Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Rachel Abbotts and Version 2 by Sirius Huang.

Epigenetics refers to heritable factors that influence cellular phenotypes other than DNA sequence, including DNA methylation, histone modification, and gene silencing by non-coding RNAs. Inhibitors of the first two of these mechanisms have been linked to the induction of BRCAness.

- BRCA mutations

- BRCAness

- epigenetic therapy

1. Introduction

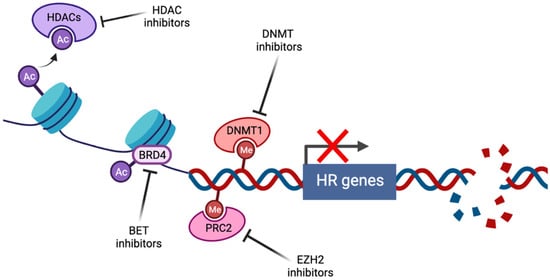

Figure 1 shows the induction of BRCAness by pharmacological targeting of epigenetic pathways. Histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACi) prevent the histone deacetylation activity of HDACs, thus maintaining chromatin in a condensed state associated with transcriptional repression. Bromodomain and extraterminal (BET) family members such as BRD4 act as transcriptional cofactors at acetylated gene promoters, including the homologous recombination (HR) genes RAD51 and BRCA1, whose expression is suppressed by BET inhibition. DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) and enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) inhibitors alter genome-wide methylation patterns and have been linked to altered DNA double strand break repair gene expression. In each case, repression of HR gene expression and activity has been described, contributing to induction of the BRCAness phenotype.

Figure 1. Induction of BRCAness by pharmacological targeting of epigenetic pathways (created with Biorender.com, accessed 15 May 2022).

2. Inhibition of DNA Methylation

DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) are critical mediators of epigenetic gene regulation, responsible for genome-wide de novo and maintenance methylation. Aberrations in methylation have been widely implicated in cancer development, progression, and response to treatment [1][2], and consequently, DNMT inhibitors (DNMTi) including decitabine and 5-azacytidine have been developed and are now FDA-approved for the treatment of myelodysplastic syndrome [3][4]. These agents are cytosine analogs that become incorporated into replicating DNA, where they are targeted for methylation by DNMTs. Due to their altered structure, they cannot be released by DNMT by β-elimination, leading to the covalent entrapment of DNMT into the DNA [5][6].

There is evidence of a biological interplay between DNMT1, the enzyme responsible for maintenance methylation, and PARP1, that provides a rationale for combination DNMTi-PARPi therapy. DNMT1 and PARP1 are members of a multiprotein complex that localizes to sites of oxidative DNA damage [7], where the presence of PARylated PARP1 inhibits methylation activity by DNMT1 [8], possibly to maintain an open chromatin structure to permit repair. It has been demonstrated that combining low-dose DNMTi treatment with the potent PARP-trapping PARPi talazoparib enhances PARP1-DNA binding, synergistically enhancing cytotoxicity across a number of BRCA-wildtype cancer types with minimal toxicity in in vivo models [9][10][11] or human subjects [12][13]. Similar synergism has also been observed when talazoparib is combined with the second-generation DNMTi guadecitabine [14].

