The aim of this systematic review is to shed light on the challenges of whole ovary cryopreservation and transplantation and to summarize the solutions that have been proposed so far in animal experiments and humans in order to stimulate further research in the field.

- whole ovary

- cryopreservation

- vascular anastomosis

- microsurgery

1. Introduction

Ovarian tissue cryopreservation and transplantation is the only fertility preservation option that enables both restoration of fertility and resumption of ovarian endocrine function, avoiding the morbidity associated with premature menopause. It is also the only technique available to prepubertal patients and those whose treatment cannot be delayed for life-threatening reasons. Ovarian tissue cryopreservation can be done in two different ways, either as ovarian cortical fragments or as a whole organ with its vascular pedicle. Although use of cortical strips is the only procedure that has been approved by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, it is fraught with drawbacks, the major one being serious follicle loss occurring after avascular transplantation due to prolonged warm ischemia. Whole ovary cryopreservation involves vascular transplantation, which could theoretically counteract the latter phenomenon and markedly improve follicle survival. In theory, this technique should maintain endocrine and reproductive functions much longer than grafting of ovarian cortical fragments. However, this procedure includes a number of critical steps related to (A) the level of surgical expertise required to accomplish retrieval of a whole ovary with its vascular pedicle, (B) the choice of cryopreservation technique for freezing of the intact organ, and (C) successful execution of functional vascular reanastomosis upon thawing. The aim of this systematic review is to shed light on these challenges and summarize solutions that have been proposed so far in animal experiments and humans in the field of whole ovary cryopreservation and transplantation.

2. Methodology

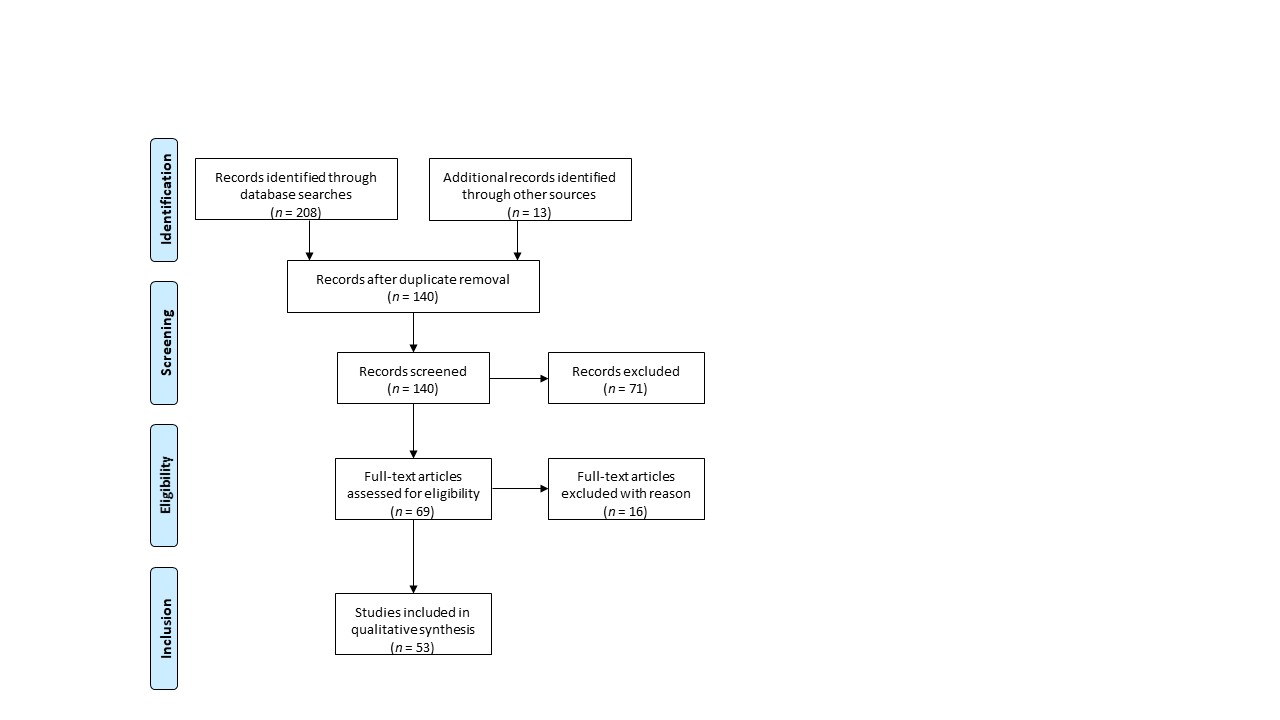

This systematic review was conducted according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines using the MEDLINE database (PubMed) [1] (Figure 1). The ffollollowing keywords were entered into the database: whole ovary, cryopreservation, transplantation. Out of 140 records, only peer-reviewed research articles focusing on the subject and written in English were taken into account for eligibility assessment (n = 69). Among studies performed on animal models, the following criteria led to the exclusion of 16 papers: (i) cryopreservation protocols for small animal models; (ii) transplantation of fresh whole ovaries; (iii) avascular transplantation. All studies using whole human ovaries were included, resulting in a total of 53 papers.

