Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Rita Xu and Version 1 by JOANNA ROSAK-SZYROCKA.

Environmental protection, sustainable development, quality, and value have become the goals of societal development in the twenty-first century. As the core of environmental protection, the new energy sector has become a widespread trend.

- quality

- value

- vuca

- CIT method

- Pareto-Lorenz diagram

- quality management model

- consumer

1. Introduction

Climate change has long been one of the most difficult environmental challenges to address in recent years. Due to high volumes of greenhouse gas emissions, climate change problems, such as global warming, have posed a challenge for human populations to achieve sustainable development [1,2][1][2]. In the corporate world, the customer is seen as the king [3]. The tagline “Right or wrong, the customer is always right” was coined by Marshall, a well-known and pioneering retailer. This phrase denotes a high level of client satisfaction [4,5,6][4][5][6]. COVID-19, which is now in progress, has had an impact on international trade and the global energy market [7]. A holistic approach to people and their needs is required in today’s socio-economic reality, particularly in one of the European Union countries where dynamic processes are happening and are driven primarily by expanding globalization and advancing climate change [8]. According to Micheletti [9,10,11][9][10][11], views are changing and people are becoming more sensitive to social and environmental issues, and these developments are reflected in ethical consumption. This is the result of rising consumer awareness, as well as decisions based on values, virtue, and ethics. Entrepreneurs recognize that because their products and features are so comparable to those of their customers, they must seek a competitive advantage by enhancing quality in other areas of their business. An organization’s competitiveness assures its long-term success in the commercial sector. The competitive advantage of a company helps to make and pass on value to customers [12,13][12][13].

Today’s customers are exceedingly demanding and quality-conscious; they know exactly what they want from a product as well as from the energy market services. Quality is a dynamic condition related to product and customer satisfaction that enables customers to form long-term mutually beneficial connections with the organization via the application of a special force [14]. High quality is viewed as a key competitive advantage and a source of added value for both the company and its consumers [15,16][15][16]. There are three types of perspectives on the relationship between quality and value [17,18,19,20,21][17][18][19][20][21]:

-

The product’s use-value is the same as its quality.

-

Quality is defined as a product’s ability to satisfy a specific need, i.e., it is a carrier of utility value.

-

Quality is similar to management efficiency, which is measured by the ratio of use-value to the cost of making and using the thing you make and use.

The customer is the most important person in the company, even when they write or call; they are not dependent on the company, the company is dependent on them. The client cannot be won because they will leave the competition; they do not interfere with a companies work but are its meaning and purpose; they would like to solve their problems; the company’s task is to solve them for the benefit of both the client and the company [22,23][22][23]. There are studies that examine quality and value but from an awareness perspective [24,25[24][25][26][27][28],26,27,28], a trust perspective [29,30[29][30][31][32],31,32], or a sustainability perspective [33,34,35][33][34][35]. This case study aims at filling this research gap by examining what value and quality mean for the consumers of the energy market and what factors influence the quality and value of the energy market client. Household clients will become respondents (2404 respondents have taken part in the survey). A smart consumer (smartsumer) creates a new, as yet unknown category of consumer. A smartsumer does not have to be alone anymore to analyze source data about their consumption or to be aware of the impact of their activities on the environment. There is also no need for them to make any adjustments to their own self-production and own consumption for the needs of the system [24,25][24][25]. It is enough to be aware of the opportunities guaranteed by the broadly understood sector of public services. Actions: a smart consumer focuses on applications in which they manage specific ones with the best profile. Their activities are not the result of a passing trend; they are activities that were created by the surrounding reality and which became part of their everyday life routine, which they do not notice [26,27][26][27]. A high level of consumer awareness is not required for smart consumer awareness, which is analogous to the recipient’s knowledge in the earlier stages of evolution (e.g., prosumer). However, their “intelligence” is expressed in something else—the ability to connect tools using artificial intelligence with their own expectations and goals in the field of consumption. However, the creation of a smart sentence is a demanding evolutionary process that requires the occurrence of certain circumstances. These include, but are not limited to, a friendly investment climate, encouraging businesses to come up with new ideas, coherent information campaigns that teach people everything they need to know, and the development of IT systems that help people make decisions. In the context of external and internal variables influencing the organization, Table 1 shows the elements that are responsible for the rise in quality needs.

