Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Rita Xu and Version 1 by Joshua Edokpayi.

Wetlands are important ecosystems with physical and socioeconomic benefits. A wetland is defined as an area of soil covered with water or has water close to its surface all year or at some periods of the year. They are necessary for people’s livelihoods but not usually considered important.

- wetland

- South Africa

- wetland functions

1. Introduction

Wetlands are mostly found in humid regions and in moistened provinces [2][1], which implies that climatic conditions aid the occurrence of wetlands. They are categorised as marine, coastal, and inland systems [3][2]. Wetlands are characterised by the presence of hydrophytes, which can grow and reproduce in anaerobic soil conditions. Due to this, leaves and stems of wetland plants are often hollow and/or spongy [2][1].

Wetlands function for physical and economic benefits. The term “wetland value” connotes the direct benefit of the wetland, while “wetland function” is the indirect benefit. These benefits may include water storage, protection from storm, flood control and prevention, drought buffering, erosion control, groundwater recharge and discharge, shoreline stabilization, retention of nutrients, water purification, and stabilization of local climate conditions, especially temperature and rainfall [4][3]. Wetlands are economically important in the water supply [5,6,7][4][5][6]. The prominent need for water as a vital source of life and need for decontamination of water, as described by Adeeyo et al. [8][7], makes wetlands important since they also function for water treatment. They are capable of cleaning impurities from wastewater facilities and delivering purified water to the ecosystem [7][6]. Wetlands function for neutralising some contaminants, capturing sediment, and decontaminating water. Therefore, they can be regarded as natural filters. Wetlands have been reported to confer protection against weak storms and in states with relatively weak buildings. Additionally, they function for the enhancement of quality of water in water bodies. Furthermore, innumerable foods exist in wetlands, which tend to bring together uncountable animal species [9][8].

