The global prevalence of nutraceuticals is reflected in the increasing number of commercially available nutraceuticals and their wide range of applications. Therefore, a unique opportunity emerges for their further exploration using innovative, reliable, accurate, low cost, and high hit rate methods to design and develop next generation nutraceuticals. Towards this direction, computational techniques constitute an influential trend for academic and industrial research, providing not only the chemical tools necessary for further mechanism characterization but also the starting point for the development of novel nutraceuticals.

- nutraceuticals

- natural products

- in cilico

- chemolibraries

- drug delivery

- nanonutraceuticals

- in silico

1. Introduction

Nutraceuticals constitute an emerging sector in the pharmaceutical and food industry, receiving considerable interest due to their functions [1]. Several nutraceuticals are promising agents for the prevention and treatment of various diseases, such as allergies, Alzheimer’s disease, cardiovascular and eye disorders, cancer, obesity, diabetes, and Parkinson’s disease, as well as the regulation of immune system function and inflammation [2]. Based on the increasing number of commercially available nutraceuticals and their wide range of applications, the global nutraceutical market accounted for $289.8 billion in the year 2021 and is expected to grow to $438.9 billion by the year 2026, with a compound annual growth rate of 8.7% for the aforementioned period [3]. Furthermore, following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the nutraceutical market is expected to increase due to the possible beneficial effects of these products on the human immune system function [4]. Additionally, the number of nutraceutical-based patents has increased, highlighting the crucial role of nutraceuticals worldwide [5].

Currently, the nutraceutical industry conforms to the practices of conventional food or pharmaceutical technology. However, current advances in the field of nanotechnology are the driving force behind the novel research strategies followed in nutraceutical development. Presently, nanosystems (structures or molecules of at least one dimension with a size from 1 to 100 nm) are incorporated in many different areas of food and health sciences. For instance, nanoengineered materials have been applied (a) for the nanopacking and improvement of the sensory attributes of foods, (b) for the smart delivery and nanofortification of functional and fortified products, and (c) for personalized treatment in nanomedicine [6]. The implementation of nano-scale materials for the encapsulation and delivery of nutraceuticals coined the concept of nanonutraceuticals [7].

