Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Rita Xu and Version 1 by Veridiana Maria Brianezi Dignani de Moura.

Prostate cancer (PC) is one of the main types of cancer that affects the male population worldwide. In recent decades, there has been a significant evolution in the methods of diagnosis and treatment, mainly due to the development of new research in the field of molecular biology, allowing for a better understanding of how this cancer develops and progresses from a genetic point of view.

- Immunobiology

- molecular biology

- oncogenes

1. Introduction

Cancer is considered a leading cause of death in humans before the age of 70 years in 112 of 183 countries, with a significant increase in incidence and mortality rates in recent years [1]. According to the Global Cancer Statistics (Globocan), prostate cancer is the third most frequent neoplastic entity, following breast and lung cancer [2]. It is the main neoplasm diagnosed in men in more than half of the countries in the world, with a high incidence in developed ones, with 1,414,259 cases being diagnosed worldwide in 2020, with 375,304 deaths [2,3][2][3].

Prostate cancer (PC) in dogs is a neoplasm of undifferentiated morphology—aggressive and with high rates of metastasis to regional lymph nodes, lungs, liver, and, mainly, bones [4]. Unlike humans, PC is commonly diagnosed in dogs at advanced stages, and patients have a short survival period and poor quality of life. This scenario has been justified by the ineffectiveness of androgen-dependent screening and diagnostic tests, such as growth factors, as well as the absence of effective treatment protocols [5].

Oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes have dominated the basic scientific research of tumorigenesis with recent advances in molecular biology, so that their evaluation and protein products may provide new diagnostic biological markers [6]. In addition, investigation and understanding of the molecular pathways of carcinogenesis involved in a prostate disease can add data to clinical information, helping to predict tumor progression at an early stage of cancer and identify new responsive therapeutic targets, as the treatment for PC in the canine species is still ineffective [7].

2. History and Epidemiological Aspects of Prostate Cancer

It is possible to identify that the first records of prostate cancer date from the 19th century. Based on scientific publications, in 1817, the English surgeon and pathologist George Langstaff described, for the first time, prostate cancer in men from an anatomo-macroscopic perspective [8]. His article published in the Medico-Chirurgical Transactions, entitled “Fungus Haematodes,” describes the case of a 68-year-old man with symptoms of abdominal pain and hematuria, besides urethral obstruction and prostate enlargement on rectal examination. However, only on autopsy did the pathologist confirm that it was a prostate neoformation extending into the urethra and bladder [8].

Other cases of PC were published in the scientific communities of Germany and France until the year 1850, but it was still considered by many an uncommon disease. However, in 1853, the physician J. Adams, an experienced microscopist at The London Hospital, described the first case of metastatic prostate cancer established by histopathological examination [9]. Then, researchers reviewed cases around the world for years, trying to better understand the prostate and its diseases. However, it was only at the turn of the last century, when Albarran and Halle [10] started histopathological evaluations of several samples of this gland, that malignant changes in the prostate tissue were really identified and recognized.

One of the milestones in understanding the pathology, epidemiology, and therapeutic aspects of prostate cancer occurred in 1896, when Reginald Harrison stated that this neoplasm was similar to hypertrophic lesions, in addition to having a higher incidence than was believed at that time [11]. This researcher had carried out, in 1884, one of the first surgical–therapeutic approaches aimed at prostate cancer [12], and his discoveries opened new paths for investigating the efficiency of other surgical methods, such as radical prostatectomy [13] and vasectomy [14].

Other studies seeking therapeutic alternatives were conducted still with conflicting results about surgical methods, such as the use of radioactive isotopes [15]. The response of sex hormones and their relationship with the prostate were also widely investigated at the same time that the canine species began to be used as one of the first experimental models for the study of prostatic diseases in men. In this context, initially in 1893, J. William White Jr. [16] observed that dog castration promoted the atrophy of glandular elements, followed by a reduction in the prostate volume. Despite this, it was only in 1939 that Huggins and collaborators [17,18][17][18] investigated the relationship between castration associated with estrogen administration and the blockade of prostatic secretions and cell atrophy in elderly dogs.

