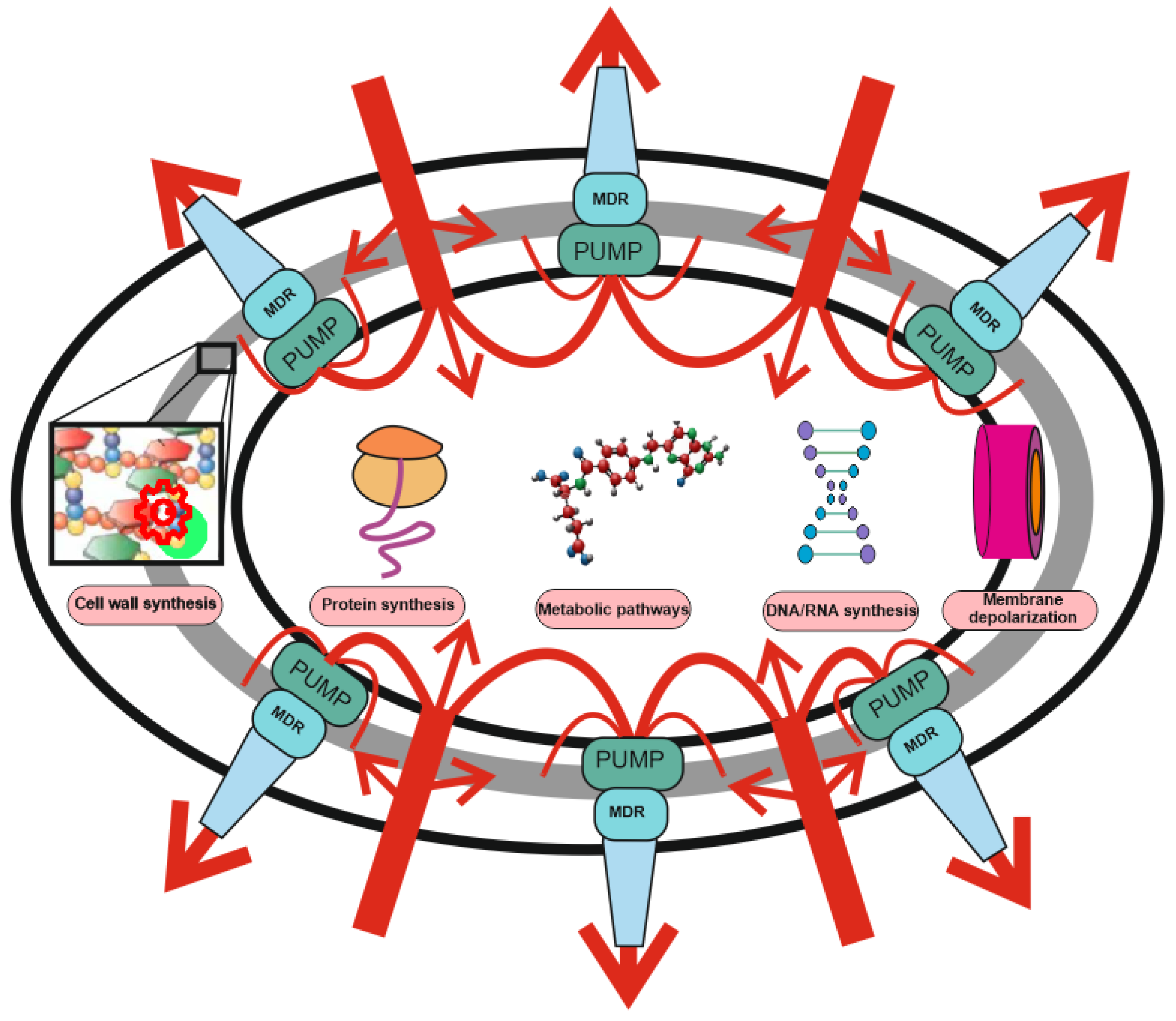

The development of new antibiotics is either very expensive or ineffective due to rapidly developing bacterial resistance. The need to develop alternative approaches to the treatment of bacterial infections, such as phage therapy, is beyond doubt. The cornerstone of bacterial defense against antibiotics are multidrug resistance (MDR) pumps, which are involved in antibiotic resistance, toxin export, biofilm, and persister cell formation. MDR pumps are the primary non-specific defense of bacteria against antibiotics, while drug target modification, drug inactivation, target switching, and target sequestration are the second, specific line of their defense. All bacteria have MDR pumps, and bacteriophages have evolved along with them and use the bacteria’s need for MDR pumps to bind and penetrate into bacterial cells.

- bacteriophage

- antibiotic

- MDR pump

- AMR resistance

1. Antibiotic Resistance: The Role of MDR Pumps

| Mechanism of Action | Antibiotic Group | Antibiotics 1 | References 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein synthesis: 30S ribosomal subunit binding |