Table 1. The elements that are responsible for the rise in quality needs.

| Reason | Characteristic |

|---|---|

| Increase in customer expectations | Economic education |

| Change of service standards | |

| Subjective quality context | |

| Evolution of socio-cultural needs | |

| High degree of safety of use | |

| Increased reliability, ease of repair and maintenance | |

| Low price of products | |

| Full information about the product | |

| Trends in the economy | Increasing complexity |

| Improving operational efficiency | |

| Allowing free movement of capital and goods | |

| Reducing waste and overproduction | |

| Reducing the time it takes to introduce new ideas | |

| Legal regulations | Restrictions on safety |

| Environmental restrictions | |

| The civil liability for quality act guidelines/standards | |

| Corporate social responsibility assumptions | |

| The idea of long-term development | |

| Processes of inventions are becoming more global | |

| Key goals of the enterprise | Products of today |

| Excellent quality and dependability | |

| A high level of market acceptance of products | |

| Strong profit margins | |

| Risk mitigation | |

| The company’s good reputation | |

| A management strategy based on a system | |

| Costs that are not essential are eliminated | |

| Competition capital | A technological race |

| Increasing competition capital pressure | |

| Shifts in market structure | |

| Globalization of marketing processes | |

| Shorter product and service life cycles |

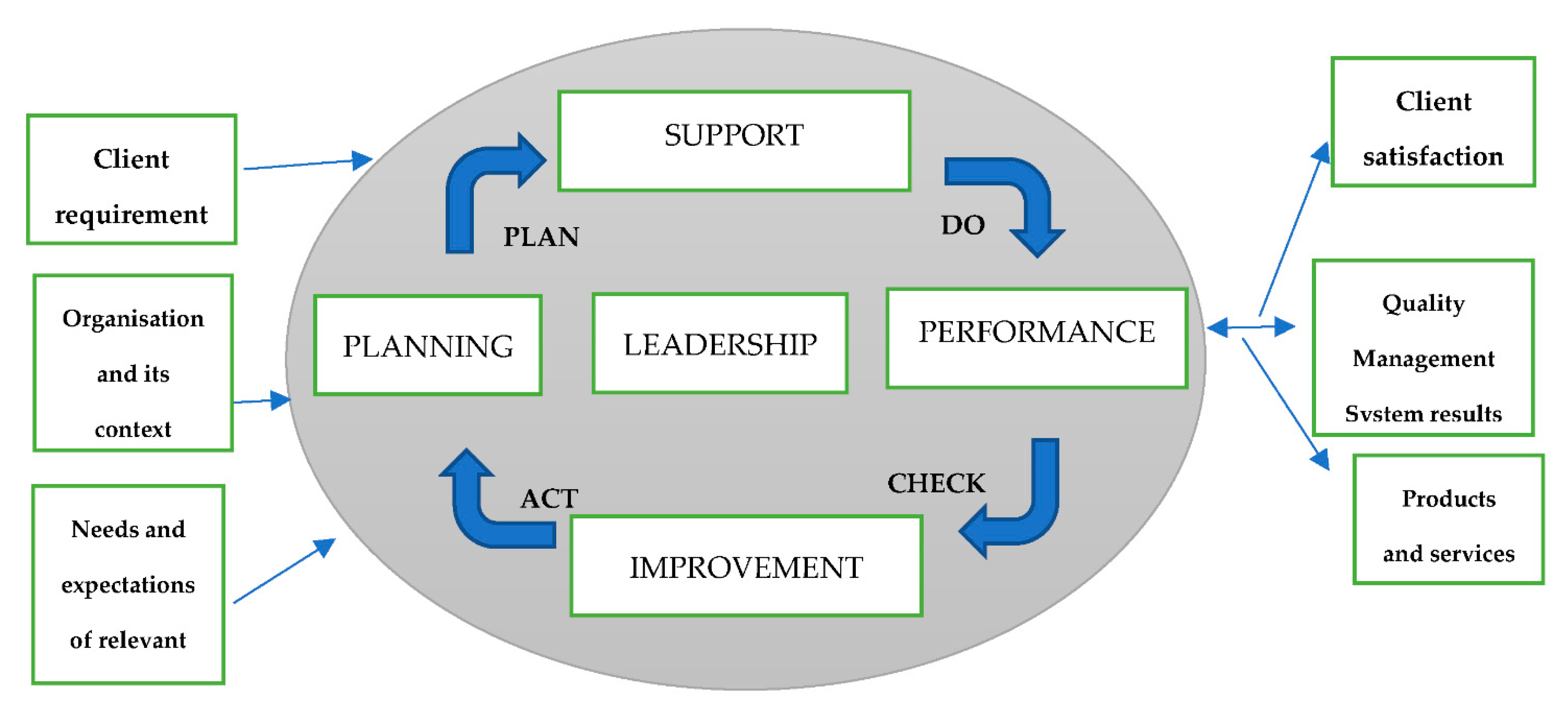

Currently, the ability to gain, for example, a client, is no longer the most important aspect of an enterprise’s activities; it is also the ability to keep that client by establishing a long-term relationship with them and providing them with the value he or she desires [28].

