Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Rita Xu and Version 3 by Rita Xu.

The tourism industry has evolved as a major contributor to economic development and employment creation globally. Over the past seven decades, the tourism industry has experienced growth in both developed and developing countries. Although tourism has significant economic benefits, it often compromises environmental quality. Thus, tourism sustainability becomes an important element in managing the industry. Tourism sustainability has emerged as a leading policy paradigm and is important because tourism is a significant contributor to carbon emissions worldwide.

- resident perceptions

- tourism sustainability

1. Sustainable Tourism

Sustainable tourism has gained widespread acceptance to reconcile and balance various aspects of heritage tourism, tourism management, social pressures, and economic development [1]. Noting the link between tourism development and environmental quality [2][3], Adriana [4] found that public pressures can promote green supply chains, but organizational factors and strategic myopia hinders the implementation of sustainable tourism. Chan et al. [5] found that environmental knowledge, environmental awareness, and environmental concern are positively associated with tourists’ ecological behaviour in a survey of 438 hotel employees in Hong Kong. Chen and Tung [6], Dunk et al. [7], and Suriñach and Wöber [8] indicated that the tourism industry uses many disposable products, which may lead to soil and water pollution.

In a study by Movono et al. [9], respondents of a Fijian village revealed that the first 20 years of tourism brought much social and economic change in the community that was both good and bad. The women of Votualailai village in Fiji were the first to receive full-time employment when the Naviti resort opened. More people left farming and fishing to focus on paid work which changed livelihood activities [10]. Movono et al. [11] also found that tourism involvement has driven a wedge between traditional human-ecology relationships. Villages now recognise these changes and find ways to rescue what all has been lost and adapt to challenges. The effects on stakeholders need to be considered in sustainable tourism planning [12].

2. Sustainability in SIDS

SIDS perceive tourism as an invaluable tool that helps them realize their national and development aspirations [13][14][15][16]. Perceptions of the various social impacts of tourism have been extensively studied since the 1970s [17]. Tosun [17] stated that studies have focused on how segments of the host communities react to tourism impacts. However, further investigations in other geographical locations are required to help develop theories on the perceptions of the social impacts of tourism [17]. Various models of perceptions of the impacts of tourism have been developed [18][19][20].

SIDS depend on tourism for exports and contribution to GDP [21]. SIDS depend on imports of food, water, and raw materials [22]. This dependence can cause island destinations to focus on economic gains and ignore social and environmental issues that tourism can potentially have [23][24][25][26]. Negative issues facing SIDS include habitat destruction, natural resource depletion, erosion, inflation, increasing crime, and loss of local identity [22][23][27]. In addition to these, the growing population of SIDS put pressure on limited resources, and sustainable alternatives are difficult to implement due to cost, location, lack of technical expertise, and infrastructure issues. Due to these reasons and limited size, marginalization, and resource limitations, SIDS will face significant challenges in the sustainable development of tourism [28].

Indigenous communities have taken advantage of the socio-economic and environmental potential. They have created new businesses, created natural protected areas, gained formal employment, and adapted to tourism as a means of creating a living [9][29]. Studies on the perceptions of sustainability in tourism are essential to small island economies because they rely extensively on tourism for growth and development [30] and are vulnerable to environmental degradation, exploitation, and rising sea levels. Mainstream tourism has been found to entail unsustainable practices relating to environmental and societal impacts [1].

3. Residents Perceptions towards Tourism Impacts

Nunkoo and Ramkissoon [31] used a sample of 230 residents to examine the resident attitudes towards tourism in Port Louis, Mauritius. The authors found that while residents recognize the positive impact of tourism, they are also concerned with some negative influences of the industry. Rughoobur-Seetah [32] also conducted a similar study in Mauritius with a sample of 178 residents. The results of this study indicated that residents agree that tourism has economic value to the island while they also believe that the environment should not be harmed, and more community participation should be initiated. Ribeiro et al. [33] studied a sample of 418 residents from Cape Verde. They found that economic factors had a direct influence on the pro-tourism development behaviour. The study also found that both attitudes to positive impacts and negative impacts have a direct influence on residents’ pro-tourism development behaviour. The authors also recommended that it is important for policymakers to guarantee that tourism developments will have more benefits than costs. In SIDS, residents’ perspectives are not considered and frequently excluded from decision making related to tourism. Therefore, there is a need to include residents in the process of development as it allows for greater transparency, equity, and sustainability of tourism resources [27].

Rahman and Reynolds [34] established a comprehensive model of consumers’ behavior decisions and examined the interaction among consumers’ biospheric value, willingness to sacrifice for the environment, and behavioural intentions. They conclude that the biospheric value influences consumers’ willingness to sacrifice for the environment. Torres-Delgado and Saarinen [35] and Blancas et al. [36] introduced composite indicators to measure and quantify socio-economic dimensions of sustainable tourism for decision making. Sustainable tourism can defend environmental protection, improve community’s health and education, and reduce poverty in destinations [21][37].

