Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Elizabeth Armstrong-Mensah and Version 2 by Catherine Yang.

This notwithstanding, HIV continues to be a global public health issue. Many HIV patients died from acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) related illnesses globally. Without addressing HIV-related stigma, 2030 (SDG 3) will be a very distant reality, as HIV-related stigma has been identified as a major drawback in HIV counselling and testing (VCT) uptake and ART utilization and adherence.

- HIV prevention

- voluntary counselling and testing

- antiretroviral therapy

- HIV-related stigma

1. Antiretroviral Therapy

Antiretroviral therapy is a pharmacological preparation designed to target HIV at key points of its life cycle [1][35]. Its aim is to minimize the risk of HIV and to reduce HIV viral load in blood, semen, and genitalia [2][36]. In 1987, the United States (US) Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first ART drug, zidovudine, to treat HIV [3][37]. Zidovudine is a nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI), which upon phosphorylation, competes with free floating cytoplasmic nucleotides during the conversion of viral RNA into DNA [4][38]. This mechanism results in the termination of viral DNA formation. In 1995, the US FDA approved another ART, saquinavir, a protease inhibitor required for inhibiting the replication of HIV, and in 1996, nevirapine, a non-nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) was approved by the US FDA [5][39]. Following the establishment of the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) in 2003 by George W. Bush, enfuvirtide, another ART, which is an entry and fusion inhibitor, was approved. Since its launch, PEPFAR has supported life-saving ART for over 20 million people and prevented millions from acquiring HIV in over fifty countries across the globe, especially those in sub-Saharan Africa [6][40]. In 2012, the first integrase inhibitor, raltegravir, followed by emtricitabine-tenofovir, which are both used as treatments for preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP), were also approved [7][41]. Due to ART, the life expectancy of the about 38 million people living with HIV in 2018 globally, was close to that of people not living with HIV [8][42].

Antiretroviral therapy can prevent HIV transmission. In 2010, the Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis Initiative (iPrEx) conducted a double-blinded, placebo-controlled Phase III clinical trial. Results from the trial showed that when taken every 24 h, PrEP can cause a 44% reduction in HIV infection risk and can also reduce infection rates by 73% [9][43]. In 2011, the HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN 052) also conducted a phase III two-arm randomized controlled multi-center trial to ascertain the potential of ART to prevent sexual transmission of HIV-1 in serodiscordant couples. Study findings reported in 2015, showed a 93% reduction in HIV transmission among 1171 serodiscordant couples [10][44]. Results from the most recent HPTN 084 study in 2020 showed the efficacy of the PrEP cabotegravir, an extended-release injectable suspension, when administered once every two months [11][45]. Consequently, on 20 December 2021, the US FDA licensed cabotegravir for at-risk adults and adolescents who weigh at least 35 kg [12][46]. Cabotegravir is administered as two initiation injections: a month apart and subsequently, every two months.

In July 2020, the antiretroviral (ARV) medication dapivirine was incorporated into the dapivirine vaginal ring (DVR). The ring is made of silicone and infused with ARV. It slowly releases ARV medication throughout the month and is known to reduce the risk of HIV infection by 61% [13][47]. In March 2022, the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority (SAHPRA) approved DVR for use by women aged 18 years and older to reduce their HIV risk [14][48]. It is important to note that when ART, whatever the form, is used consistently as prescribed by a physician, the HIV viral load in blood, sperm, vaginal fluid, and rectal fluids can be significantly reduced to undetectable levels. This is referred to as viral suppression or an ‘undetectable’ viral burden [15][49]. At this level, the risk of transmission is absent or reduced significantly.