Around 80 years later, there has been a significant increase in the incidence and mortality by PC in men worldwide, affecting approximately 1.5 million patients [3]. Although variable, high prevalence has been observed in countries such as Australia and Japan, as well as in North America and Western Europe. However, the highest mortality numbers were identified in underdeveloped countries, such as some from Africa, and Central and South America. This scenario may be explained by some risk factors related to socioeconomic and racial aspects, although complex, aging-related risk factors, genetic factors such as BRAF mutation, race (black men are more predisposed), and limited access to diagnostic tests and therapeutic protocols could justify these differences [2,3][2][3].

Age is associated with higher occurrence and mortality rates, and men over 65 years of age are more susceptible to developing PC [19,20][19][20]. In a comprehensive review, Rawla [19] addresses risk factors associated with the development of prostate cancer in men, including racial and ethnic factors, as black and African-American men have the highest incidence and chances of developing PC earlier. Genetics, family history, type of diet, mineral and vitamin deficiencies, alcohol consumption, obesity, hyperglycemia, and environmental exposure to chemicals or radiation are also considered important risk factors for PC development [19].

Over time, dogs have still been considered the main experimental model to help understand the tumor biology of PC since the first study carried out using these animals in experiments, defining molecular bases and investigating new efficient therapeutic methods. Initial investigations in the 1900s report and describe morphologically the PC in dogs [21], proving that canine is the only mammalian species that spontaneously develops PC more often than man and exhibits similar histological characteristics that allow the assessment of tumor development and progression [22]. Furthermore, even in the face of alternatives, such as the use of transgenic mice and xenotransplantation [23], it is known that these models do not simulate the characteristics and complexity of the disease in humans [24].

The prevalence of spontaneous PC in dogs is low when compared to men, being recorded between 2–12% and varying significantly according to the adopted number of samples and experimental design [25]. Teske et al. [26] and Polisca et al. [25] evaluated canine prostate disorders in a large sample and found prostate tumors in 12.99 and 2.6% of cases, respectively. However, a retrospective analysis of canine PC revealed an incidence of less than 1% [27]. Moreover, the prevalence and mortality rate of PC in dogs is strongly related to increasing age, being more frequent in dogs over seven years old [26,27][26][27].

However, questions need to be clarified for the canine species, such as castration, an approach that is still questionable and widely discussed by the veterinary scientific community. Although castration has been considered for years to be the most appropriate therapeutic method for prostate disorders, the role of this approach as a risk factor for the development of canine PC has been studied in the last two decades [27]. According to researchers, adult and castrated male dogs are more likely to develop PC [25,26][25][26], whereas for others authors, the castration procedure does not reflect much on tumor progression or reduced chances of developing PC [28,29][28][29]. Despite efforts, there is still not enough evidence to support these theories, as experimental limitations prevent a consistent assessment, such as the size of the reference population, when the patient was castrated throughout life before the neoplasm was diagnosed. [27].

