Sustainability leadership has gained much popularity as an emergent multidisciplinary area in the recent literature. Worldwide scholars call for more sustainability studies as an important leadership agenda . Modern leaders need to strategically lead their businesses beyond profit-maximization or economic performance and maneuver their vision and strategy toward environmental protection and social responsibility. The literature urges future leaders and managers to purposefully develop value-oriented sustainable leadership and sustainability competencies in their business practices as well as to balance the economic performance and socio-environmental responsibility to thrive for long-term success. The latest empirical research also indicates that sustainability leadership is a key determinant of long-term success and sustainability performance outcomes. The topic strategically becomes critical to achieve corporate resilience, longevity and sustainable futures.

- sustainability leadership

- sustainable leadership

- sustainable entrepreneurship

- social entrepreneurship

- community-based social enterprise

- social enterprise

- SME

- community-based tourism

- corporate sustainability

- sustainable development

- resilience

- SDG

1. Critical Review of the Literature

2. Sustainable Leadership Research Framework

3. The Concept of Community-Based Social Enterprise (CBSE)

4. Integration of Sustainable Leadership (SL) and Community-Based Social Enterprise (CBSE)

| Leadership Elements | SL Theoretical Framework | Relevance in the CBSE Context |

|---|---|---|

| Foundations practices | ||

| Developing people | Develops everyone continuously | Developing people is key to sustainable CBSEs. |

| Labor relation | Seeks cooperation | Sustainable CBSEs care for their staff and embed amicable labor relationships. |

| Retaining staffs | Values long tenure at all levels | CBSEs value their community members and staff. They tend to retain long-term staff for sustainable community development. |

| Succession planning | Promotes from within wherever possible | Succession planning and internal promotion is essential to develop long-term continuity and sustainable growth in CBSEs. |

| Valuing staff | Is concerned about employees’ welfare | Sustainable CBSEs value and care for the well-being and welfare of the community members and the locals. |

| CEO and top team | CEO works as top team member or speaker | Shared or participative leadership and decision-making among its top-team community committees, members and/or stakeholders are key for sustainable CBSEs. |

| Ethical behavior | “Doing the right thing” as an explicit core value | Sustainable CBSEs comply with high ethics, morals and values, extending beyond the law’s requirements. |

| Long-term or short-term perspective | Prefers the long term over the short term | Long-term orientation (e.g., long-term thinking, planning decisions and strategies) instead of the short-term goals is critical to develop sustainable impacts in CBSEs. |

| Organizational change | Change is an evolving and considered process | CBSEs are susceptible to external environmental impacts (e.g., economic, political, social and pandemic). They should adapt to systemic change to survive and thrive. |

| Financial market orientation | Seeks maximum independence from others | CBSEs should be independent from external market pressures, but financial supports from governmental or external institutional funding may be needed, depending on the varied CBSE developmental stages. |

| Responsibility for the environment | Protects the environment | Sustainable CBSEs pay respect to their environment and stay responsible for their environmental impacts. |

| Social responsibility | Values people and the community | Social and cultural sustainability in local communities are taken into account for sustainable CBSEs. |

| Stakeholder consideration | Everyone matters | Caring for stakeholders becomes a key to successful and sustainable CBSEs. |

| Vision’s role in the business | Shared view of future is an essential strategic tool | A strong and shared vision in CBSEs is a strategic management tool toward success and sustainability. |

| Higher level practices | ||

| Decision-making | Is consensual and devolved | Decision-making should be driven by community enterprise committees and teams to benefit sustainable development in successful CBSEs. |

| Self-management | Staff are mostly self-managing | In successful CBSEs, community leaders and members are likely to be self-managed and engage in community-driven governance. They commit to take responsibilities toward community development. |

| Team orientation | Teams are extensive and empowered | Strong teamwork and committed participation from community members become critical for sustainable CBSEs. |

| Culture | Fosters an enabling, widely shared culture | Shared and strong community culture and values drive longevity, resilience and long-term success in CBSEs. |

