Characterize particulate matter (PM) concentrations released during the application of cosmetic powders, estimate the respiratory dosage for the different cosmetic powder types, and evaluate the sustainability based on the environmental and health effects.

- cosmetic powder

- inhalable aerosol

- sustainability

- respiratory tract

- deposition

- dosage

Dear author, the following contents are excerpts from your papers. They are editable.

(Due to the lack of relevant professional knowledge, our editors cannot complete a complete entry by summarizing your paper, so if you are interested in this work. you may need to write some contents by yourself. A good entry will better present your ideas, research and results to other scholars. Readers will also be able to access your paper directly through entries.)

1. Introduction

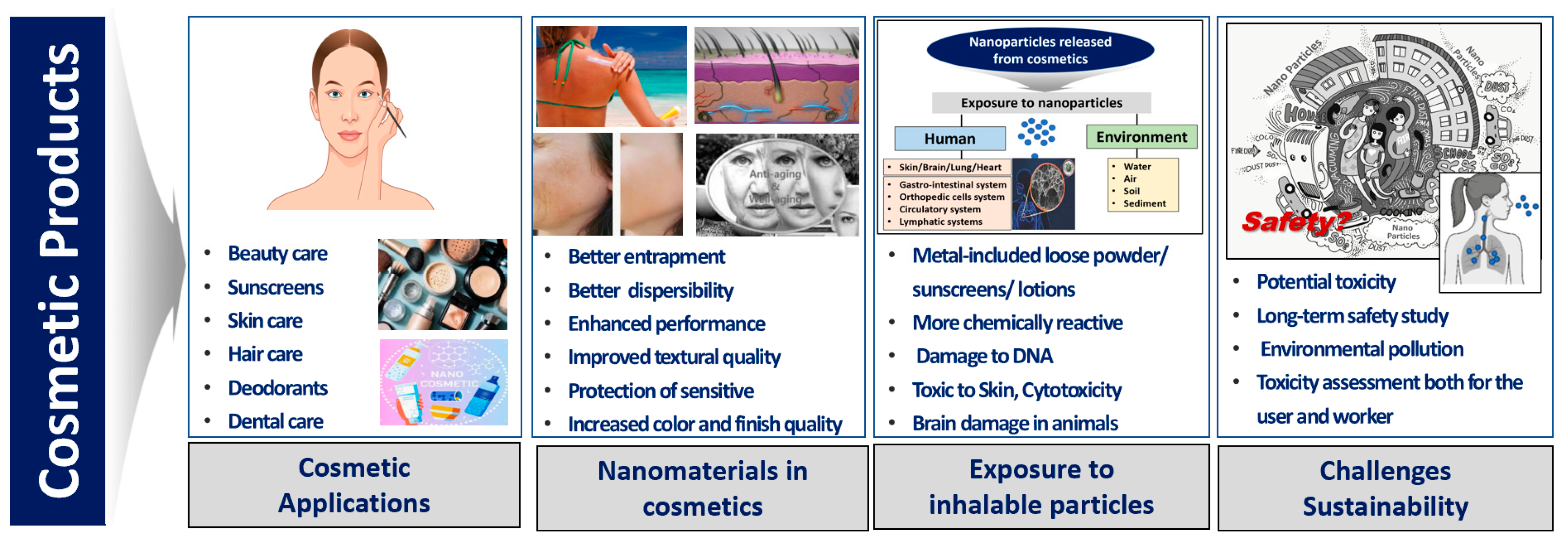

Cosmetics are attractive to consumers of various ages [1,2,3] because they enhance or change appearance without affecting the structure or function of the body [4]. According to the Environmental Working Group, women use an average of 12 products per day, containing 168 different chemicals [5,6]. Over 3000 chemicals are used to formulate a large range of fragrances used in consumer products worldwide [7]. In the United States alone, there are approximately 12,500 unique chemical ingredients approved for use in the manufacture of personal care products. The combination of active ingredients in cosmetics is essential for improving skin health in areas such as anti-aging, moisturizing, and acne treatment [8], and cosmetic manufacturers are constantly developing new products to meet the needs of users.