2. Nutraceuticals

2.1. Nutraceuticals: Definition and Introduction

2.2. Nutraceuticals Classification

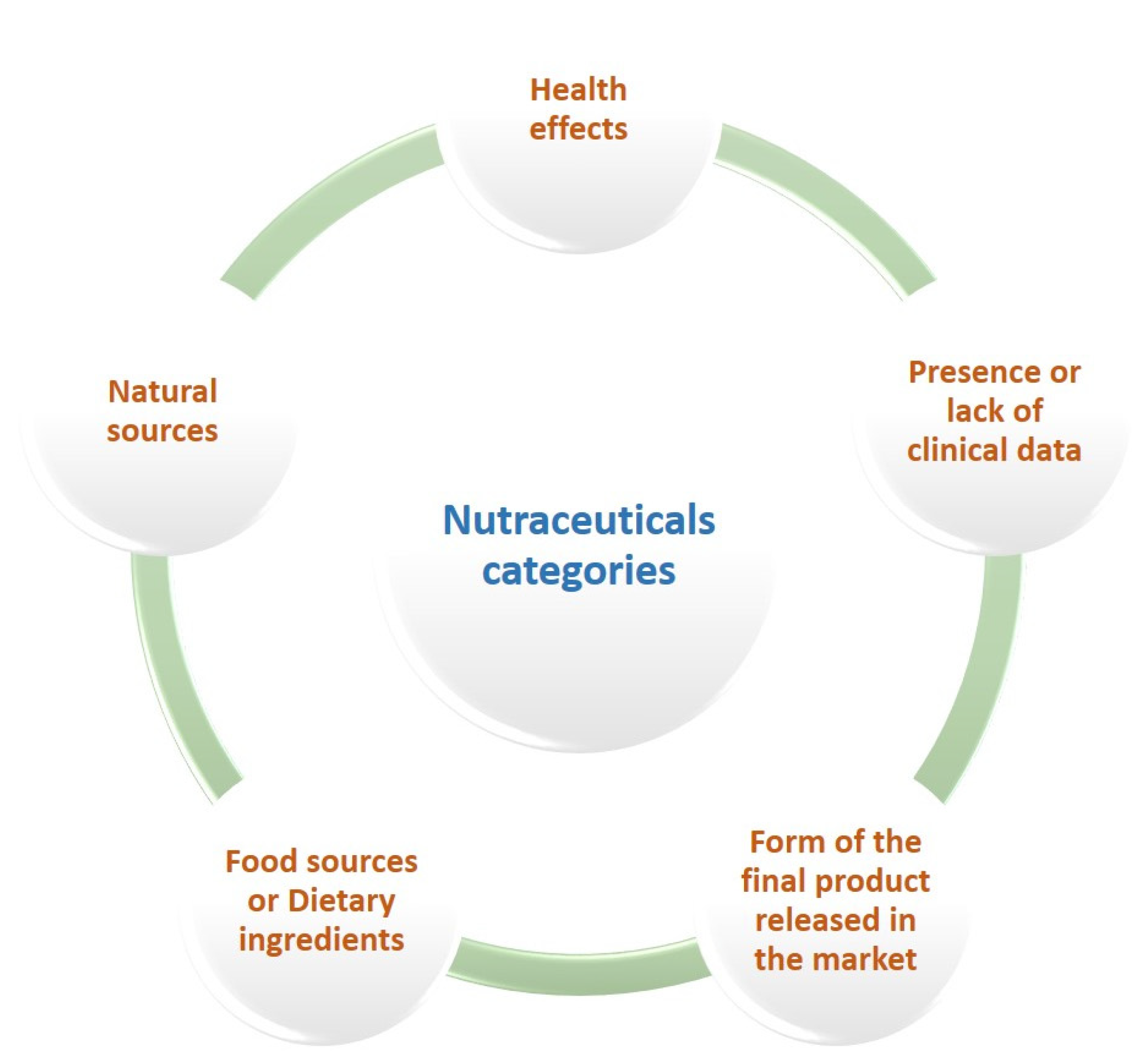

Since no scientific consensus has been reached yet over the classification of nutraceuticals, various criteria have been applied for their categorization (Figure 1). The key categories of nutraceuticals are herbal and botanical products (natural extracts or concentrates), nutrients (fatty acids, amino acids, vitamins, and minerals), functional foods, and dietary supplements, while their major natural sources are animals, plants, and microbes. If classified as nutritional ingredients, they can be divided into probiotics, prebiotics, antioxidant vitamins, polyunsaturated fatty acids, dietary fibers, polyphenols, and carotenoids [12]. Tablets, pills, creams, capsules, liquids, and powders are the most common forms touted in the global market [13]. On the basis of their health benefits, nutraceuticals serve several functions against various ailments, such as neurodegenerative and cardiovascular diseases, metabolic syndromes, congenital abnormalities, bone-related pathologies (osteoarthritis, osteoporosis), and cancer [13][14]. The term ‘established nutraceuticals’ includes the products with confirmed health-promoting effects, while the lack of validated clinical evidence describes the group of ‘potential nutraceuticals’ [12].

3. Novel Approaches in Nutraceuticals’ Discovery

3.1. Natural Products (NPs) Databases (Chemo-Libraries)

The ZINC 15 database (http://zinc15.docking.org, accessed on 11 April 2022) constitutes the most comprehensive resource, which includes readily purchasable compounds (over 230 million compounds in a ready-to-dock format), overcoming the limitations of the compounds’ commercial availability. Particularly, the field of natural compounds consists of over 80,000 ready-to-use compounds, derived from a plethora of vendors.

Analyticon Discovery (https://ac-discovery.com/, accessed on 11 April 2022) is a free access database, that provides a continuously growing collection of purified natural compounds. In particular, the library could be divided into the following subsets: (a) MEGx which offers about 5000 purified natural compounds originating from plants and microorganisms, (b) MACROx comprises over of 1800 macrocycle compounds, and (c) FRGx with over 200 fragments.

Ambinter (https://www.ambinter.com/, accessed on 11 April 2022) and Greenpharma (www.greenpharma.com, accessed on 11 April 2022) constitute two collaborative companies, offering a set of ~8000 natural compounds (alkaloids, phenols, phenolic acids, terpenoids, and others) in .SDF format ready to use for virtual screening. Additionally, the above-mentioned companies propose more than 11,000 semi-synthetic derivatives of natural compounds [27]. One of the largest natural compound libraries is InterBioScreen (https://www.ibscreen.com/, accessed on 11 April 2022), listing over 68,000 well-annotated natural compounds derived from a variety of sources, such as plants and microorganisms. The presented library is easily and quickly downloaded in a readable format (.SMILES and .SDF) [27]. The MolPort (https://www.molport.com/, accessed on 11 April 2022) database is another natural compound vendor of paramount importance since it stores in downloadable files over 10,000 unique natural and over 100,000 natural-like products from a variety of suppliers (.SMILES and .SDF). Therefore, its usage facilitates in silico screening applications since it possesses available-to-purchase natural products. A collection of more than 3000 natural compounds and 396 food additive-related compounds are supplied from MedChemExpress (https://www.medchemexpress.com/, accessed on 11 April 2022). For data accessibility, a query is required, and purchasable compounds in .SDF format is received. The main advantage of the present database is that all compounds have indicated bioactivity and safety. INDOFINE Chemical Company (https://indofinechemical.com/, accessed on 11 April 2022) includes around 1900 NPs and semisynthetic compounds, in a ready-to-screen format (.SDF), focused on flavonoids. The library consists of flavonoids, flavones, isoflavones, flavanones, coumarins, chromones, chalcones, and lipids especially. The chemical scaffolds of Indofine are offered and are classified according to compound types.3.2. Virtual Screening (VS) Techniques

