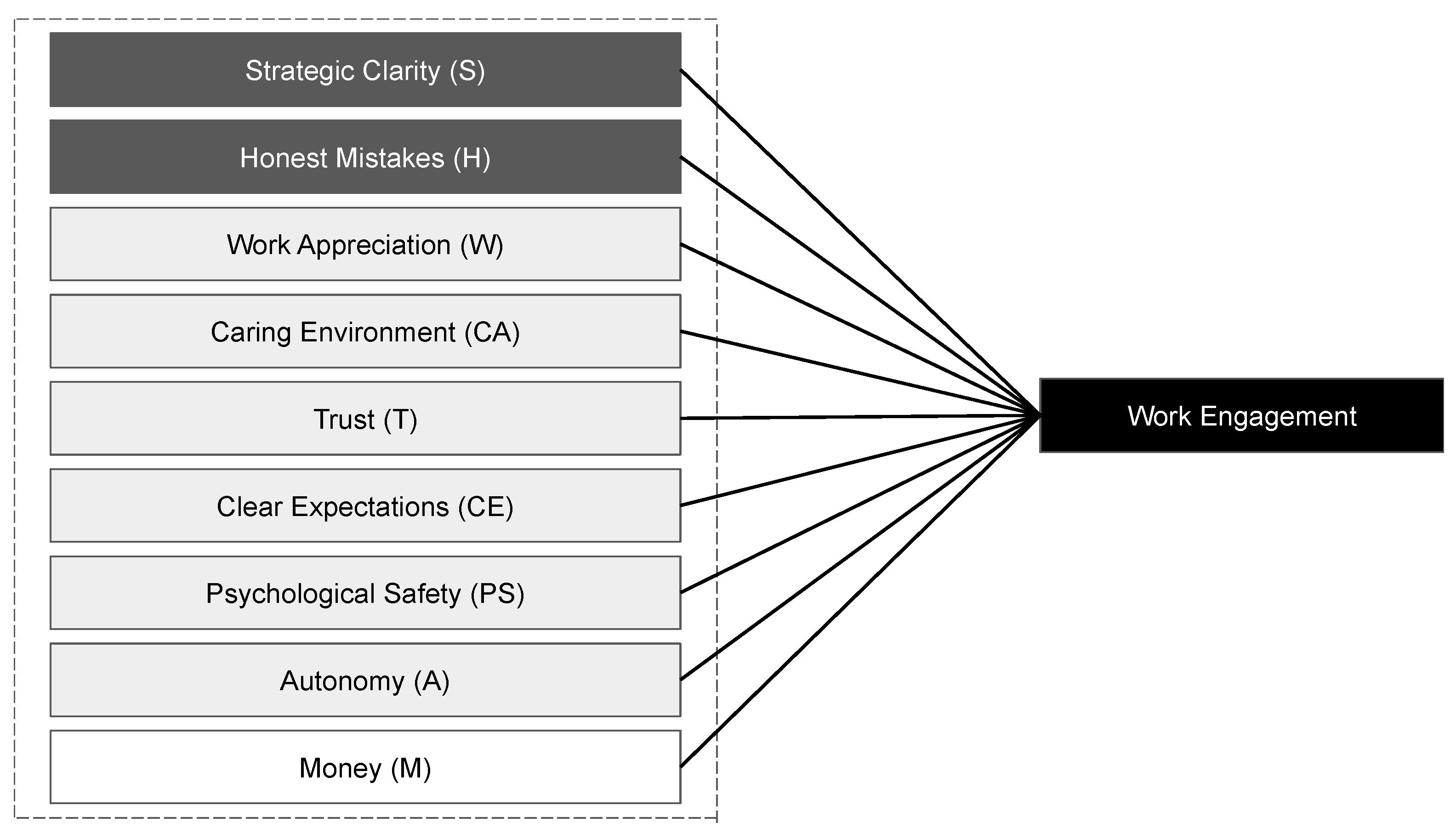

Multiple studies highlight the link between engagement at work and performance, influencing organizations to put more effort into improving employee engagement levels. High levels of engagement at work (e.g., Work Engagement or WE) in the public sector directly impact the health, education, and economic services obtained by the population. RThe influence of multiple psychological parameters on employees’ work engagement (WE) within thesearchers' public sector are examined. The idea is to break the concept of WE down into eight individually measurable parameters: strategic clarity, honest mistakes, work appreciation, a caring environment, trust, clear expectations, psychological safety, and autonomy. Honest mistakes refers to how mistakes are perceived within an organization and is an Important predictor for work engagement that will allow for a better understanding and development of stronger interventions.