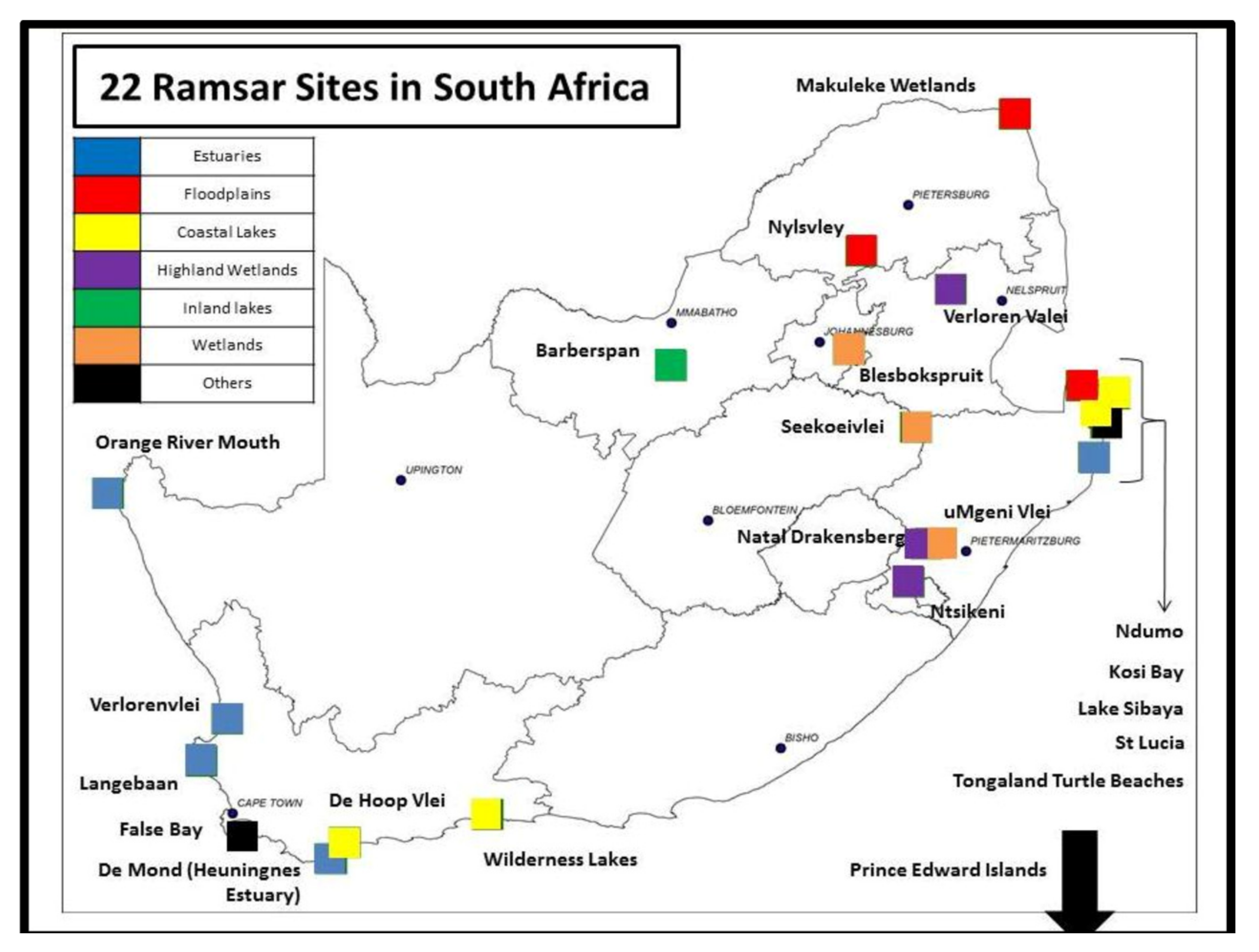

South Africa has been reported as a water-scarce country [10][9] due to characteristic low rainfall. Therefore, the water resources available have to be well-conserved to help with this problem of water scarcity. Wetlands have been reported to function for the purification of water and its treatment; hence they are useful in water conservation. In South Africa, wetlands cover a total of 29,000 km2, which is only about 2.4% of the entire land area [11][10], and there is need for the best management strategies to avoid extinction of the existing limited wetland resources [12][11]. Wetlands in South Africa are characterised by the availability of surface water and or underground water and the presence of hydric soils [13,14][12][13]. However, wetlands in South Africa, though limited, are still faced with the challenge of degradation. This degradation is leading to a reduction in the number of wetlands available and ultimately reducing the amount of quality and safe water available for use. Hence, South Africa was chosen as a case study for the reason of water scarcity. For wise utilisation of wetlands, South Africa decided to adopt the wetland policy from Ramsar (an international treaty for the conservation and sustainable use of wetlands, named after the city of Ramsar in Iran) in order to conserve and manage them wisely [12][11]. The distribution of notable Ramsar wetlands in South Africa is shown in Figure 1.

Although wetlands occur in nature, artificial wetlands exist that function just like natural wetlands and are created to reduce the pressure on natural ones. The underestimation of wetland benefits is expressed in their loss with about 64% being lost since 1990 [15][14]. The wetland ecosystem and its resources are under threat from human activities and global warming. Wetlands are impacted by anthropogenic activities such as agriculture, human settlement, mining, and others that alter the quality and quantity of water within the wetlands. Therefore, the conservation of available wetlands is of great necessity. A careful study of wetlands is necessary to help the conservation of this natural filter and will increase the amount of water available. Although there are fragments of literature discussing wetlands, these reports are independently focused on different aspects such as classification, pollution, and protection. However, this review is a comprehensive assemblage of these fragments about wetland resources in South Africa. This paper is expected to give answers to the question of the current state of wetland management in South Africa. It will also give insight into the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and solution strategies on wetland management in South Africa.