As it is generally known, the identification of bioactive molecules constitutes an expensive, time-consuming, and laborious inter-disciplinary process. As a result, innovative approaches are continuously developed, aiming to optimize and simplify this procedure. Among them, Virtual Screening (VS) is one of the most important and widespread strategies that has been applied for the determination of potentially bioactive molecules. In recent years, a variety of tools and software that can be performed in VS were utilized to reduce the selection of promising compounds that will be tested experimentally. Particularly, VS objectives are to accelerate the discovery process, increase the number of compounds to be tested experimentally, and rationalize their choice [28][29]. Additionally, the classification of NPs into libraries contributes effectively to VS, facing and tackling issues related to the extraction, purification, and purchasability of NPs [27]. The most commonly used methods for VS of NP libraries include Molecular Docking, Quantitative Structure-Activity Models (QSAR), Molecular Docking, Pharmacophore Modeling, and Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations. The main advantage of these methods is that they lead to reducing the selection of compounds that will be tested experimentally [30]. Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) In general, Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) analysis is a ligand-based computational technique that attempts to correlate the structural properties (chemical structures) and the biological activity of a compounds’ dataset [31]. The underlying principle of QSAR models is based on the hypothesis that structurally similar compounds may exhibit similar biological activities [32]. The creation of QSAR models is causally linked with equations that relate a dependent variable (i.e., an observed activity) with a number of calculated descriptors, including physicochemical, constitutional, and topological properties [33][34]. For this purpose, various multivariate statistical regression (Multiple Linear Regression—MLR, Principal Component Analysis—PCA, and Partial Least Square Analysis—PLS) and Machine Learning (ML) tools are applied in an effort to generate appropriate algorithms [35]. Table 3 presents a list of available software for molecular descriptor calculations. The building of the model is followed by the validation process in which the accuracy of the method is verified. The produced model can be used as a prediction tool to prioritize compounds that have the potential to display biological activity and to reduce the number of the compounds that will be tested experimentally [36]. Therefore, it is a widely used process with a broad spectrum of applications in the pharmaceutical landscape [37]. Regarding nutraceuticals, the relationship between food ingredients and a variety of properties has already been studied on several occasions [38]. Molecular Docking Molecular Docking is the most commonly used in silico technique, which predicts the interaction between a small molecule (ligand) and a protein (receptor) at the atomic level. This approach enables the characterization of the behavior of small molecules in the binding site of a target protein as well as the elucidation of the fundamental biochemical process behind this interaction [39]. It is a structure-based approach which requires a high-resolution 3D illustration of the examined target derived from (a) X-ray crystallography [40], (b) Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy [41], and (c) Cryo-Electron Microscopy [42]. Pharmacophore Modeling A pharmacophore model illustrates in a 3D arrangement, the chemical features, which are crucial for the molecular recognition of a ligand by a macromolecule, offering a putative explanation for the binding affinity of structurally diverse ligands to a common target [43]. It can be generated either in a structure-based way, by predicting the potential interactions between the target and the ligand, or in a ligand-based way, by overlaying a group of active molecules and creating common chemical features that may be responsible for their bioactivity [44]. Currently, a variety of 3D pharmacophore modeling generators have been constructed, containing commercially available software and academic programs [45]. Molecular Dynamics Simulations (MD simulation) Molecular Dynamics Simulation is another powerful computational tool that captures the behavior of proteins, ligand-protein complexes, and other biomolecules in full atomic detail and at very fine temporal resolution [46]. It is a well-established technique which provides a molecular perspective to observe the behavior of atoms, molecules, and particulates [47]. Based on Newton’s equation of motion, MD predicts the physical movements of atoms and molecules using interatomic potentials or molecular mechanics force fields, offering the opportunity to comprehend the overall behavior of molecular systems during the motion of individual atoms [46]. Applications of in Silico Screening Techniques in the Field of Nutraceuticals Nowadays, the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), a life-threatening disease causing thousands of deaths daily, is responsible for a current global health crisis. Therefore, the scientific community has the made treatment and prevention of SARS-CoV-2 infection its first priority [48]. It has been proven that nutraceuticals contribute effectively to reducing the chances of SARS-CoV-2 infection, but also in alleviating COVID-19 symptoms [49]. Towards this direction, Gyebi et al. (2021) performed a structure-based virtual screening to suggest inhibitors of 3-Chymotrypsin-Like Protease (3CLpro) of SARS-CoV-2 from Vernonia amygdalina and Occinum gratissimum. In particular, they applied docking studies in the active site of 3CLpro, aiming to predict the binding affinity of an in-house library, which includes 173 phytochemicals from Vernonia amygdalina and Occinum gratissimum. Docking results defined a hit list of 10 phytochemicals with strong binding affinities in the catalytic center of 3CLpro from three related strains of coronavirus (SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and HKU4). Subsequently, drug-likeness prediction revealed two terpenoids, neoandrographolide and vernolide, as the most promising inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro. The selected compounds were subjected to Molecular Dynamics simulations and the results showed that the examined terpenoid-enzyme complexes exhibited strong interactions and structural stability, which could be adapted in experimental models for the development of preventive nutraceuticals against coronavirus diseases [50].4. Nanotechnology: A Powerful Toolbox in the Field of Nutraceuticals

