mortality was 44% higher in the DOAC group vs. VKA (21.2% vs. 15.0%, respectively; HR 1.44; p = 0.05). Nevertheless, the 1-year incidence of all-cause mortality was comparable between the two groups (16.5% vs. 12.2% for DOAC and VKA, respectively; HR: 1.36; 95% CI: 0.90–2.06; p= 0.136). Bleeding rates were also similar between the two groups [164][56]. Of note, the increase of ischemic events was of borderline statistical significance. These findings could be the result of heterogeneity in baseline and procedural characteristics, considering the absence of randomization, and the higher prevalence or renal impairment and peripheral vascular among patients treated with NOAC. Furthermore, previously described observational studies and large registries did not correlate with these findings. Thus, in observational and large registries, DOACs seems to provide similar efficacy to VKA in the prevention of stroke, but improvement in the rates of mortality and bleeding, which could favor the use of DOACs after TAVR in patients with an underlying indication of OAC. However, these data from non-randomized studies should be carefully interpreted.5.5. Patients without Underlying Indication for Anticoagulation

3.5. Patients without Underlying Indication for Anticoagulation

Considering the high risk of thromboembolic complications following TAVR and the potential development of subclinical obstructive valve thrombosis, post-TAVR OAC has been tested in the absence of other indications for anticoagulation. The GALILEO trial compared 3 months administration of low dose rivaroxaban (10 mg daily) plus aspirin followed by rivaroxaban alone with 3 months of aspirin plus clopidogrel followed by aspirin alone. The trial was terminated prematurely, with treatment with rivaroxaban being associated with a significantly higher risk of all-cause death (increase of 69%), of thromboembolic complications and of VARC-2 major, disabling or life-threatening bleeding (increase of 50%), compared to antiplatelet therapy [150][57]. Consistently, in the Stratum 2 of the ATLANTIS trial, treatment with apixaban resulted in higher all-cause and non-cardiovascular mortality compared with SAPT or DAPT among patients without an indication of OAC [115][58]. Similar results were reported in An et al. meta-analysis [162][54]. In the ESC/EACTS guidelines, OAC is contraindicated after TAVR in patients with no indications of OAC (class of recommendation: III, level of evidence: B) [2][18].5.6. Ongoing Trials Evaluating Antithrombotic Therapy after TAVR