- honest mistakes

- public sector management

- work engagement

- future of work

- remote work

- mistakes

1. Introduction

2. Predictors for Work Engagement and Honest Mistakes

Commonly, work engagement (WE) is defined as “a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption” [23]. WE is most often measured by the Utrecht WE index [24][25][26] alongside other scales [27][28][29][30][31]. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) adopted the Utrecht index to measure levels of WE in the public sector [32]. The adapted WE index has high validity and reliability. Nonetheless, this index does not help break down the social and psychological parameters that influence the WE in practice and simply provides an overview. Looking beyond the index, toward a more nuanced view of WE, would allow for the development of stronger interventions. Namely, the main contribution of this research is the breakdown of the WE into individually measurable parameters, providing a better understanding of the sociological and work environmental mechanisms that are taking part in defining the level of WE of employees. The literature on WE and motivation has distinguished multiple mechanisms that have been shown to influence it empirically. Based on this literature of mechanisms and dependencies, researchers define eight parameters that show strong connections to WE across several cultures, sectors, and times: namely, strategic clarity, honest mistakes, work appreciation, a caring environment, trust, clear expectations, psychological safety, and autonomy. Researchers also include monetary compensation in researchers' analyses to be consistent with recent research. A schematic view of these parameters is provided in Figure 1, and a summary of these properties is provided in Table 1. Further descriptions of these parameters are found in the following paragraphs.

| Name | Description |

|---|---|

| Strategic clarity | Feeling of purpose in one’s work, alignment to company vision. |

| Honest mistakes | Perceived ability to make mistakes and learn/grow from them without facing significant repercussions. |

| Work appreciation | Continuous perception of organizational appreciation for one’s individual contribution. |

| Caring environment | Willingness of coworkers to reciprocate care and consideration in social exchanges. |

| Trust | Trust in how one’s organization and/or its leaders will behave in the future and transparency of policies and processes. |

| Clear expectations | Well-defined objectives and goals combined with well-given feedback. |

| Psychological safety | The absence of psychological and social risk or harm within a team, safety and support in taking risks. |

| Autonomy | Ability to exercise one’s independent judgment at work, control over decisions within one’s job. |

| Money | Absolute value of monetary compensation given to the employee as a result of the work, salary or in-kind compensation. |

References

- Al-Tkhayneh, K.; Kot, S.; Shestak, V. Motivation and demotivation factors affecting productivity in public sector. Adm. Manag. Public 2019, 33, 77–102.

- Bovaird, T. Beyond Engagement and Participation: User and Community Coproduction of Public Services. Public Adm. Rev. 2007, 67, 846–860.

- Vigoda-Gadot, E.; Eldor, L.; Schohat, L. Engage Them to Public Service: Conceptualization and Empirical Examination of Employee Engagement in Public Administration. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2017, 43, 518–538. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/12317990/Engage_Them_to_Public_Service_Conceptualization_and_Empirical_Examination_of_Employee_Engagement_in_Public_Administration (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Jin, M.H.; McDonald, B. Understanding Employee Engagement in the Public Sector: The Role of Immediate Supervisor, Perceived Organizational Support, and Learning Opportunities. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2017, 47, 881–897.

- Hayes, M.; Chumney, F.; Wright, C.; Buckingham, M. The Global Study of Engagement—Technical Report; ADP Research Institute: Roseland, NJ, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.adp.com/-/media/adp/resourcehub/pdf/adpri/adpri0102_2018_engagement_study_technical_report_release%20ready.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Hayes, M.; Buckingham, M. The Global Study of Engagement—Technical Report; ADP Research Institute: Roseland, NJ, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.google.com.hk/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwiE2PmWsJ_4AhW1tlYBHadXDOMQFnoECA0QAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.ufic.ufl.edu%2FDocuments%2FAnnualReport201920.pdf&usg=AOvVaw1Gw1ApVoGJcY8rTANSM6bI (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Assis, L.O.M.D. Compreendendo as Variações e os Determinantes Do Engajamento E Motivação Para o Trabalho de Servidores Públicos. Repositorio UNAN. 2019. Available online: https://bibliotecadigital.fgv.br/dspace/handle/10438/27716 (accessed on 15 April 2022). (In Portuguese).