Aminoglycosides | Kan, Sm, Gm | [54,[1055]][11] |

| Tetracyclines | Tet, Dox, Min | [53,56][9][12] | |

| Protein synthesis: 50S ribosomal subunit binding |

Streptogramins | Q/D | [57][13] |

| Macrolides | Erm, Clr, Azm | [53,58,59][9][14][15] | |

| Oxazolidinones | Tzd, Rzd | [60][16] | |

| Lincosamides | Lnm, Cdm, Prm | [61,62,63][17][18][19] | |

| Chloramphenicol | [53][9] | ||

| Nucleic Acid Synthesis | Quinolones and Fluoroquinolones |

Cip, Lvx, Nal | [56][12] |

| Metabolic Pathways | Sulfonamides | Sul, Smx | [53,64][9][20] |

| Trimethoprim | [64][20] | ||

| Depolarize Cell Membrane | Lipopeptides | Dap | [65][21] |

| Lantibiotics | Gdm | [65][21] | |

| Cell Wall Synthesis | β-Lactams | Amp | [53][9] |

| Carbapenems | Imp | [66][22] | |

| Cephalosporins | Cpx | [67][23] | |

| Monobactams | Azn | [68][24] | |

| Glycopeptides | Van | [69][25] |

2. Alternative Resistance Mechanisms Using MDR Pumps

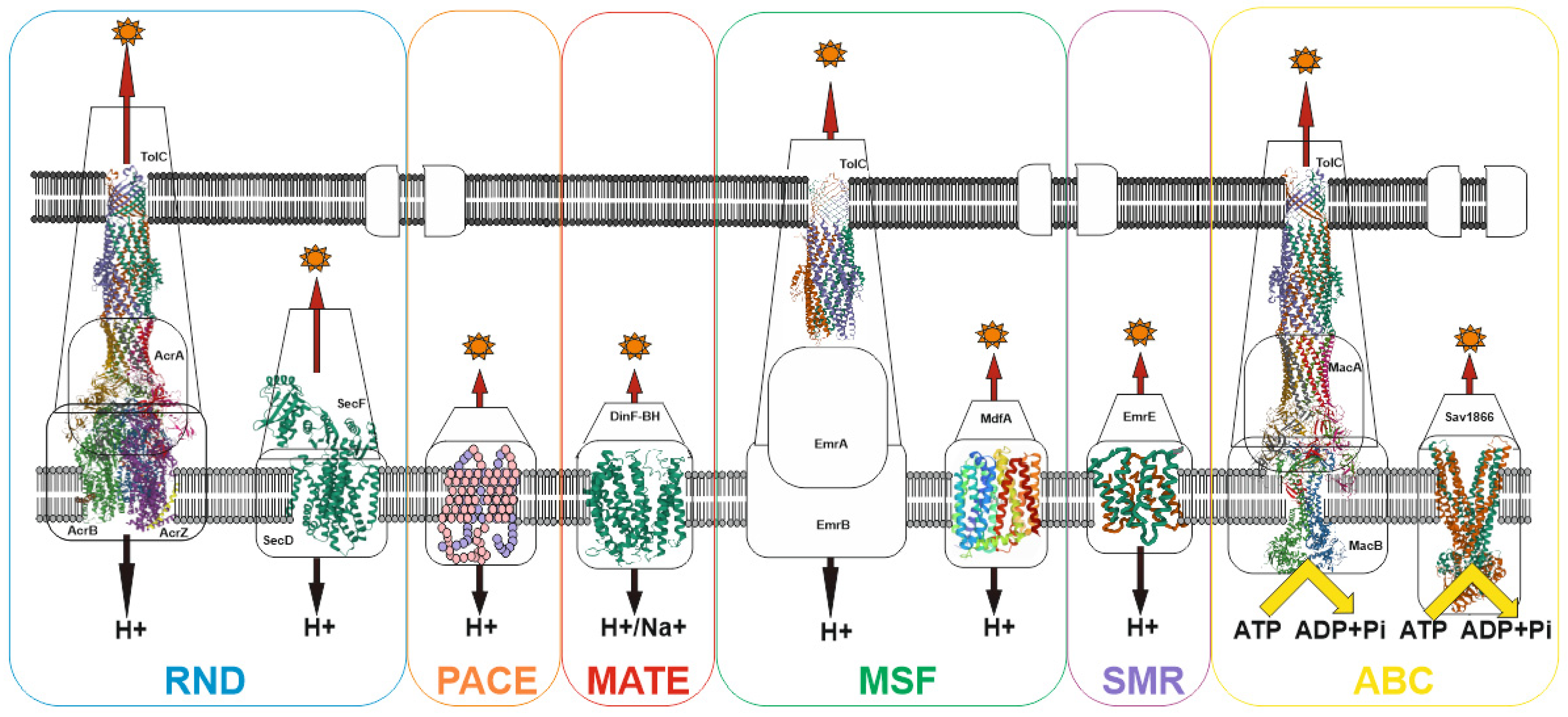

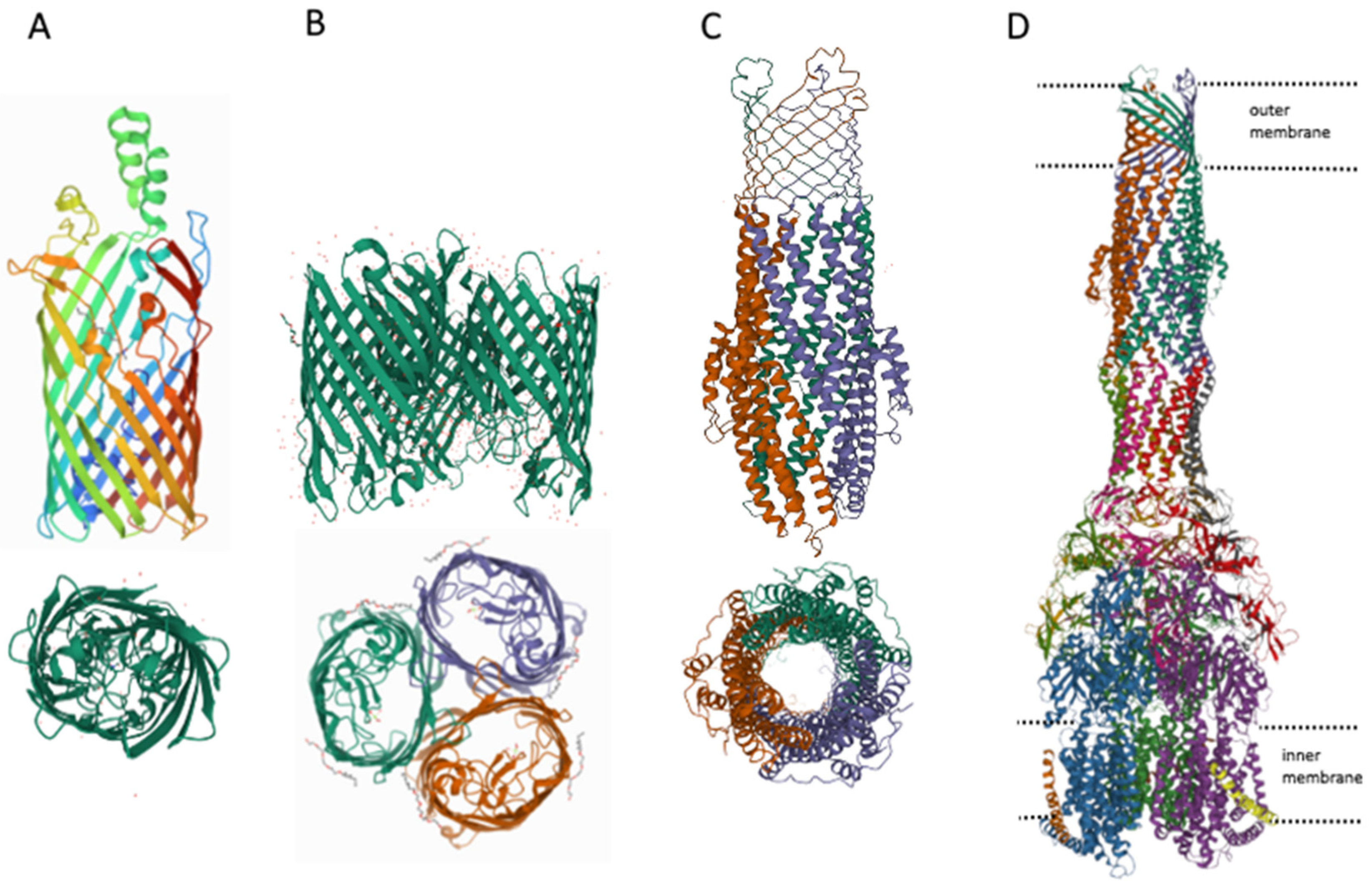

3. MDR Pumps in Bacteria

References

- Sugden, R.; Kelly, R.; Davies, S. Combatting antimicrobial resistance globally. Nat. Microbiol. 2016, 1, 16187.

- Lewis, K. The Science of Antibiotic Discovery. Cell 2020, 181, 29–45.

- Reygaert, W.C. An overview of the antimicrobial resistance mechanisms of bacteria. AIMS Microbiol. 2018, 4, 482–501.

- Anisimov, V.N.; Egorov, M.V.; Krasilshchikova, M.S.; Lyamzaev, K.G.; Manskikh, V.N.; Moshkin, M.P.; Novikov, E.A.; Popovich, I.G.; Rogovin, K.A.; Shabalina, I.G.; et al. Effects of the mitochondria-targeted antioxidant SkQ1 on lifespan of rodents. Aging 2011, 3, 1110–1119.

- Khailova, L.S.; Nazarov, P.A.; Sumbatyan, N.V.; Korshunova, G.A.; Rokitskaya, T.I.; Dedukhova, V.I.; Antonenko, Y.N.; Sku-lachev, V.P. Uncoupling and toxic action of alkyltriphenylphosphonium cations on mitochondria and the bacterium Bacillus subtilis as a function of alkyl chain length. Biochemistry 2015, 80, 1589–1597.

- Nazarov, P.A.; Osterman, I.; Tokarchuk, A.; Karakozova, M.V.; Korshunova, G.A.; Lyamzaev, K.; Skulachev, M.V.; Kotova, E.A.; Skulachev, V.; Antonenko, Y.N. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidants as highly effective antibiotics. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1394.