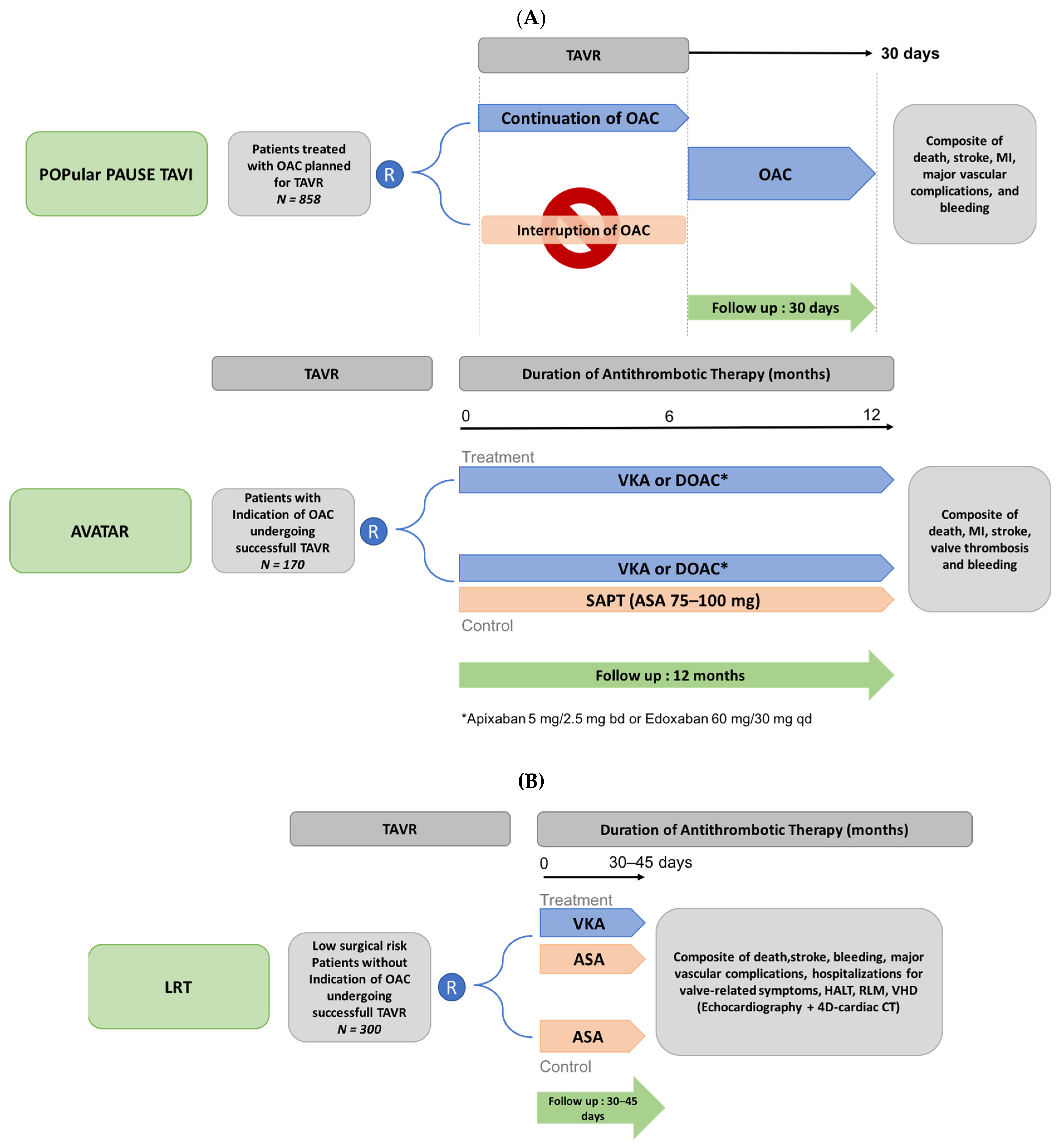

3.6. Ongoing Trials Evaluating Antithrombotic Therapy after TAVR

The main ongoing trials evaluating the antithrombotic regimen in TAVR patients are summarized in Figure 72. The AVATAR (Anticoagulation Alone Versus Anticoagulation and Aspirin Following Transcatheter Aortic Valve Interventions) open-label randomized controlled trial (n = 170) will evaluate the safety and efficacy of anticoagulant therapy alone (VKA or DOAC) versus anticoagulant plus aspirin (NCT02735902) in patients requiring OAC who underwent successful TAVR, after a 12-month follow-up. This trial is expected to end in April 2023. The POPular PAUSE TAVI randomized trial previously cited will provide information on the optimal anticoagulant strategy to adopt during the TAVR procedure, with a comparison of the effect of peri-operative discontinuation versus continuation of OAC on VARC-2 ischemic and bleeding outcomes in patients undergoing TAVR with prior OAC therapy (NCT04437303). Finally, in low-risk patients undergoing TAVR with no indication for OAC, the ongoing LRT (Strategies to Prevent Transcatheter Heart Valve Dysfunction in Low Risk Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement) trial is currently exploring the effect of VKA in addition to aspirin, compared to aspirin only, on clinical outcomes and valvular heart deterioration (NCT03557242, with the estimation completion date in July 2023).

References

- Levett, J.Y.; Windle, S.B.; Filion, K.B.; Brunetti, V.C.; Eisenberg, M.J. Meta-Analysis of Transcatheter Versus Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement in Low Surgical Risk Patients. Am. J. Cardiol. 2020, 125, 1230–1238.

- Kappetein, A.P.; Head, S.J.; Généreux, P.; Piazza, N.; van Mieghem, N.M.; Blackstone, E.H.; Brott, T.G.; Cohen, D.J.; Cutlip, D.E.; van Es, G.-A.; et al. Updated Standardized Endpoint Definitions for Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation: The Valve Academic Research Consortium-2 Consensus Document (VARC-2). Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2012, 42, S45–S60.