- Vigoda-Gadot, E.; Eldor, L.; Schohat, L.M. Engage Them to Public Service: Conceptualization and Empirical Examination of Employee Engagement in Public Administration. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2013, 43, 518–538. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258126454_Engage_Them_to_Public_Service_Conceptualization_and_Empirical_Examination_of_Employee_Engagement_in_Public_Administration (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Reis de Souza Camões, M.; Oliveira Gomes, A. Engajamento no Trabalho: Conceitos, Teorias e Agenda de Pesquisa para o Setor Público. Adm. Pública Gestão Soc. 2021, 3. (In Portuguese)

- Dodge, T.; D’Analeze, G. Employee Engagement Task Force “Nailing the Evidence” Workgroup; Bruce Rayton University of Bath School of Management, Marks and Spencer Plc: London, UK, 2012.

- Hanaysha, J. Improving employee productivity through work engagement: Empirical evidence from higher education sector. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2016, 6, 61–70.

- Stairs, S.; Galpin, M. Positive Engagement: From Employee Engagement to Workplace Happiness. In Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology and Work; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009.

- Truss, C.; Shantz, A.; Soane, E.; Alfes, K.; Delbridge, R. Employee engagement, organisational performance and individual well-being: Exploring the evidence, developing the theory. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 2657–2669.

- Jeve, Y.B.; Oppenheimer, C.; Konje, J. Employee engagement within the NHS: A cross-sectional study. Public Adm. Rev. 2015, 4, 85–90.

- Maroni, E. Productivity in the Dutch Public Sector: The Case of Libraries and Fire Services; CBS: New York, NY, USA, 2021.

- Anthony-McMann, P.E.; Ellinger, A.D.; Astakhova, M.; Halbesleben, J.R.B. Exploring Different Operationalizations of Employee Engagement and Their Relationships with Workplace Stress and Burnout. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2017, 28, 163–195.

- Whiteoak, J.W.; Mohamed, S. Employee engagement, boredom and frontline construction workers feeling safe in their workplace. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2016, 93, 291–298.

- Bellon, J.S.; Estevez-Cubilete, A.; Rodriguez, N.; Dandy, R.; Lane, S.; Deringer, E. Employee Engagement and Customer Satisfaction. Allied Acad. Int. Conf. 2010, 7, 1–5.

- Leijten, F.R.M.; van den Heuvel, S.G.; van der Beek, A.J.; Ybema, J.F.; Robroek, S.J.W.; Burdorf, A. Associations of Work-Related Factors and Work Engagement with Mental and Physical Health: A 1-Year Follow-up Study Among Older Workers. J. Occup. Rehabil. 2015, 25, 86–95.

- Kashyap, V.; Chaudhary, R. Linking Employer Brand Image and Work Engagement: Modelling Organizational Identification and Trust in Organization as Mediators. South Asian J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2019, 6, 177–201.

- Rothmann, S.; Jorgensen, L.I.; Hill, C. Coping and work engagement in selected South African organisations. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2011, 37, 1–11.

- Soelton, M.; Amaelia, P.; Prasetyo, H. Dealing with Job Insecurity, Work Stress, and Family Conflict of Employees. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Management, Economics and Business, Berlin, Germany, 15 December 2020.

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Defining and measuring work engagement: Bringing clarity to the concept. In Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research; Psychology Press: Hove, England, 2010; pp. 10–24.

- Schaufeli, W.; Bakker, A. UWES—Utrecht Work Engagement Scale—Preliminary Manual, Version 1.1; Occupational Health Psychology Unit, Utrecht University: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2004.

- Seppala, P.; Mauno, S.; Feldt, T.; Hakanen, J.; Kinnunen, U.; Tolvanen, A. ando Schaufeli, W. The Construct Validity of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale: Multisample and Longitudinal Evidence; Springer Science+Business Media B.V.: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008.