2. Quality of Energy Market Services

VUCA launched a brutal assault on the corporate and economic world in the twenty-first century. As a result, one of the most significant consequences is managers’ inability to define and comprehend their surroundings (not only in the power sector) [29]. Each organization must deal with its own unique and personalized VUCA environment, which is common in the power industry. Unfortunately, some organizations are unaware of its existence, and as a result, they fail to recognize signals from the outside world while continuing to follow established patterns. The VUCA strategy necessitates organizations to adjust their competency models and concentrate on their strengths [30]. Many new energy companies have successfully listed on the market in recent years, which was well-received by society. It is possible to assert that new energy stocks are a significant expression of social sustainability value [31[31][32],32], both in terms of technology and the quality of services provided. Poland’s energy industry is continually evolving. Changes and modifications in the direction of a competitive electricity market are based on the premise that competition among energy suppliers is the most effective way to cut energy prices and increase customer service quality. Furthermore, low-cost energy will allow us to compete with foreign businesses and raise our citizens’ living standards [33,34][33][34]. The ultimate recipients are categorized into two groups: the homes that are purchasing energy for community usage and the second group of recipients is entities other than homes that purchase energy from self-employed enterprises to meet their electricity demands [35,36][35][36]. Local energy trading businesses in Poland perform the functions of distribution network operators [37,38][37][38]. Currently, businesses that place a premium on quality should heed Drucker’s advice: “Yesterday’s great achievement must become today’s minimum”. While yesterday’s excellence must become today’s daily”. Excellent businesses care about their employees and believe in the power of what they can do [39,40][39][40]. They are concerned about the quality of their services. They adopt realistic improvements, and they understand that success necessitates the participation of all employees [41,42][41][42]. According to Taguchi, quality is what is missing, which means that everyone loses [43,44][43][44]. The current and widely recognized definition of quality focuses on client-centric concepts, with quality defined as meeting or, preferably, exceeding customer needs and expectations. To meet present and future societal needs, societal drives such as sustainability and digitization necessitate a quality perspective that includes a greater variety of stakeholders. The concept of quality over time was given several interpretations, for example, in the eyes of customers [45]. Conformance and the importance of eliminating variation in manufacturing processes were significant elements in defining quality in the early days of quality management. Shewhart [46] recognized the subjective aspect of quality, while Juran and Godfrey [47] emphasized this with a customer-focused definition of quality as “fitness for use”. Deming [48] extended this approach, specifically addressing the consumer when he stated that “quality should be oriented toward the needs of the customer, both present and future”. Deming and Juran pioneered a view of quality as a requirement of customers, which was later expanded to the concept of service quality [49,50][49][50]. Recent quality management research that incorporates sustainability perspectives emphasizes the necessity for a broader understanding of customer roles as well as other stakeholder viewpoints [51,52][51][52]. Suprapto et al. [53] discovered in earlier research that shop image has a favorable and significant impact on pricing consciousness, which in turn has an impact on repurchase intention. Furthermore, prior research by Beneke et al. [54] discovered that product quality and related price have a positive and significant impact on customers’ willingness to buy the goods, owing to the fact that the product purchased offers the value that consumers desire. According to previous research conducted by Bu et al. [55], product quality has a positive and significant impact on brand attitudes. Finally, according to Mostafa and Elseidi [56], price has a positive and significant effect on how people feel about a brand. Brand consciousness has a favorable and significant impact on brand sentiments. According to Yu et al. [57], brand image has a favorable and considerable impact on brand attitude [58]. Furthermore, Mowen and Minor [59] defined product quality as a comprehensive review process involving customers in order to improve a product’s or service’s performance. Product quality, according to Kato and Tsuda [60], can be judged in terms of performance, features, appropriateness, reliability, durability, serviceability, beauty, and consumer perception of quality. Consumer attitudes had a positive and significant impact on repurchase intention, according to Jung et al. [58]. There is growing recognition that electricity is a commodity, and that what we call “quality energy” is simply a definition of the offered items’ features and their specified value in use. There are several terminologies that can be used to describe how electricity is treated in terms of energy quality. Electric energy is a commodity that is sold to a prospective consumer in order for them to obtain a decent product in a form that meets their needs. It has a set of unique features that, if they are not good enough, could hurt the user’s things or even their health [61,62][61][62]. Although rapid advancements in all fields have raised society’s living standards throughout time, they have also made customers, who are compelled to pick between a variety of services and product options, the main focus of organizational activity. Today, establishing a long-term marketing relationship with customers who are growing increasingly smart and have preferences as a result of their experiences is becoming increasingly difficult for businesses. Other than service quality, which is related to what is delivered and how it is presented to customers, researchers have recently emphasized the notion of value, which symbolizes the difference between advantages and the amount of benefit provided to the client. As a result, the client perceives the value of services rendered in the same way that he or she perceives the quality of those services [63,64,65][63][64][65]. When it comes to the quality of services and service procedures supplied in customer interactions, there are many factors that influence the construction of a customer’s perception. When a consumer compares the benefits and costs of services given to the benefits and costs offered by competitors, the value presented to the customer is developed [66,67][66][67]. As a result, to gain a competitive advantage by providing value to customers, you need to be different and better than your competitors in a lot of different ways, such as with your services, processes, systems, quality, speed, and so on. To accomplish this, innovations in services, service processes, and managerial procedures, as well as the continuation of such innovations, are required [65]. With the recognition of the necessity of providing customers with value, customer value has become a management tool in the development of service operations [68]. The scientific literature says that in order for a business to compete successfully, it needs to be able to provide value to the customer that its competitors cannot [69,70][69][70]. According to experts [71[71][72][73][74][75],72,73,74,75], customer value is the key tool of competitive strategies and at the heart of management techniques. Furthermore, customer value is intimately tied to an organization’s marketing approach and customer-oriented attitude [72,76][72][76]. The organization’s marketing activities revolve around the creation of value and its presentation to customers. Although there is no consensus in the literature on how to define “value” and its underlying dimensional meanings, the term is most commonly employed in “customer value”, “perceived value”, or simply “value” forms [77]. Customer value is the gap between the sum of a customer’s expectations for a product or service and the overall costs that they must incur in order to use that product or service [78]. The difference between the overall benefit acquired from a product or service and the whole expense required to obtain that product or service is known as customer value [79]. The customer value will be determined by the customer’s impression that the degree of service quality exceeds the fee paid for that service (cost). On the other hand, one cannot speak of a value offering to a consumer if the costs incurred are regarded to be higher than the level of services delivered [80,81][80][81]. The greater an organization’s understanding of consumer demands, the greater its competitive advantage [82]. The 2019 coronavirus disease pandemic (COVID-19) has had serious short- and long-term economic and societal consequences. It has also had a big impact on customer attitudes and behavior when it comes to purchasing [83]. There is no empirical research on what value and quality imply for energy market consumers or what factors influence the quality and value of energy market customers. The value-creation process should include a wide range of customer participation since their differing perspectives on expected value may “enrich” existing processes with resources not yet available to the supplier. Developing, maintaining, and improving relationships within client relationships creates new opportunities for mutually beneficial value generation [84,85][84][85]. In order for a product or service to be valuable, it has to have good resources [86,87][86][87]. A client is an organization or a person who gets a product, according to the PN-EN ISO 9000 standard [88]. The guidelines also highlight that businesses rely on their customers, so it is advised that they understand their customers’ current and future needs, meet their criteria, and strive to surpass their expectations. As a result, the client not only chooses the organization based on its financial results but also on its competitive position and image [89]. The quality management model (QMS) ISO 9001:2015 outlined in the standard implies that all processes carried out by the organization have a client at both the entrance and exit. Customer needs should be looked at as the input data, and customer satisfaction should be the output value [90,91][90][91] (Figure 1). The ISO 9001:2015 standard specifies that the business should treat the customer as the most significant entity, with the customer playing the most important part in the process of improving the quality of products and services [93]. Customer satisfaction in power distribution services is often assessed by technical performance, such as electricity availability [94,95][94][95]. The majority of these enterprises are focused on supplying power rather than achieving client expectations. However, in energy distribution services, service quality is a critical component, and customers are vulnerable to several elements of service quality [96,97,98][96][97][98]. The business evaluates all new client requirements to determine whether or not they can be met [99]. As a result, customer orientation is the bedrock upon which a company can establish a long-term competitive advantage [100]. The proposed customer value model by [101] tries to conceptualize how firms and customers perceive the value of a product or service, as well as identify value gaps. This paradigm, which pertains to a new era of the service business, allows us to better grasp value from both the customer’s and the company’s perspectives. Authors [100,102][100][102] have created a customer-based value model.References