2. Wetlands and Their Classifications in South Africa

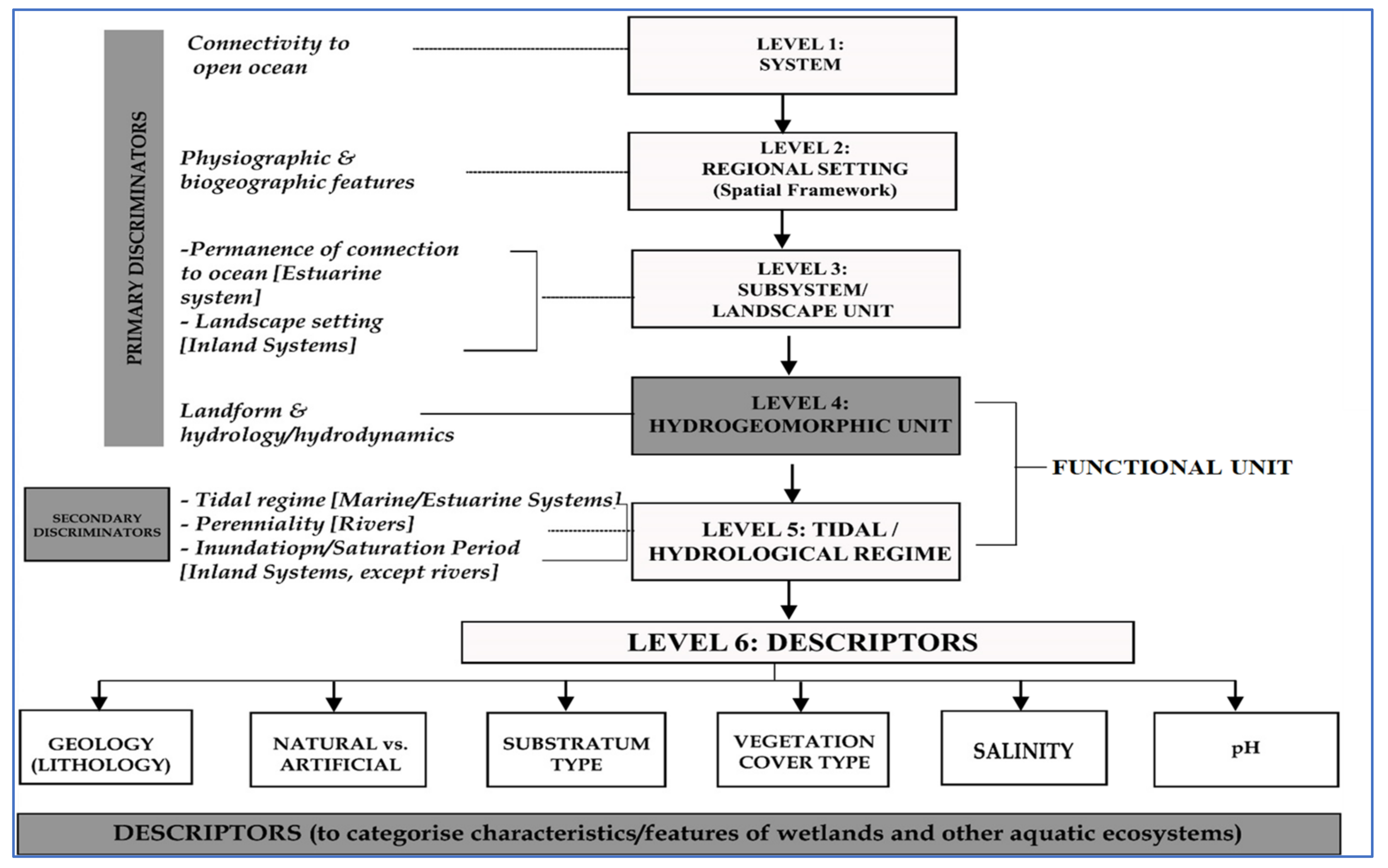

Wetlands are classified based on their biophysical properties such as plant species, soils, hydrology, animal types, function, and value [17][16]. Classification may be conducted for mapping, planning, acquisition, regulatory, and other purposes [18,19][17][18]. According to the Cowardin system, wetlands can be classified based on landscape, vegetation, and hydrologic regime as marine, tidal, lacustrine, palustrine, and riverine [3][2]. Based on their connectivity to open ocean, wetlands are classified as marine, estuary, and inland; however, there is a fourth category called artificial wetland, which is human-made but functions just as the natural types [10,20][9][19]. Figure 2 shows the classification of wetlands showing the different relationships among the different structures of classification.

The tiered structure moves from systems (marine vs. estuarine vs. inland) at the widest scale (Level 1), to regional and landscape units (Levels 2 and 3), and to hydrogeomorphic units as the finest spatial structure (Level 4). At Level 5, inland systems are separated based on the hydrological regime and, in the case of open water bodies, the inundation depth class. At Level 6, six ‘descriptors’ are used for the classification. These descriptors present a clear difference between the aquatic ecosystems with different structural, chemical, and/or biological characteristics [20][19].