- Varc-3 Writing Committee; Généreux, P.; Piazza, N.; Alu, M.C.; Nazif, T.; Hahn, R.T.; Pibarot, P.; Bax, J.J.; Leipsic, J.A.; Blanke, P.; et al. Valve Academic Research Consortium 3: Updated Endpoint Definitions for Aortic Valve Clinical Research. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 1825–1857.

- Piccolo, R.; Pilgrim, T.; Franzone, A.; Valgimigli, M.; Haynes, A.; Asami, M.; Lanz, J.; Räber, L.; Praz, F.; Langhammer, B.; et al. Frequency, Timing, and Impact of Access-Site and Non-Access-Site Bleeding on Mortality among Patients Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2017, 10, 1436–1446.

- Popma, J.J.; Deeb, G.M.; Yakubov, S.J.; Mumtaz, M.; Gada, H.; O’Hair, D.; Bajwa, T.; Heiser, J.C.; Merhi, W.; Kleiman, N.S.; et al. Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replacement with a Self-Expanding Valve in Low-Risk Patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1706–1715.

- Mack, M.J.; Leon, M.B.; Thourani, V.H.; Makkar, R.; Kodali, S.K.; Russo, M.; Kapadia, S.R.; Malaisrie, S.C.; Cohen, D.J.; Pibarot, P.; et al. Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replacement with a Balloon-Expandable Valve in Low-Risk Patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1695–1705.

- Leon, M.B.; Smith, C.R.; Mack, M.; Miller, D.C.; Moses, J.W.; Svensson, L.G.; Tuzcu, E.M.; Webb, J.G.; Fontana, G.P.; Makkar, R.R.; et al. Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Implantation for Aortic Stenosis in Patients Who Cannot Undergo Surgery. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 1597–1607.

- Smith, C.R.; Leon, M.B.; Mack, M.J.; Miller, D.C.; Moses, J.W.; Svensson, L.G.; Tuzcu, E.M.; Webb, J.G.; Fontana, G.P.; Makkar, R.R.; et al. Transcatheter versus Surgical Aortic-Valve Replacement in High-Risk Patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 2187–2198.

- Adams, D.H.; Popma, J.J.; Reardon, M.J.; Yakubov, S.J.; Coselli, J.S.; Deeb, G.M.; Gleason, T.G.; Buchbinder, M.; Hermiller, J.; Kleiman, N.S.; et al. Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replacement with a Self-Expanding Prosthesis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 370, 1790–1798.

- Thyregod, H.G.H.; Steinbrüchel, D.A.; Ihlemann, N.; Nissen, H.; Kjeldsen, B.J.; Petursson, P.; Chang, Y.; Franzen, O.W.; Engstrøm, T.; Clemmensen, P.; et al. Transcatheter Versus Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement in Patients with Severe Aortic Valve Stenosis: 1-Year Results from the All-Comers NOTION Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015, 65, 2184–2194.

- Leon, M.B.; Smith, C.R.; Mack, M.J.; Makkar, R.R.; Svensson, L.G.; Kodali, S.K.; Thourani, V.H.; Tuzcu, E.M.; Miller, D.C.; Herrmann, H.C.; et al. Transcatheter or Surgical Aortic-Valve Replacement in Intermediate-Risk Patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 374, 1609–1620.

- Reardon, M.J.; Van Mieghem, N.M.; Popma, J.J.; Kleiman, N.S.; Søndergaard, L.; Mumtaz, M.; Adams, D.H.; Deeb, G.M.; Maini, B.; Gada, H.; et al. Surgical or Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replacement in Intermediate-Risk Patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 1321–1331.

- Généreux, P.; Cohen, D.J.; Mack, M.; Rodes-Cabau, J.; Yadav, M.; Xu, K.; Parvataneni, R.; Hahn, R.; Kodali, S.K.; Webb, J.G.; et al. Incidence, Predictors, and Prognostic Impact of Late Bleeding Complications after Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 64, 2605–2615.