Figure 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart.

3. Challenges and Solutions

Although whole ovary cryopreservation and transplantation has yielded several live births in large animals [2][3][4], the technique involves a number of critical steps. The three main hurdles of whole ovary cryopreservation and transplantation are linked to (A) the surgical skills required to accomplish retrieval of a whole ovary with its vascular pedicle, (B) the cryopreservation technique adopted for freezing of the intact organ, and (C) successful execution of functional vascular reanastomosis upon thawing.

3.1. Whole ovary removal

In order to successfully harvest the entire ovary with its vascular pedicle for cryopreservation and future vascular reimplantation, great care must be taken when dissecting the ovarian vessels within the infundibulopelvic ligament. Indeed, the ovarian pedicle must be long enough (≥5 cm in humans) to allow processing of the graft and ensure perfect suture of donor vessels to recipient vessels of similar diameter [5][6]. Another crucial aspect is shortening the ischemic interval between ovary removal and cryopreservation as much as possible to avoid injury to ovarian cells [5][7][8][9]. For this reason, in the majority of studies, whole ovary removal is performed by laparotomy. However, some authors have demonstrated the feasibility of the procedure by laparoscopic surgery in sheep [10][11][12][13] and humans [5][14], despite the very twisted appearance of the ovarian vessels.

3.2. Freezing of a whole ovary

3.2.1. Freezing challenges

Developing a successful cryopreservation protocol for large organs like whole ovaries is extremely challenging [15]. Unfortunately, the success rate of freezing is inversely proportional to the complexity of the biological system being cryopreserved [16]. Numerous issues are associated with freezing and thawing of a whole ovary while preserving its viability upon thawing, including heat and mass transfer, poor heat transfer between the core and periphery of the organ, and adequate distribution of the cryoprotectant throughout the organ to prevent ice formation [17][18][19][20][21][22].

A preliminary in vitro study utilizing intact porcine ovaries demonstrated the beneficial effect of cryoprotectant use on the preservation of the ultrastructural integrity of primordial follicles [23]. Two further studies conducted on sheep ovaries underlined the protective impact of adding cryoprotectant to the freezing medium, compared to using a simple freezing medium composed of Ringer’s solution without any cryoprotective agents [24][25]. Wallin et al. (2009) used propanediol [24], while Milenkovic et al. (2011a) opted for dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as cryoprotectants [25]. Viability was assessed the same way in both studies and the results were similar. Briefly, the whole ovary was placed in a perfusion tray after thawing and stimulated with an adenylate cyclase stimulator (forskolin). Cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) and hormone levels were measured after stimulation and no significant difference was identified between groups with or without cryoprotectant. After perfusion, cells were isolated and cultured. Addition of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) to cell cultures resulted in higher progesterone levels in the group cryopreserved with cryoprotectant than the group cryopreserved without cryoprotectant. Histological assessment showed well preserved tissue architecture, with the presence of small follicles in all groups immediately after thawing. However, the ovarian architecture of ovaries frozen without cryoprotectant became disrupted, with signs of edema, disorganized stroma and shrunken follicles after perfusion, emphasizing the benefits of adding cryoprotectant to the freezing medium.

Optimal distribution of cryoprotectant throughout the organ and its vascular network is of paramount importance to avoid ice formation in intracellular and extracellular locations, particularly in blood vessels [18][26][27][28]. Intravascular ice formation irreversibly disrupts the endothelial cell layer, resulting in thrombotic events after transplantation of a frozen-thawed whole ovary [18][26][28][29][30][31]. Indeed, the large volume and complexity of a whole organ somewhat hamper cryoprotectant diffusion, making it difficult to obtain even distribution within the organ without inducing unacceptable levels of toxicity caused by high doses of cryoprotectant [19][32][33][34][35][36]. Gerritse et al. (2011) stressed the importance of associating perfusion of the ovarian pedicle with submersion of the bovine ovary using a cryoprotective solution to confer the highest degree of protection [37]. Another group investigated whether in vivo perfusion of the ovarian artery before removal of the ovine ovary could achieve optimal cryoprotectant distribution throughout the organ, but found that only 10% of the ovarian tissue was actually perfused. They concluded that perfusion should be performed in vitro, as described above [38].