4.1. Nanonutraceuticals

Nanonutraceuticals outweigh traditional nutraceutical formulations since they can (a) enhance the solubility and stability of the encapsulated natural bioactive compounds and (b) increase their absorption and biological efficacy by diminishing the off-target release and minimizing their side effects [7]. The up-to-date reported nanosized delivery systems include polymeric nanonutraceuticals (nanocapsules and nanospheres), carbon-based nanomaterials (i.e., fullerene and graphene particles), lipid-based formulations (solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs), lipid nanocapsules, micelles, nanosuspensions, lipid–polymer hybrid nanoparticles, nanostructured lipid carriers, and liposomes), metal-based nanoparticles (silver and gold nanoparticles), dendrimers, nanoemulsions, exosomes, niosomes, quantom dots, nanoshells, nanofilms, and nanofibers. In the majority of cases, the therapeutic cargo of these nanocarriers is attributed to biologically active constituents, such as minerals, vitamins, polyphenols (i.e., resveratrol, rutin, tannins, anthocyanins, catechins and flavonoids, curcuminoids, berberine, etc.), carotenoids (lycopene, β-carotene, astaxanthin, etc.), ω-3 fatty acids, phytosterols, and probiotics (Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium bacteria). When these nanovehicles are loaded with phytochemicals (i.e., curcumin, resveratrol, vitamin E, etc.), they are specified as nano-phytomedicines or nano-phytoceuticals. The first insights concerning these nanoformulations showed that they act as more efficient delivery systems of phytoconstituents [51][52]. Based on the latest scientific evidence, the role of nutraceuticals in the prevention and treatment of several pathologies is multifarious. The scope of health-related applications of nanonutraceuticals is extended from the display of antioxidant, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, wound healing, pain relief, and immunomodulatory properties to the management of age-related neurogenerative conditions (i.e., Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease), cancer, diabetes, skin diseases and recently, of pre- and post-COVID-19 infections [52][53]. Nonetheless, the research community should address some issues regarding the toxicity and safety implications as well as the manufacturing challenges of nanonutraceuticals. At first, these nanoformulations must be fully characterized on the basis of their physicochemical properties, especially their size and shape, which may induce tissue damage or inadvertent permeation of non-targeted cell membranes. In addition, further clinical data from in vivo animal models should be collected and evaluated to decipher the mechanisms of action of these nanoproducts, improve their absorption and metabolism by the gastroinstestinal (GI) tract, and eliminate any possible immunotoxicity. Furthermore, the commercialization of nanoproducts is strongly related to the establishment of scaled-up cost-effective processes, which ensure the reproducibility, reliability, and high quality of the final product. The outcomes of these trials will lead to the establishment of guidelines and standardized protocols for the safe monitoring of nanonutraceuticals, which, eventually, will curb the concerns of the consumers regarding their use [7][54].4.2. Nanonutraceuticals Applications

Indicative examples of the newest applications of nanoformulations, recorded in the last two years (2021–2022) are exhibited in Table 7.