- Wang, J.; Yu, W.; Jin, Q.; Li, Y.; Liu, N.; Hou, X.; Yu, Y. Risk Factors for Post-TAVI Bleeding According to the VARC-2 Bleeding Definition and Effect of the Bleeding on Short-Term Mortality: A Meta-Analysis. Can. J. Cardiol. 2017, 33, 525–534.

- Borz, B.; Durand, E.; Godin, M.; Tron, C.; Canville, A.; Litzler, P.-Y.; Bessou, J.-P.; Cribier, A.; Eltchaninoff, H. Incidence, Predictors and Impact of Bleeding after Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation Using the Balloon-Expandable Edwards Prosthesis. Heart 2013, 99, 860–865.

- Kochman, J.; Rymuza, B.; Huczek, Z.; Kołtowski, Ł.; Ścisło, P.; Wilimski, R.; Ścibisz, A.; Stanecka, P.; Filipiak, K.J.; Opolski, G. Incidence, Predictors and Impact of Severe Periprocedural Bleeding According to VARC-2 Criteria on 1-Year Clinical Outcomes in Patients After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation. Int. Heart J. 2016, 57, 35–40.

- Nijenhuis, V.J.; Ten Berg, J.M.; Hengstenberg, C.; Lefèvre, T.; Windecker, S.; Hildick-Smith, D.; Kupatt, C.; Van Belle, E.; Tron, C.; Hink, H.U.; et al. Usefulness of Clopidogrel Loading in Patients Who Underwent Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation (from the BRAVO-3 Randomized Trial). Am. J. Cardiol. 2019, 123, 1494–1500.

- Vahanian, A.; Beyersdorf, F.; Praz, F.; Milojevic, M.; Baldus, S.; Bauersachs, J.; Capodanno, D.; Conradi, L.; De Bonis, M.; De Paulis, R.; et al. 2021 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the Management of Valvular Heart Disease. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 43, 561–632.

- Dangas, G.D.; Lefèvre, T.; Kupatt, C.; Tchetche, D.; Schäfer, U.; Dumonteil, N.; Webb, J.G.; Colombo, A.; Windecker, S.; Ten Berg, J.M.; et al. Bivalirudin Versus Heparin Anticoagulation in Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: The Randomized BRAVO-3 Trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015, 66, 2860–2868.

- Holmes, D.R.; Mack, M.J.; Kaul, S.; Agnihotri, A.; Alexander, K.P.; Bailey, S.R.; Calhoon, J.H.; Carabello, B.A.; Desai, M.Y.; Edwards, F.H.; et al. 2012 ACCF/AATS/SCAI/STS Expert Consensus Document on Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2012, 59, 1200–1254.

- Ten Berg, J.; Sibbing, D.; Rocca, B.; Van Belle, E.; Chevalier, B.; Collet, J.-P.; Dudek, D.; Gilard, M.; Gorog, D.A.; Grapsa, J.; et al. Management of Antithrombotic Therapy in Patients Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation: A Consensus Document of the ESC Working Group on Thrombosis and the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI), in Collaboration with the ESC Council on Valvular Heart Disease. Eur. Heart. J. 2021, 42, 2265–2269.

- Bernelli, C.; Chieffo, A.; Montorfano, M.; Maisano, F.; Giustino, G.; Buchanan, G.L.; Chan, J.; Costopoulos, C.; Latib, A.; Figini, F.; et al. Usefulness of Baseline Activated Clotting Time—Guided Heparin Administration in Reducing Bleeding Events during Transfemoral Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2014, 7, 140–151.

- Al-Kassou, B.; Kandt, J.; Lohde, L.; Shamekhi, J.; Sedaghat, A.; Tabata, N.; Weber, M.; Sugiura, A.; Fimmers, R.; Werner, N.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Protamine Administration for Prevention of Bleeding Complications in Patients Undergoing TAVR. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2020, 13, 1471–1480.

- Otto, C.M.; Nishimura, R.A.; Bonow, R.O.; Carabello, B.A.; Erwin, J.P.; Gentile, F.; Jneid, H.; Krieger, E.V.; Mack, M.; McLeod, C.; et al. 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients with Valvular Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2021, 143, e72–e227.