In addition to a direct reduction in the free enzyme pool, DNMT entrapment also induces ubiquitin-E3 ligase-mediated proteasomal degradation of free DNMT1 [15][16]. Accordingly, low doses of DNMTi are sufficient to alter methylation patterns across the genome, leading to widespread alterations in multiple molecular pathways including the DNA damage response (DDR) and apoptosis [17]. Among the myriad of pathways contributing to the Hanahan and Weinberg ‘hallmarks of cancer’ [18] that are altered by DNMTi, a recent examination of the DNA repair reactome in non-small cell lung [10], breast, and ovarian cancers [11] demonstrated a significant reduction in DSB repair, particularly involving the FA pathway. Of note was the downregulation of FANCD2, which is mono-ubiquitinated by other FA pathway members in response to DNA damage, leading to colocalization with BRCA1 and BRCA2 during homologous recombination repair of DSBs, and resulting in it being ascribed a role as a BRCAness gene [19]. Furthermore, FANCD2 monoubiquitination is required for interactions with FANCD2/FANCI-associated nuclease 1 (FAN1), which mediates the canonical FA roles of interstrand crosslink repair and the resolution of stalled replication forks, potentially including those induced by trapped PARP1 and/or DNMT1 [20]. In keeping with the loss of these repair roles, DNMTi-induced FANCD2 downregulation was associated with a BRCAness phenotype, including increased replication fork stalling, DSB accumulation as measured by γH2AX foci accumulation, and a reduction in RAD51-mediated DSB repair capacity. Accordingly, in several human cancer cell lines and murine xenograft models, combining a low dose DNMTi with the PARPi talazoparib produces a significant and synergistic increase in tumor cell cytotoxicity [10][11]. These results have led to a dose-finding Phase 1 trial in untreated or relapsed/refractory AML using DNMTi decitabine and PARPi talazoparib [21], and a Phase 1 trial in BRCA-proficient breast cancer treated using oral decitabine and talazoparib (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical trials evaluating epigenetic therapy in combination with PARPi.

| ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier [22] (accessed 20 May 2022) |

Phase | Epigenetic Drug | PARPi | Other Drugs | Cancer | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNMT inhibitor | ||||||

| NCT02878785 | I/II | Decitabine | Talazoparib | Untreated or R/R 1 acute myeloid leukemia (AML) | Active, not recruiting | |

| HDAC inhibitor | ||||||

| NCT03259503 | I | Vorinostat | Olaparib | Gemcitabine, busulphan, melphalan | R/R lymphoma undergoing stem cell transplant | Recruiting |

| NCT03742245 | I | Vorinostat | Olaparib | R/R or metastatic breast | Recruiting | |

| EZH2 inhibitor | ||||||

| NCT04355858 | II | SHR2554 | SHR3162 | Luminal advanced breast | Recruiting |

1 R/R = relapsed/refractory.

DNMTi-induced reversal of cancer-associated methylation abnormalities can reactivate abnormally methylated tumor suppressor gene promoters. One emerging example is Schlafen 11 (SLFN11), which irreversibly inhibits replication in cells undergoing replication stress such as DNA-damaging chemotherapy [23]. High levels of SLFN11 destabilizes the interaction between single-stranded DNA and replication protein A (RPA) at the sites of DNA damage, inhibiting downstream DSB repair and producing cell cycle checkpoint activation [24]. The suppression of SLFN11 expression is observed in ~50% of cancer cell lines and is correlated with a resistance to DNA-damaging agents including PARP inhibitors [25]. SLFN11 suppression appears to be primarily epigenetic in origin, linked to promoter methylation, histone deacetylation, and PRC-mediated histone methylation [23]. Decitabine can reverse SLFN11 promoter methylation, leading to the re-expression and re-sensitization to DNA-damaging agents, and similar results have also been observed following EZH2 [26] or HDAC inhibitors [27] (see below), providing a further rationale for future studies combining epigenetic agents with PARP inhibitors.

3. Maintenance of Chromatin Repressive States

Histone deacetylases (HDACs) remove acetyl groups from ϵ-N-acetyl lysine residues on histones, leading to chromatin condensation and transcriptional repression. Abnormal acetylation resulting from HDAC overexpression can downregulate the expression of various tumor suppressive mechanisms, including cyclin-dependent kinases, differentiation factors, and proapoptotic signals, leading to the uncontrolled proliferation, de-differentiation, and survival that is characteristic of oncogenesis and metastasis [28]. The eighteen identified members of the HDAC family have been classified into four groups (class I, IIa/b, V, and III/sirtuins) based on homology to yeast HDACs. Compounds with anti-HDAC activity are numerous, and can be divided into pan-HDAC inhibitors (HDACi), which exhibit activity against all non-sirtuin HDACs, or selective HDACi, which target specific HDACs [29]. FDA approval has been granted for the treatment of various hematological malignancies for three pan-HDACi (vorinostat, belinostat, and panobinostat) and one HDAC1/2-selective HDACi (romidepsin) [30].