4. Sustainable Tourism Planning Model

Padin [38][39] proposed a sustainable tourism planning model based on the triple bottom line (TBL) dimensions, viz., ecological, social, and economic planning. “Triangle Nijkamp” initiated the model of this study which arises in Hall [40]. Padin’s TBL approach has been applied by numerous scholars such as Svensson and Wagner [41][42], Hunter [43], Høgevold [44], Cambra-Fierro and Ruiz-Benı’tez [45], Dos Santos [46], Høgevold and Svensson [47], Pilgram [48], Padin et al. [39], Ferro et al. [49], and Grah et al. [50]. The TBL approach asserts that stakeholders show concern towards tourism activities’ economic, ecological, and social aspects. These conflicting relationships are referred to as the TBL approach [51].

The literature treats the three dimensions as independent and uncoordinated. Thus, it is crucial to ascertain relationships between these dimensions. The stakeholders or the so-called social capital are of utmost importance to the model since it represents the same population for whom and why this process exists. Many authors have stated the importance of participation of the stakeholders in any sustainable process or planning in tourism [52][53][54][55][56][57][58][59][60]. However, this is problematic in practice [61]. Studies that have tested the TBL elements separately include those by van Beurden and Gössling [62], Dixon-Fowler et al. [63], Albertini [64], Javed et al. [65], Esteban-Sanchez et al. [66], Liao et al. [67], Wang and Sarkis [68], and Theodoulidis et al. [69].

References to sustainability in TBL is based on theory [41][42][43][48] and in case studies [41][42][44][45][46][47]. These works raise three dimensions, socio-cultural, economic, and environmental, and finding the right balance between them ensures long-term sustainability [38]. Sustainable tourism is a balance between tourism development and the sustainability of the environment. Public pressures ensure that sustainability happens while organizational factors hinder it. For sustainable tourism to occur, all stakeholders of the tourism industry must work together. The TBL model suggests that there needs to be a balance between economic, social, and environmental factors for sustainability to occur. Researchers have also studied the TBL elements separately. It is vital to understand whether the relevant populace is aware of the negative impacts of tourism. An absence of awareness of the negative issues will not lead to any public pressure to resolve the issues.