2.1. Marine Wetlands

A marine system has been described to be the open sea part covering the continental shelf and/or its related shoreline and reaches up to 10 m at low tide [21][20]. Examples of marine/coastal wetlands are open coast, estuaries, tidal flats, coral reefs, mangrove forests, and coastal lagoons. In 2011, SANBI further classified marine and coastal habitats in South Africa into three, namely offshore, inshore, and coastal areas. The offshore areas consist of offshore pelagic and offshore benthic zones. The inshore zones include areas characterised by rocky or unconsolidated substrate. The third category, the coastal areas, is subdivided into rocky coast, mixed coast, and sandy coast. Marine wetlands are important habitats for fishes, dugongs, and marine turtles. Plants present include pig face, sea rush, marine couch, creeping bookweed, and swamp weed [22][21]. Based on wave exposure, geology, grain size, and/or beach state, the marine groups are classified into 14 categories [3][2]. These classifications alongside biogeographical differences (based on the delineation of marine “ecozones” and “ecoregions”) are used to regionalise the classes. This will result in a total of 136 marine and coastal habitats, 41 of which are shallow and less than 5 m in depth where marine and coastal wetlands tend to occur [20,23][19][22].

2.2. Estuarine Wetlands

Estuary wetlands are partially enclosed, and they contain water bodies that are always or sometimes open to the sea or on decadal timescales. Estuarine systems include estuarine bays, river mouths, estuarine lakes, permanently open estuaries, and temporarily open estuaries. Currently, the classification system for the estuary component of the 2011 National Biodiversity Assessment (NBA) was developed using different approaches considering the following four physical characteristics: estuary size, mouth state (permanently open or temporarily open/closed), salinity structure (fresh or mixed), and catchment type (turbid, black, or clear based on the colour of the inflowing river) [24][23]. The majority of the estuaries along the coast of South Africa have river catchments with conditions differing from those in adjacent marine inshore, that is, they are calm, sheltered, and shallow. They provide important nurseries for many species of marine fishes.

South Africa’s climate has a great effect on estuaries. They are affected by global warming characteristics such as rise in temperature, rainfall, sea level rise, storm disturbance, pH, and carbon dioxide [25][24]. This classification of features was presented together with the category of the biogeographical region to raise 46 estuarine ecosystem types for South Africa. The following estuarine habitats have been identified: water surface (estuary channel), rock, sand, and mudflats. The following plant communities have been identified including intertidal/subtidal macroalgal, submerged macrophytes, intertidal/supratidal saltmarsh, reed sand sedges, mangroves, and swamp forest [26][25]. The estuaries within South Africa with some level of protection are given in Table 1. A total of 84 fish species and 35 bird species are targeted for estuaries as presented by van Niekerk and Turpie [26][25]. The fish species include: Acanthopagrus berda, Ambasssis natalensis, Caranx papuensis, Elops machnata, Lichia amia, Liza alata, Pseudorhombus arsius, Solea bleekeri, Terapon jarbua, Syngnathus acus, and Valamguli seheli. The bird species include great white pelican, greater flamingo, grey plover, red knot, little stint, sanderling, swift tern, little tern, mangrove kingfisher, pink backed pelican, and squacco heron.

Table 1. Some protected estuaries in South Africa.

| S/N | Estuary | Protected Area | Agency | Level of Protection | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Orange | Planned | Provincial | Medium | |||

| 2 | Spoeg | Namaqualand NP | SANParks | Medium | |||

| 3 | Groen | Namaqualand NP | KwaZulu-NatalSANParks | Medium | |||

| 4 | Diep | Rietvlei NR | Municipal | Low | |||

| Nylsvley Nature Reserve | Floodplain | Limpopo | 5 | Krom | Table Mountain | SANParks | High |

| Verlorenvlei | Highland wetland | Western Cape | 6 | Wildevoelvlei | Table Mountain | SANParks | Low |

| De Hoop | Costal lake | Western Cape | 7 | Sand | Sandvlei NR | Municipal | Low |

| Langebaan | Estuary | Western Cape | 8 | Ratel | Agulhas NP | SANParks | |

| Wilderness lakes | Medium | ||||||

| Costal lake | Western Cape | 9 | Heuningnes | De Mond NR | CapeNature | Medium | |

| Verlorenvlei | Highland wetland | Western Cape | 10 | Goukou | Stilbaai MPA | CapeNature | Medium |

| Orange River Mouth | Estuary | Northern Cape | 11 | Wilderness | Wilderness Lakes NP | SANParks | Low |