Acetylation exerts effects over the chromatin structure that impacts the recognition and repair of DNA damage [31], and accordingly, HDACi have been reported to alter DSB repair capacity [32]. While deacetylation activity of HDAC1/2 has been shown to both directly and indirectly decrease c-NHEJ activity [33][34], the role of HDACs in HR, and hence the therapeutic potential of HDACi for the induction of BRCAness, is less clearly defined. Of note, HR proteins including BRCA1, BRCA2, and RAD51 have been reported to be suppressed by HDACi in a variety of cancers [35][36], sensitizing to PARPi [37][38][39][40][41][42][43]. Based on these results, phase I trials combining olaparib with vorinostat are underway in advanced lymphoma and breast cancer (Table 1).

Notably, the inhibition of the deacetylation activity following HDACi exposure leads to PARP1 hyperacetylation and enrichment in chromatin that resembles PARPi-induced PARP trapping. When combined with PARPi, HDACi treatment further increases PARP trapping, synergistically sensitizing to the PARP-trapping PARPi talazoparib [44]. Synergism has also been observed when HDACi are combined with DNMTi, specifically by enhancing the re-expression of genes silenced by abnormal promoter methylation [12][45]. Valdez et al. have reported synergistic inhibition of AML and lymphoma cell proliferation by the triple combination of PARPi niraparib, DNMTi decitabine, and HDACi romidepsin or pabinostat, associated with the activation of ATM-mediated DDR, increased ROS production, and the induction of apoptosis [46]. These effects were hypothesized to be the sequelae of DSB accumulation induced by triple combination through three mechanisms: significantly enhanced PARP trapping; acetylation and inhibition of DNA repair proteins including Ku70/80 and PARP1; and the downregulation of the nucleosome-remodeling deacetylase complex, a transcriptional repressor with chromatin remodeling activity that is functionally linked to efficient DNA repair [47]. While further preclinical study is required, these results provide a rationale for the future development of combination therapy using PARPi, HDACi, and DNMTi.

4. Polycomb Repressive Complex 2

An enhancer of the zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) is the histone methyltransferase subunit of polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2), which methylates histone H3 on lysine 27 (H3K27me3) to mark chromatin as transcriptionally silent. PRC2 plays an important oncogenic role through the modulation of the DDR [48]. EZH2 overexpression, which is common in many cancers [49], induces the downregulation of RAD51 homolog expression [50], cytoplasmic BRCA1 retention [51], and impaired HR that is associated with increased genomic instability. PRC2 appears to play a role in the DSB repair pathway choice, being recruited to DSBs in a Ku-dependent mechanism to promote efficient NHEJ [52], and accordingly, EZH2 depletion favors HR, impairs NHEJ, and sensitizes to irradiation damage [53]. Recent evidence indicates that this DSB repair pathway switch can be therapeutically targeted by PARPi in a subset of HR-proficient tumors overexpressing the oncogene coactivator-associated arginine methyltransferase 1 (CARM1). The overexpression of CARM1 promotes the EZH2 silencing of MAD2L2, a member of the shieldin complex that limits DNA end resection to favor NHEJ. Accordingly, in CARM1-high cells, EZH2 inhibition upregulates MAD2L2, increasing error-prone NHEJ activity and associated chromosomal abnormalities, and producing mitotic catastrophe in combination with PARPi treatment [54]. An ongoing phase II clinical trial, evaluating multiple targeted therapies in a biomarker-guided precision therapy approach, includes the novel agents SHR2554 (EZH2 inhibitor) and SHR3162 (PARPi) (Table 1).

5. BET Proteins

The conserved bromodomain and extraterminal (BET) family of proteins are characterized by two tandem bromodomains that bind to activated lysine residues on target proteins [55][56]. BET members preferentially interact with hyperacetylated histones, leading to an accumulation at the transcriptionally active regulatory elements [57]. BET family member BRD4 acts as a transcriptional cofactor, influencing the expression of a wide range of genes involved in cell fate determination. In cancer, BRD4 has been implicated in the activation of a multitude of oncogenes, co-occupying a set of promoter super-enhancers associated with prominent oncogenic drivers such as c-MYC [58][59]. High affinity small molecules targeting the BET bromodomains demonstrate preclinical efficacy in a wide range of cancers associated with transcriptional suppression of key proto-oncogenes including c-MYC, N-MYC, FOSL1, and BLC2 (reviewed in [57].