5. Tourism and Fiji

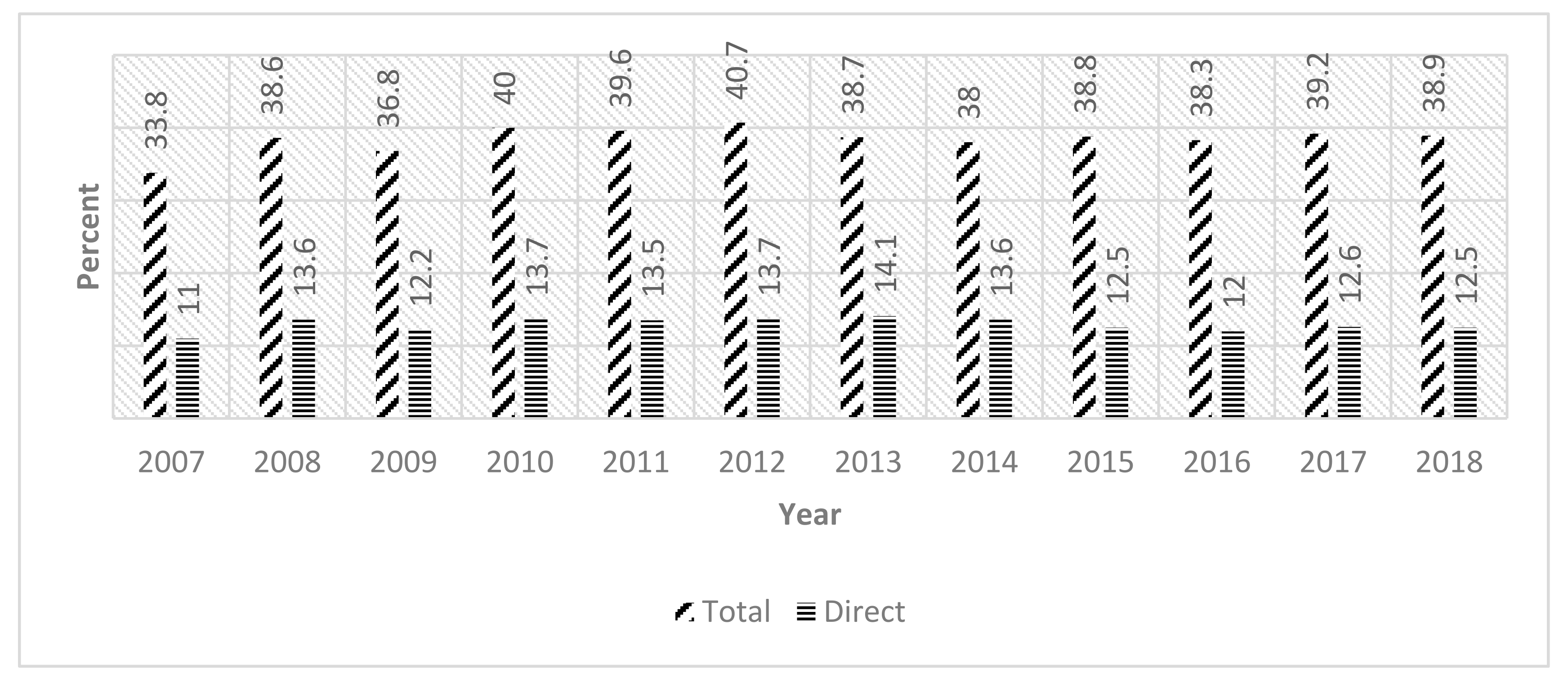

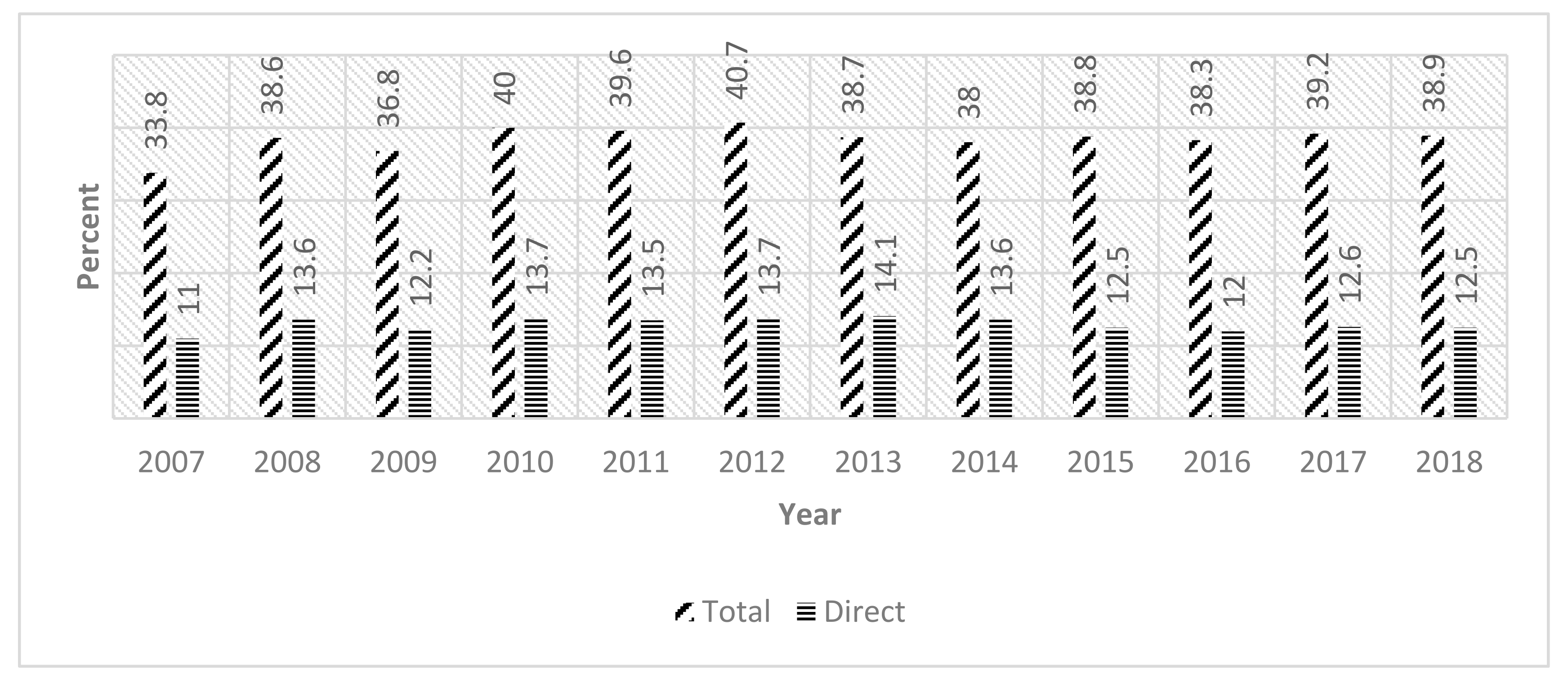

Tourism contributes about 34 percent towards GDP and 26.3 percent of total employment to Fiji and is an essential driver of economic activity [70] (Figure 1), which is higher than the average of 33 percent in other pacific island countries. There is a growing demand from tourists for multiple pit-stop vacations [71]. Fiji can benefit from island hopping by developing holiday packages for multiple destinations for long haul tourists through its cruise ship, airline, and rental networks [72]. Flying to smaller island destinations provides tourists with a great aerial view of Fiji and showcases unique features such as reefs and atolls. Resorts and excursion sites link through land and air transport [72].