Various studies have demonstrated a deleterious effect of both perfusion and cryopreservation on the ovarian vasculature, especially on the microvasculature within the ovarian medulla [18][24][34][39][40][41]. This could lead to capillary microthrombi arising from the ovarian medulla, remote from the anastomotic site, causing local ischemia. This process might be responsible for the poor follicle outcomes reported in several animal studies after vascular transplantation of whole ovaries, despite maintaining vascular patency of the anastomotic site [3][31][41]. An in vitro study performed with intact sheep ovaries demonstrated that cryopreservation significantly increased endothelial cell disruption and smooth muscle damage, but that adding the antiapoptotic agent sphingosine-1-phosphate to the cryopreservation medium (composed of 1.5 M DMSO) did not improve ovarian or vascular tissue viability following cryopreservation [42]. The authors concluded that cell loss was either due to necrosis caused by intracellular ice formation and osmotic stress, or that they might have targeted the wrong apoptotic pathway.

To further confirm that perfusion alone and perfusion associated with freezing have deleterious effects on endothelial cell function compared to unperfused fresh controls, the same team studied a number of endothelial cell-related genes in the medulla and the pedicle [41]. Like expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase, cryopreservation did not affect expression of endothelin-1 in the pedicle, but it was significantly downregulated in the medulla compared to perfusion alone. This suggests that small medullary vessels are more sensitive to the effects of cryopreservation, limiting their reactivity to vascular tone. On the other hand, expression of endothelin-2 was significantly upregulated in the pedicle after perfusion, suggesting that hypoxic conditions may have been created there during perfusion. However, since hypoxia stimulates endothelins, including endothelin-1 and -2, the authors could not explain why endothelin-1 did not follow the same pattern. Regarding cellular apoptosis, upregulation of proapoptotic Bcl-2-associated X protein (BAX) expression and downregulation of antiapoptotic Bcl-2 expression in response to perfusion and freezing suggested detrimental effects of both of these processes on cell survival. Interestingly, caspase-6 expression in the medulla was downregulated after perfusion, indicating that final execution of cell death may be suppressed within the medulla, despite potential upregulation of the apoptotic pathway by BAX, but the reason for this remains unknown. Expression of thrombospondin-1 was found to be downregulated in the medulla and pedicle after perfusion. According to the authors, downregulation of thrombospondin-1 expression may imply that wound repair mechanisms are recruited due to perfusion. They also concluded that both perfusion alone and in combination with freezing had a deleterious impact on endothelial cell function [41].

3.2.2. Freezing solutions

Considering all the issues involved in cryopreserving a whole organ, animal models used to investigate freezing protocols should have ovaries similar to humans in terms of size, architecture and ovulation patterns, with comparable follicle distribution within the cortex [35]. Porcine, ovine and bovine ovaries may be considered appropriate models [35][43], whose characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Three different freezing techniques have been developed over time: slow freezing, vitrification and directional freezing. The two main freezing procedures used for whole ovary cryopreservation are slow freezing and vitrification, but directional freezing is gaining ground thanks to recent encouraging results. The advantages/disadvantages of the three different ways of cryopreserving a whole ovary, are summarized in Table 2.

|

Species |

Ovarian volume (mean ± SD) |

Tissue architecture compared to the human ovary |

Ovulation pattern |

Cycle length (days) |

|

Human |

6.5 ± 2.9 cm3 [43] |

Not applicable |

Mono-ovulatory |

28-32 |

|

Cow |

14.3 ± 5.7 cm3 [35] |

Similar to human |

Mono-, diovulatory |

21 |

|

Pig |

7.3 ± 2.2 cm3 [35] |

Less fibrous |

Multi-ovulatory |

18-24 |

|

Sheep |

1.0 ± 0.4 cm3 [35] |

Similar to human |

Mono-, triovulatory |

16-17 (seasonal) |

|

|

Advantages |

Disadvantages |

|

Slow freezing |

Small amounts of cryoprotectant |

Prone to intracellular ice formation Non-uniform cooling gradient between the core and periphery |

|

Vitrification |

No crystallization, amorphous state of liquids |

Large amounts of cryoprotectant |

|

Directional freezing |

Controlled and uniform cooling gradient between the core and periphery |

New technique, very few studies reported in the literature |

3.3. Vascular transplantation of a whole ovary

3.3.1. Vascular transplantation challenges

Vascular transplantation of fresh whole ovaries has been largely successful in animal models (rats [44][45][46], rabbits [47][48][49][50][51][52][53][54][55], sheep [10][12][30][31][41][56][57][58][59][60][61][62], pigs [63][64], dogs [65] and monkeys [66][67]). Encouraging results have also been reported on transplantation of frozen-thawed whole ovaries in rats [29][68][69][70], rabbits [71] and sheep [2][3][4][11][12][13][30][31][41][72][73][74], which will be detailed further in this review. In humans, however, only fresh whole ovary transplantation has been undertaken so far [14][75][76][77], yielding one live birth to date [14].