| Knowledge-sharing and retention | Spreads throughout the organization | Knowledge-sharing and management is key to sustainable community development and resilience. Regular meetings and continuous communication among community members are essential for successful CBSEs. |

| Trust | High trust through relationships and goodwill | Trust between community leaders and all stakeholders become key to successful CBSEs. Trust enhances bonding among all community members and improves social capital toward sustainability. |

| Key performance driver | ||

| Innovation | Strong, systemic, strategic innovation evident at all levels | Innovation is critical for sustainable CBSEs due to intense competition and unexpected changes. Successful CBSEs should co-design or co-create social innovation for the long-term benefits of the community development. |

| Staff engagement | Values emotionally committed staff and the resulting commitment | Successful CBSEs need to emotionally engage with their members to create a sense of place or local ownership toward sustainable enterprises. |

| Quality | Is embedded in the culture | Sustainable CBSEs should produce superior quality products and services as well as embed high quality in all things they do to enhance long-term success. |

4.1. Long-Term Perspective

4.2. People Priority

4.3. Organizational Culture

4.4. Innovation

4.5. Social and Environmental Responsibility

4.6. Ethical Behavior

5. Community-Based Social Enterprise (CBSE) in Thailand

-

Primary Level. At this level, the community enterprises produce their own goods for their own consumption on a small scale, such as consumables such as soap, shampoo and dishwashing liquid, and the produced goods can be locally sold to community members at lower prices than those of large manufacturers. This can help lessen the cost of living for people in the community.

-

Development level. Community enterprises at the development level have the capacity to develop their new market channels. Additional goods and services are primarily sold to neighboring communities and other people who visit the communities. The revenues and profits from those transactions return to their community.

-

Progressive Level. At the progressive level, community enterprises produce their goods and services for mass markets. They better understand the market mechanism and continuously expand to other external markets and the general public. Profits are used to grow their businesses for community development and sustainability.

6. Discussion & Implications

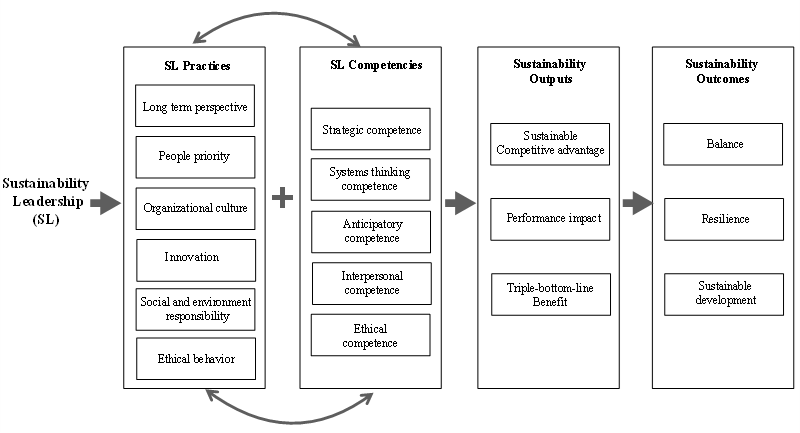

This researticlech intends to broaden the scholarly knowledge and advance the SL theoretical development. Our study The research puts forward that the sustainable leadership practices and sustainability competencies are necessary for capability building and human capital development toward sustainable futures in the CBSE context. An alternative sustainable business model for CBSE, built on the previous research of Hallinger & Suriyankietakew’s [5] sustainable leadership model and Suriyankietakew & Petison’s [6] strategic management for sustainability model, is thus proposed, as depicted in Figure 1. Figure 1 illustrates the proposed model that encapsulates the integrative development of the future of sustainability leadership via incorporating the six-category SL practices and five sustainability leadership competencies altogether to achieve overall corporate sustainability outputs and outcomes. The proposed model may unfold how the advanced SL theory connects to practice.