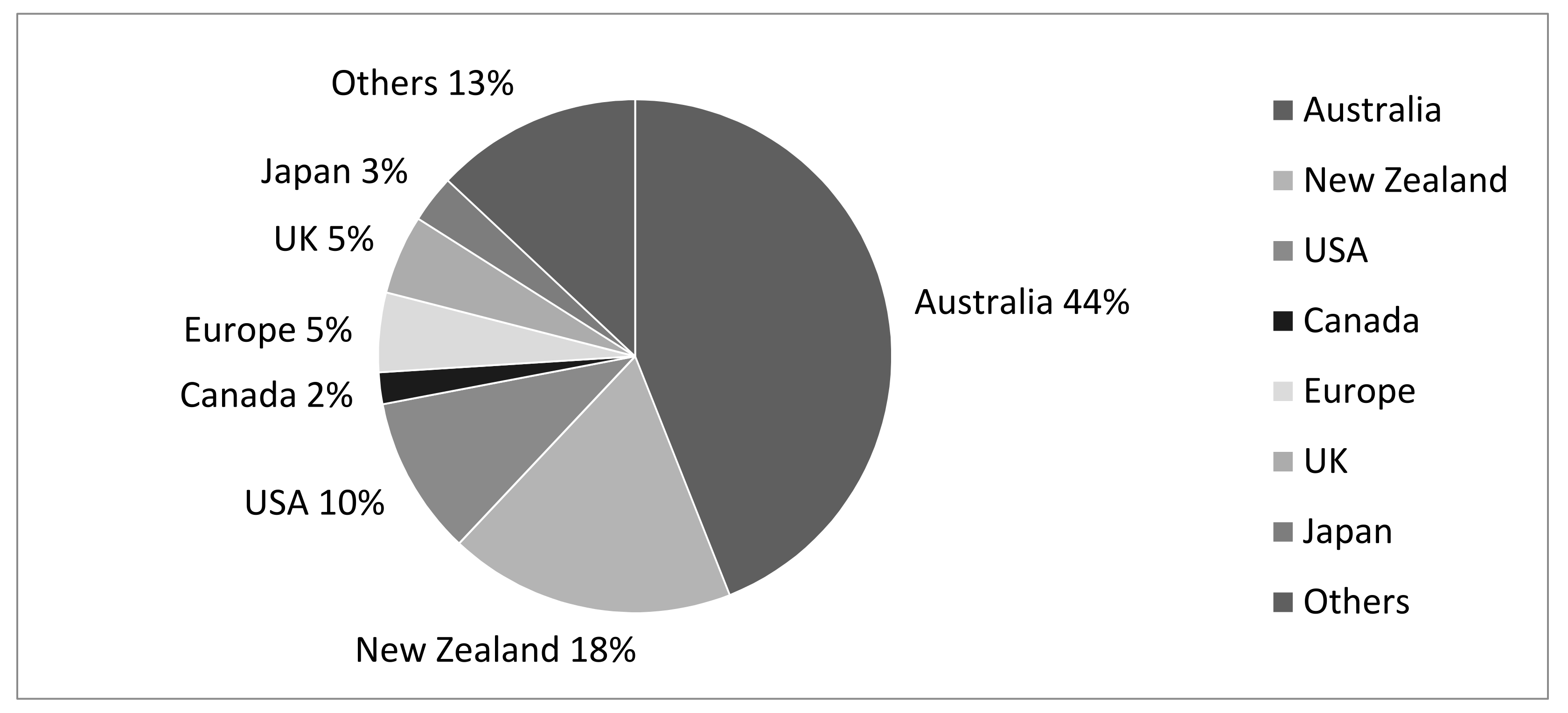

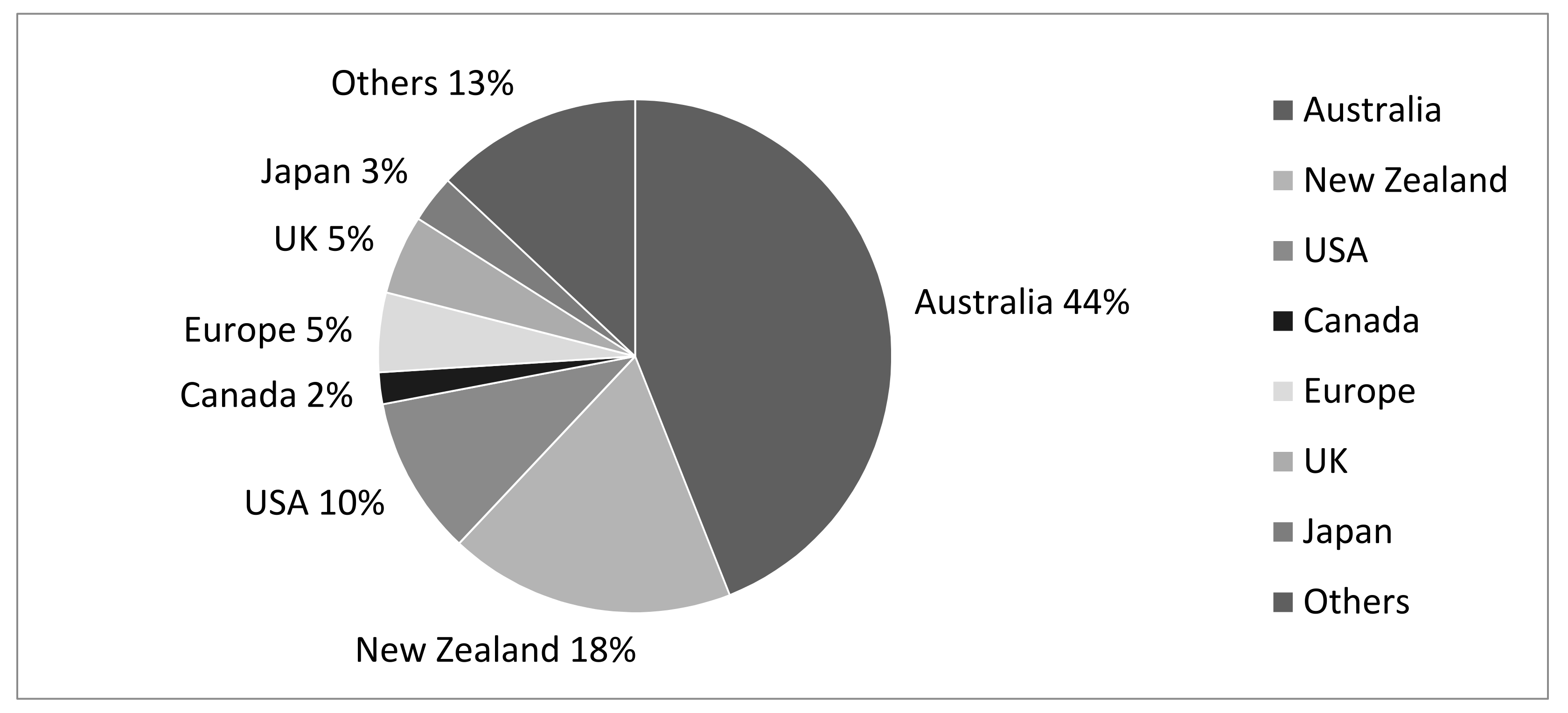

Fiji has the largest tourism industry in the South Pacific, employing about 26.3 percent of the total workforce [70]. COVID-19 had a massive impact on the tourism industry as the economy was expected to contract by 21.7 percent due to insufficient tourism activity and its effects on the economy. The impact also increased unemployment and further pushed households below the poverty line [73]. This is explained by the fact that 27 percent of staff from tourism businesses are on reduced hours and days, 25 percent are on leave without pay, and 8 percent have been made redundant. Additionally, 50 percent of tourism businesses are hibernating or closed with anticipation that if the COVID-19 situation did not change by November of 2020, around 500 tourism and non-tourism businesses anticipate bankruptcy [74]. The primary sources of tourists to Fiji are from Australia, New Zealand, and the United States, each contributing about 44 percent, 18 percent, 10 percent of arrivals, respectively (Figure 2).

Fiji has the largest tourism industry in the South Pacific, employing about 26.3 percent of the total workforce [70]. COVID-19 had a massive impact on the tourism industry as the economy was expected to contract by 21.7 percent due to insufficient tourism activity and its effects on the economy. The impact also increased unemployment and further pushed households below the poverty line [73]. This is explained by the fact that 27 percent of staff from tourism businesses are on reduced hours and days, 25 percent are on leave without pay, and 8 percent have been made redundant. Additionally, 50 percent of tourism businesses are hibernating or closed with anticipation that if the COVID-19 situation did not change by November of 2020, around 500 tourism and non-tourism businesses anticipate bankruptcy [74]. The primary sources of tourists to Fiji are from Australia, New Zealand, and the United States, each contributing about 44 percent, 18 percent, 10 percent of arrivals, respectively (Figure 2).

Tourism Fiji is the marketing arm of the Fijian government that promotes Fiji as a tourism destination throughout the world. Tourism Fiji has international offices in Sydney, Auckland, Los Angeles, London, Germany, and China, with representatives in India, Singapore, and Japan. Fiji has a good network of transport services, including buses, ferries, and taxis, and has two domestic airlines, Fiji Link and Northern Air, which operate between the outer islands. Yachts, cruises, and car rentals are also great ways of exploring Fiji [75]. Growing tourist numbers indicate Fiji’s popularity as a tourism destination. From the year 2000, tourist arrivals have grown by about 187 percent to reach about 900,000 in 2018. Tourism earnings were FJ $2.08 billion in 2018, which brings Fiji close to achieving its 2021 targets [76].