| Nanonutraceuticals | Bioactive Compounds | Properties | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nanoemulsion of monoglyceride oleogels | Curcumin | Higher encapsulation efficiency/Decelerate curcumin release | [55] | |

| Nanoemulsion of PLGA and PVA natural polymers | Thymoquinone | Reduce cisplatin-induced kidney inflammation without hindering its anti-tumor activity | [56] | |

| Almond oil nanoemulsion | Thymoquinone | Gastroprotective activities | [57] | |

| α-Cyclodextrin nanoemulsion | Costunolide | Enhanced anticancer properties | [58] | |

| Oil-in-water nanoemulsions | Resveratrol | Improved solubility, bioavailability, in vivo efficacy, and cytotoxic activity | [59] | |

| Solid lipid nanoparticles | Berberine | Higher bioavailability and anticancer effect | [60] | |

| Ufasomes | Oleuropein | Higher antioxidant activity | [61] | |

| Liposomes | Thymoquinone | Reduced toxicity, increased cell absorption and permeability/enhanced bioavailability and anticancer efficacy | [62][63] | |

| Liposomes | Quercetin and mint oil | Protection against oral cavities | [64] | |

| Corn starch-sodium alginate nanofibers | Bifidobacteria | and lactic acid bacteria | Protection of their probiotic activity in a food model and a simulated gastrointestinal system | [65][66] |

| Food-derived hydrogel nanostructures | Lupin- and soybean glycinin-derived peptides | Antioxidant activity/ DPP-IV and ACE inhibitors | [67][68] | |

| Nanoparticles | Soy isoflavones | Activity against the neurogenerative effect of D-galactose | [69] |

References

- Dikmen, B.Y.; Filazi, A. Chapter 69—Nutraceuticals: Turkish Perspective. In Nutraceuticals; Gupta, R.C., Ed.; Academic Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 971–981.

- Nasri, H.; Baradaran, A.; Shirzad, H.; Rafieian-Kopaei, M. New Concepts in Nutraceuticals as Alternative for Pharmaceuticals. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2014, 5, 1487–1499.

- BCC Research. Nutraceuticals Market Size, Share & Growth Analysis Report. Available online: https://www.bccresearch.com/market-research/food-and-beverage/nutraceuticals-global-markets.html (accessed on 13 March 2022).

- Mordor Intelligence. Global Nutraceuticals Market Size, Share, Trends, Growth (2022–27). Available online: https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/global-nutraceuticals-market-industry (accessed on 13 March 2022).

- Daliu, P.; Santini, A.; Novellino, E. A Decade of Nutraceutical Patents: Where Are We Now in 2018? Expert Opin. Ther. Patents 2018, 28, 875–882.

- Aguilar-Pérez, K.M.; Ruiz-Pulido, G.; Medina, D.I.; Parra-Saldivar, R.; Iqbal, H.M. Insight of Nanotechnological Processing for Nano-Fortified Functional Foods and Nutraceutical—Opportunities, Challenges, and Future Scope in Food for Better Health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 1–18.

- Paolino, D.; Mancuso, A.; Cristiano, M.C.; Froiio, F.; Lammari, N.; Celia, C.; Fresta, M. Nanonutraceuticals: The New Frontier of Supplementary Food. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 792.

- Andlauer, W.; Fürst, P. Nutraceuticals: A Piece of History, Present Status and Outlook. Food Res. Int. 2002, 35, 171–176.

- De Felice, S.L. The Nutraceutical Revolution: Its Impact on Food Industry R&D. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 6, 59–61.

- Pandey, M.; Verma, R.; Saraf, S. Nutraceuticals: New Era of Medicine and Health. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2010, 3, 2010.

- Andrew, R.; Izzo, A.A. Principles of Pharmacological Research of Nutraceuticals. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 174, 1177–1194.

- Ansari, S.; Chauhan, B.; Kalam, N.; Kumar, G. Current Concepts and Prospects of Herbal Nutraceutical: A Review. J. Adv. Pharm. Technol. Res. 2013, 4, 4–8.

- De, S.; Gopikrishna, A.; Keerthana, V.; Girigoswami, A.; Girigoswami, K. An Overview of Nanoformulated Nutraceuticals and Their Therapeutic Approaches. Curr. Nutr. Food Sci. 2021, 17, 392–407.

- Blaze, J. A Comparison of Current Regulatory Frameworks for Nutraceuticals in Australia, Canada, Japan, and the United States. Innov. Pharm. 2021, 12, 8.

- Lagunin, A.A.; Goel, R.K.; Gawande, D.Y.; Pahwa, P.; Gloriozova, T.A.; Dmitriev, A.V.; Ivanov, S.M.; Rudik, A.V.; Konova, V.I.; Pogodin, P.V.; et al. Chemo- and Bioinformatics Resources for in Silico Drug Discovery from Medicinal Plants beyond Their Traditional Use: A Critical Review. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2014, 31, 1585–1611.

- Global Natural & Organic Personal Care Market 2018–2026: Growth Trends, Key Players and Competitive Strategies. Available online: https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/global-natural--organic-personal-care-market-2018-2026-growth-trends-key-players-and-competitive-strategies-300675255.html (accessed on 13 March 2022).