In practice, wthe researchers suggest that sustainability leaders, sustainable entrepreneurs and modern managers should apply the alternative sustainable business model in their business to achieve sustainable results, as depicted in Figure 1. They can pragmatically apply the essential six-category SL practices (i.e., long-term perspective, people priority, organizational culture, innovation, social and environmental responsibility and ethical behavior) together with the key competencies (i.e., strategic, system thinking, anticipatory, interpersonal and ethical competencies) to their firms. As a result, they can achieve the sustainability outputs (i.e., sustainable competitive advantage, performance impact and triple-bottom-line benefit) and gain from diverse sustainability outcomes toward future balance, resilience and sustainable development.

Further, this preseaperrch offers the following managerial suggestions. We recThe researchers recommend that modern sustainability leaders, entrepreneurs and managers in Thailand and possibly other developing countries or emerging economies should embrace and embed the essential value-based sustainable leadership practices and necessary competencies to withstand all weathers, such as the COVID-19 pandemic crisis, as well as achieve corporate sustainability and resilience, as evidenced in the case study. Here are the following how-to guidelines.

Firstly, they should adopt a long-term perspective and strategies for organization-wide management practices to achieve corporate sustainability and resilience in the long run. Secondly, they should set people as the top priority by enabling team orientation from the humanistic management and sustainable development perspective, such as sustainable HRM to HRD, with the focus on the satisfaction of all stakeholders. WThe researchers put emphasis on enabling human capital with care for stakeholders as a key to drive all-inclusive sustainable growth. Thirdly, they need to cultivate a sustaining organizational culture through strong values and a shared vision to support the ecological conservation and cultural heritage preservation that can be transferred from this generation to the next. Next, they must foster shared social innovation in conjunction with high quality and systemic knowledge-sharing or retention to support sustainable growth. This paperresearch also highlights that continuing social innovation is critical for sustainable CBSEs due to intense competition and unexpected changes in today’s environment. Additionally, successful CBSE leaders, entrepreneurs and team members should co-design or co-create social innovation for long-term sustainable benefits for the community. Fifthly, they must integrate pro-environmental behavior, social responsibility and sustainability-oriented actions to support the natural ecosystems as well as to develop lasting triple-bottom-line benefits to all stakeholders. Lastly, they need to establish strong ethical principles, moral behaviors and altruism conduct in all business decision-making and management activities to achieve sustainable results and create long-lasting sustainable enterprises. It is thus suggested that high ethical and moral values should be regularly practiced in sustainable CBSEs. Further, successful social enterprises need to go beyond the regulatory and law requirements to benefit its community growth, resilience and sustainable development.

Furthermore, outhe r studyesearch proposes that the sustainability leaders and sustainable entrepreneurs should be the change agents and become the key players in bringing about change to the business and society as a whole. Additionally, they should invest in developing the necessary competencies to create ongoing sustainability and resilience in firms. They need to purposefully and systematically build in the strategic (management) competence in their socio-environmental strategies as well as integrate sustainability criteria into business processes and all management systems to balance the triple-bottom-line benefits. They need to put emphasis on the importance of systems thinking competence, so that everyone understands how their parts are related to sustainability values and behaviors. Moreover, they can contribute accordingly to create corporate success and sustainability in the long run. They should also develop anticipatory (foresight thinking) competence to set a strong and shared long-term sustainability vision as well as be mindful of their impending actions that create impacts or forge ahead sustainable futures.

Finally, the existing sustainability challenges require sustainability leadership and strategic foresights from multi-lateral parities and diverse stakeholders to take corrective and transformative actions for sustainable growth. For policy-makers, ourthis evidence-based studyresearch may be a foundation for the further development of sustainability leadership programs (e.g., social innovation capacity-building or sustainable HR management and development) in the SME sector, particularly in the community-based social enterprises at the bottom of the pyramid settings. Our studyThe research also implies that an integrative sustainability development policy for the social enterprises is required and should be incorporated in national plans and strategies for sustainable futures. In particular, the key policy should center on systemic and strategic sustainability implementations for all-inclusive capacity-building and social human capital development. Lastly, ourthe researchers' proposed model may be an alternative sustainable business model that can guide and support balancing social-economic and ecological progression in the society toward achieving the UN SDGs or ourthe researchers' global common goals toward sustainable futures together.