Major tourism infrastructures in Fiji, such as hotels, are typically in the form of greenfield investments. This results in significant long-term leakages and repatriation of profits [77][78], which further complicates attempts to develop linkages between tourism facilities and local economies [77][79][80][81][82]. This leads to unequal spatial and geographic development [81]. Narayan and Prasad [80] stated that 94% of the 132 tourism projects implemented between 1988 and 2000 were foreign-owned, with just 6% local ownership. Farrelly [83] argued that there may be a need to reform Fiji’s local traditional decision-making systems for local ownership ventures in the future.

Lastly, tourism is affected by political instability and pandemics [84]. Fiji has gone through four coups since 1987 and numerous changes in government [29]. At present, Fiji’s tourism sector is at a halt due to the coronavirus pandemic. Border closures meant job losses to 40 percent of the Fijian workforce and a ripple effect on businesses indirectly related to the tourism industry. The Reserve Bank of Fiji Economic Review of April 2020 indicated that the economy was expected to contract more sharply than the initial −4.3% estimated for 2020 due to a significant decrease in tourism activity and the ripple effect on the rest of the economy. The report also stated that 65,800 members had withdrawn from the Fiji National Provident Fund from a scheme targeted to individuals affected by the COVID-19 pandemic [85].

Tourism Fiji is the marketing arm of the Fijian government that promotes Fiji as a tourism destination throughout the world. Tourism Fiji has international offices in Sydney, Auckland, Los Angeles, London, Germany, and China, with representatives in India, Singapore, and Japan. Fiji has a good network of transport services, including buses, ferries, and taxis, and has two domestic airlines, Fiji Link and Northern Air, which operate between the outer islands. Yachts, cruises, and car rentals are also great ways of exploring Fiji [75]. Growing tourist numbers indicate Fiji’s popularity as a tourism destination. From the year 2000, tourist arrivals have grown by about 187 percent to reach about 900,000 in 2018. Tourism earnings were FJ $2.08 billion in 2018, which brings Fiji close to achieving its 2021 targets [76].