- Kanwal, M.; Khan, H. Does carbon asset add value to clean energy market? Evidence from EU. Green Financ. 2021, 3, 495–507.

- Serem, N.; Letting, L.K.; Munda, J. Voltage Profile and Sensitivity Analysis for a Grid Connected Solar, Wind and Small Hydro Hybrid System. Energies 2021, 14, 3555.

- Uzir, M.U.H.; Jerin, I.; Al Halbusi, H.; Hamid, A.B.A.; Latiff, A.S.A. Does quality stimulate customer satisfaction where perceived value mediates and the usage of social media moderates? Heliyon 2020, 6, e05710.

- Jackson, L.A. Women and Work Culture: Britain c.1850–1950; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 9781351872089.

- Kelly, S.; Marshall, D.; Walker, H.; Israilidis, J. Supplier satisfaction with public sector competitive tendering processes. J. Public Procure. 2021, 21, 183–205.

- Hoda, R.; Noble, J.; Marshall, S. The impact of inadequate customer collaboration on self-organizing Agile teams. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2011, 53, 521–534.

- Lim, B.; Yoo, J.; Hong, K.; Cheong, I. Impacts of Reverse Global Value Chain (GVC) Factors on Global Trade and Energy Market. Energies 2021, 14, 3417.

- Słupik, S.; Kos-Łabędowicz, J.; Trzęsiok, J. An Innovative Approach to Energy Consumer Segmentation—A Behavioural Perspective. The Case of the Eco-Bot Project. Energies 2021, 14, 3556.