3. Preneoplastic Prostatic Lesions

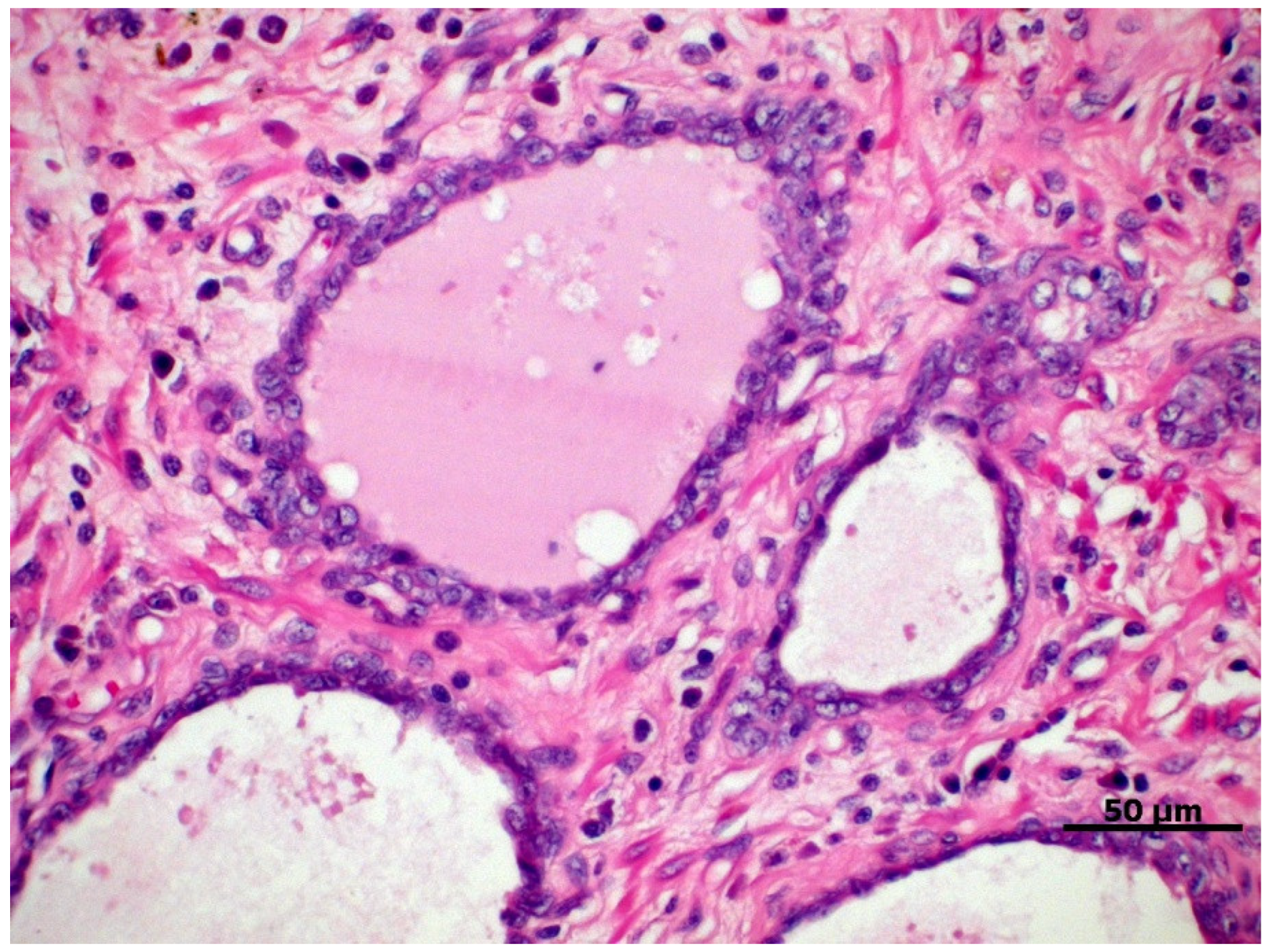

A couple of dysplastic lesions (Figure 1) are considered preneoplastic and have been studied for a better understanding of prostate carcinogenesis due to their potential for progression to PC, either because of their histomorphological similarity or because they exhibit potential carcinogenic molecular factors [30,31][30][31]. Two main lesions are recognized in the human prostate, that is, the proliferative inflammatory atrophy (PIA) and prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PIN), also described in the canine prostate [30,31][30][31].

Figure 1. Proliferative inflammatory atrophy in canine prostate, characterized by discrete proliferation of prostatic epithelium associated with mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate in the glandular interstitium. HE, 40×.