- Nazarov, P.A.; Kotova, E.A.; Skulachev, V.; Antonenko, Y.N. Genetic Variability of the AcrAB-TolC Multidrug Efflux Pump Underlies SkQ1 Resistance in Gram-Negative Bacteria. Acta Nat. 2019, 11, 93–98.

- Nazarov, P.A.; Sorochkina, A.I.; Karakozova, M.V. New Functional Criterion for Evaluation of Homologous MDR Pumps. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 592283.

- Sulavik, M.C.; Houseweart, C.; Cramer, C.; Jiwani, N.; Murgolo, N.; Greene, J.; DiDomenico, B.; Shaw, K.J.; Miller, G.H.; Hare, R.; et al. Antibiotic Susceptibility Profiles of Escherichia coli Strains Lacking Multidrug Efflux Pump Genes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001, 45, 1126–1136.

- Jo, J.T.H.; Brinkman, F.S.L.; Hancock, R.E.W. Aminoglycoside Efflux in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Involvement of Novel Outer Membrane Proteins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003, 47, 1101–1111.

- Rosenberg, E.Y.; Ma, D.; Nikaido, H. AcrD of Escherichia coli Is an Aminoglycoside Efflux Pump. J. Bacteriol. 2000, 182, 1754–1756.

- Biot, F.V.; Lopez, M.M.; Poyot, T.; Neulat-Ripoll, F.; Lignon, S.; Caclard, A.; Thibault, F.M.; Peinnequin, A.; Pagès, J.-M.; Valade, E. Interplay between Three RND Efflux Pumps in Doxycycline-Selected Strains of Burkholderia thailandensis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e84068.

- Jung, Y.-H.; Shin, E.S.; Kim, O.; Yoo, J.S.; Lee, K.M.; Yoo, J.I.; Chung, G.T.; Lee, Y.S. Characterization of Two Newly Identified Genes, vgaD and vatG, Conferring Resistance to Streptogramin A in Enterococcus faecium. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 4744–4749.

- Hirata, K.; Suzuki, H.; Nishizawa, T.; Tsugawa, H.; Muraoka, H.; Saito, Y.; Matsuzaki, J.; Hibi, T. Contribution of efflux pumps to clarithromycin resistance in Helicobacter pylori. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2010, 25, S75–S79.

- Bosnar, M.; Kelnerić, Z.; Munić, V.; Eraković, V.; Parnham, M.J. Cellular Uptake and Efflux of Azithromycin, Erythromycin, Clarithromycin, Telithromycin, and Cethromycin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 2372–2377.

- Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Huang, N.; Zeng, W.; Xu, W.; Zhou, T.; Shen, M. Comparison of Anti-Microbic and Anti-Biofilm Activity among Tedizolid and Radezolid against Linezolid-Resistant Enterococcus faecalis Isolates. Infect. Drug Resist. 2021, 14, 4619–4627.

- Kim, H.J.; Kim, Y.; Lee, M.S.; Lee, H.S. Gene lmrB of Corynebacterium glutamicum confers efflux-mediated resistance to linco-mycin. Mol. Cells 2001, 12, 112–116.

- Lüthje, P.; Schwarz, S. Molecular analysis of constitutively expressed erm(C) genes selected in vitro in the presence of the non-inducers pirlimycin, spiramycin and tylosin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2006, 59, 97–101.

- Steward, C.D.; Raney, P.M.; Morrell, A.K.; Williams, P.P.; McDougal, L.K.; Jevitt, L.; McGowan, J.E.; Tenover, F.C. Testing for Induction of Clindamycin Resistance in Erythromycin-Resistant Isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2005, 43, 1716–1721.

- Sánchez, M.B.; Martínez, J.L. The Efflux Pump SmeDEF Contributes to Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole Resistance in Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 4347–4348.

- Popella, P.; Krauss, S.; Ebner, P.; Nega, M.; Deibert, J.; Götz, F. VraH Is the Third Component of the Staphylococcus aureus VraDEH System Involved in Gallidermin and Daptomycin Resistance and Pathogenicity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 2391–2401.