- Ussia, G.P.; Scarabelli, M.; Mulè, M.; Barbanti, M.; Sarkar, K.; Cammalleri, V.; Immè, S.; Aruta, P.; Pistritto, A.M.; Gulino, S.; et al. Dual Antiplatelet Therapy versus Aspirin Alone in Patients Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation. Am. J. Cardiol. 2011, 108, 1772–1776.

- Stabile, E.; Pucciarelli, A.; Cota, L.; Sorropago, G.; Tesorio, T.; Salemme, L.; Popusoi, G.; Ambrosini, V.; Cioppa, A.; Agrusta, M.; et al. SAT-TAVI (Single Antiplatelet Therapy for TAVI) Study: A Pilot Randomized Study Comparing Double to Single Antiplatelet Therapy for Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation. Int. J. Cardiol. 2014, 174, 624–627.

- Rodés-Cabau, J.; Masson, J.-B.; Welsh, R.C.; Garcia Del Blanco, B.; Pelletier, M.; Webb, J.G.; Al-Qoofi, F.; Généreux, P.; Maluenda, G.; Thoenes, M.; et al. Aspirin Versus Aspirin Plus Clopidogrel as Antithrombotic Treatment Following Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement with a Balloon-Expandable Valve: The ARTE (Aspirin Versus Aspirin + Clopidogrel Following Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation) Randomized Clinical Trial. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2017, 10, 1357–1365.

- Brouwer, J.; Nijenhuis, V.J.; Delewi, R.; Hermanides, R.S.; Holvoet, W.; Dubois, C.L.F.; Frambach, P.; De Bruyne, B.; van Houwelingen, G.K.; Van Der Heyden, J.A.S.; et al. Aspirin with or without Clopidogrel after Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Implantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1447–1457.

- Ullah, W.; Zghouzi, M.; Ahmad, B.; Biswas, S.; Zaher, N.; Sattar, Y.; Pacha, H.M.; Goldsweig, A.M.; Velagapudi, P.; Fichman, D.L.; et al. Meta-Analysis Comparing the Safety and Efficacy of Single vs. Dual Antiplatelet Therapy in Post Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation Patients. Am. J. Cardiol. 2021, 145, 111–118.

- Guedeney, P.; Sorrentino, S.; Mesnier, J.; De Rosa, S.; Indolfi, C.; Zeitouni, M.; Kerneis, M.; Silvain, J.; Montalescot, G.; Collet, J.-P. Single Versus Dual Antiplatelet Therapy Following TAVR: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2021, 14, 234–236.

- Asgar, A.W.; Ouzounian, M.; Adams, C.; Afilalo, J.; Fremes, S.; Lauck, S.; Leipsic, J.; Piazza, N.; Rodes-Cabau, J.; Welsh, R.; et al. 2019 Canadian Cardiovascular Society Position Statement for Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation. Can. J. Cardiol. 2019, 35, 1437–1448.

- Whitlock, R.P.; Sun, J.C.; Fremes, S.E.; Rubens, F.D.; Teoh, K.H. Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy for Valvular Disease: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th Ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest 2012, 141, e576S–e600S.

- Kobari, Y.; Inohara, T.; Saito, T.; Yoshijima, N.; Tanaka, M.; Tsuruta, H.; Yashima, F.; Shimizu, H.; Fukuda, K.; Naganuma, T.; et al. Aspirin Versus Clopidogrel as Single Antithrombotic Therapy After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: Insight from the OCEAN-TAVI Registry. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2021, 14, e010097.

- Angiolillo, D.J.; Fernandez-Ortiz, A.; Bernardo, E.; Alfonso, F.; Macaya, C.; Bass, T.A.; Costa, M.A. Variability in Individual Responsiveness to Clopidogrel: Clinical Implications, Management, and Future Perspectives. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2007, 49, 1505–1516.

- Jimenez Diaz, V.A.; Tello-Montoliu, A.; Moreno, R.; Cruz Gonzalez, I.; Baz Alonso, J.A.; Romaguera, R.; Molina Navarro, E.; Juan Salvadores, P.; Paredes Galan, E.; De Miguel Castro, A.; et al. Assessment of Platelet REACtivity After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: The REAC-TAVI Trial. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2019, 12, 22–32.