For a successful outcome, vascular reanastomosis needs to be carried out by an experienced surgical team, including specialists in microvascular surgery, due to the level of complexity. Indeed, the reported diameter of the human ovarian artery is around 1 mm, and the ovarian vein approximately 1.2 mm [6]. Although the ovarian vein is slightly larger, its anastomosis may be more problematic because of its thin walls and poorly defined lumen [27].

Furthermore, selection of recipient vessels must be carefully considered to keep any vessel size discrepancy to a minimum, as sudden changes in vessel caliber cause turbulence to blood flow, which predisposes them to thrombosis [6][78][79]. Thrombosis is indeed the most common cause of anastomotic failure and is regulated by Virchow’s triad (damaged endothelial lining, hypercoagulability, turbulent blood flow).s the following plan: End-to-end vascular anastomosis is the most reliable approach, with an accuracy of 96%, and should be implemented when the vessel mismatch ratio is below 1:1.5 [6][78]. If the vessel mismatch ratio is above 1:1.5, a number of microsurgical techniques may be applied to manage donor versus recipient vessel discrepancy, such as oblique cutting, fish-mouth cutting, the sleeve technique or end-to-side anastomosis [6][78][80]. The goal is to achieve optimal blood flow through the connection and reduce the risk of thrombosis. In addition, sutureless methods like adhesives, laser welding or stents may also be considered depending on the surgeon’s experience [78][81][82]. Unfortunately, there is no consensus to date on the ideal technique to resolve the problem of vessel size mismatch [6][78][80]. Moreover, these complex anastomoses often lead to higher rates of complications, so the choice of a particular technique has to be made according to each individual case [6][78][80].

3.3.2. Vascular transplantation solutions

The Table 3 specifically focuses on reviewing vascular transplantation of frozen-thawed whole ovaries in animals, a technique only performed in rodents and sheep so far.

|

Species |

Reference |

Freezing procedure |

Transplantation |

Follow-up |

Outcomes of WOCT |

|

Rodents |

Rat: Wang et al. 2002b[68], Yin et al. 2003[69] |

Slow freezing |

Orthotopic, end-to-side (aorto-aortic and cava-caval) |

≥60 days |

§ 4/7 (57%) resumed estrous cycles after 12 ± 2.5 days § 1/7 (14.3%) conceived, but no live birth § Hormones (baseline vs. postgrafting): FSH ↗ (21.3 ± 6.2 vs. 9.1 ± 0.4; p<0.05); E2 ↘ (256.6 ± 61.8 vs. 416.9 ± 3.6; p<0.05) § Follicle counts (baseline vs. postgrafting): ↘ (p<0.01) |

|

Rabbit: Chen et al. 2006[71] |

Slow freezing |

Heterotopic (groin pocket), end-to-end (ovarian vessels to inferior epigastric vessels) |

6 months |

§ 10/12 (83.3%) resumed ovarian function after 1 week § No IVF attempts à no pregnancy § Hormones (baseline vs. postgrafting): FSH ↗ (1.8 ± 0.5 vs. 15.5 ± 3.6; p<0.01); P, E2 and LH = § Follicle counts (baseline vs. postgrafting): ↘ (18.68 ± 3.86 vs. 13.99 ± 3.21; p<0.0001) |

|

|

Rat: Qi et al. 2008[29] |

Slow freezing |

Orthotopic, end-to-side (aorto-aortic & cava-caval) |

≥42 days |

§ 8/10 (80%) resumed estrous cycles after 14 ± 3days § 2/10 (20%)conceived, but no live birth § Hormones (baseline vs. postgrafting): E2↘ (258 6 98 pmol/l vs. 434 6 98 pmol/l) § Follicle counts: not mentioned |

|

|

Rat: Ding et al. 2018b[70] |

Slow freezing |

Orthotopic, end-to-side (aorto-aortic & cava-caval)

|

8 months |

§ 5/25 (20%) died from early postoperative complications (infection/anastomotic thrombosis) § 14/20 (80%) resumed estrous cycles after 14 ± 3 days § 4/20 (20%) conceived, yielding healthy offspring + second and third generations of rats from the initial offspring § Hormones: FSH, P, E2, AMH = to sham-operated rats § Follicle counts: ↘ (p<0.05) |

|

|

Sheep |

Sheep: Bedaiwy et al. 2003[11] |

Slow freezing |

Heterotopic (rectus muscle), end-to-end (ovarian vessels to inferior epigastric vessels) |