- Schaufeli, W.B. General Engagement: Conceptualization and Measurement with the Utrecht General Engagement Scale (UGES). J. Well-Being Assess. 2017, 1, 9–24.

- Costa, P.L.; Passos, A.M.; Bakker, A.B. Team work engagement: A model of emergence. J. Occup. Organ. Phychol. 2014, 87.

- Petrovic, I.B.; Vukelic, M.; Cizmic, S. Work Engagement in Serbia: Psychometric Properties of the Serbian Version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES). Front. Phychol. 2017, 8, 1799.

- Selander, K. Work Engagement in the Third Sector. VOLUNTAS Int. J. Volunt. Nonprofit Organ. 2015, 26, 1391–1411.

- Shimazu, A.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Kosugi, S.; Suzuki, A.; Nashiwa, H.; Kato, A.; Sakamoto, A.; Irimajiri, H.; Amano, S.; Hirohata, K.; et al. Work Engagement in Japan: Validation of the Japanese Version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 57, 510–523.

- Brake, H.T.; Bouman, A.M.; Gorter, R.; Hoogstraten, J.; Eijkman, M. Professional burnout and work engagement among dentists. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2007, 115, 180–185.

- Flecha, N. Towards a Standard Questionnaire Module on Employee Engagement for Civil Service Surveys; Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development: Paris, France, 2019.

- Martela, F.; Pessi, A.B. Significant work is about self-realization and broader purpose: Defining the key dimensions of meaningful work. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 363.

- Tummers, L.G.; Knies, E. Leadership and Meaningful Work in the Public Sector. Public Adm. Rev. 2013, 73, 859–868.

- Lysova, E.I.; Allan, B.A.; Dik, B.J.; Duffy, R.D.; Steger, M.F. Fostering meaningful work in organizations: A multi-level review and integration. J. Vocat. Behav. 2019, 110, 374–389.

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. On Corporate Social Responsibility, Sensemaking, and the Search for Meaningfulness Through Work. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 1057–1086.

- Khan, M.Y. Mission Motivation and Public Sector Performance: Experimental Evidence from Pakistan. 2020. Available online: http://d-scholarship.pitt.edu/42938/ (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Edmondson, A.C. Learning from failure in health care: Frequent opportunities, pervasive barriers. Qual Saf Health Care 2004, 13 (Suppl. 2), ii3–ii9.

- Prins, J.T.; van der Heijden, F.M.M.A.; Hoekstra-Weebers, J.E.H.M.; Bakker, A.B.; van de Wiel, H.B.M. Burnout, engagement and resident physicians’ self-reported errors. Psychol. Health Med. 2009, 14, 654–666.

- Edmondson, A. Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Adm. Sci. Q. 1999, 44, 350–383.

- Schulz, K. Being Wrong: Adventures in the Margin of Error; Portobello Books Ltd.: London, UK, 2010.

- Kucharska, W. Do mistakes acceptance foster innovation? Polish and US cross-country study of tacit knowledge sharing in IT. J. Knowl. Manag. 2021, 25, 105–128.

- Domínguez-Escrig, E.; Broch, M.F.F.; Gómez, C.R.; Alcamí, L.R. Improving performance through leaders’ forgiveness: The mediating role of radical innovation. Pers. Rev. 2022, 51, 4–20.

- Cannon, M.; Edmondson, A. Failing to Learn and Learning to Fail (Intelligently). Long Range Plan. 2005, 38, 299–319.

- Ferretti, E.; Rohde, K.; Moore, G.; Daboval, T. Catch the moment: The power of turning mistakes into ‘precious’ learning opportunities. Paediatr. Child Health (Canada) 2019, 24, 156–159.

- Xing, L.; Sun, J.; Jepsen, D. Feeling shame in the workplace: Examining negative feedback as an antecedent and performance and well-being as consequences. J. Organ. Behav. 2021, 42, 1244–1260.

- Dunn, J.R.; Schweitzer, M.E. Feeling and believing: The influence of emotion on trust. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 88, 736.

- Schwarz, N.; Clore, G.L. Mood, misattribution, and judgments of well-being: Informative and directive functions of affective states. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 45, 513.