- Vavuranakis, M.A.; Kalantzis, C.; Voudris, V.; Kosmas, E.; Kalogeras, K.; Katsianos, E.; Oikonomou, E.; Siasos, G.; Aznaouridis, K.; Toutouzas, K.; et al. Comparison of Ticagrelor Versus Clopidogrel on Cerebrovascular Microembolic Events and Platelet Inhibition during Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation. Am. J. Cardiol. 2021, 154, 78–85.

- Sherwood, M.W.; Gupta, A.; Vemulapalli, S.; Li, Z.; Piccini, J.; Harrison, J.K.; Dai, D.; Vora, A.N.; Mack, M.J.; Holmes, D.R.; et al. Variation in Antithrombotic Therapy and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Preexisting Atrial Fibrillation Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: Insights from the Society of Thoracic Surgeons/American College of Cardiology Transcatheter Valve Therapy Registry. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2021, 14, e009963.

- Abdul-Jawad Altisent, O.; Durand, E.; Muñoz-García, A.J.; Nombela-Franco, L.; Cheema, A.; Kefer, J.; Gutierrez, E.; Benítez, L.M.; Amat-Santos, I.J.; Serra, V.; et al. Warfarin and Antiplatelet Therapy Versus Warfarin Alone for Treating Patients with Atrial Fibrillation Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2016, 9, 1706–1717.

- Geis, N.A.; Kiriakou, C.; Chorianopoulos, E.; Pleger, S.T.; Katus, H.A.; Bekeredjian, R. Feasibility and Safety of Vitamin K Antagonist Monotherapy in Atrial Fibrillation Patients Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation. EuroIntervention 2017, 12, 2058–2066.

- Kosmidou, I.; Liu, Y.; Alu, M.C.; Liu, M.; Madhavan, M.; Chakravarty, T.; Makkar, R.; Thourani, V.H.; Biviano, A.; Kodali, S.; et al. Antithrombotic Therapy and Cardiovascular Outcomes After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2019, 12, 1580–1589.

- Nijenhuis, V.J.; Brouwer, J.; Delewi, R.; Hermanides, R.S.; Holvoet, W.; Dubois, C.L.F.; Frambach, P.; De Bruyne, B.; van Houwelingen, G.K.; Van Der Heyden, J.A.S.; et al. Anticoagulation with or without Clopidogrel after Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Implantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1696–1707.

- Connolly, S.J.; Ezekowitz, M.D.; Yusuf, S.; Eikelboom, J.; Oldgren, J.; Parekh, A.; Pogue, J.; Reilly, P.A.; Themeles, E.; Varrone, J.; et al. Dabigatran versus Warfarin in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 361, 1139–1151.

- Patel, M.R.; Mahaffey, K.W.; Garg, J.; Pan, G.; Singer, D.E.; Hacke, W.; Breithardt, G.; Halperin, J.L.; Hankey, G.J.; Piccini, J.P.; et al. Rivaroxaban versus Warfarin in Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 883–891.

- Giugliano, R.P.; Ruff, C.T.; Braunwald, E.; Murphy, S.A.; Wiviott, S.D.; Halperin, J.L.; Waldo, A.L.; Ezekowitz, M.D.; Weitz, J.I.; Špinar, J.; et al. Edoxaban versus Warfarin in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 2093–2104.

- Granger, C.B.; Alexander, J.H.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Lopes, R.D.; Hylek, E.M.; Hanna, M.; Al-Khalidi, H.R.; Ansell, J.; Atar, D.; Avezum, A.; et al. Apixaban versus Warfarin in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 365, 981–992.

- Pan, K.-L.; Singer, D.E.; Ovbiagele, B.; Wu, Y.-L.; Ahmed, M.A.; Lee, M. Effects of Non-Vitamin K Antagonist Oral Anticoagulants Versus Warfarin in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation and Valvular Heart Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017, 6, e005835.