- Sorokina, M.; Merseburger, P.; Rajan, K.; Yirik, M.A.; Steinbeck, C. COCONUT Online: Collection of Open Natural Products Database. J. Cheminform. 2021, 13, 2.

- van Santen, J.A.; Jacob, G.; Singh, A.L.; Aniebok, V.; Balunas, M.J.; Bunsko, D.; Neto, F.C.; Castaño-Espriu, L.; Chang, C.; Clark, T.N.; et al. The Natural Products Atlas: An Open Access Knowledge Base for Microbial Natural Products Discovery. ACS Cent. Sci. 2019, 5, 1824–1833.

- Naveja, J.J.; Rico-Hidalgo, M.P.; Medina-Franco, J.L. Analysis of a Large Food Chemical Database: Chemical Space, Diversity, and Complexity. F1000Research 2018, 7, 993.

- Zeng, X.; Zhang, P.; Wang, Y.; Qin, C.; Chen, S.; He, W.; Tao, L.; Tan, Y.; Gao, D.; Wang, B.; et al. CMAUP: A Database of Collective Molecular Activities of Useful Plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D1118–D1127.

- Choudhary, A.; Naughton, L.M.; Montánchez, I.; Dobson, A.D.W.; Rai, D.K. Current Status and Future Prospects of Marine Natural Products (MNPs) as Antimicrobials. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 272.

- Pradhan, B.; Nayak, R.; Patra, S.; Jit, B.P.; Ragusa, A.; Jena, M. Bioactive Metabolites from Marine Algae as Potent Pharmacophores against Oxidative Stress-Associated Human Diseases: A Comprehensive Review. Molecules 2021, 26, 37.

- Ghosh, S.; Sarkar, T.; Pati, S.; Kari, Z.A.; Edinur, H.A.; Chakraborty, R. Novel Bioactive Compounds From Marine Sources as a Tool for Functional Food Development. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 832957.

- Khanam, S.; Prakash, A. Biomedical Applications and Therapeutic Potential of Marine Natural Products and Marine Algae. IP J. Nutr. Metab. Health Sci. 2021, 4, 76–82.

- Lyu, C.; Chen, T.; Qiang, B.; Liu, N.; Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Z. CMNPD: A Comprehensive Marine Natural Products Database towards Facilitating Drug Discovery from the Ocean. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D509–D515.

- Diallo, B.N.; Glenister, M.; Musyoka, T.M.; Lobb, K.; Tastan Bishop, Ö. SANCDB: An Update on South African Natural Compounds and Their Readily Available Analogs. J. Cheminform. 2021, 13, 37.

- Chen, Y.; de Bruyn Kops, C.; Kirchmair, J. Data Resources for the Computer-Guided Discovery of Bioactive Natural Products. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2017, 57, 2099–2111.

- Haga, J.H.; Ichikawa, K.; Date, S. Virtual Screening Techniques and Current Computational Infrastructures. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2016, 22, 3576–3584.

- da Silva Rocha, S.F.L.; Olanda, C.G.; Fokoue, H.H.; Sant’Anna, C.M.R. Virtual Screening Techniques in Drug Discovery: Review and Recent Applications. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2019, 19, 1751–1767.

- Lin, X.; Li, X.; Lin, X. A Review on Applications of Computational Methods in Drug Screening and Design. Molecules 2020, 25, 1375.

- Neves, B.J.; Braga, R.C.; Melo-Filho, C.C.; Moreira-Filho, J.T.; Muratov, E.N.; Andrade, C.H. QSAR-Based Virtual Screening: Advances and Applications in Drug Discovery. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1275.

- Akamatsu, M. Current State and Perspectives of 3D-QSAR. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2002, 2, 1381–1394.

- Rybińska-Fryca, A.; Sosnowska, A.; Puzyn, T. Representation of the Structure—A Key Point of Building QSAR/QSPR Models for Ionic Liquids. Materials 2020, 13, 2500.

- Roy, K.; Kar, S.; Das, R.N. Chemical Information and Descriptors. In Understanding the Basics of QSAR for Applications in Pharmaceutical Sciences and Risk Assessment; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 47–80.

- Dudek, A.Z.; Arodz, T.; Gálvez, J. Computational Methods in Developing Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships (QSAR): A Review. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen 2006, 9, 213–228.

- Cherkasov, A.; Muratov, E.; Fourches, D.; Varnek, A.; Baskin, I.; Cronin, M.; Dearden, J.; Gramatica, P.; Martin, Y.; Todeschini, R.; et al. QSAR Modeling: Where Have You Been? Where Are You Going To? J. Med. Chem. 2013, 57, 4977–5010.

- Achary, P.G.R. Applications of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships (QSAR) Based Virtual Screening in Drug Design: A Review. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2020, 20, 1375–1388.