PIA is characterized by dysplastic, atrophic, and/or proliferative changes in the prostatic epithelium, associated with varying degrees of mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate in the glandular interstitium (Figure 1) [32]. In dogs, it is a commonly diagnosed prostate disorder often associated with prostatic hyperplasia, intraepithelial neoplasia, and PC, which can be found from the vicinity of the urethra to the pericapsular prostatic parenchyma of the medial portion of the prostate [31].

Lesions related to PIA in the canine species have a marked proliferative potential when compared to normal prostate tissue, with a higher population of intermediate cells. These findings suggest that this condition originates from the proliferation of basal cells stimulated by the continuous inflammatory process [33], corroborating the findings by Palmieri et al. [34], who report marked immunostaining of cytokeratin-5 (CK5) in many of the cuboidal luminal epithelial cells. These characteristics are phenotypically similar to some prostatic carcinomatous lesions in dogs, thus implying that most of these cases may have a similar origin [35].

Genotypically, changes related to p53 protein expression can be initially observed in PIA and accentuated in canine PC since the overexpression of this protein is associated with higher proliferative indices [36]. Furthermore, PIA samples also show down-regulation of phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), the androgen receptor gene, and its protein levels [33]. These changes in gene expression are important in prostate carcinogenesis, considering that the down-regulation of PTEN is involved in the activation of anti-apoptotic pathways and strongly correlated with loss of androgen receptors, a common event in PC [37,38][37][38].

PIN is considered the main precursor lesion of prostate cancer in men, mainly high-grade, and often diagnosed as a lesion adjacent to prostate adenocarcinoma [39,40][39][40]. On the other hand, PIN has a low occurrence in intact dogs and, when present, tends to present as a focal lesion [41]. Its actual incidence is still considered questionable and probably overestimated or not correctly diagnosed in many studies, besides its role in canine PC carcinogenesis still to be discussed [33].

The first reports of high-grade PIN in sexually intact dogs were published in the 1990s [42[42][43],43], in which cyto-histomorphological changes similar to those observed in the corresponding lesions in the human prostate are described. Morphologically, PIN shows foci of the proliferation of pre-existing ducts and acini with nuclear stratification and cell agglomeration, mild to moderate cell pleomorphism, anisokaryosis, and atypical basal cells [44].

However, under investigation, PIN characterization studies have been carried out to verify its potential in the carcinogenesis of canine PC. Despite exhibiting heterogeneous labeling for androgen receptors, basal cells in these lesions are believed to act in prostate tumor development with significant potential for proliferation [44]. Moreover, PIN exhibits an immunophenotype similar to PIA and canine PC with regard to cell cycle regulators [36], showing lower expression of TGF-β in epithelial cells and tissue stroma, referring to the impossibility of this cytokine to inhibit cell proliferation [45].

Palmieri et al. [46] suggested the role of heat shock protein 90 (HSP90), a chaperone protein, in canine prostate carcinogenesis and tumor progression and detected increased immunohistochemical labeling of this protein in PIA and PIN lesions, especially in the nuclear site. Assuming that HSP90 acts to promote essential metabolic pathways of tumorigenesis through its functions as a molecular chaperone protein, stimulating cell proliferation, its high expression in these lesions can be interpreted as an early and important event in the development of canine PC [47].

In fact, the detection of high-grade PIN in humans has clinical relevance, and its differentiation from other benign and intraductal lesions is still considered a challenge, mainly attributed to interobserver variability [48]. Thus, after high expression in cases of human PC being reported [49], the cyclin-dependent kinase 19 (CDK19) was identified as a specific and sensitive biomarker for the diagnosis of high-grade PIN, reflecting its involvement in the progression of neoplastic disease, as well as its malignant potential [50]. However, investigations of this molecule still need to be registered in canine prostate samples, and it is still necessary to identify and compare the signaling pathways that play an essential role in canine PIN development [51].

References

- World Health Organization. Global Health Estimates: Leading Causes of Death. Available online: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates/ghe-leading-causes-of-death (accessed on 3 October 2021).