Major tourism infrastructures in Fiji, such as hotels, are typically in the form of greenfield investments. This results in significant long-term leakages and repatriation of profits [77][78], which further complicates attempts to develop linkages between tourism facilities and local economies [77][79][80][81][82]. This leads to unequal spatial and geographic development [81]. Narayan and Prasad [80] stated that 94% of the 132 tourism projects implemented between 1988 and 2000 were foreign-owned, with just 6% local ownership. Farrelly [83] argued that there may be a need to reform Fiji’s local traditional decision-making systems for local ownership ventures in the future.

Lastly, tourism is affected by political instability and pandemics [84]. Fiji has gone through four coups since 1987 and numerous changes in government [29]. At present, Fiji’s tourism sector is at a halt due to the coronavirus pandemic. Border closures meant job losses to 40 percent of the Fijian workforce and a ripple effect on businesses indirectly related to the tourism industry. The Reserve Bank of Fiji Economic Review of April 2020 indicated that the economy was expected to contract more sharply than the initial −4.3% estimated for 2020 due to a significant decrease in tourism activity and the ripple effect on the rest of the economy. The report also stated that 65,800 members had withdrawn from the Fiji National Provident Fund from a scheme targeted to individuals affected by the COVID-19 pandemic [85].

Figure 1. Tourism’s direct and total contribution to Fiji’s GDP (2007–2018). Source: World Tourism and Travel Council, Country Reports (various issues).

Figure 2. Key source markets for international tourism in Fiji (1975–2018). Source: Fiji Bureau of Statistics and Reserve Bank of Fiji Quarterly Reviews (various issues).

References

- Buckley, R. Sustainable tourism: Research and reality. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 528–546.

- De Vita, G.; Katircioglu, S.; Altinay, L.; Fethi, S.; Mercan, M. Revisiting the environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis in a tourism development context. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 16652–16663.

- Katircioglu, S.T.; Feridun, M.; Kilinc, C. Estimating tourism-induced energy consumption and CO2 emissions: The case of Cyprus. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 29, 634–640.

- Adriana, B. Environmental supply chain management in tourism: The case of large tour operators. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 1385–1392.

- Chan, E.S.; Hon, A.H.; Chan, W.; Okumus, F. What drives employees’ intentions to implement green practices in hotels? The role of knowledge, awareness, concern and ecological behaviour. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 40, 20–28.

- Chen, M.F.; Tung, P.J. Developing an extended theory of planned behavior model to predict consumers’ intention to visit green hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 36, 221–230.

- Dunk, R.M.; Gillespie, S.A.; MacLeod, D. Participation and retention in a green tourism certification scheme. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 1585–1603.

- Suriñach, J.; Wöber, K. Introduction to the special focus: Cultural tourism and sustainable urban development. Tour. Econ. 2017, 23, 239–242.

- Movono, A.; Pratt, S.; Harrison, D. Adapting and reacting to tourism development: A tale of two villages on Fiji’s Coral Coast. In Tourism in Pacific Islands; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2015; pp. 125–141.

- Movono, A.; Dahles, H. Female empowerment and tourism: A focus on businesses in a Fijian village. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2017, 22, 681–692.

- Movono, A.; Dahles, H.; Becken, S. Fijian culture and the environment: A focus on the ecological and social interconnectedness of tourism development. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 26, 451–469.

- Xu, F.; Fox, D. Modelling attitudes to nature, tourism and sustainable development in national parks: A survey of visitors in China and the, U.K. Tour. Manag. 2014, 45, 142–158.

- Briedenhann, J.; Wickens, E. Tourism routes as a tool for the economic development of rural areas—vibrant hope or impossible dream? Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 71–79.

- Lee, C.C.; Chang, C.P. Tourism development and economic growth: A closer look at panels. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 180–192.

- Durbarry, R. Tourism and economic growth: The case of Mauritius. Tour. Econ. 2004, 10, 389–401.

- Movono, A. Tourism’s Impact on Communal Development in Fiji: A Case Study of the Socio-Economic Impacts of The Warwick Resort and Spa and The Naviti Resort on the Indigenous Fijian Villages of Votua and Vatuolalai. Master’s Thesis, University of the South Pacific, Suva, Fiji, March 2012.

- Tosun, C. Challenges of sustainable tourism development in the developing world: The case of Turkey. Tour. Manag. 2001, 22, 289–303.

- Doxey, G.V. A causation theory of visitor-resident irritants: Methodology and research inferences. In Proceedings of the Sixth Annual Conference of the Travel and Tourism Research Associations, San Diego, CA, USA, 8–11 September 1975; pp. 195–198.

- Smith, V. Eskimo tourism: Micro-models and marginal men. In Host and Guests: The Anthropology of Tourism; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1989.

- Butler, R.W. The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution: Implications for management of resources. Tour. Area Life Cycle 2006, 1, 3–12.

- Unwto.org. 2015. Available online: http://sdt.unwto.org/content/about-us-5 (accessed on 3 July 2015).