- Carrigan, M.; Attalla, A. The myth of the ethical consumer—Do ethics matter in purchase behaviour? J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 560–578.

- Toti, J.F.; Moulins, J.L. How to measure ethical consumption behaviors? RIMHE Rev. Interdiscip. Manag. Homme Entrep. 2016, 245, 45–66.

- Micheletti, M. Political Virtue and Shopping: Inviduals, Consumerism, and Collective Action; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2003.

- Kovanoviene, V.; Romeika, G.; Baumung, W. Creating Value for the Consumer Through Marketing Communication Tools. J. Compet. 2021, 13, 59–75.

- Peter, J.J.; Batonda, G. Effect of service quality on customer satisfaction in Tanzanian energy industry: A case of TANESCO residential customers in Nyamagana District. Int. J. Eng. Bus. Manag. 2022, 6, 47–59.

- Gunawan, H.; Prasetyo, J.H. The Influence of Service Quality towards the Customer Satisfaction of XYZ Bank at Gajah Mada Branch Office in West Jakarta. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. Technol. 2020, 5, 160–164.

- Cenamor, J. Complementor competitive advantage: A framework for strategic decisions. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 335–343.

- Bashan, A.; Kordova, S. Globalization, quality and systems thinking: Integrating global quality Management and a systems view. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06161.

- Erlangga, H.; Erlangga, H. Did Brand Perceived Quality, Image Product And Place Convenience Influence Customer Loyalty Through Unique Value Proposition? J. Contemp. Issues Bus. Gov. 2021, 27, 2854–2867.

- Carvalho, A.V.; Enrique, D.V.; Chouchene, A.; Charrua-Santos, F. Quality 4.0: An Overview. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2021, 181, 341–346.

- Wang, R.; Ke, C.; Cui, S. Product Price, Quality, and Service Decisions Under Consumer Choice Models. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2022, 24, 430–447.

- Christou, I.T.; Kefalakis, N.; Soldatos, J.K.; Despotopoulou, A.-M. End-to-end industrial IoT platform for Quality 4.0 applications. Comput. Ind. 2022, 137, 103591.

- Wang, H.; Xiang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Tang, Z.; Guo, J.; Zhang, X.; Hou, X.; Wang, H.; Cheng, M.; Li, Z. Responses of yield, quality and water-nitrogen use efficiency of greenhouse sweet pepper to different drip fertigation regimes in Northwest China. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 260, 107279.

- Esakova, K.D. Customer Relationship Management as A Modern Organization Management on the Example of the Nike Company. In Tpaнcφopмaция Экoнoмики И Упpaвлeния: Hoвыe Bызoвы И Пepcпeктивы; 2021; Available online: https://elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=45799977 (accessed on 18 April 2022).

- Horner, K.T. The Client-Centered Law Firm: How to Succeed in an Experience-Driven World. Blue Check Publishing. 2021. Available online: https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/naela17&div=8&id=&page= (accessed on 18 April 2022).

- Zhou, B.H.; Gu, J. Energy-awareness scheduling of unrelated parallel machine scheduling problems with multiple resource constraints. Int. J. Oper. Res. 2021, 41, 196–217.

- Fouad, M.M.; Kanarachos, S.; Allam, M. Perceptions of consumers towards smart and sustainable energy market services: The role of early adopters. Renew. Energy 2022, 187, 14–33.

- Blass, M.; Krebs, F.; Amon, C.; Adler, M.; Zirkl, M.; Tschepp, A.; Graf, F. Acoustic monitoring using PyzoFlex®: A novel printed sensor for smart consumer products. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1896, 12022.

- Zhukovskiy, Y.L.; Batueva, D.E.; Buldysko, A.D.; Gil, B.; Starshaia, V.V. Fossil Energy in the Framework of Sustainable Development: Analysis of Prospects and Development of Forecast Scenarios. Energies 2021, 14, 5268.

- Walsh, J. The Dynamics of the Social Worker-Client Relationship; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021; ISBN 9780197517956.

- Change Management in a VUCA World. In Visionary Leadership in a Turbulent World; Pearse, N.J. (Ed.) Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2017.

- Nowacka, A.; Rzemieniak, M. The Impact of the VUCA Environment on the Digital Competences of Managers in the Power Industry. Energies 2022, 15, 185.

- Liu, W.; Ma, Q.; Liu, X. Research on the dynamic evolution and its influencing factors of stock correlation network in the Chinese new energy market. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 45, 102138.

- Oostra, M.; Nelis, N. Concerns of Owner-Occupants in Realising the Aims of Energy Transition. Urban Plan. 2022, 7, 45–57.

- Pietrzak, M.B.; Igliński, B.; Kujawski, W.; Iwański, P. Energy Transition in Poland—Assessment of the Renewable Energy Sector. Energies 2021, 14, 2046.