- Amiri, G.; Abbasi Shaye, M.; Bahreini, M.; Mafinezhad, A.; Ghazvini, K.; Sharifmoghadam, M.R. Determination of imipenem efflux-mediated resistance in Acinetobacter spp., using an efflux pump inhibitor. Iran. J. Microbiol. 2019, 11, 368–372.

- Mateus, C.; Nunes, A.; Oleastro, M.; Domingues, F.; Ferreira, S. RND Efflux Systems Contribute to Resistance and Virulence of Aliarcobacter butzleri. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 823.

- Jorth, P.; McLean, K.; Ratjen, A.; Secor, P.R.; Bautista, G.E.; Ravishankar, S.; Rezayat, A.; Garudathri, J.; Harrison, J.J.; Harwood, R.A.; et al. Evolved Aztreonam Resistance Is Multifactorial and Can Produce Hypervirulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. mBio 2017, 8, e00517-17.

- Dinesh, N.; Sharma, S.; Balganesh, M. Involvement of Efflux Pumps in the Resistance to Peptidoglycan Synthesis Inhibitors in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 1941–1943.

- Elkins, C.A.; Nikaido, H. 3D structure of AcrB: The archetypal multidrug efflux transporter of Escherichia coli likely captures substrates from periplasm. Drug Resist. Updates 2003, 6, 9–13.

- Nichols, R.J.; Sen, S.; Choo, Y.J.; Beltrao, P.; Zietek, M.; Chaba, R.; Lee, S.; Kazmierczak, K.M.; Lee, K.J.; Wong, A.; et al. Phenotypic Landscape of a Bacterial Cell. Cell 2011, 144, 143–156.

- Galkina, K.V.; Besedina, E.; Zinovkin, R.; Severin, F.F.; Knorre, D.A. Penetrating cations induce pleiotropic drug resistance in yeast. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 8131.

- Lee, A.; Mao, W.; Warren, M.S.; Mistry, A.; Hoshino, K.; Okumura, R.; Ishida, H.; Lomovskaya, O. Interplay between Efflux Pumps May Provide Either Additive or Multiplicative Effects on Drug Resistance. J. Bacteriol. 2000, 182, 3142–3150.

- Tal, N.; Schuldiner, S. A coordinated network of transporters with overlapping specificities provides a robust survival strategy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 9051–9056.

- Somprasong, N.; Hall, C.M.; Webb, J.R.; Sahl, J.W.; Wagner, D.M.; Keim, P.; Currie, B.J.; Schweizer, H.P. Burkholderia ubonensis High-Level Tetracycline Resistance Is Due to Efflux Pump Synergy Involving a Novel TetA(64) Resistance Determinant. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65, e01767-20.

- Bergmiller, T.; Andersson, A.M.C.; Tomasek, K.; Balleza, E.; Kiviet, D.J.; Hauschild, R.; Tkačik, G.; Guet, C.C. Biased partitioning of the multidrug efflux pump AcrAB-TolC underlies long-lived phenotypic heterogeneity. Science 2017, 356, 311–315.

- Snoussi, M.; Talledo, J.P.; Del Rosario, N.-A.; Mohammadi, S.; Ha, B.-Y.; Košmrlj, A.; Taheri-Araghi, S. Heterogeneous absorption of antimicrobial peptide LL37 in Escherichia coli cells enhances population survivability. eLife 2018, 7, 311–315.

- Wu, F.; Tan, C. Dead bacterial absorption of antimicrobial peptides underlies collective tolerance. J. R. Soc. Interface 2019, 16, 20180701.

- Bhattacharyya, S.; Walker, D.M.; Harshey, R.M. Dead cells release a ‘necrosignal’ that activates antibiotic survival pathways in bacterial swarms. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4157.