The first report of potential synergism between BET inhibition and PARPi was based on a drug combination screen testing PARPi olaparib in BRCA-wildtype triple negative breast (TNBC), ovarian, and prostate cancer in combination with 20 well-characterized epigenetic modulators across seven classes, demonstrating synergism for all tested BET inhibitors (BETi) [60]. BETi treatment significantly enhanced PARPi-induced DSB accumulation independent of PARP-trapping, associated with the repression of BRCA1 and RAD51 transcription, which is suggestive of induced BRCAness. Notably, BETi treatment could disrupt the enrichment of BRD2/3/4 at the BRCA1 and RAD51 promoter regions, in addition to the putative super-enhancer region downstream of the BRCA1 promoter that exerted a stronger transcriptional enhancing activity than the promoter region alone [60]. Validation of these results, with similar BETi-induced repression of BRCA1 and RAD51, induction of an HR defect, and sensitivity to PARPi, has since been reported in TNBC [61].

A subsequent study used publicly available transcriptional profiling data to demonstrate that BRD4 inhibition modulates a previously validated HR defect gene signature [62], though finding minimal impact on BRCA1 or RAD51 expression in cell lines of multiple cancer types. Instead, a consistent and marked downregulation of CtIP was observed, in keeping with ChIP-seq analysis that indicates that both the CtIP promoter and an associated enhancer region are directly targeted by BRD4. BETi induced PARPi sensitivity in 40 of 55 cancer cell lines and five in vivo models spanning breast, ovarian, and pancreatic cancer, as well as resensitizing PARPi-resistant cells [63]. Despite the mechanistic discrepancies between the studies, these results indicate the therapeutic potential of the PARPi-BETi combination that warrants further investigation.

References

- Issa, J.-P.J.; Kantarjian, H.M. Targeting DNA Methylation. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 3938–3946.

- Baylin, S.B.; Jones, P.A. A decade of exploring the cancer epigenome—Biological and translational implications. Nat. Cancer 2011, 11, 726–734.

- Issa, J.-P.J.; Garcia-Manero, G.; Giles, F.J.; Mannari, R.; Thomas, D.; Faderl, S.; Bayar, E.; Lyons, J.; Rosenfeld, C.S.; Cortes, J.; et al. Phase 1 study of low-dose prolonged exposure schedules of the hypomethylating agent 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (decitabine) in hematopoietic malignancies. Blood 2004, 103, 1635–1640.

- Kantarjian, H.; Issa, J.P.; Rosenfeld, C.S.; Bennett, J.M.; Albitar, M.; DiPersio, J. Decitabine Improves Patient Outcomes in Myelodysplastic Syndromes: Results of a Phase III Randomized Study. Cancer 2006, 106, 1794–1803.

- Gnyszka, A.; Jastrzebski, Z.; Flis, S. DNA methyltransferase inhibitors and their emerging role in epigenetic therapy of cancer. Anticancer Res. 2013, 33, 2989–2996.

- Öz, S.; Raddatz, G.; Rius, M.; Blagitko-Dorfs, N.; Lübbert, M.; Maercker, C.; Lyko, F. Quantitative Determination of Decitabine Incorporation Into DNA and Its Effect on Mutation Rates in Human Cancer Cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, e152.

- O’Hagan, H.; Wang, W.; Sen, S.; Shields, C.D.; Lee, S.; Zhang, Y.W.; Clements, E.G.; Cai, Y.; Van Neste, L.; Easwaran, H.; et al. Oxidative Damage Targets Complexes Containing DNA Methyltransferases, SIRT1, and Polycomb Members to Promoter CpG Islands. Cancer Cell 2011, 20, 606–619.