8-10 days |

§ 11/11 (100%) immediate vascular patency § 3/11 (27%) maintained vascular patency after 8-10 days à 8/11 (73%) occluded vessels § Hormones (baseline vs. postgrafting): - Patent group: FSH = (182 ± 70.3 vs. 172 ± 42.0; p=0.84); E2 = (166 ± 50.0 vs. 163 ± 32.6; p=0.94) - Non-patent group: FSH ↗ (103 ± 89.7 vs. 268 ± 109; p=0.005); E2 = (199 ± 115 vs. 282 ± 132.0; p=0.25) § Follicle counts (patent vs. non-patent): ↘ (3.67 ± 2.08 vs. 0.250 ± 0.463; p=0.001) |

|

Sheep: Revel et al. 2004[74], Arav et al. 2005[72], 2010[73] |

Directional freezing |

Orthotopic, end-to-end (ovarian vessels to contralateral ovarian vessels) |

6 years |

§ 5/8 (62.5%) immediate vascular patency à 3/8 failure due to venous thrombosis (n=1), torn artery (n=1) and unknown reason (n=1) § 3/8 (37.5%) resumed P cyclicity 34 to 69 weeks after transplantation; 2/8 (25%): oocyte aspiration + embryo development up to the 8-cell stage § 2/8 (25%) maintained ovarian function for up to 3 years and 1/8 (12.5%) for up to 6 years § Hormones: not detailed § Follicle counts: not detailed |

|

|

Sheep: Imhof et al. 2006[3]

|

Slow freezing |

Orthotopic, end-to-end (ovarian vessels to contralateral ovarian vessels) |

18-19 months |

§ 6/8 (75%) long-term vascular patency § 4/8 (50%) resumed ovarian function 6 months after transplantation and P cyclicity resumed 12-14 months postgrafting § 1/8 (12.5%) spontaneous pregnancy yielding healthy offspring § Follicle survival rate: 1.7-7.6% |

|

|

Sheep: Bedaiwy and Falcone, 2007[12] |

Slow freezing |

Heterotopic (rectus muscle), ovarian vessels to inferior epigastric vessels |

8-10 days |

Successful vascular patency after 8-10 days: - 5/8 with end-to-end anastomosis (WOCT = 3/6; fresh = 2/2) - 2/6 with end-to-side anastomosis (WOCT = 1/4; fresh = 1/2) - 0/7 with fish-mouth anastomosis (WOCT = 0/5; fresh = 0/2) |

|

|

Sheep: Grazul-Bilska et al. 2008[13] |

Slow freezing |

Heterotopic (rectus muscle), end-to-end (ovarian vessels to inferior epigastric vessels) |

5 months |

§ 2/8 (25%) resumed ovarian function § No information on maintained vascular patency § 3 COCs obtained after FSH stimulation; 2 developed to metaphase II after in vitro maturation, but no fertilization § Hormones: only 2 ewes in whose ovarian function was restored were considered, no statistical analysis § Follicle counts: not mentionned |

|

|

Sheep: Courbière et al. 2009[30] |

Vitrification |

Orthotopic, end-to-end (ovarian vessels to contralateral ovarian vessels) |

12 months |

§ 1/5 (20%) long-term vascular patency à 4/5 failure due to lumbo-ovarian pedicle thrombosis (n=2), arterial thrombosis (n=1) and pneumopathy (n=1) (pedicle non-analyzable) § 1/5 (20%) resumed ovarian function 6 months after transplantation § Hormones: not detailed § Follicle counts: total follicle loss |

|

|

Sheep: Onions et al. 2009[31] |

Slow freezing |

Heterotopic (neck), end-to-side (aortic patch to carotid artery and ovarian vein to jugular vein) |