- Pripp, A.H.; Isaksson, T.; Stepaniak, L.; Sørhaug, T.; Ardö, Y. Quantitative Structure Activity Relationship Modelling of Peptides and Proteins as a Tool in Food Science. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2005, 16, 484–494.

- Meng, X.Y.; Zhang, H.X.; Mezei, M.; Cui, M. Molecular Docking: A Powerful Approach for Structure-Based Drug Discovery. Curr. Comput. Aided Drug Des. 2011, 7, 146–157.

- Smyth, M.S.; Martin, J.H. X Ray Crystallography. Mol. Pathol. 2000, 53, 8–14.

- Sugiki, T.; Kobayashi, N.; Fujiwara, T. Modern Technologies of Solution Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy for Three-Dimensional Structure Determination of Proteins Open Avenues for Life Scientists. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2017, 15, 328–339.

- Nakane, T.; Kotecha, A.; Sente, A.; McMullan, G.; Masiulis, S.; Brown, P.M.G.E.; Grigoras, I.T.; Malinauskaite, L.; Malinauskas, T.; Miehling, J.; et al. Single-Particle Cryo-EM at Atomic Resolution. Nature 2020, 587, 152–156.

- Seidel, T.; Bryant, S.D.; Ibis, G.; Poli, G.; Langer, T. 3D Pharmacophore Modeling Techniques in Computer-Aided Molecular Design Using LigandScout. In Tutorials in Chemoinformatics; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 279–309.

- Yang, S.Y. Pharmacophore Modeling and Applications in Drug Discovery: Challenges and Recent Advances. Drug Discov. Today 2010, 15, 444–450.

- Schaller, D.; Šribar, D.; Noonan, T.; Deng, L.; Nguyen, T.N.; Pach, S.; Machalz, D.; Bermudez, M.; Wolber, G. Next Generation 3D Pharmacophore Modeling. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2020, 10, e1468.

- Hollingsworth, S.A.; Dror, R.O. Molecular Dynamics Simulation for All. Neuron 2018, 99, 1129–1143.

- Chen, G.; Huang, K.; Miao, M.; Feng, B.; Campanella, O.H. Molecular Dynamics Simulation for Mechanism Elucidation of Food Processing and Safety: State of the Art. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2019, 18, 243–263.

- Tagde, P.; Tagde, S.; Tagde, P.; Bhattacharya, T.; Monzur, S.M.; Rahman, M.H.; Otrisal, P.; Behl, T.; ul Hassan, S.S.; Abdel-Daim, M.M.; et al. Nutraceuticals and Herbs in Reducing the Risk and Improving the Treatment of COVID-19 by Targeting SARS-CoV-2. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1266.

- Savant, S.; Srinivasan, S.; Kruthiventi, A.K. Potential Nutraceuticals for COVID-19. Nutr. Diet. Suppl. 2021, 13, 25–51.

- Gyebi, G.A.; Elfiky, A.A.; Ogunyemi, O.M.; Ibrahim, I.M.; Adegunloye, A.P.; Adebayo, J.O.; Olaiya, C.O.; Ocheje, J.O.; Fabusiwa, M.M. Structure-Based Virtual Screening Suggests Inhibitors of 3-Chymotrypsin-Like Protease of SARS-CoV-2 from Vernonia Amygdalina and Occinum Gratissimum. Comput. Biol. Med. 2021, 136, 104671.

- Gupta, S.; Tejavath, K.K. Nano Phytoceuticals: A Step Forward in Tracking Down Paths for Therapy Against Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. J. Clust. Sci. 2022, 1–21.

- Dubey, A.K.; Chaudhry, S.K.; Singh, H.B.; Gupta, V.K.; Kaushik, A. Perspectives on Nano-Nutraceuticals to Manage Pre and Post COVID-19 Infections. Biotechnol. Rep. 2022, 33, e00712.

- Shende, P.; Mallick, C. Nanonutraceuticals: A Way towards Modern Therapeutics in Healthcare. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 58, 101838.

- Rambaran, T.F. A Patent Review of Polyphenol Nano-Formulations and Their Commercialization. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 120, 111–122.

- Palla, C.A.; Aguilera-Garrido, A.; Carrín, M.E.; Galisteo-González, F.; Gálvez-Ruiz, M.J. Preparation of Highly Stable Oleogel-Based Nanoemulsions for Encapsulation and Controlled Release of Curcumin. Food Chem. 2022, 378, 132132.

- Harakeh, S.; Qari, Y.; Tashkandi, H.; Almuhayawi, M.; Saber, S.H.; aljahdali, E.; El-Shitany, N.; Shaker, S.; Lucas, F.; Alamri, T.; et al. Thymoquinone Nanoparticles Protect against Cisplatin-Induced Nephrotoxicity in Ehrlich Carcinoma Model without Compromising Cisplatin Anti-Cancer Efficacy. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2022, 34, 101675.