- Caiafa, P.; Guastafierro, T.; Zampieri, M. Epigenetics: Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of PARP-1 regulates genomic methylation patterns. FASEB J. 2008, 23, 672–678.

- Muvarak, N.E.; Chowdhury, K.; Xia, L.; Robert, C.; Choi, E.Y.; Cai, Y. Enhancing the Cytotoxic Effects of PARP Inhibitors with DNA Demethylating Agents-A Potential Therapy for Cancer. Cancer Cell 2016, 30, 637–650.

- Abbotts, R.; Topper, M.J.; Biondi, C.; Fontaine, D.; Goswami, R.; Stojanovic, L.; Choi, E.Y.; McLaughlin, L.; Kogan, A.A.; Xia, L.; et al. DNA methyltransferase inhibitors induce a BRCAness phenotype that sensitizes NSCLC to PARP inhibitor and ionizing radiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 22609–22618.

- McLaughlin, L.J.; Stojanovic, L.; Kogan, A.A.; Rutherford, J.L.; Choi, E.Y.; Yen, R.-W.C.; Xia, L.; Zou, Y.; Lapidus, R.G.; Baylin, S.B.; et al. Pharmacologic induction of innate immune signaling directly drives homologous recombination deficiency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 17785–17795.

- Topper, M.J.; Vaz, M.; Chiappinelli, K.B.; Shields, C.E.D.; Niknafs, N.; Yen, R.-W.C.; Wenzel, A.; Hicks, J.; Ballew, M.; Stone, M.; et al. Epigenetic Therapy Ties MYC Depletion to Reversing Immune Evasion and Treating Lung Cancer. Cell 2017, 171, 1284–1300.e21.

- Chiappinelli, K.B.; Strissel, P.L.; Desrichard, A.; Li, H.; Henke, C.; Akman, B.; Hein, A.; Rote, N.S.; Cope, L.M.; Snyder, A.; et al. Inhibiting DNA Methylation Causes an Interferon Response in Cancer via dsRNA Including Endogenous Retroviruses. Cell 2015, 162, 974–986.

- Pulliam, N.; Fang, F.; Ozes, A.R.; Tang, J.; Adewuyi, A.; Keer, H.; Lyons, J.; Baylin, S.B.; Matei, D.; Nakshatri, H.; et al. An Effective Epigenetic-PARP Inhibitor Combination Therapy for Breast and Ovarian Cancers Independent of BRCA Mutations. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 3163–3175.

- Ghoshal, K.; Datta, J.; Majumder, S.; Bai, S.; Kutay, H.; Motiwala, T.; Jacob, S.T. 5-Aza-Deoxycytidine Induces Selective Degradation of DNA Methyltransferase 1 by a Proteasomal Pathway That Requires the KEN Box, Bromo-Adjacent Homology Domain, and Nuclear Localization Signal. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005, 25, 4727–4741.

- Patel, K.; Dickson, J.; Din, S.; Macleod, K.; Jodrell, D.; Ramsahoye, B. Targeting of 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine residues by chromatin-associated DNMT1 induces proteasomal degradation of the free enzyme. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, 4313–4324.

- Tsai, H.-C.; Li, H.; Van Neste, L.; Cai, Y.; Robert, C.; Rassool, F.V.; Shin, J.J.; Harbom, K.M.; Beaty, R.; Pappou, E.; et al. Transient Low Doses of DNA-Demethylating Agents Exert Durable Antitumor Effects on Hematological and Epithelial Tumor Cells. Cancer Cell 2012, 21, 430–446.

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674.

- Bogliolo, M.; Surrallés, J. The Fanconi Anemia/BRCA Pathway: FANCD2 at the Crossroad between Repair and Checkpoint Responses to DNA Damage. In Madame Curie Bioscience Database ; Landes Bioscience: Austin, TX, USA, 2013.

- Yoshikiyo, K.; Kratz, K.; Hirota, K.; Nishihara, K.; Takata, M.; Kurumizaka, H. KIAA1018/FAN1 Nuclease Protects Cells against Genomic Instability Induced by Interstrand Cross-Linking Agents. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 21553–21557.