- Jasiński, J.; Kozakiewicz, M.; Sołtysik, M. Determinants of Energy Cooperatives’ Development in Rural Areas—Evidence from Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 319.

- Kamyk, J.; Kot-Niewiadomska, A.; Galos, K. The criticality of crude oil for energy security: A case of Poland. Energy 2021, 220, 119707.

- Igliński, B.; Skrzatek, M.; Kujawski, W.; Cichosz, M.; Buczkowski, R. SWOT analysis of renewable energy sector in Mazowieckie Voivodeship (Poland): Current progress, prospects and policy implications. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 77–111.

- Adamek, A. Mikrosieci a otoczenie formalno-prawne w Polsce. Rynek Energii 2021, 6, 19–21.

- Żywiołek, J.; Rosak-Szyrocka, J.; Khan, M.A.; Sharif, A. Trust in Renewable Energy as Part of Energy-Saving Knowledge. Energies 2022, 15, 1566.

- Knez, M.; Jereb, B.; Jadraque Gago, E.; Rosak-Szyrocka, J.; Obrecht, M. Features influencing policy recommendations for the promotion of zero-emission vehicles in Slovenia, Spain, and Poland. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2020, 1–16.

- Gostin, L.O.; Parmet, W.E.; Rosenbaum, S. The US Supreme Court’s Rulings on Large Business and Health Care Worker Vaccine Mandates: Ramifications for the COVID-19 Response and the Future of Federal Public Health Protection. JAMA 2022, 327, 713–714.

- Mathur, N.; Tiwari, S.C.; Sita Ramaiah, T.; Mathur, H. Capital structure, competitive intensity and firm performance: An analysis of Indian pharmaceutical companies. Manag. Financ. 2021, 47, 1357–1382.

- Chen, C.; Nelson, H.; Xu, X.; Bonilla, G.; Jones, N. Beyond technology adoption: Examining home energy management systems, energy burdens and climate change perceptions during COVID-19 pandemic. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 145, 111066.

- Wydawnictwo UMCS. Jakość i Efektywność (Quality and Effectiveness); Wydawnictwo UMCS: Lublin, Poland, 2000.

- Popescu, D.-M.; Duta, N.M. Quality Leaders and Quality Management. In Proceedings of the International Conference Global Interferences of Knowledge Society, Targoviste, Romania, 16–17 November 2018; LUMEN Publishing House: Iasi, Romania, 2019; pp. 213–222.

- Permana, A.; Purba, H.H.; Rizkiyah, N.D. A systematic literature review of Total Quality Management (TQM) implementation in the organization. Int. J. Prod. Manag. Eng. 2021, 9, 25.

- Helmold, M. Statistical, Quality and Resource Management Tools. In Successful Management Strategies and Tools; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 71–79.

- Chen, C.-K.; Reyes, L.; Dahlgaard, J.; Dahlgaard-Park, S.M. From quality control to TQM, service quality and service sciences: A 30-year review of TQM literature. Int. J. Qual. Serv. Sci. 2021, 14.

- Grossu-Leibovica, D.; Kalkis, H. Total quality management tools and techniques for improving service quality and client satisfaction in the healthcare environment: A qualitative systematic review. SHS Web Conf. 2022, 131, 2009.

- Dahlgaard, J.J.; Anninos, L.N. Quality, resilience, sustainability and excellence: Understanding LEGO’s journey towards organisational excellence. Int. J. Qual. Serv. Sci. 2022, ahead-of-print.

- Basli, Z.; Matzen, D.R.; Abu, S.M. Formative Evaluation of Teaching Analysis (FETA) Using the SERVQUAL Scale: A Route to Students Satisfaction and Continuous Improvement. J. Sains Sos. Dan Pendidik. Tek.|J. Soc. Sci. Tech. Educ. (JoSSTEd) 2021, 2, 76–85.

- Craig, J.H.; Lemon, M. Perceptions and reality in quality and environmental management systems. TQM J. 2008, 20, 196–208.

- Isaksson, R.; Garvare, R. Measuring sustainable development using process models. Manag. Audit. J. 2003, 18, 649–656.

- Suprapto, W.; Stefany, S.; Ali, S. Service Quality, Store Image, Price Consciousness, and Repurchase Intention on Mobile Home Service. SHS Web Conf. 2020, 76, 1056.

- Beneke, J.; Flynn, R.; Greig, T.; Mukaiwa, M. The influence of perceived product quality, relative price and risk on customer value and willingness to buy: A study of private label merchandise. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2013, 22, 218–228.

- Bu, X.; Nguyen, H.V.; Chou, T.P.; Chen, C.-P. A Comprehensive Model of Consumers’ Perceptions, Attitudes and Behavioral Intention toward Organic Tea: Evidence from an Emerging Economy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6619.

- Mostafa, R.H.; Elseidi, R.I. Factors affecting consumers’ willingness to buy private label brands (PLBs). Span. J. Mark.-ESIC 2018, 22, 338–358.