- Globocan Prostate—Global Cancer Observatory. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/cancers/27-Prostate-fact-sheet.pdf (accessed on 3 October 2021).

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249.

- Laufer-Amorim, R.; Fonseca-Alves, C.E.; Villacis, R.A.R.; Linde, S.A.; Carvalho, M.; Larsen, S.J.; Marchi, F.A.; Rogatto, S.R. Comprehensive Genomic Profiling of Androgen-Receptor-Negative Canine Prostate Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1555.

- Christensen, B.W. Canine Prostate Disease. Vet. Clin. N. Am.-Small Anim. Pract. 2018, 48, 701–719.

- Kumar, B.; Rosenberg, A.Z.; Choi, S.M.; Fox-Talbot, K.; De Marzo, A.M.; Nonn, L.; Brennen, W.N.; Marchionni, L.; Halushka, M.K.; Lupold, S.E. Cell-type specific expression of oncogenic and tumor suppressive microRNAs in the human prostate and prostate cancer. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7189.

- Yang, G.; Goltsov, A.A.; Ren, C.; Kurosaka, S.; Edamura, K.; Logothetis, R.; DeMayo, F.J.; Troncoso, P.; Blando, J.; DiGiovanni, J.; et al. Caveolin-1 upregulation contributes to c-Myc-induced high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and prostate cancer. Mol. Cancer Res. 2012, 10, 218–229.

- Langstaff, G. Cases of fungus haematodes. Med. Chir Trans. 1817, 8, 272–314.

- Adams, J. The case of scirrhous of the prostate gland with corresponding affliction of the lymphatic glands in the lumbar region and in the pelvis. Lancet 1853, 1, 393.

- Albarran, J.; Halle, N. Hypertrophie et neoplasies epitheliales de la prostate. Compt. Rend. Soc. Biol. 1898, 4, 722.

- Harrison, R. Lecture on vesical stones and prostate disorders. Lancet 1896, 2, 1660.

- Harrison, R. Case where a scirrhous cancer of the prostate was removed transurethrally. Lancet 1884, 2, 483.

- Young, H.H. Four cases of radical prostatectomy. Johns Hopkins Bull. 1905, 16, 305.

- Albarran, J. La castration a 19angio neurectomie du cordon dans l’hypertrophie de la prostate. Press. Med. Paris 1897, 11, 274.

- Pastean, O. De l’emploi du radium dans leur traitemente des cancers de la prostate. J. Urol. Med. Chir. 1913, 4, 341.

- White, W.J. Surgical of the hypertrophied prostate. Ann. Surg. 1893, 152, 20.

- Huggins, C.; Masina, M.H.; Eichelberger, L.; Wharton, J.D. Quantitative studies of prostatic secretion. 1. Characteristics of the normal Secretion; the influence of thyroid, suprarenal, and testis extirpation and androgen substitution on the prostatic output. J. Exp. Med. 1939, 70, 543.

- Huggins, C.B.; Clark, P.J. Quantitative studies of prostatic secretion. 11. The effect of castration and of estrogen injection on the hyperplastic prostate glands of dogs. J. Exp. Med. 1940, 72, 747.

- Rawla, P. Epidemiology of Prostate Cancer. World J. Oncol. 2019, 10, 89.

- SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2013. Available online: https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2015 (accessed on 10 October 2021).

- Sticker, A. Uber den Krebs der Tiere, insbesondere uber die Empfanglichkeit der verschiedenen Haustierarten und iiber die Unterschiede des Tier- und Menschenkrebses. Arch. Klin. Chir 1902, 65, 1023–1087.

- Smith, J. Canine prostatic disease: A review of anatomy, pathology, diagnosis, and treatment. Theriogenology 2008, 70, 375–383.

- Jiang, Y.; Song, Q.; Cao, D.; Guo, H.; Shuangshuang, L. The Current Status of Prostate Cancer Animal Models. J. Vet. Med. Anim. Sci. 2020, 30, 1041.