- Baer, M.R.; Kogan, A.A.; Bentzen, S.M.; Mi, T.; Lapidus, R.G.; Duong, V.H.; Emadi, A.; Niyongere, S.; O’Connell, C.L.; Youngblood, B.A.; et al. Phase I clinical trial of DNA methyltransferase inhibitor decitabine and PARP inhibitor talazoparib combination therapy in relapsed/refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 1313–1322.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Available online: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- Murai, J.; Thomas, A.; Miettinen, M.; Pommier, Y. Schlafen 11 (SLFN11), a restriction factor for replicative stress induced by DNA-targeting anti-cancer therapies. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 201, 94–102.

- Mu, Y.; Lou, J.; Srivastava, M.; Zhao, B.; Feng, X.; Liu, T.; Chen, J.; Huang, J. SLFN 11 inhibits checkpoint maintenance and homologous recombination repair. EMBO Rep. 2015, 17, 94–109.

- Lok, B.H.; Gardner, E.E.; Schneeberger, V.E.; Ni, A.; Desmeules, P.; Rekhtman, N.; De Stanchina, E.; Teicher, B.A.; Riaz, N.; Powell, S.N.; et al. PARP Inhibitor Activity Correlates with SLFN11 Expression and Demonstrates Synergy with Temozolomide in Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 523–535.

- Gardner, E.; Lok, B.; Schneeberger, V.E.; Desmeules, P.; Miles, L.; Arnold, P.; Ni, A.; Khodos, I.; De Stanchina, E.; Nguyen, T.; et al. Chemosensitive Relapse in Small Cell Lung Cancer Proceeds through an EZH2-SLFN11 Axis. Cancer Cell 2017, 31, 286–299.

- Tang, S.-W.; Thomas, A.; Murai, J.; Trepel, J.B.; Bates, S.E.; Rajapakse, V.N.; Pommier, Y. Overcoming Resistance to DNA-Targeted Agents by Epigenetic Activation of Schlafen 11 (SLFN11) Expression with Class I Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 1944–1953.

- Glozak, M.A.; Seto, E. Histone Deacetylases and Cancer. Oncogene 2007, 26, 5420–5432.

- Hontecillas-Prieto, L.; Flores-Campos, R.; Silver, A.; De Álava, E.; Hajji, N.; García-Domínguez, D.J. Synergistic Enhancement of Cancer Therapy Using HDAC Inhibitors: Opportunity for Clinical Trials. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 1113.

- Ho, T.C.S.; Chan, A.H.Y.; Ganesan, A. Thirty Years of HDAC Inhibitors: 2020 Insight and Hindsight. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 12460–12484.

- Misteli, T.; Soutoglou, E. The emerging role of nuclear architecture in DNA repair and genome maintenance. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 243–254.

- Koprinarova, M.; Botev, P.; Russev, G. Histone deacetylase inhibitor sodium butyrate enhances cellular radiosensitivity by inhibiting both DNA nonhomologous end joining and homologous recombination. DNA Repair 2011, 10, 970–977.

- Miller, K.M.; Tjeertes, J.V.; Coates, J.; Legube, G.; Polo, S.E.; Britton, S.; Jackson, S.P. Human HDAC1 and HDAC2 function in the DNA-damage response to promote DNA nonhomologous end-joining. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010, 17, 1144–1151.

- Mladenov, E.; Iliakis, G. Induction and repair of DNA double strand breaks: The increasing spectrum of non-homologous end joining pathways. Mutat. Res. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 2011, 711, 61–72.

- Ladd, B.; Ackroyd, J.J.; Hicks, J.K.; Canman, C.E.; Flanagan, S.A.; Shewach, D.S. Inhibition of homologous recombination with vorinostat synergistically enhances ganciclovir cytotoxicity. DNA Repair 2013, 12, 1114–1121.

- Xiao, W.; Graham, P.H.; Hao, J.; Chang, L.; Ni, J.; Power, C.A.; Dong, Q.; Kearsley, J.H.; Li, Y. Combination Therapy with the Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor LBH589 and Radiation Is an Effective Regimen for Prostate Cancer Cells. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e74253.