| Lake Sibaya | Costal lake | KwaZulu-Natal | 12 | Swartvlei | |||

| Ntsikeni | Wilderness Lakes NP | Highland wetland | KwaZulu-NatalSANParks | Low | |||

| 13 | Goukamma | Goukamma NR | CapeNature | Medium | |||

| Barberspan | Inland lakes | North West | 14 | Knysna | Knysna NP | SANParks | |

| Natal Drankensberg | Low | ||||||

| Estuary | KwaZulu-Natal | 15 | Keurbooms | Keurbooms River NR | CapeNature | Low | |

| Kosi Bay | Costal lake | KwaZulu-Natal | 16 | Sout | De Vasselot NP | SANParks | Medium |

| ST. Lucia | Estuary | KwaZulu-Natal | 17 | Groot (W) | Tsitsikamma NP | SANParks | High |

| Verloren Vallei Nature Reserve | Highland wetland | Mpumalanga | 18 | Bloukrans | Tsitsikamma NP | SANParks | High |

| 19 | Lottering | Tsitsikamma NP | SANParks | High | |||

| 20 | Elandsbos | Tsitsikamma NP | SANParks | High | |||

| 21 | Storms | Tsitsikamma NP | SANParks | High | |||

| 22 | Elands | Tsitsikamma NP | SANParks | High | |||

| 23 | Groot (E) | Tsitsikamma NP | SANParks | High | |||

| 24 | Tsitsikamma | Huisklip NR | EC Parks | Low | |||

| 25 | Seekoei | Seekoei River NR | Municipal | Low | |||

| 26 | Gamtoos | Gamtoos R. Mouth NR | Municipal | Low | |||

| 27 | Van Stadens | Van Stadens NR | Municipal | Low | |||

| 28 | Sunday | Addo Elephant NR | Municipal | Medium | |||

| 29 | Nahoon | Nahoon Estuary NR | Municipal | Low | |||

| 30 | Mendu | Dwesa-Cwebe MPA | DEA/DAFF | Medium | |||

| 31 | Mendwana | Dwesa-Cwebe MPA | DEA/DAFF | Medium | |||

| 32 | Mbashe | Dwesa-Cwebe NR | DEA/DAFF | High | |||

| 33 | Ku-Mpenzu | Dwesa-Cwebe NR | EC Parks | Medium | |||

| 34 | Ku-Bhula/Mbhanyana | Dwesa-Cwebe NR | EC Parks | Medium | |||

| 35 | Kwa-Suka | Dwesa-Cwebe NR | EC Parks | Medium | |||

| 36 | Ntlonyane | Dwesa-Cwebe NR | EC Parks | Medium | |||

| 37 | Nkanya | Dwesa-Cwebe NR | EC Parks | Medium | |||

| 38 | Hluleka | Hluleka NR | EC Parks | Low | |||

| 39 | Nkodusweni | Pondoland MPA | DEA | Low | |||

| 40 | Mtafufu | Pondoland MPA | DEA | Low | |||

| 41 | Mzimpunzi | Pondoland MPA | DEA | Low | |||

| 42 | Mzimpunzi | Pondoland MPA | DEA | Low | |||

| 43 | Kwa-Nyambalala | Pondoland MPA | DEA | Low | |||

| 44 | Mbotyi | Pondoland MPA | DEA | Low | |||

| 45 | Mkozi | Pondoland MPA | DEA | Low | |||

| 46 | Myekane | Pondoland MPA | DEA | Low | |||

| 47 | Sitatsha | Pondoland MPA | DEA | Low | |||

| 48 | Lupatana | Pondoland MPA | DEA | Low | |||

| 49 | Mkweni | Pondoland MPA | DEA | Low | |||

| 50 | Msikaba | Mbambati NR | EC Parks | High | |||

| 51 | Butsha | Mbambati NR | EC Parks | High | |||

| 52 | Mgwegwe | Mbambati NR | EC Parks | High | |||

| 53 | Mgwetyana | Mbambati NR | EC Parks | High | |||

| 54 | Mtentu | Mbambati NR | EC Parks | High | |||

| 55 | Sikombe | Pondoland MPA | DEA | Low | |||

| 56 | Kwanyana | Pondoland MPA | DEA | Low | |||

| 57 | Mtolane | Pondoland MPA | DEA | Low | |||

| 58 | Mnyameni | Pondoland MPA | DEA | Low | |||

| 59 | Mpahlanyana | Pondoland MPA | DEA | Low | |||

| 60 | Mpahlane | Pondoland MPA | DEA | Low | |||

| 61 | Mzamba | Pondoland MPA | DEA | Low | |||

| 62 | Mtentwana | Pondoland MPA | DEA | Low | |||

| 63 | Mtamvuna | Pondoland MPA | DEA | Low | |||

| 64 | Mpenjati | Mpenjati NR | EKZNW | Medium | |||

| 65 | Mgeni | Beechwood NR | EKZNW | Medium | |||

| 66 | Mhlanga | - | EKZNW | High | |||

| 67 | Mlalazi | Mlalazi NR | EKZNW | High | |||

| 68 | Mhlathuze | - | EKZNW | Medium | |||

| 69 | St Lucia-Mfolozi | iSimangaliso WP | ISWP Authority | High/Medium | |||