- Hensley, P.J.; Kyprianou, N. Modeling Prostate Cancer in Mice: Limitations and Opportunities. J. Androl. 2012, 33, 144.

- Polisca, A.; Troisi, A.; Fontaine, E.; Menchetti, L.; Fontbonne, A. A retrospective study of canine prostatic diseases from 2002 to 2009 at the Alfort Veterinary College in France. Theriogenology 2016, 85, 835–840.

- Teske, E.; Naan, E.C.; van Dijk, E.M.; Van Garderen, E.; Schalken, J.A. Canine prostate carcinoma: Epidemiological evidence of an increased risk in castrated dogs. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2002, 197, 251–255.

- Schrank, M.; Romagnoli, S. Prostatic Neoplasia in the Intact and Castrated Dog: How Dangerous is Castration? Animal 2020, 10, 85.

- L’Eplattenier, H.F.; van Nimwegen, S.A.; Van Sluijs, F.J.; Kirpensteijn, J. Partial prostatectomy using Nd:YAG laser for management of canine prostate carcinoma. Vet. Surg. 2006, 35, 406–411.

- Shidaifat, F.; Gharaibeh, M.; Bani-Ismail, Z. Effect of castration on extracellular matrix remodeling and angiogenesis of the prostate gland. Endocr. J. 2007, 54, 521–529.

- De Marzo, A.M.; Platz, E.A.; Epstein, J.I.; Ali, T.; Billis, A.; Chan, T.Y.; Cheng, L.; Datta, M.; Egevad, L.; Ertoy-Baydar, D.; et al. A Working Group Classification of Focal Prostate Atrophy Lesions. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2006, 30, 1281–1291.

- Toledo, D.C.; Faleiro, M.B.R.; Rodrigues, M.M.P.; Di Santis, G.W.; Amorim, R.L.; Moura, V.M.B.D. Caracterização histomorfológica da atrofia inflamatória proliferativa na próstata canina. Cienc. Rural. 2010, 40, 1372–1377.

- De Marzo, A.; Marchi, V.L.; Epstein, J.I.; Nelson, W.G. Proliferative inflammatory atrophy of the prostate, Implications for prostatic carcinogenesis. Am. J. Pathol. 1999, 55, 1985–1992.

- Fernandes, G.G.; Pedrina, B.; Lainetti, P.F.; Kobayashi, P.E.; Al, E. Morphological and Molecular Characterization of Proliferative Inflammatory Atrophy in Canine Prostatic Samples. Cancers 2021, 13, 1887.

- Palmieri, C.; Story, M.; Lean, F.; Akter, S.; Grieco, V.; De Marzo, A. Diagnostic Utility of Cytokeratin-5 for the Identification of Proliferative Inflammatory Atrophy in the Canine Prostate. J. Comp. Pathol. 2018, 158, 1–5.

- Akter, S.H.; Lean, F.Z.; Lu, J.; Grieco, V.; Palmieri, C. Different Growth Patterns of Canine Prostatic Carcinoma Suggests Different Models of Tumor-Initiating Cells. Vet. Pathol. 2015, 52, 1027–1033.

- Faleiro, M.B.R.; Cintra, L.C.; Jesuino, R.S.A.; Damasceno, A.D.; Moura, V.M.B.D. Expression of cell cycle inhibitors in canine prostate with proliferative inflammatory atrophy and carcinoma. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zootec. 2018, 70, 82–92.

- Sun, C.; Dobi, A.; Mohamed, A. TMPRSS2-ERG fusion, a common genomic alteration in prostate cancer activates C-MYC and abrogates prostate epithelial differentiation. Oncogene 2008, 27, 5348–5353.

- Attard, G.; Swennenhuis, J.F.; Olmos, D.; Reid, A.H.M.; Vickers, E.; A’Hern, R.; Levink, R.; Coumans, F.; Moreira, J.; Riisnaes, R.; et al. Characterization of ERG, AR and PTEN Gene Status in Circulating Tumor Cells from Patients with Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 2912–2918.