- Ha, K.; Fiskus, W.; Choi, D.S.; Bhaskara, S.; Cerchietti, L.; Devaraj, S.G.T.; Shah, B.; Sharma, S.; Chang, J.C.; Melnick, A.M.; et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitor treatment induces ‘BRCAness’ and synergistic lethality with PARP inhibitor and cisplatin against human triple negative breast cancer cells. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 5637–5650.

- Wiegmans, A.P.; Yap, P.-Y.; Ward, A.; Lim, Y.C.; Khanna, K.K. Differences in Expression of Key DNA Damage Repair Genes after Epigenetic-Induced BRCAness Dictate Synthetic Lethality with PARP1 Inhibition. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2015, 14, 2321–2331.

- Yin, L.; Liu, Y.; Peng, Y.; Peng, Y.; Yu, X.; Gao, Y. PARP Inhibitor Veliparib and HDAC Inhibitor SAHA Synergistically Co-Target the UHRF1/BRCA1 DNA Damage Repair Complex in Prostate Cancer Cells. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. CR 2018, 37, 153.

- Baldan, F.; Mio, C.; Allegri, L.; Puppin, C.; Russo, D.; Filetti, S.; Damante, G. Synergy between HDAC and PARP Inhibitors on Proliferation of a Human Anaplastic Thyroid Cancer-Derived Cell Line. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2015, 2015, 978371.

- Liang, B.Y.; Xiong, M.; Ji, G.B.; Zhang, E.L.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Dong, K.S. Synergistic Suppressive Effect of PARP-1 Inhibitor PJ34 and HDAC Inhibitor SAHA on Proliferation of Liver Cancer Cells. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 35, 535–540.

- Hegde, M.; Mantelingu, K.; Pandey, M.; Pavankumar, C.S.; Rangappa, K.S.; Raghavan, S.C. Combinatorial Study of a Novel Poly (ADP-ribose) Polymerase Inhibitor and an HDAC Inhibitor, SAHA, in Leukemic Cell Lines. Target. Oncol. 2016, 11, 655–665.

- Rasmussen, R.D.; Gajjar, M.K.; Jensen, K.E.; Hamerlik, P. Enhanced efficacy of combined HDAC and PARP targeting in glioblastoma. Mol. Oncol. 2016, 10, 751–763.

- Robert, C.; Nagaria, P.K.; Pawar, N.; Adewuyi, A.; Gojo, I.; Meyers, D.J.; Cole, P.A.; Rassool, F.V. Histone deacetylase inhibitors decrease NHEJ both by acetylation of repair factors and trapping of PARP1 at DNA double-strand breaks in chromatin. Leuk. Res. 2016, 45, 14–23.

- Cameron, E.E.; Bachman, K.E.; Myöhänen, S.; Herman, J.G.; Baylin, S.B. Synergy of demethylation and histone deacetylase inhibition in the re-expression of genes silenced in cancer. Nat. Genet. 1999, 21, 103–107.

- Valdez, B.C.; Li, Y.; Murray, D.; Liu, Y.; Nieto, Y.; Champlin, R.E.; Andersson, B.S. Combination of a hypomethylating agent and inhibitors of PARP and HDAC traps PARP1 and DNMT1 to chromatin, acetylates DNA repair proteins, down-regulates NuRD and induces apoptosis in human leukemia and lymphoma cells. Oncotarget 2017, 9, 3908–3921.

- Li, D.-Q.; Kumar, R. Mi-2/NuRD Complex Making Inroads Into DNA-damage Response Pathway. Cell Cycle 2010, 9, 2071–2079.

- Veneti, Z.; Gkouskou, K.K.; Eliopoulos, A. Polycomb Repressor Complex 2 in Genomic Instability and Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1657.

- Yamaguchi, H.; Hung, M.-C. Regulation and Role of EZH2 in Cancer. Cancer Res. Treat. 2014, 46, 209–222.