7 months |

§ 7/8 (87.5%) immediate and long-term vascular patency (! in 1 case = freezing device malfunction à excluded from further analysis) § 3/7 (42.9%) resumed ovarian cyclicity § Follicles (pregrafting vs. postgrafting): ↘ (36.7 ± 5.7 vs. 2.3 ± 1.0; p< 0.05) |

|

|

Sheep: Onions et al. 2013[41] |

Slow freezing |

Orthotopic, end-to-end (ovarian vessels to contralateral ovarian vessels) |

7 days |

§ 4/4 (100%) immediate vascular patency § 1/4 (25%) vascular patency at degrafting à 3/4 (75%): arterial thrombosis + FMS extravasation in the medulla § Follicle density (pregrafting vs. postgrafting): ↘ (0.42 vs. 0.02; p< 0.001) |

|

|

Sheep: Campbell et al. 2014[2] |

Slow freezing

|

Orthotopic, end-to-end (ovarian vessels to contralateral ovarian vessels) |

3 months |

§ 15/15 (100%) immediate vascular patency § 4/15 (27%) restored ovarian function within 7 weeks of transplantation § Follicle density within the functioning ovary (pregrafting vs. postgrafting): ↘ (2.48 ± 0.98 vs. 1.43 ± 0.10) |

|

|

Slow freezing |

Orthotopic, end-to-side (ovarian vessels to uterine vessels) |

11-23 months |

§ 14/14 (100%) immediate and long-term vascular patency § 14/14 (100%) restored ovarian function within 3 weeks of transplantation § 9/14 (64%) pregnancies + 4/14 (29%) and healthy live births. One offspring gave birth to second-generation lambs § Follicle survival rate: 60-70% |

||

|

Sheep: Torre et al. 2016[4] |

Slow freezing vs. Vitrification |

Orthotopic, end-to-end (ovarian vessels to contralateral ovarian vessels)

|

3 years |

§ 6/6 (100%) immediate vascular patency with slow freezing vs. 67% (4/6) with vitrification (1 death occurred in both groups) § 5/5 slow freezing + 6/6 vitrification (100%): restored hormone production § 1/5 (20%) pregnancy and live birth of healthy offspring in the slow-frozen group. No pregnancy in the vitrified group § Follicle survival rates (slow freezing vs. vitrication): 0.017% ± 0.019% vs. 0.3% ± 0.5% (p= 0.047) |

4. What has been done in humans so far?

4.1. Fresh whole ovary transplantation

To date, only a limited number of teams have attempted the exhausting and technically challenging feat of vascular transplantation of fresh whole ovaries in humans [14][75][76][77]. However, no attempts have yet been made to transplant a cryopreserved whole ovary in humans.

The first grafts of fresh whole ovaries were performed to the upper arm of the patient, and two teams reported successful heterotopic transplantation before initiating sterilizing pelvic irradiation [75][76]. In the first report, the patient was suffering from Hodgkin’s lymphoma. A cavity was created in her forearm by inserting a testicular prosthesis 2 months prior to transplantation in order to prepare the grafting site [75]. The ovary was then transplanted and the ovarian vessels were branched end-to-end to the vessels from the humeral vascular bundle. The authors reported no disruption to the menstrual cycle, which remained regular for up to two years, with evidence of follicle growth in the transplanted ovary [75]. In the second report, the patient was suffering from cervical carcinoma and heterotopic autotransplantation of the ovary to the upper arm was performed in the context of radical hysterectomy prior to pelvic radiotherapy [76]. For over a year, there was evidence of regular menstrual cycles and follicle growth upon clinical examination and ultrasound. Unfortunately, local disease recurred one year later and no long-term follow-up was reported.

A third team achieved the first successful orthotopic transplantation in a patient with Turner syndrome [77]. The transplant was retrieved from an immunologically matched donor sister through a Pfannenstiel incision. The ovarian vein was anastomosed end-to-side to the external iliac vein, and the ovarian artery was sutured end-to-end to the inferior epigastric artery by laparotomy. The ovary was fixed in its orthotopic position. Ovarian function resumed and was maintained for at least 2.5 years (follow-up duration). The patient also developed secondary sexual characteristics.

The last published study on fresh whole ovary transplantation was in 2008 between a pair of monozygotic twins discordant for POI [14]. The donor’s ovary was laparoscopically removed and transplanted to the recipient’s ovarian vessels through a minilaparotomy incision. This was actually the first report of a healthy live birth following orthotopic vascular transplantation of a fresh whole ovary in humans. These case reports provide proof of concept of the technical feasibility of the surgical procedure.

4.2. Whole ovary removal with a view to cryopreservation

Jadoul et al. (2007) demonstrated the feasibility of using a laparoscopic approach to harvest whole ovaries for further cryopreservation from nine patients [5]. This method maintains the minimally invasive nature of the procedure and should be the technique of choice for whole ovary cryopreservation. The authors stressed the importance of taking great care with dissection of the lumbo-ovarian ligament to ensure maximum length of the ovarian vessels (>5 cm), allowing dissection of the ovarian pedicle containing vessels of a suitable diameter (~1 mm), perfusion of the ovarian artery with cryoprotective solution, cryopreservation, and subsequent autotransplantation of the whole ovary. They also underlined the need to limit the interval between clamping of the ovarian pedicle and cryopreservation, in order to keep warm ischemia time as short as possible.