- Yu, M.; Liu, F.; Lee, J.; Soutar, G. The influence of negative publicity on brand equity: Attribution, image, attitude and purchase intention. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2018, 27, 440–451.

- Jung, H.J.; Choi, Y.J.; Oh, K.W. Influencing Factors of Chinese Consumers’ Purchase Intention to Sustainable Apparel Products: Exploring Consumer “Attitude–Behavioral Intention” Gap. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1770.

- Mowen, J.C.; Minor, M. Perilaku Konsumen. Jkt. Erlangga 2002, 90, 16–37.

- Kato, T.; Tsuda, K. A Management Method of the Corporate Brand Image Based on Customers’ Perception. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2018, 126, 1368–1377.

- Wessel, J.; Turetskyy, A.; Cerdas, F.; Herrmann, C. Integrated Material-Energy-Quality Assessment for Lithium-ion Battery Cell Manufacturing. Procedia CIRP 2021, 98, 388–393.

- Nakajima, Y.; Matsushima, J. Japan’s Low-growth Economy from the Viewpoint of Energy Quality. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2022, 12, 460–468.

- Tuncer, I.; Unusan, C.; Cobanoglu, C. Service Quality, Perceived Value and Customer Satisfaction on Behavioral Intention in Restaurants: An Integrated Structural Model. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2021, 22, 447–475.

- Fischer, E.F. Quality and inequality: Creating value worlds with Third Wave coffee. Socioecon Rev. 2021, 19, 111–131.

- Yaşlıoğlu, M.; Çalışkan, B.Ö.Ö.; Şap, Ö. The Role of Innovation and Perceived Service Quality in Creating Customer Value: A Study on Employees of a Call Center Establishment. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 99, 629–635.

- Rademakers, M. Creating the Creating Value Academy. J. Creat. Value 2021, 7, 141–144.

- Żywiołek, J.; Rosak-Szyrocka, J.; Mrowiec, M. Knowledge Management in Households about Energy Saving as Part of the Awareness of Sustainable Development. Energies 2021, 14, 8207.

- Olaru, D.; Purchase, S.; Peterson, N. From customer value to repurchase intentions and recommendations. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2008, 23, 554–565.

- Grassl, W. Strategic Brand Management: Building, Measuring, and Managing Brand Equity. J. Consum. Mark. 2000, 17, 263–272.

- Malik, M.E.; Ghafoor, M.M.; Hafiz, K.; Ahmad, B.; Nisar, Q.A.; Hunbal, H.; Noman, M.; Ahmad, B. Impact of brand image and advertisement on consumer buying behavior. World Appl. Sci. J. 2013, 23, 117–122.

- Fortuin, F.T.J.M.; Omta, S.W.F. Aligning R&D To Business—A Longitudinal Study Of Bu Customer Value In R&D. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Manag. 2007, 04, 393–413.

- Brennan, R.; Henneberg, S.C. Does political marketing need the concept of customer value? Mark. Intell. Plan. 2008, 26, 559–572.

- Sánchez-Gutiérrez, J.; Cabanelas, P.; Lampón, J.F.; González-Alvarado, T.E. The impact on competitiveness of customer value creation through relationship capabilities and marketing innovation. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2019, 34, 618–627.

- Chasin, F.; Paukstadt, U.; Ullmeyer, P.; Becker, J. Creating Value From Energy Data: A Practitioner’s Perspective on Data-Driven Smart Energy Business Models. Schmalenbach Bus. Rev. 2020, 72, 565–597.

- Triandewo, M.A.; Dewantoro, W. The Impact of Customer Value, Price, Brand Image and Service Quality on Customer Satisfaction on XL Prepaid Card 4G Network in Bekasi City. J. Orientasi Bisnis Dan Entrep. 2021, 2, 108–121.

- Daim, T.U.; Oliver, T.; Phaal, R. (Eds.) Culture. In Technology Roadmapping; World Scientific: Singapore, 2018; pp. 29–63. ISBN 978-981-12-2832-2.

- Howden, C.; Pressey, A.D. Customer value creation in professional service relationships: The case of credence goods. Serv. Ind. J. 2008, 28, 789–812.

- Kotler, P.; Pfoertsch, W.; Sponholz, U. The Current State of Marketing. In H2H Marketing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–28.

- van Boerdonk, P.; Krikke, H.R.; Lambrechts, W. New business models in circular economy: A multiple case study into touch points creating customer values in health care. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 282, 125375.

- Uzir, M.U.H.; Al Halbusi, H.; Thurasamy, R.; Thiam Hock, R.L.; Aljaberi, M.A.; Hasan, N.; Hamid, M. The effects of service quality, perceived value and trust in home delivery service personnel on customer satisfaction: Evidence from a developing country. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 63, 102721.

- He, J.; Zhang, S. How digitalized interactive platforms create new value for customers by integrating B2B and B2C models? An empirical study in China. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 142, 694–706.