References

- Brundtland, G. Unites Nations World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987.

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2015.

- Suriyankietkaew, S.; Petison, P. A retrospective and foresight: Bibliometric review of international research on strategic management for sustainability, 1991–2019. Sustainability 2019, 12, 91.

- Boiral, O.; Baron, C.; Gunnlaugson, O. Environmental leadership and consciousness development: A case study among Canadian SMEs. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 123, 363–383.

- Sachs, J.D. From millennium development goals to sustainable development goals. Lancet 2012, 379, 2206–2211.

- Haney, A.B.; Pope, J.; Arden, Z. Making it personal: Developing sustainability leaders in business. Organ. Environ. 2020, 33, 155–174.

- Lans, T.; Blok, V.; Wesselink, R. Learning apart and together: Towards an integrated competence framework for sustainable entrepreneurship in higher education. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 62, 37–47.

- Osagie, E.R.; Wesselink, R.; Blok, V.; Lans, T.; Mulder, M. Individual competencies for corporate social responsibility: A literature and practice perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 135, 233–252.

- Ploum, L.; Blok, V.; Lans, T.; Omta, O. Toward a validated competence framework for sustainable entrepreneurship. Organ. Environ. 2018, 31, 113–132.

- Dyllick, T.; Hockerts, K. Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2002, 11, 130–141.

- Gibson, K. Stakeholders and sustainability: An evolving theory. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 109, 15–25.

- Suriyankietkaew, S. Sustainable leadership and entrepreneurship for corporate sustainability in small enterprises: An empirical analysis. World Rev. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 15, 256–275.

- Suriyankietkaew, S. Effects of key leadership determinants on business sustainability in entrepreneurial enterprises. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2022. ahead-of-print.

- Maak, T.; Pless, N.M. Responsible leadership in a stakeholder society–a relational perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 66, 99–115.

- Ford, R. Stakeholder leadership: Organizational change and power. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2005, 26, 616–638.

- Parmar, B.L.; Freeman, R.E.; Harrison, J.S.; Wicks, A.C.; Purnell, L.; De Colle, S. Stakeholder theory: The state of the art. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2010, 4, 403–445.

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Creating shared value: Redefining capitalism and the role of the corporation in society. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 62–77.

- Brown, M.E.; Treviño, L.K. Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. Leadersh. Q. 2006, 17, 595–616.

- Ciulla, J.B. Ethics, the Heart of Leadership, 3rd ed.; Praeger: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 3–31.

- Resick, C.J.; Hanges, P.J.; Dickson, M.W.; Mitchelson, J.K. A cross-cultural examination of the endorsement of ethical leadership. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 63, 345–359.

- Avery, G.C.; Bergsteiner, H. Sustainable leadership practices for enhancing business resilience and performance. Stretegy Leadersh. 2011, 39, 5–15.

- Kantabutra, S.; Ractham, V.; Gerdsri, N.; Nuttavuthisit, K.; Kantamara, P.; Chiarakul, T. Sufficiency Economy Leadership Practices; Thailand Research Fund: Bangkok, Thailand, 2010.

- Suriyankietkaew, S.; Kantamara, P. Business ethics and spirituality for corporate sustainability: A Buddhism perspective. J. Manag. Spiritual. Relig. 2019, 16, 264–289.

- Avery, G.C.; Bergsteiner, H. Honeybees and Locusts: The Business Case for Sustainable Leadership; Allen & Unwin: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2010.

- Avery, G.C.; Bergsteiner, H. How BMW successfully practices sustainable leadership principles. Strategy Leadersh. 2011, 39, 11–18.