4.3. Cryopreservation of the human ovary

Few teams have had the opportunity to attempt cryopreservation of a whole human ovary (Table 4). Martinez-Madrid et al. (2004, 2007) were the first to report a successful slow-freezing protocol for human ovaries [83][84]. Although a significant decrease in the proportion of viable follicles (~30%) was observed after thawing, the authors did not detect any induction of apoptosis in any cell type, and no ultrastructural alterations were encountered.

Another team subsequently proposed a second protocol for slow freezing of the human ovary based on their results from cow ovaries [9]. In this protocol, the freezing medium used was the same, but the perfusion/submersion duration was 12 times longer than in Martinez-Madrid’s protocol. The authors obtained over 90% of morphologically normal follicles after thawing. Glucose uptake in cultured tissue fragments from cryopreserved ovaries reached 90-100% of that in fresh controls, and the endothelial lining appeared undamaged. However, no comparative study was conducted to identify the most adapted protocol.

Patrizio et al. (2007, 2008) were the first to describe successful cryopreservation of 11 human premenopausal ovaries using the directional freezing technique [85][86]. Their results were very encouraging, with no histological differences identified after thawing compared to fresh control ovaries.

The major issue when working with premenopausal whole human ovaries is their availability. In order to facilitate further research into development of an optimal freezing/thawing protocol, Milenkovic et al. (2011b) proposed using postmenopausal ovaries [87]. Indeed, this would initially allow us to establish and improve cryopreservation protocols respecting the vasculature and stromal architecture of the human ovary, since postmenopausal ovaries are free of follicles. These selected protocols could then be applied to precious premenopausal ovaries in order to study their impact on follicle populations. Indeed, the first step to clinical application is development of an optimal freezing/thawing protocol for the human ovary. Once this goal is met, we may potentially move towards transplantation experiments performed by experts in microsurgery.

|

Reference |

Number |

Freezing method |

Investigated outcomes |

|

Martinez-Madrid et al. 2004[83], 2007[84] |

3 |

Slow freezing |

Follicular, stromal and vascular viability, histological morphology, apoptosis, ultrastructural assessment |

|

Patrizio et al. 2007[85], 2008[86] |

11 |

Directional freezing |

Apoptosis, histological morphology |

|

Milenkovic et al. 2011b[87] |

10 (postmenopausal ovaries) |

Slow freezing |

Histological morphology, ultrastructural assessment, androgen production during in vitro perfusion |

|

Westphal et al. 2017[9] |

3 |

Slow freezing |

Follicular and vascular viability, histological morphology, glucose uptake during tissue fragment culture |

4.4. Recipient pedicle selection for vascular transplantation

Studies have investigated which recipient vessels should preferably be used to enhance the success rates of microvascular anastomosis. The choice of recipient pedicle should meet the following criteria [6][12]: (i) easy surgical accessibility of the pedicle; (ii) optimal vessel size match between recipient and donor ovarian vessels; (iii) possibility of postoperative ultrasound monitoring; and (iv) easy oocyte pick-up from the transplant for in vitro fertilization. To enable orthotopic reimplantation (in an intraperitoneal grafting site) of the whole organ, the deep circumflex iliac vessels and deep inferior epigastric vessels have been proposed as potential candidates [12]. Based on anatomical evaluation of these two pedicles in 14 human female cadavers, the deep circumflex iliac vessels appeared to provide the best ovarian vessel size match to ensure reliable end-to-end vascular anastomosis. In fact, there was an optimal size match between these two pedicles in 13 out of 14 female cadavers [6]. The deep inferior epigastric vessels, on the other hand, are subject to variations. Their caliber varies along their course and their diameter gradually decreases until they enter the muscle, making them unreliable for successful anastomosis [6]. A freshly dissected contralateral ovarian pedicle may also be used, as described by Silber et al. (2008) [14], but the ovarian artery has a highly tortuous appearance [6]. When heterotopic transplantation is planned, both the cutaneous mammary branches and the antecubital vessels appear to fulfill the above-mentioned criteria [12].