| 70 | Mgobozeleni | iSimangaliso WP | EKZNW | Low | |||

| 71 | Kosi | iSimangaliso WP | EKZNW | Medium |

2.3. Inland Wetlands

Inland systems are characteristically different from marine and coastal wetlands in that they are not connected to the ocean. Inland wetlands, examples of which are marshes and wet meadows, do not have a marine exchange and/or tidal influence [20,23][19][22]. These wetlands are dominated by herbaceous plants, while swamps are dominated by shrubs, and wooded swamps are dominated by trees [27][26]. Some of the Ramsar sites in South Africa along with their wetland types and location are presented in Table 2. Wetlands in KwaZulu-Natal are classified into three-level categories consisting of 16 wetland types based on the national wetland vegetation description [28][27]. These Ramsar sites are well-protected except Orange River Mouth in the Northern Cape and Verlorenvlei in the Western Cape, which are not formally protected [5][4]. Although wetlands are valuable, they are being lost due to impoundment, irrigation, hydroelectricity generation, food insecurity, population growth, and alien invasive biota [29][28].

Table 2. Some Ramsar sites in South Africa.

| Wetland Name | Wetland Type | Location |

|---|---|---|

| De Mond Nature Reserve (Heuningnes Estuary) |

Estuary | Western Cape |

| Makuleke Wetlands | Floodplain | Limpopo |

| The Ndumo Game Reserve | Floodplain |

References

- Eco-Pulse. ICLEI Wetland Management Guidelines—Building Capacity and Supporting Effective Management of Wetlands within South African Municipalities, 3rd ed.; Preliminary Version; Eco-Pulse: Hilton, South Africa, 2018.

- United Nations Environmental Protection Agency. Classification and Types of Wetland. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/wetlands/classification-and-types-wetlands#undefined (accessed on 11 December 2021).

- Rafiq, R.; Alam, S.; Rahman, M.; Islam, I. Conserving wetlands: Valuation of indirect use of benefits of a wetland of Dhaka. Inter. J. Environ. Sci. Dev. 2013, 5, 64–69.

- Von Staden, L. Planning for Improved Threatened Species Conservation. SANBI 2013. Available online: http://opus.sanbi.org/bitstream/20.500.12143/7278/1/BPF2013_Planning%20for%20improved%20threatened%20species%20conservation_Von%20Staden.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2021).

- Nemutamvuni, K. Multi-Stakeholder Management of a Wetland in the City of Tshwane: The Case of Colbyn. Ph.D. Thesis, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa, 2018.

- Skowno, A.L.; Poole, C.J.; Raimondo, D.C.; Sink, K.J.; Van Deventer, H.; Van Niekerk, L.; Harris, L.R.; SmithAdao, L.B.; Tolley, K.A.; Zengeya, T.A.; et al. National Biodiversity Assessment 2018: The Status of South Africa’s Ecosystems and Biodiversity; Synthesis Report; South African National Biodiversity Institute: Pretoria, South Africa, 2019; pp. 1–214.

- Adeeyo, A.O.; Odelade, K.A.; Msagati, T.A.M.; Odiyo, J.O. Antimicrobial potencies of selected native African herbs against water microbes. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2020, 32, 2349–2357.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Distance Learning Models on Watershed Management. Available online: http://www.epa.gov/watertrain (accessed on 11 December 2021).

- Ollis, D.J.; Jennifer, A.D.; Mbona, N.; Dini, J.A. South African Wetlands: Classification of Ecosystem Types. In The Wetland Book; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 1–13.