- Suriyankietkaew, S.; Avery, G. Sustainable leadership practices driving financial performance: Empirical evidence from Thai SMEs. Sustainability 2016, 8, 327.

- Suriyankietkaew, S. Effects of sustainable leadership on customer satisfaction: Evidence from Thailand. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2016, 8, 245–259.

- Hallinger, P.; Suriyankietkaew, S. Science mapping of the knowledge base on sustainable leadership, 1990–2018. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4846.

- Lourenço, I.C.; Callen, J.L.; Branco, M.C.; Curto, J.D. The value relevance of reputation for sustainability leadership. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 119, 17–28.

- Ferdig, M.A. Sustainability leadership: Co-creating a sustainable future. J. Chang. Manag. 2007, 7, 25–35.

- Galpin, T.; Whittington, J.L. Sustainability leadership: From strategy to results. J. Bus. Strategy 2012, 33, 40–48.

- Robinson, M.; Kleffner, A.; Bertels, S. Signaling sustainability leadership: Empirical evidence of the value of DJSI membership. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 101, 493–505.

- Hargreaves, A.; Fink, D. Energizing leadership for sustainability. Dev. Sustain. Leadersh. 2007, 1, 46–64.

- Avery, G.C. Leadership for Sustainable Futures: Achieving Success in a Competitive World; Edward: Cheltenham, UK, 2005.

- Day, C.; Schmidt, M. Sustaining resilience. In Developing Sustainable Leadership; Davies, B., Ed.; Paul Chapman: London, UK, 2007; pp. 65–86.

- Suriyankietkaew, S. Taking the long view on resilience and sustainability with 5Cs at B. Grimm. Glob. Bus. Organ. Excell. 2019, 38, 11–17.

- Suriyankietkaew, S.; Avery, G.C. Leadership practices influencing stakeholder satisfaction in Thai SMEs. Asia Pac. J. Bus. Admin. 2014, 6, 247–261.

- McCauley, C.D.; McCall Jr, M.W. Using Experience to Develop Leadership Talent: How Organizations Leverage On-The-Job Development; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014.

- Quinn, L.; D’amato, A. Globally responsible leadership a leading edge conversation. In CCL White Paper; Center for Creative Leadership: Greensboro, NC, USA, 2008.

- Visser, W.; Courtice, P. Sustainability Leadership: Linking Theory and Practice; Social Sciencew Research Network: Rochester, NY, USA, 2011.

- Gordon, J.C.; Berry, J.K. Environmental leadership leadership equals essential leadership. In Environmental Leadership Equals Essential Leadership; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2008.

- Albert, M. The Rhine model of capitalism: An investigation. Eur. Bus. J. 1992, 4, 8–22.

- Kantabutra, S.; Avery, G.C. Sustainable leadership at Siam Cement Group. J. Bus. Strategy 2011, 32, 32–41.

- Kantabutra, S.; Avery, G. Sustainable leadership: Honeybee practices at a leading Asian industrial conglomerate. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2013, 5, 36–56.

- Kantabutra, S.; Suriyankietkaew, S. Sustainable leadership: Rhineland practices at a Thai small enterprise. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2013, 19, 77–94.

- Robinson, J.; Mair, J.; Hockerts, K. (Eds.) International Perspectives on Social Entrepreneurship; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2009.

- Ivenger, A. Role of Social Enterorise Greenhoiuse in Providence’s Economics Development. In Social Enterprise Greenhouse Talent Retention Intern; Providence: Granite Bay, CA, USA, 2015.

- Cornelius, N.; Todres, M.; Janjuha-Jivraj, S.; Woods, A.; Wallace, J. Corporate social responsibility and the social enterprise. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 81, 355–370.

- Pearce, J.; Kay, A. Social Enterprise in Anytown; Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation: London, UK, 2003.