European Regulation (EC) No. 1223/2009 states that “cosmetics are any substance or mixture intended to come into contact with the external parts of the human body (epidermis, hair system, nails).” In particular, the EC regulations, which took effect 11 July 2013, stipulate that cosmetics found in the European market must be safe for consumer health. Some commonly used cosmetics include products that can be rinsed immediately (e.g., shampoo, toothpaste), but each type of product includes a body emulsion that can touch the skin for several hours, especially a powder or spray that can be directly exposed to the body’s respiratory system.

2. Effect of Cosmetics on Respiratory System

When using consumer products, airborne particles can be released as a respirable fraction of the health-related particle size [9,10,11]. Moreover, people may be exposed to nanosized and unsafe ingredients. For example, Zn [12,13], TiO2 [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29], SiO2 [30,31,32,33], Ag [34,35,36,37] and Au substances [38,39] were included in respirable particles, and these airborne particles could penetrate deep into the gas-exchange regions of the lungs [40,41,42,43,44,45].

Currently, nano-cosmetics are an area of particular interest because nanomaterials can be used to create new types of products. Since nanotechnology is a key driver of product innovation, it has the potential to change many parts of everyday consumer goods, especially cosmetics, and a variety of products are already on the market. However, respirable-sized particles (including nanoparticles) in cosmetics have been used as unstable particles or insoluble particles that are decomposed into molecular components [46,47,48,49,50,51], and consumers must be assured about the safety of the particles used [52]. Ingredients present in cosmetics are used as antioxidants, preservatives, emollients, surfactants, pigments, fragrances, and ultraviolet absorbers, but are strictly regulated by relevant laws in many countries [53]. In addition, some toxicity studies have tested manufactured nanomaterial products in different exposure situations to demonstrate the adverse effects of nanoparticles containing metal that can induce significant neurotoxicity, cytotoxicity, and genotoxicity in human cell cultures, which is critical for assessing the health risk to human or animal cells. However, these studies only observed a dose-dependent and time-dependent relationship at the highest dose at 24 h and 48 h post-exposure in cultured human cells and did not consider a realistic exposure approach [54,55,56,57,58,59,60].

These issues raise concerns about potential consumer exposure to penetrating particles in the lungs, including the use of cosmetics and personal care products, and, in particular, the toxic inorganic components contained within them [53]. At the same time, relatively little is known about the quantitative exposure assessment to inhalable aerosols when using cosmetics in general. In a recent study investigating the potential inhalation exposure and lung deposition resulting from the use of cosmetic powders, including nanoparticle formulations [61], it was found that particles of respirable size (< 10 µm) were released and potentially inhaled. In the case of respirable-sized cosmetics, once inhaled, these particles settle in all areas of the respiratory system from the head airways to the alveoli. To this end, it is necessary to conduct a quantitative exposure assessment of aerosols generated when using cosmetics and to investigate possible toxic substances contained in the exposed aerosols.

The respiratory exposure characteristics depend on the chemical manufacturing route, the manufacturing process, and the conflicting views of manufacturers [62]. The report “Our Common Future” highlighted the need for a sustainable way of life [63]. Since then, the world has changed dramatically socially and economically, raising consumer awareness of environmental and social issues regarding resources consumed at an unsustainable rate. Based on these issues, the main decision to purchase cosmetics still depends on personal preferences, but environmental and ethical considerations are becoming increasingly important [64].

Another factor driving the cosmetics industry to a more sustainable path is the availability of raw materials that are advantageous from a sustainability perspective [65]. Some countries in the European Union have already banned the use of microplastics in cosmetics [66]. The use of plastic microbeads has decreased by 97.6% between 2012 and 2017; 4250 tons of plastic has been replaced [67]. From another sustainability perspective, some countries mandate the labeling of environmental indicators and impose various environmental taxes such as a packaging tax or landfill tax, which affects purchasing behaviors [68].

Furthermore, the cosmetic supply chain can have an impact on sustainability, so every step in the product lifecycle must be considered from the initial design and sourcing of raw materials to manufacturing, packaging, and distribution. The term “eco-innovation” is crucially an overall assessment of the environmental impacts and risks [69], which can be a tool to support assessment within the environmental dimension of cosmetic sustainability [70] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Cosmetic applications, exposure to inhalable particles released from cosmetics and sustainability challenges of future strategies [8,51,70].