- Björkholm, B.; Sjölund, M.; Falk, P.G.; Berg, O.G.; Engstrand, L.; Andersson, D.I. Mutation frequency and biological cost of antibiotic resistance in Helicobacter pylori. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 14607–14612.

- Long, H.; Miller, S.F.; Strauss, C.; Zhao, C.; Cheng, L.; Ye, Z.; Griffin, K.; Te, R.; Lee, H.; Chen, C.-C.; et al. Antibiotic treatment enhances the genome-wide mutation rate of target cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E2498–E2505.

- El Meouche, I.; Dunlop, M.J. Heterogeneity in efflux pump expression predisposes antibiotic-resistant cells to mutation. Science 2018, 362, 686–690.

- Reams, D.; Roth, J.R. Mechanisms of Gene Duplication and Amplification. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2015, 7, a016592.

- Du, D.; Wang-Kan, X.; Neuberger, A.; Van Veen, H.W.; Pos, K.M.; Piddock, L.J.V.; Luisi, B.F. Multidrug efflux pumps: Structure, function and regulation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 523–539.

- Nikaido, H. RND transporters in the living world. Res. Microbiol. 2018, 169, 363–371.

- Pasqua, M.; Grossi, M.; Zennaro, A.; Fanelli, G.; Micheli, G.; Barras, F.; Colonna, B.; Prosseda, G. The Varied Role of Efflux Pumps of the MFS Family in the Interplay of Bacteria with Animal and Plant Cells. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 285.

- Hassan, K.A.; Liu, Q.; Elbourne, L.; Ahmad, I.; Sharples, D.; Naidu, V.; Chan, C.L.; Li, L.; Harborne, S.; Pokhrel, A.; et al. Pacing across the membrane: The novel PACE family of efflux pumps is widespread in Gram-negative pathogens. Res. Microbiol. 2018, 169, 450–454.

- Bot, C.T.; Prodan, C. Quantifying the membrane potential during E. coli growth stages. Biophys. Chem. 2010, 146, 133–137.

- Zorova, L.D.; Popkov, V.A.; Plotnikov, E.Y.; Silachev, D.N.; Pevzner, I.B.; Jankauskas, S.S.; Babenko, V.A.; Zorov, S.D.; Balakireva, A.V.; Juhaszova, M.; et al. Mitochondrial membrane potential. Anal. Biochem. 2018, 552, 50–59.

- Silhavy, T.J.; Kahne, D.; Walker, S. The Bacterial Cell Envelope. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2010, 2, a000414.

- Rybenkov, V.V.; Zgurskaya, H.I.; Ganguly, C.; Leus, I.V.; Zhang, Z.; Moniruzzaman, M. The Whole Is Bigger than the Sum of Its Parts: Drug Transport in the Context of Two Membranes with Active Efflux. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 5597–5631.