- Bostwick, D.G.; Cheng, L. Precursors of prostate cancer. Histopathology 2012, 60, 4–27.

- De Marzo, A.M.; Haffner, M.C.; Lotan, T.L.; Yegnasubramanian, S.; Nelson, W.G. Premalignancy in Prostate Cancer: Rethinking What we Know. Cancer Prev. Res. 2016, 9, 648–656.

- Croce, G.B.; Rodrigues, M.M.P.; Faleiro, M.B.R.; Moura, V.M.B.D.; Laufer Amorim, R. Óxido nítrico, GSTP-1 e p53: Qual o papel desses biomarcadores nas lesões prostáticas do cão? Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zootec 2011, 63, 1368–1376.

- Waters, D.J.; Bostwick, D.G. Prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia occurs spontaneously in the canine prostate. J. Urol. 1997, 157, 713–716.

- Waters, D.J.; Hayden, D.W.; Bell, F.W.; Klausner, J.S.; Qian, J.; Bostwick, D.G. Prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia in dogs with spontaneous prostate cancer-PubMed. Prostate 1997, 30, 92–97.

- Matsuzaki, P.; Cogliati, B.; Sanches, D.; Chaible, L.; Kimura, K.; Silva, T.; Real-Lima, M.; Hernandez-Blazquez, F.; Laufer-Amorim, R.; Dagli, M. Immunohistochemical Characterization of Canine Prostatic Intraepithelial Neoplasia. J. Comp. Pathol. 2009, 142, 84–88.

- Toledo, D.C.; Faleiro, M.B.R.; Ferreira, H.H.; Faria, A.M.; Matos, M.P.C.; Laufer-Amorim, R.; Moura, V.M.B.D. Imunomarcação de TGF-β em próstatas caninas normais e com lesões proliferativas. Ciência Anim. Bras. 2019, 20, e-3453.

- Palmieri, C.; Mancini, M.; Benazzi, C.; Della Salda, L. Heat Shock Protein 90 is Associated with Hyperplasia and Neoplastic Transformation of Canine Prostatic Epithelial Cells. J. Comp. Path. 2014, 150, 393–398.

- Calderwood, S.K.; Gong, J. Heat Shock Proteins Promote Cancer: It’s a Protection Racket. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2016, 41, 311–323.

- Aldaoud, N.; Hallak, A.; Abdo, N.; Al Bashir, S.; Marji, N.; Graboski-Bauer, A. Interobserver Variability in the Diagnosis of High-Grade Prostatic Intraepithelial Neoplasia in a Tertiary Hospital in Northern Jordan. Clin. Pathol. 2020, 13, 1–14.

- Brägelmann, J.; Klümper, N.; Offermann, A.; von Mässenhausen, A.; Böhm, D.; Deng, M.; Queisser, A.; Sanders, C.; Syring, I.; Merseburger, A.S.; et al. Pan-Cancer Analysis of the Mediator Complex Transcriptome Identifies CDK19 and CDK8 as Therapeutic Targets in Advanced Prostate Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 23, 1829–1840.

- Offermann, A.; Joerg, V.; Hupe, M.C.; Becker, F.; Müller, M.; Brägelmann, J.; Kirfel, J.; Merseburger, A.S.; Sailer, V.; Tharun, L.; et al. CDK19 as a diagnostic marker for high-grade prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Hum. Pathol. 2021, 117, 60–67.

- Soylu, H.; Acar, N.; Ozbey, O.; Unal, B.; Koksal, I.T.; Bassorgun, I.; Ciftcioglu, A.; Ustunel, I. Characterization of Notch Signalling Pathway Members in Normal Prostate, Prostatic Intraepithelial Neoplasia (PIN) and Prostatic Adenocarcinoma. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2016, 22, 87–94.

More