- Bailey, N. The role, organisation and contribution of community enterprise to urban regeneration policy in the UK. Prog. Plan. 2012, 77, 1–35.

- Peredo, A.M.; Chrisman, J.J. Toward a theory of community-based enterprise. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 309–328.

- Somerville, P.; McElwee, G. Situating community enterprise: A theoretical exploration. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2011, 23, 317–330.

- Kleinhans, R. False promises of co-production in neighbourhood regeneration: The case of Dutch community enterprises. Public Manag. Rev. 2017, 19, 1500–1518.

- Tracey, P.; Phillips, N.; Haugh, H. Beyond philanthropy: Community enterprise as a basis for corporate citizenship. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 58, 327–344.

- Haugh, H. Community–led social venture creation. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2007, 31, 161–182.

- Munoz, S.-A.; Steiner, A.; Farmer, J. Processes of community-led social enterprise development: Learning from the rural context. Community Dev. J. 2015, 50, 478–493.

- Chotithammaporn, W.; Sannok, R.; Mekhum, W.; Rungsrisawat, S.; Poonpetpun, P.; Wongleedee, K. The development of physical distribution center in marketing for small and micro community enterprise (SMCE) product in Bangkontee, Samut Songkram. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 207, 121–124.

- Sriviboon, C. Business Performance Of Small And Micro Community Enterprise In Agricultural Products For Developing The Commercial Quality. Multicult. Educ. 2021, 7, 318–326.

- Bailey, N.; Kleinhans, R.; Lindbergh, J. An Assessment of Community-Based Social Enterprise in Three European Countries; Power to Change, University of Wesminter: London, UK, 2018.

- Anderson, R.; Honig, B.; Peredo, A. Communities in the global economy: Where social and indigenous entrepreneurship meet. In Entrepreneurship as Social Change: A Third New Movements in Entrepreneurship Book; Chris, S., Daniel, H., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2006; pp. 56–78.

- Gibbons, J.; Hazy, J.K. Leading a large-scale distributed social Enterprise: How the leadership culture at goodwill industries creates and distributes value in communities. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 2017, 27, 299–316.

- Boyer, D.; Creech, H.; Paas, L. Report for SEED Initiative Research Programme: Critical Success Factors and Performance Measures for Start-Up Social and Environmental Enterprises; International Institute for Sustainable Development: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2008.

- Cieslik, K. Moral economy meets social enterprise community-based green energy project in rural Burundi. World Dev. 2016, 83, 12–26.

- Minkler, M.; Blackwell, A.G.; Thompson, M.; Tamir, H. Community-based participatory research: Implications for public health funding. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 1210–1213.

- Thompson, J.L. Social enterprise and social entrepreneurship: Where have we reached? A summary of issues and discussion points. Soc. Enterp. J. 2008, 4, 149–161.

- Wallace, B. Exploring the meaning (s) of sustainability for community-based social entrepreneurs. Soc. Enterp. J. 2005, 1, 78–89.

- Rowlands, J.; Knox, M.W.; Campbell, T.; Cui, A.; DeJesus, L. Leadership in tourism: Authentic leaders as facilitators of sustainable development in Tasmanian tourism. In Research Anthology on Business Continuity and Navigating Times of Crisis; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 1643–1663.

- Stiglitz, J.E. Risk and global economic architecture: Why full financial integration may be undesirable. Am. Econ. Rev. 2010, 100, 388–392.

- Hofstede, G.; Minkov, M. Long-versus short-term orientation: New perspectives. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2010, 16, 493–504.

- Albert, I.O. Introduction to Third-Party Intervention in Community Conflicts; John Archers: Ibadan, Nigeria, 2001.

- Kantabutra, S. Achieving corporate sustainability: Toward a practical theory. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4155.

- Mitchell, L. Corporate Irresponsibility: America’s Newest Export; Yale University Press: New Havebn, CT, USA, 2001.

- Eccles, R.G.; Ioannou, I.; Serafeim, G. The Impact of a Corporate Culture of Sustainability on Corporate Behavior and Performance; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, CA, USA, 2012.