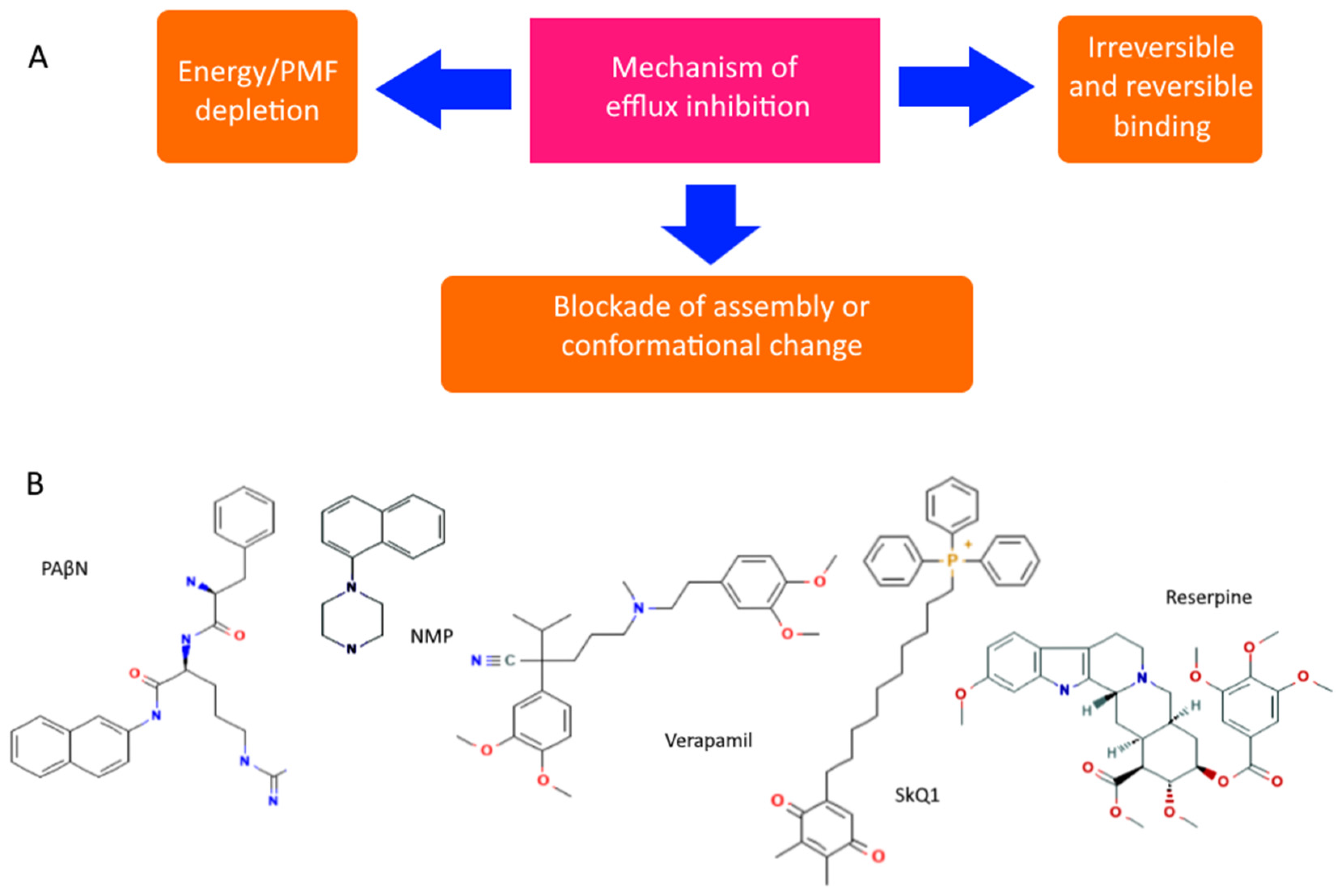

- Verma, P.; Tiwari, M.; Tiwari, V. Efflux pumps in multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: Current status and challenges in the discovery of efflux pumps inhibitors. Microb. Pathog. 2021, 152, 104766.

- Stavri, M.; Piddock, L.J.V.; Gibbons, S. Bacterial efflux pump inhibitors from natural sources. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2006, 59, 1247–1260.

- Lomovskaya, O.; Warren, M.S.; Lee, A.; Galazzo, J.; Fronko, R.; Lee, M.; Blais, J.; Cho, D.; Chamberland, S.; Renau, T.; et al. Identification and Characterization of Inhibitors of Multidrug Resistance Efflux Pumps in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Novel Agents for Combination Therapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001, 45, 105–116.

- Lamers, R.P.; Cavallari, J.F.; Burrows, L.L. The Efflux Inhibitor Phenylalanine-Arginine Beta-Naphthylamide (PAβN) Permeabilizes the Outer Membrane of Gram-Negative Bacteria. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e60666.

- Radchenko, M.; Symerský, J.; Nie, R.; Lu, M. Structural basis for the blockade of MATE multidrug efflux pumps. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7995.