- Fredrickson, B.L. The Role of Positive Emotions in Positive Psychology the Broaden-and-Build Theory of Positive Emotions; American Psychological Association, Inc.: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; Volume 56.

- Bardi, A.; Schwartz, S.H. Values and Behavior: Strength and Structure of Relations. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2003, 29, 1207–1220.

- Dirks, K.T.; Ferrin, D.L. Trust in leadership: Meta-analytic findings and implications for research and practice. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 611–628.

- Hall, G.; Dollard, M.F.; Coward, J. Psychosocial Safety Climate: Development of the PSC-12. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2010, 17, 353.

- Dollard, M.F.; Bakker, A.B. Psychosocial safety climate as a precursor to conducive work environments, psychological health problems, and employee engagement. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2010, 83, 579–599.

- Bergmann, B.; Schaeppi, J. A data-Driven Approach to Group Creativity; Harvard Business Review: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1 May 2016; p. 124.

- Ahmad, N.; Ullah, Z.; AlDhaen, E.; Han, H.; Scholz, M. A CSR perspective to foster employee creativity in the banking sector: The role of work engagement and psychological safety. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 102968.

- Newman, A.; Donohue, R.; Eva, N. Psychological safety: A systematic review of the literature. Human resource management review. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 27, 521–535.

- Lee, H. Changes in workplace practices during the COVID-19 pandemic: The roles of emotion, psychological safety and organisation support. J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 2021, 8, 97–128.

- Zhu, Y.; Zhu, C. Management Openness and Employee Voice Behavior: An Integrated Perspective of Decision-Making Calculation and Prosocial Motivation. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Education Innovation and Economic Management, Xiamen, China, 16–17 September 2018.

- Stocker, D.; Jacobshgen, N.; Semmer, N.; Annen, H. Appreciation at Work in the Swiss Armed Forces. Swiss J. Psychol. 2010, 69, 117–124.

- Locke, E.A.; Latham, G.P. Work Motivation and Satisfaction: Light at the End of the Tunnel. Psychol. Sci. 1990, 1, 240–246.

- Rodrigues, W.A.; Reis Neto, M.T.; Gonçalves Filho, C. As influências na motivação para o trabalho em ambientes com metas e recompensas: Um estudo no setor público. Revista de Administracao Publica. Rev. Adm. Pública 2014, 48, 253–273. (In Portuguese)

- Chun, Y.H.; Rainey, H.G. Goal Ambiguity and Organizational Performance in U.S. Federal Agencies. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2005, 15, 529–557.

- Buelens, M.; Van den Broeck, H. An analysis of differences in work motivation between public and private sector organizations. Public Adm. Rev. 2007, 67, 65–74.

- Dirks, K.T.; Skarlicki, D.P. Trust in Leaders: Existing Research and Emerging Issues. Trust. Distrust Organ. Dilemmas Approaches 2004, 7, 21–40.

- Stander, E.; de Beer, L.T.; Stander, W.M. Authentic leadership as a source of optimism, trust in the organisation and work engagement in the public health care sector. SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2002, 13, 1–12.

- Madjar, N.; Ortiz-Walters, R. Trust in supervisors and trust in customers: Their independent, relative, and joint effects on employee performance and creativity. Hum. Perform. 2009, 22, 128–142.

- De La Rosa, W. Trust and Transparency of Irrational Labs. 2005. Available online: https://advanced-hindsight.com/archive/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2015/12/trust-and-transparency-why-its-important-and-how-to-build-it-with-your-users.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Zagotta, R.; Robinson, D.; Arnold, C. System for and Method of Implementing a Shared Strategic Plan of an Organization. U.S. Patent Application 09/844,259, 10 October 2002.

- Wheatley, D. Autonomy in Paid Work and Employee Subjective Well-Being. Work. Occup. 2017, 44, 296–328.

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The support of autonomy and the control behavior. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 53, 1024.

- Wheatley, D. Employee satisfaction and use of flexible working arrangements. Work Employ. Soc. 2017, 31, 567–585.

- Locke, E.A.; Latham, G.P. A Theory of Goal Setting & Task Performance; Prentice-Hall, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1990.