- Radwan, M.F.; El-Moselhy, M.A.; Alarif, W.M.; Orif, M.; Alruwaili, N.K.; Alhakamy, N.A. Optimization of Thymoquinone-Loaded Self-Nanoemulsion for Management of Indomethacin-Induced Ulcer. Dose-Response 2021, 19, 155932582110136.

- Alhakamy, N.A.; Badr-Eldin, S.M.; Ahmed, O.A.A.; Aldawsari, H.M.; Okbazghi, S.Z.; Alfaleh, M.A.; Abdulaal, W.H.; Neamatallah, T.; Al-hejaili, O.D.; Fahmy, U.A. Green Nanoemulsion Stabilized by In Situ Self-Assembled Natural Oil/Native Cyclodextrin Complexes: An Eco-Friendly Approach for Enhancing Anticancer Activity of Costunolide against Lung Cancer Cells. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 227.

- Rinaldi, F.; Maurizi, L.; Forte, J.; Marazzato, M.; Hanieh, P.; Conte, A.; Ammendolia, M.; Marianecci, C.; Carafa, M.; Longhi, C. Resveratrol-Loaded Nanoemulsions: In Vitro Activity on Human T24 Bladder Cancer Cells. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1569.

- Javed Iqbal, M.; Quispe, C.; Javed, Z.; Sadia, H.; Qadri, Q.R.; Raza, S.; Salehi, B.; Cruz-Martins, N.; Abdulwanis Mohamed, Z.; Sani Jaafaru, M.; et al. Nanotechnology-Based Strategies for Berberine Delivery System in Cancer Treatment: Pulling Strings to Keep Berberine in Power. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 7, 624494.

- Cristiano, M.C.; Froiio, F.; Mancuso, A.; Cosco, D.; Dini, L.; Di Marzio, L.; Fresta, M.; Paolino, D. Oleuropein-Laded Ufasomes Improve the Nutraceutical Efficacy. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 105.

- Landucci, E.; Bonomolo, F.; De Stefani, C.; Mazzantini, C.; Pellegrini-Giampietro, D.E.; Bilia, A.R.; Bergonzi, M.C. Preparation of Liposomal Formulations for Ocular Delivery of Thymoquinone: In Vitro Evaluation in HCEC-2 e HConEC Cells. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 2093.

- Rachamalla, H.K.; Bhattacharya, S.; Ahmad, A.; Sridharan, K.; Madamsetty, V.S.; Mondal, S.K.; Wang, E.; Dutta, S.K.; Jan, B.L.; Jinka, S.; et al. Enriched Pharmacokinetic Behavior and Antitumor Efficacy of Thymoquinone by Liposomal Delivery. Nanomedicine 2021, 16, 641–656.

- Castangia, I.; Manconi, M.; Allaw, M.; Perra, M.; Orrù, G.; Fais, S.; Scano, A.; Escribano-Ferrer, E.; Ghavam, M.; Rezvani, M.; et al. Mouthwash Formulation Co-Delivering Quercetin and Mint Oil in Liposomes Improved with Glycol and Ethanol and Tailored for Protecting and Tackling Oral Cavity. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 367.

- Ghorbani, S.; Maryam, A. Encapsulation of Lactic Acid Bacteria and Bifidobacteria Using Starch-sodium Alginate Nanofibers to Enhance Viability in Food Model. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2021, 45, e16048.

- Atraki, R.; Azizkhani, M. Survival of Probiotic Bacteria Nanoencapsulated within Biopolymers in a Simulated Gastrointestinal Model. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2021, 72, 102750.

- Pugliese, R.; Bartolomei, M.; Bollati, C.; Boschin, G.; Arnoldi, A.; Lammi, C. Gel-Forming of Self-Assembling Peptides Functionalized with Food Bioactive Motifs Modulate DPP-IV and ACE Inhibitory Activity in Human Intestinal Caco-2 Cells. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 330.

- Pugliese, R.; Arnoldi, A.; Lammi, C. Nanostructure, Self-Assembly, Mechanical Properties, and Antioxidant Activity of a Lupin-Derived Peptide Hydrogel. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 294.

- Faruk, E.M.; Fouad, H.; Hasan, R.A.A.; Taha, N.M.; El-Shazly, A.M. Inhibition of Gene Expression and Production of INOS and TNF-α in Experimental Model of Neurodegenerative Disorders Stimulated Microglia by Soy Nano-Isoflavone/Stem Cell-Exosomes. Tissue Cell 2022, 76, 101758.