- Kramar, R. Beyond strategic human resource management: Is sustainable human resource management the next approach? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 1069–1089.

- Collins, J.C.; Porras, J.I. Building your company’s vision. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1996, 74, 65–77.

- Baum, J.R.; Locke, E.A.; Kirkpatrick, S.A. A longitudinal study of the relation of vision and vision communication to venture growth in entrepreneurial firms. J. Appl. Psychol. 1998, 83, 43–54.

- Kantabutra, S. Toward an organizational theory of sustainability vision. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1125.

- Tuna, M.; Ghazzawi, I.; Tuna, A.A.; Catir, O. Transformational leadership and organizational commitment: The case of Turkey’s hospitality industry. SAM Adv. Manag. J. 2011, 76, 10–25.

- Hamel, G.; Breen, B. Building an innovation democracy: WL Gore. In The Future of Management; Harvard Business Publishing: Brighton, MA, USA, 2007.

- Çakar, N.D.; Ertürk, A. Comparing innovation capability of small and medium-sized enterprises: Examining the effects of organizational culture and empowerment. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2010, 48, 325–359.

- Martinez-Conesa, I.; Soto-Acosta, P.; Palacios-Manzano, M. Corporate social responsibility and its effect on innovation and firm performance: An empirical research in SMEs. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 2374–2383.

- Parida, V.; Westerberg, M.; Frishammar, J. Inbound open innovation activities in high-tech SMEs: The impact on innovation performance. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2012, 50, 283–309.

- Ludvig, A.; Wilding, M.; Thorogood, A.; Weiss, G. Social innovation in the Welsh Woodlands: Community based forestry as collective third-sector engagement. For. Policy Econ. 2018, 95, 18–25.

- Ravazzoli, E.; Dalla Torre, C.; Da Re, R.; Govigli, V.M.; Secco, L.; Górriz-Mifsud, E.; Pisani, E.; Barlagne, C.; Baselice, A.; Bengoumi, M.; et al. Can social innovation make a change in European and Mediterranean marginalized areas? Social innovation impact assessment in agriculture, fisheries, forestry, and rural development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1823.

- Sanusi, N.A.; Kusairi, S.; Mohamad, M.F. The Conceptual Framework of Social Innovation in Social Enterprise. J. Innov. Bus. Econ. 2017, 1, 41–48.

- Sinclair, S.; Baglioni, S. Social innovation and social policy–promises and risks. Soc. Policy Soc. 2014, 13, 469–476.

- Mosedale, J.; Voll, F. Social innovations in tourism: Social practices contributing to social development. In Social Entrepreneurship and Tourism; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; pp. 101–115.

- Leadbeater, C. The socially entrepreneurial city. In Social Entrepreneurship: New Models of Sustainable Social Change; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 233–246.

- Kautonen, T.; Schillebeeckx, S.J.; Gartner, J.; Hakala, H.; Salmela-Aro, K.; Snellman, K. The dark side of sustainability orientation for SME performance. J. Bus. Ventur. Insights 2020, 14, e00198.

- Sáez-Martínez, F.J.; Díaz-García, C.; González-Moreno, Á. Factors promoting environmental responsibility in European SMEs: The effect on performance. Sustainability 2016, 8, 898.

- Khan, S.A.R.; Sharif, A.; Golpîra, H.; Kumar, A. A green ideology in Asian emerging economies: From environmental policy and sustainable development. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 27, 1063–1075.

- Khan, S.A.R.; Razzaq, A.; Yu, Z.; Miller, S. Industry 4.0 and circular economy practices: A new era business strategies for environmental sustainability. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 4001–4014.

- Kemavuthanon, S.; Duberley, J. A Buddhist view of leadership: The case of the OTOP project. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2009, 30, 737–758.

- Wang, L.C.; Calvano, L. Is business ethics education effective? An analysis of gender, personal ethical perspectives, and moral judgment. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 126, 591–602.