- Dodds, R.; Graci, S. Sustainable Tourism in Island Destinations; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2012.

- Lück, M. The Encyclopedia of Tourism and Recreation in Marine Environments; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2008.

- Roberts, S.; Lewis-Cameron, A. Small Island Developing States: Issues and Prospects. In Marketing Island Destinations; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010.

- Boukas, N.; Ziakas, V. A chaos theory perspective of destination crisis and sustainable tourism development in islands: The case of Cyprus. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2014, 11, 191–209.

- Niles, D.; Baldacchino, G. Introduction: On island futures. In Island Futures; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2011; pp. 1–7.

- Dredge, D.; Jamal, T. Progress in tourism planning and policy: A post-structural perspective on knowledge production. Tour. Manag. 2015, 51, 285–297.

- Graci, S.; Van Vliet, L. Examining stakeholder perceptions towards sustainable tourism in an island destination. The Case of Savusavu, Fiji. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2020, 17, 62–81.

- Scheyvens, R.; Russell, M. Tourism and poverty alleviation in Fiji: Comparing the impacts of small-and large-scale tourism enterprises. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 417–436.

- Brau, R.; Lanza, A.; Pigliaru, F. How Fast Are the Tourism Countries Growing? The Cross-Country Evidence; Centre for North South Economic Research, University of Cagliari: Cagliari, Italy, 2003.

- Nunkoo, R.; Ramkissoon, H. Small island urban tourism: A residents’ perspective. Curr. Issues Tour. 2010, 13, 37–60.

- Rughoobur-Seetah, S. Residents’ perception on factors impeding sustainable tourism in sids. Prestig. Int. J. Manag. IT-Sanchayan 2019, 8, 61–86.

- Alector-Ribeiro, M.; Pinto, P.; Albino-Silva, J.; Woosman, K.M. Resident’s attitudes and the adoption of pro-tourism behaviour: The case of developing islands countries. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 523–537.

- Rahman, I.; Reynolds, D. Predicting green hotel behavioral intentions using a theory of environmental commitment and sacrifice for the environment. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 52, 107–116.

- Torres-Delgado, A.; Saarinen, J. Using indicators to assess sustainable tourism development: A review. Tour. Geogr. 2014, 16, 31–47.

- Blancas, F.J.; Lozano-Oyola, M.; González, M.; Caballero, R. Sustainable tourism composite indicators: A dynamic evaluation to manage changes in sustainability. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016, 24, 1403–1424.

- Catibog-Sinha, C. Biodiversity conservation and sustainable tourism: Philippine initiatives. J. Herit. Tour. 2010, 5, 297–309.

- Padin, C. A sustainable tourism planning model: Components and relationships. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2012, 24, 510–518.

- Padin, C.; Ferro, C.; Wagner, B.; Valera, J.C.; Høgevold, N.M.; Svensson, G. Validating a triple bottom line construct and reasons for implementing sustainable business practices in companies and their business networks. Corp. Gov. 2016, 15, 849–865.

- Hall, C.M. Tourism Planning: Policies, Processes and Relationships; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2008.

- Svensson, G.; Wagner, B. A process directed towards sustainable business operations and a model for improving the GWP-footprint (CO2e) on Earth. Manag. Environ. Qual. 2011, 22, 451–462.

- Svensson, G.; Wagner, B. Transformative Business Sustainability: Multi-Layer Model and Network of e-Footprint Sources. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2011, 23, 334–352.

- Hunter, C. Sustainable tourism as an adaptive paradigm. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 850–867.

- Høgevold, N.M. A Corporate Effort towards a Sustainable Business Model: A Case Study from the Norwegian Furniture Industry. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2011, 23, 392–400.

- Cambra-Fierro, J.; Ruiz-Benítez, R. Sustainable Business Practices in Spain: A Two-Case Study. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2011, 23, 401–412.

- Dos Santos, M.A. Minimizing the Business Impact on the Natural Environment: A Case Study of Woolworths South Africa. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2011, 23, 384–391.

- Høgevold, N.M.; Svensson, G. A business sustainability model: A European case study. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2012, 27, 142–151.

- Pigram, J.J. Sustainable tourism-policy considerations. J. Tour. Stud. 1990, 1, 2–9.

- Ferro, C.; Padin, C.; Høgevold, N.; Svensson, G.; Varela, J.C. Validating and expanding a framework of a triple bottom line dominant logic for business sustainability through time and across contexts. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2019, 34, 95–116.

- Grah, B.; Dimovski, V.; Peterlin, J. Managing sustainable urban tourism development: The case of Ljubljana. Sustainability 2020, 12, 792.

- De Lange, D.E. Start-up sustainability: An insurmountable cost or a life-giving investment? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 156, 838–854.

- Liu, Z. Sustainable tourism development: A critique. J. Sustain. Tour. 2003, 11, 459–475.

- Bramwell, B.; Sharman, A. Collaboration in local tourism policymaking. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 392–415.

- Murphy, P.E. Tourism: A Community Approach; National Parks Today: New York, NY, USA, 1991; Green Guide for Tourism: Methuen, MA, USA, 1985; Volume 31, pp. 224–238.

- Hall, D.R.; Richards, G. Tourism and Sustainable Community Development; Routledge: London, UK, 2000.