- Dini, J.; Everard, M. National Wetland Policy: South Africa. In The Wetland Book; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 1–6.

- Department of Environmental Affairs. What You Should Know about South Africa’s Wetlands; Ramsar Convention on Wetlands: Ramsar, Iran, 2018.

- Braack, A.M.; Walters, D.; Kotze, D.C. Practical Wetland Management. In South Africa: Rennies Wetlands Project; Ecosystem Marketplace: Washington, DC, USA, 2000.

- Sakana, N.; Alvarez, M.; Boehme, B.; Handa, C.; Wangechi, H.; Langensiepen, M.; Menz, G.; Misana, S.; Mogha, N.; Moseler, B.M.; et al. Classification, characterisation and use of small wetlands in East Africa. Wetlands 2011, 31, 1103–1116.

- Ramsar Convention on Wetlands. Wetlands: A Global Disappearing Act; Fact Sheet 3.1; Ramsar Convention on Wetlands: Ramsar, Iran, 2015.

- Kock, A. Diatom Diversity and Response to Water Quality within the Makuleke Wetlands and Lake Sibaya. Master’s Dissertation, Potchefstroom Campus of the North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa, 2017.

- Ewart-Smith, J.L.; Ollis, D.J.; Day, J.A.; Malan, H.L. National Wetland Inventory: Development of a Wetland Classification System for South Africa; WRC Report No. KV 174/06; Water Research Commission: Pretoria, South Africa, 2006.

- Ollis, D.; Snaddon, K.; Job, N.; Mbona, N. Classification System for Wetlands and Other Aquatic Ecosystems in South Africa; SANBI: Cape Town, South Africa, 2013.

- Ellery, W.N.; Grenfell, S.E.; Grenfell, M.C.; Powell, R.; Kotze, D.C.; Marren, P.M.; Knight, J. Wetlands in Southern Africa; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016.

- Makopondo, R.O.B.; Rotich, L.; Kamau, C.G. Potential use and challenges of constructed wetlands for wastewater treatment and conservation in game lodges and resorts in Kenya. Sci. World J. 2020, 2, e9184192.

- Ollis, D.J.; Ewart-Smith, J.L.; Day, J.A.; Job, N.M.; Macfarlane, D.M.; Snaddon, C.D.; Sieben, E.J.J.; Dini, J.A.; Mbona, N. The development of a classification system for inland aquatic ecosystems in South Africa. Water SA 2015, 41, 727–745.

- NSW Department of Planning. Industry and Environment. Available online: https://www.environment.nsw.gov.au/topics/water/wetlands/plants-and-animals-in-wetlands/plants (accessed on 27 July 2021).

- SANBI. The South African National Biodiversity Institute Is Thanked for the Use of Data from the National Herbarium; Pretoria (PRE) Computerized Information System (PRECIS): Pretoria, South Africa, 2009.

- Van Niekerk, L.; Turpie, J.K. South African National Biodiversity Asessment 2011; Technical Report: Volume 3: Estuary Component. CSIR Report Number CSIR/NRE/ECOS/ER/2011/0045/B; CSIR: Stellenbosch, South Africa, 2012.

- James, N.C.; Niekerk, L.V.; Whitfiled, A.K.; Potts, W.M.; Gotz, A.; Paterson, A.W. Effects of climate change on South African estuaries and associated fish species. Clim. Res. 2013, 57, 233–248.

- van Niekerk, L.; Adams, J.B.; James, N.C.; Lamberth, S.J.; MacKay, C.F.; Turpie, J.K.; Rajkaran, A.; Weerts, S.P.; Whitfield, A.K. An estuary ecosystem classification that encompasses biogeography and a high diversity of types in support of protection and management. Afr. J. Aquat. Sci. 2020, 45, 199–216.

- EPA. What Is a Wetland? Available online: https://www.epa.gov/wetlands/what-wetland (accessed on 27 July 2021).

- Rivers-Moore, N.A.; Goodman, P.S. River and wetland classifications for freshwater conservation planning in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa. Afr. J. Aquat. Sci. 2010, 35, 61–72.

- Mitchell, S.A. The status of wetlands, threats and the predicted effect of global climate change: The situation in Sub Sahara Africa. Aquat. Sci. 2013, 75, 95–112.

More