- Derr, C.L. Ethics and leadership. J. Leadersh. Account. Ethics 2012, 9, 66–71.

- Groves, K.S.; LaRocca, M.A. An empirical study of leader ethical values, transformational and transactional leadership, and follower attitudes toward corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 103, 511–528.

- Karim, K.; Suh, S.; Tang, J. Do ethical firms create value? Soc. Responsib. J. 2016, 12, 54–68.

- Eisenbeiss, S.A.; Van Knippenberg, D.; Fahrbach, C.M. Doing well by doing good? Analyzing the relationship between CEO ethical leadership and firm performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 128, 635–651.

- Kitsios, F.; Kamariotou, M.; Talias, M.A. Corporate sustainability strategies and decision support methods: A bibliometric analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 521.

- Sekerka, L.E.; Stimel, D. Environmental sustainability decision-making: Clearing a path to change. J. Public Aff. 2012, 12, 195–205.

- Doherty, B.; Kittipanya-Ngam, P. The emergence and contested growth of social enterprise in Thailand. J. Asian Public Policy 2021, 14, 251–271.

- Nuchpiam, P.; Punyakumpol, C. Social enterprise landscape in Thailand. In Social Enterprise in Asia: Theory, Models, and Practice; Talylor Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2019; pp. 137–155.

- SE Thailand. The Social Enterprise Association Thailand. Available online: https://www.sethailand.org/en/about-en/ (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Rojphongkasem, S. The State of Social Enterprise in Thailand, Social Enterprise UK. Available online: https://www.socialenterprise.org.uk/blogs/the-state-of-social-enterprise-in-thailand/ (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Office of Social Enterprise Promotion. Social Enterprise Statistics. Available online: https://www.osep.or.th/en/สถิติวิสาหกิจเพื่อสังค-2/ (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- National Village and Urban Community Fund, Prine Minister Office. Village Fund. Available online: http://www.villagefund.or.th/uploads/project_news/project_news_5dd773fe3cefc.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Community Development Department, Ministry of Interior. Pracharat Rak Samakki. Available online: https://www.cdd.go.th/ประชารัฐรักสามัคคี (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Department of Agriculture Extension. Community Enterprise Statistics 2022. Available online: http://www.sceb.doae.go.th/regis.html (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Promsaka Na Sakolnakorn, T.; Sungkharat, U. Development Guidelines for Small and Micro Community Enterprises in Songkhla Lake Basin; Department of Educational Foundation, Faculty of Liberal Arts Prince of Songkla University: Pattani, Thailand, 2013. (In Thai)

- Naipinit, A.; Sakolnakorn, T.P.N.; Kroeksakul, P. Strategic management of community enterprises in the upper northeast region of Thailand. J. Enterprising Communities People Places Glob. Econ. 2016, 10, 346–362.

- Hanwiwat, W. Problems and Obstacles in Conducting the Account of Local Enterprises in Nakhon Si Thammarat Province; Rajamangala University of Technology: Pathum Thani, Thailand, 2011.

- Ruengdet, K.; Wongsurawat, W. Characteristics of successful small and micro community enterprises in rural Thailand. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 2010, 16, 385–397.

- Chandhasa, R. The Community-Enterprise Trademark and Packaging Design in Ban Dung District in Udonthani, Thailand. Asian Soc. Sci. 2017, 13, 59–70.

- Saengthong, P. The guideline for marketing improvement of the community enterprise: The case study of Mae Ban Kasettakorn’s Kohyorhand-woven fabric, Tambon Kohyor, Mueang District, Songkhla Province. SKRU Acad. J. 2010, 3, 1–6.

- Sakolnakorn, T.P.N. The Analysis Of Problem And Threat Of Small And Medium-Sized Enterprizes In Northeast Thailand. Int. Bus. Econ. Res. J. (IBER) 2010, 9, 123–132.