- Angiolillo, D.J.; Bhatt, D.L.; Cannon, C.P.; Eikelboom, J.W.; Gibson, C.M.; Goodman, S.G.; Granger, C.B.; Holmes, D.R.; Lopes, R.D.; Mehran, R.; et al. Antithrombotic Therapy in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation Treated with Oral Anticoagulation Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: A North American Perspective: 2021 Update. Circulation 2021, 143, 583–596.

- Overtchouk, P.; Guedeney, P.; Rouanet, S.; Verhoye, J.P.; Lefevre, T.; Van Belle, E.; Eltchaninoff, H.; Gilard, M.; Leprince, P.; Iung, B.; et al. Long-Term Mortality and Early Valve Dysfunction According to Anticoagulation Use: The FRANCE TAVI Registry. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 73, 13–21.

- Geis, N.A.; Kiriakou, C.; Chorianopoulos, E.; Uhlmann, L.; Katus, H.A.; Bekeredjian, R. NOAC Monotherapy in Patients with Concomitant Indications for Oral Anticoagulation Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2018, 107, 799–806.

- Kalogeras, K.; Jabbour, R.J.; Ruparelia, N.; Watson, S.; Kabir, T.; Naganuma, T.; Vavuranakis, M.; Nakamura, S.; Malik, I.S.; Mikhail, G.; et al. Comparison of Warfarin versus DOACs in Patients with Concomitant Indication for Oral Anticoagulation Undergoing TAVI; Results from the ATLAS Registry. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2020, 50, 82–89.

- Butt, J.H.; De Backer, O.; Olesen, J.B.; Gerds, T.A.; Havers-Borgersen, E.; Gislason, G.H.; Torp-Pedersen, C.; Søndergaard, L.; Køber, L.; Fosbøl, E.L. Vitamin K Antagonists vs. Direct Oral Anticoagulants after Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation in Atrial Fibrillation. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacother. 2021, 7, 11–19.

- Kawashima, H.; Watanabe, Y.; Hioki, H.; Kozuma, K.; Kataoka, A.; Nakashima, M.; Nagura, F.; Nara, Y.; Yashima, F.; Tada, N.; et al. Direct Oral Anticoagulants Versus Vitamin K Antagonists in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation After TAVR. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2020, 13, 2587–2597.

- Didier, R.; Lhermusier, T.; Auffret, V.; Eltchaninoff, H.; Le Breton, H.; Cayla, G.; Commeau, P.; Collet, J.P.; Cuisset, T.; Dumonteil, N.; et al. TAVR Patients Requiring Anticoagulation: Direct Oral Anticoagulant or Vitamin K Antagonist? JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2021, 14, 1704–1713.

- Tanawuttiwat, T.; Stebbins, A.; Marquis-Gravel, G.; Vemulapalli, S.; Kosinski, A.S.; Cheng, A. Use of Direct Oral Anticoagulant and Outcomes in Patients with Atrial Fibrillation after Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: Insights from the STS/ACC TVT Registry. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 11, e023561.

- An, Q.; Su, S.; Tu, Y.; Gao, L.; Xian, G.; Bai, Y.; Zhan, Q.; Xu, X.; Xu, D.; Zeng, Q. Efficacy and Safety of Antithrombotic Therapy with Non-Vitamin K Antagonist Oral Anticoagulants after Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 2021, 12, 20406223211056730.

- Jochheim, D.; Barbanti, M.; Capretti, G.; Stefanini, G.G.; Hapfelmeier, A.; Zadrozny, M.; Baquet, M.; Fischer, J.; Theiss, H.; Todaro, D.; et al. Oral Anticoagulant Type and Outcomes After Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2019, 12, 1566–1576.

- Dangas, G.D.; Tijssen, J.G.P.; Wöhrle, J.; Søndergaard, L.; Gilard, M.; Möllmann, H.; Makkar, R.R.; Herrmann, H.C.; Giustino, G.; Baldus, S.; et al. A Controlled Trial of Rivaroxaban after Transcatheter Aortic-Valve Replacement. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 120–129.

- Collet, J.P. Oral Anti-Xa Anticoagulation after Trans-Aortic Valve Implantation for Aortic Stenosis: The Randomized ATLANTIS Trial. In Proceedings of the ACC 21 Scientific Sessions, Virtual, 15 May 2021.