5. Limitations

There are two inherent risks in whole ovary cryopreservation and transplantation, the first being the all-or-nothing nature of the procedure. Indeed, if any calamity occurs during the intervention, it results in loss of all the follicles present in the ovary, as opposed to use of cortical strips, where several attempts can be made with the remaining frozen fragments. The greatest risks in this instance are cryopreservation issues and clot formation during autotransplantation. Although Campbell et al. (2014) recently demonstrated a very effective freezing procedure and anti-thrombotic strategy in sheep [2], protocols still need be adjusted to human beings.

The second crucial issue is the risk of malignant cell reimplantation [88][89][90]. While this threat also exists when transplanting frozen-thawed cortical strips, it is possible that the risk is higher when transplanting cryopreserved whole ovaries because the amount of grafted tissue is greater. An ovarian biopsy should therefore be frozen separately from the whole ovary in order to allow preimplantation analysis using extremely sensitive techniques and disease-specific markers, as done prior to cortical strip transplantation [91]. Among available techniques, histology and immunohistochemistry are sensitive enough to discern clusters of malignant cells, but isolated malignant cells may not be detected and potentially cause disease transmission upon transplantation [89][90][91]. Highly sensitive molecular biology techniques like RT-PCR are also used. They are able to identify small quantities of genetic material, whose sequences may correlate with known cancerous drifts. However, a positive result will only confirm the presence of malignant cells, but we still do not know how many malignant cells can actually cause disease recurrence [89][90][91]. Long-term xenografting experiments are nevertheless a valuable model to evaluate the risk of possible relapse. Xenotransplantation is usually performed in immunocompromised mice that serve as biological incubators, where potentially malignant cells within transplanted ovarian tissue are able to disseminate upon grafting. At degrafting, the transplants are subjected to the previously described sensitive tests and the animal is inspected for possible metastatic foci [89][90][91]. It is paramount for clinicians to bear in mind that ovarian biopsies used to perform all these tests cannot be transplanted to patients. Indeed, it is not possible to firmly rule out the presence of malignant cells in ovarian fragments that are transferred to patients.

If the risk of transmitting malignant cells is confirmed by preimplantation testing, one hypothetical option among others is use of the whole ovary as an ex vivo source of high-quality follicles [92][93]. Indeed, the whole ovary can be perfused in in vitro trays, and hormone stimulation and oocyte pick-up can then be performed ex vivo. In the early 1970s, researchers were able to maintain the premenopausal human ovary in perfusion for up to 8 hours and induce ovulation 4 to 5 hours after stimulation [94]. Later, rodent ovaries were perfused for up to 20 hours, allowing detailed studies into ovulation mechanisms and gonadotropin responses [95][96][97][98][99][100][101][102][103][104]. However, these periods are considerably shorter than those required to retrieve a sufficient number of mature oocytes upon ovarian stimulation in order to achieve reasonable live birth rates [105]. Pig and cow ovaries can be perfused for up to 2 days while maintaining low cellular apoptosis rates during culture [106][107], and researchers were recently able to extend the duration of whole organ culture to 4 days using fresh and frozen-thawed intact sheep ovaries [108]. Of course, further developments are required to accomplish entirely ex vivo ovarian stimulation with a view to in vitro fertilization.

6. Conclusions

Whole ovary cryopreservation has been proposed as an alternative method that could extend the longevity of ovarian transplants, since the entire follicle pool would be transplanted and ischemic damage to the grafted ovary would be largely avoided thanks to vascular anastomosis. This review summarizes the challenges of this technique and examines various solutions proposed in the literature over the past 20 years.

Recent studies in the field have yielded very encouraging results and research efforts must be sustained [2][9][108]. As the permeability of any vascular anastomosis is critical to the outcome, teams investigating whole ovary transplantation should include experts with microsurgical skills. Furthermore, underlying mechanisms leading to follicle loss after transplantation of cryopreserved whole ovaries, even when vascular patency is maintained, need to be elucidated in order to develop innocuous freezing and grafting protocols. Finally, cryopreservation protocols must be adapted to human ovaries. Given their scant availability, initial studies could be conducted with postmenopausal ovaries, as proposed by Milenkovic et al. (2011b) [87].

- Introduction

- Methodology

- Challenges & Solutions

- Whole Ovary Removal

- Freezing of a Whole Ovary

- Freezing Challenges

- Freezing Solutions

- Vascular Transplantation of a Whole Ovary

- Vascular Transplantation Challenges

- Vascular Transplantation Solutions

- What Has Been Done in Humans So Far?

-

- Fresh Whole Ovary Transplantation

- Whole Ovary Removal with a View to Cryopreservation

- Cryopreservation of the Human Ovary

- Recipient Pedicle Selection for Vascular Transplantation

-

- Limitations

- Conclusions