2. Global HIV Prevention Challenges

2.1. Voluntary Counselling and Testing

Regardless of the expansion of VCT services globally, challenges persist [16][17][18][7,10,18]. Due to financial constraints, the cost of investment, and the lack of medical infrastructure, laboratory and trained health care providers, VCT is not a national priority for many governments, especially those in sub-Saharan Africa. As most of these countries depend on donor support to fund VCT services, they find it difficult to make VCT accessible to their entire population [17][19][10,11]. Structural barriers such as the distance between one’s residence and the nearest public health facility as well as delays in the reception of HIV test results due to the high workload and burnout of health care providers, have been linked to declining VCT uptake [20][54]. Indeed, increased complaints of health care provider burnout in Kenya, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe almost disrupted VCT services [21][55]. In countries where lay counselors are used to provide HIV counseling services to reduce the workload of health care providers, precarious working conditions and the financial instability of the lay counselors has made the strategy unsustainable [20][54]. Low levels of awareness of the benefits of VCT services in developing countries is another challenge that impedes VCT effectiveness. In 2014, UNAIDS reported that 19 developing countries were experiencing challenges in raising community awareness of the benefits of VCT [22][56]. That year, Nigeria and Kenya had an awareness level of 34% and 41% respectively, compared to an average level of 72% in developed countries [23][57]. The fear of stigma, lack of test confidentiality, and poor treatment from health care providers serve as further challenges to global VCT testing uptake [18][24][18,58]. The stigmatization and criminalization of HIV has caused certain populations (lesbians, gay, bisexuals, transgender or intersex, drug users, men who have sex with men (MSM), sex workers, and sexually active young people) to refrain from getting tested for fear of being diagnosed with HIV, which could result in maltreatment, extortion, discrimination, violence, or arrest [22][56]. In a study conducted on 45,000 gay men in 28 sub-Saharan African countries including Nigeria, Malawi, and Kenya, researchers found that only 50% of study participants had tested for HIV in the past year. The researchers attributed the low VCT uptake to the anti- lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) laws, which they said promote discrimination and stigmatization of HIV among this population [21][55]. The results of a study conducted in sub-Saharan African on factors that prevent HIV testing showed that the cost of HIV testing negatively impacts VCT access and uptake [17][25][26][9,10,21]. The coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) has also negatively impacted VCT uptake. Owing to a national lockdown as a measure to contain the spread of COVID-19, VCT services and ART initiation were interrupted in 65 clinics in South Africa [27][59]. Regardless of its benefits, the comprehensive implementation of PITC in sub-Saharan Africa is woefully inadequate [28][60] due to inadequate training and shortage of trained health care workers, increased workload of health care providers, and inadequate space for providing confidential counseling services [29][30][61,62]. A study conducted to assess institutional capacity to implement PITC in Zimbabwe found that while most sites had staff, they were not many, and most of the testing was done by nurses, with laboratory technologists providing quality control. In situations where laboratory technologists conducted the test, patients experienced delays in receiving their results, causing some not to return to facilities for their results [31][63]. Regarding space, only 10 of the 16 sites involved in the study had adequate space to provide confidential counseling services [31][63]. Currently, there are global debates on patient perceptions of PITC. Although several studies have documented high patient acceptance of the approach, it is unclear the extent to which this is accurate, as intentional and unintentional coercion by health care providers, as well as other factors, may influence patient decision-making at the point of testing [32][30]. Despite the success of the FBIT approach, there are some barriers that impact its extensive utilization. These barriers include the difficulty of people disclosing their HIV status to family members, and the fear of psychological instability especially among children [33][34][35][36][64,65,66,67]. In a study conducted in Ghana, it was found that despite participants’ willingness to provide information about family members, they were fearful of possible stigmatization and discrimination once their HIV status was disclosed [37][68]. Fear was found to be a barrier to the implementation of the FBIT approach [38][69].2.2. Antiretroviral Therapy

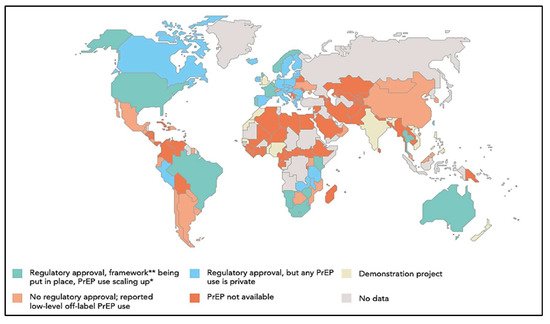

Overall, global estimates show that regardless of the significant progress made in ART coverage, the lack of adequately trained health care providers who can effectively dispense and monitor ART in some sub-Saharan African countries serve as a major drawback in the scaling up of ART coverage [39][70]. In some sub-Saharan African countries like Ghana, the shortage of ART, and the non-adherence to ART by PLWH are the major challenges [40][71]. In the WHO Eastern Mediterranean region, a “testing gap” (the gap between the estimated number of PLWH and the number of PLWH who know that they are infected), as well as the region’s vast reliance on donor support, have been identified as responsible for low ART coverage. In Latin America and the Caribbean regions, the lack of medication adherence associated with substance abuse, HIV- related stigma, depressive symptoms, and high pill burden are the challenges [41][72]. While the WHO European region has one of the lowest HIV prevalence rates, it has the highest ART coverage. However, unlike some PLWH in low and -middle-income countries who have free access to ART, PLWH in France have to pay for ART, which can be expensive [42][73]. In the WHO Western Pacific region, the Philippines has the highest HIV transmission rate and yet, the lowest ART coverage. This is due to the uneven distribution of HIV treatment centers across the country’s approximately 7000 islands [43][74]. Despite the launching of a 2025 agenda to end HIV transmission, PLWH in Australia are challenged with the high cost of ART and HIV-related stigma, and in the WHO South-East Asia region as in the Eastern Mediterranean region, the over dependence on donor assistance, which has been dwindling over the years [44][75], has negatively impacted ART coverage. As of June 2018, 46 countries had obtained regulatory approval for PrEP, and 39 of those countries have included PrEP usage within their HIV policies [45][76]. Figure 12 shows trends in global PrEP regulatory approval. In the Americas, the United States, Canada, and Brazil have obtained regulatory approval for PrEP. In the European region, PrEP is available in only Norway, France, Portugal, Belgium, and the United Kingdom. In the Western Pacific region only Australia has obtained regulatory approval for PrEP utilization. In the South-East Asia region, two countries, Thailand and Malaysia have obtained regulatory approval for PrEP utilization. Out of the 54 countries in Africa, only four (South Africa, Namibia, Kenya, and Zimbabwe) have obtained regulatory approval for PrEP [46][77].

Figure 12. Availability of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis by Country culled from United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Ending AIDS—Progress Towards the 90-90-90 Targets. Available online: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/Global_AIDS_update_2017_en.pdf, accessed on 24 December 2021 [46][77]. * PrEP scale up among men who sleep with men; ** A framework for PrEP scale-up includes clinical guidelines; service provider training; access-oriented PrEP services; use of generic PrEP, price subsidy or reimbursement; effective demand creation.