- Scheyvens, R. Local involvement in managing tourism. In Tourism in Destination Communities; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2003; pp. 229–252.

- Simmons, D.G. Community participation in tourism planning. Tour. Manag. 1994, 15, 98–108.

- Telfer, D.J. Development issues in destination communities. In Tourism in Destination Communities; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2003; pp. 155–180.

- Tosun, C. Limits to community participation in the tourism development process in developing countries. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 613–633.

- Tosun, C. Expected nature of community participation in tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 493–504.

- Hansen, H.S.; Mäenpää, M. An overview of the challenges for public participation in river basin management and planning. Manag. Environ. Qual. 2008, 19, 67–84.

- Van Beurden, P.; Gössling, T. The worth of values–a literature review on the relation between corporate social and financial performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 82, 407–424.

- Dixon-Fowler, H.R.; Slater, D.J.; Johnson, J.L.; Ellstrand, A.E.; Romi, A.M. Beyond “does it pay to be green?” A meta-analysis of moderators of the CEP–CFP relationship. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 112, 353–366.

- Albertini, E. Does environmental management improve financial performance? A meta-analytical review. Organ. Environ. 2013, 26, 431–457.

- Javed, M.; Rashid, M.A.; Hussain, G. When does it pay to be good–A contingency perspective on corporate social and financial performance: Would it work? J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 133, 1062–1073.

- Esteban-Sanchez, P.; de la Cuesta-Gonzalez, M.; Paredes-Gazquez, J.D. Corporate social performance and its relation with corporate financial performance: International evidence in the banking industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 1102–1110.

- Liao, P.C.; Shih, Y.N.; Wu, C.L.; Zhang, X.L.; Wang, Y. Does corporate social performance pay back quickly? A longitudinal content analysis on international contractors. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 170, 1328–1337.

- Wang, Z.; Sarkis, J. Corporate social responsibility governance, outcomes, and financial performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 1607–1616.

- Theodoulidis, B.; Diaz, D.; Crotto, F.; Rancati, E. Exploring corporate social responsibility and financial performance through stakeholder theory in the tourism industries. Tour. Manag. 2017, 62, 173–188.

- World Travel & Tourism Council. Fiji: 2020 Annual Research Key Highlights. 2020. Available online: https://wttc.org/Research/Economic-Impact/moduleId/704/itemId/110/controller/DownloadRequest/action/QuickDownload (accessed on 9 March 2021).

- Ayala, H. The Unresearched Phenomenon of “Hotel Circuits”. Hosp. Res. J. 1993, 16, 59–73.

- About Tourism Fiji 2019. Available online: https://www.fiji.travel/us/about-tourism-fiji (accessed on 8 September 2019).

- United Nations Pacific. Socio-Economic Impact Assessment of COVID-19 in Fiji. 2020. Available online: https://www.undp.org/content/dam/fiji/docs/SEIA%20Fiji%20Consolidated%20Report.pdf (accessed on 23 March 2021).

- International Finance Corporation. IFC Fiji COVID-19 Business Survey: Tourism Focus. Available online: https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/4fc358f9-5b07-4580-a28c-8d24bfaf9c63/Fiji+COVID-19+Business+Survey+Results+-+Tourism+Focus+Final.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CVID=ndnpJrE (accessed on 23 March 2021).

- Tourism Fiji. Available online: https://www.fiji.travel/us/information/transport (accessed on 8 September 2019).

- Fiji’s Earnings from Tourism. Available online: https://www.statsfiji.gov.fj/index.php/latest-releases/tourism-and-migration/earnings-from-tourism/925-fiji-s-earnings-from-tourism-december-quarter-and-annual-2018 (accessed on 4 February 2020).

- Berno, T. Bridging Sustainable Agriculture and Sustainable Tourism to Enhance Sustainability; Sustainable Development Policy and Administration; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2017; pp. 207–221.

- Prasad, B.C.; Narayan, P.K. Reviving growth in the Fiji islands: Are we swimming or sinking. Pac. Econ. Bull. 2008, 23, 5–26.

- Mahadevan, R. The rough global tide and political storm in Fiji call for swimming hard and fast but with a different stroke. Pac. Econ. Bull. 2009, 24, 1–23.

- Narayan, P.K.; Prasad, B.C. Fiji’s sugar, tourism and garment industries: A survey of performance, problems and potentials. Fijian Stud. 2003, 1, 3–27.

- Rao, M. Challenges and Issues in Pro-Poor Tourism in South Pacific Island Countries: The Case of Fiji Islands; School of Economics, University of the South Pacific: Suva, Fiji, 2006.

- Veit, R. Tourism, Food Imports and the Potential of Import-Substitution Policies in Fiji; Fiji AgTrade, Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forests: Suva, Fiji, 2007.

- Farrelly, T.A. Indigenous and democratic decision-making: Issues from community-based ecotourism in the Boumā National Heritage Park, Fiji. J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 817–835.

- Smeral, E. Tourism forecasting performance considering the instability of demand elasticities. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 913–926.

- Economic Review April 2020. Available online: https://www.rbf.gov.fj/getattachment/Publications/Economic-Review-April-2020/Economic-Review-April-2020-(11).pdf?lang=en-US (accessed on 3 May 2020).

More