- Zeidler, M.; Varambally, S.; Cao, Q.; Chinnaiyan, A.M.; Ferguson, D.O.; Merajver, S.D.; Kleer, C.G. The Polycomb Group Protein EZH2 Impairs DNA Repair in Breast Epithelial Cells. Neoplasia 2005, 7, 1011–1019.

- Gonzalez, M.E.; DuPrie, M.L.; Krueger, H.; Merajver, S.D.; Ventura, A.C.; Toy, K.A.; Kleer, C.G. Histone Methyltransferase EZH2 Induces Akt-Dependent Genomic Instability and BRCA1 Inhibition in Breast Cancer. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 2360–2370.

- Hong, Z.; Jiang, J.; Lan, L.; Nakajima, S.; Kanno, S.-I.; Koseki, H.; Yasui, A. A polycomb group protein, PHF1, is involved in the response to DNA double-strand breaks in human cell. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, 2939–2947.

- Campbell, S.; Ismail, I.H.; Young, L.C.; Poirier, G.G.; Hendzel, M.J. Polycomb repressive complex 2 contributes to DNA double-strand break repair. Cell Cycle 2013, 12, 2675–2683.

- Karakashev, S.; Fukumoto, T.; Zhao, B.; Lin, J.; Wu, S.; Fatkhutdinov, N.; Park, P.-H.; Semenova, G.; Jean, S.; Cadungog, M.G.; et al. EZH2 Inhibition Sensitizes CARM1-High, Homologous Recombination Proficient Ovarian Cancers to PARP Inhibition. Cancer Cell 2020, 37, 157–167.e6.

- Dhalluin, C.; Carlson, J.E.; Zeng, L.; He, C.; Aggarwal, A.K.; Zhou, M.-M. Structure and ligand of a histone acetyltransferase bromodomain. Nature 1999, 399, 491–496.

- Wu, S.-Y.; Chiang, C.-M. The Double Bromodomain-containing Chromatin Adaptor Brd4 and Transcriptional Regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 13141–13145.

- Shi, J.; Vakoc, C.R. The Mechanisms behind the Therapeutic Activity of BET Bromodomain Inhibition. Mol. Cell 2014, 54, 728–736.

- Lovén, J.; Hoke, H.A.; Lin, C.Y.; Lau, A.; Orlando, D.A.; Vakoc, C.R.; Bradner, J.E.; Lee, T.I.; Young, R.A. Selective Inhibition of Tumor Oncogenes by Disruption of Super-Enhancers. Cell 2013, 153, 320–334.

- Hnisz, D.; Schuijers, J.; Lin, C.Y.; Weintraub, A.S.; Abraham, B.; Lee, T.I.; Bradner, J.E.; Young, R.A. Convergence of Developmental and Oncogenic Signaling Pathways at Transcriptional Super-Enhancers. Mol. Cell 2015, 58, 362–370.

- Yang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Shan, W.; Hu, Z.; Yuan, J.; Pi, J.; Wang, Y.; Fan, L.; Tang, Z.; Li, C.; et al. Repression of BET activity sensitizes homologous recombination–proficient cancers to PARP inhibition. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9, eaal1645.

- Mio, C.; Gerratana, L.; Bolis, M.; Caponnetto, F.; Zanello, A.; Barbina, M.; Di Loreto, C.; Garattini, E.; Damante, G.; Puglisi, F. BET proteins regulate homologous recombination-mediated DNA repair: BRCAness and implications for cancer therapy. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 144, 755–766.

- Peng, G.; Lin, C.C.-J.; Mo, W.; Dai, H.; Park, Y.-Y.; Kim, S.M.; Peng, Y.; Mo, Q.; Siwko, S.; Hu, R.; et al. Genome-wide transcriptome profiling of homologous recombination DNA repair. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 1–11.

- Sun, C.; Yin, J.; Fang, Y.; Chen, J.; Jeong, K.J.; Chen, X.; Vellano, C.P.; Ju, Z.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, D.; et al. BRD4 Inhibition Is Synthetic Lethal with PARP Inhibitors through the Induction of Homologous Recombination Deficiency. Cancer Cell 2018, 33, 401–416.e8.

More