- Wu, Y.-L.; Li, E.Y. Marketing mix, customer value, and customer loyalty in social commerce. Internet Res. 2018, 28, 74–104.

- Liang, L.; Wu, G. Effects of COVID-19 on customer service experience: Can employees wearing facemasks enhance customer-perceived service quality? J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 50, 10–20.

- Mukai, T.; Nishio, K.; Komatsu, H.; Sasaki, M. What effect does feedback have on energy conservation? Comparing previous household usage, neighbourhood usage, and social norms in Japan. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 86, 102430.

- Rosak-Szyrocka, J.; Abbas, A.A.; Akhtar, H.; Refugio, C. Employment and Labour Market Impact of COVID-19 Crisis-Part 1–Analysis in Poland. Syst. Saf.: Hum.-Tech. Facil.-Environ. 2021, 3, 108–115.

- Prasetyo, Y.T.; Tanto, H.; Mariyanto, M.; Hanjaya, C.; Young, M.N.; Persada, S.F.; Miraja, B.A. Redi, Anak Agung Ngurah Perwira. Factors Affecting Customer Satisfaction and Loyalty in Online Food Delivery Service during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Its Relation with Open Innovation. JOItmC 2021, 7, 76.

- Rigo, P.D.; Siluk, J.C.M.; Lacerda, D.P.; Spellmeier, J.P. Competitive business model of photovoltaic solar energy installers in Brazil. Renew. Energy 2022, 181, 39–50.

- Wąsikiewicz-Rusnak, U. Integrated management of the iso 9000, iso 14000 and pn-n 18001 systems of standards at a selected enterprise. Econ. Environ. Stud. 2008, 11, 203–209.

- Tebar Betegon, M.A.; Baladrón González, V.; Bejarano Ramírez, N.; Martínez Arce, A.; Rodríguez De Guzmán, J.; Redondo Calvo, F.J. Quality Management System Implementation Based on Lean Principles and ISO 9001:2015 Standard in an Advanced Simulation Centre. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2021, 51, 28–37.

- Kim, C.; Chung, K. Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Hotel Efficiency Analysis: An Approach Based on Data Envelopment Analysis. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2022, 63, 257–266.

- Amenuvor, F.E.; Basilisco, R.; Boateng, H.; Shin, K.S.; Im, D.; Owusu-Antwi, K. Salesforce output control and customer-oriented selling behaviours. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2022, 40, 344–357.

- Kaniecka, E.; Timler, D.; Białas, A.; Timler, M.; Białas, M.; Staszewska, A.; Rybarczyk-Szwajkowska, A. EN ISO 9001: 2015 Quality Management System for Health Care Sector in Accordance with PN-EN 15224: 2017-02 Standard and Accreditation Standards of the Minister of Health–Comparative Analysis. J. Health Study Med. 2021, 1, 41–62.

- Ikram, M.; Zhang, Q.; Sroufe, R. Future of quality management system (ISO 9001) certification: Novel grey forecasting approach. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2021, 32, 1666–1693.

- Anwar, M.B.; Muratori, M.; Jadun, P.; Hale, E.; Bush, B.; Denholm, P.; Ma, O.; Podkaminer, K. Assessing the value of electric vehicle managed charging: A review of methodologies and results. Energy Environ. Sci. 2022, 15, 466–498.

- Miao, R.; Guo, P.; Huang, W.; Li, Q.; Zhang, B. Profit model for electric vehicle rental service: Sensitive analysis and differential pricing strategy. Energy 2022, 249, 123736.

- Chen, Z.; Chen, X.; Mak, B. The hybrid discourse on creative tourism: Illuminating the value creation process. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2021, 15, 547–564.

- Heng, L.; Yin, G.; Zhao, X. Energy aware cloud-edge service placement approaches in the Internet of Things communications. Int. J. Commun. Syst. 2022, 35, e4899.

- Shi, E.; Zhang, J.; Chen, S.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ng, D.W.K.; Ai, B. Wireless Energy Transfer in RIS-Aided Cell-Free Massive MIMO Systems: Opportunities and Challenges. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2201.11302.

- Demir, A. Inter-continental review for diffusion rate and internal-external benefits of ISO 9000 QMS. Int. J. Product. Qual. Manag. 2021, 33, 336–366.

- Tsuchiya, H.; Fu, Y.-M.; Huang, S.C.-T. Customer value, purchase intentions and willingness to pay: The moderating effects of cultural/economic distance. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2022, 34, 268–286.

- Moist, J.A.; Anitsal, I.; Anitsal, M.M. The Customer Value Model and Mobile Banking: Evaluation of Technology-Based Self Service (TBSS) Gaps. Atl. Mark. J. 2021, 10, 2.

- Wang, N.; Hu, D.; Xu, J.; Zhao, J. Time-dependent Vehicle Routing of Urban Cold-chain Logistics Based on Customer Value and Satisfaction. China J. Highw. Transp. 2021, 34, 297–308.

More