Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Peter Tang and Version 1 by Diplina Paul.

Water contamination due to various nitrogenous pollutants generated from wastewater treatment plants is a crucial and ubiquitous environmental problem nowadays. Nitrogen contaminated water has manifold detrimental effects on human health as well as aquatic life. Consequently, various biological and bioelectrochemical treatment processes are employed to transform the undesirable forms of nitrogen in wastewater to safer ones for subsequent discharge.

- nitrification

- denitrification

- annamox

- microbial fuel cells

- bioelectrochemical processes

- CANON

- SHARON

- OLAND

1. Introduction

The drastic increase in world population has led to intense industrialization and subsequent generation of wastewater from various sources. The generated wastewater is highly nutrient-rich in terms of ammonia, nitrate, nitrite, and other pollutants which need treatment before being discharged. Unless adequately treated, the nitrogenous pollutants from the wastewater can lead to eutrophication, cause methemoglobinemia or blue-baby syndrome, lead to oxygen depletion, aquatic toxicity, and have many other detrimental impacts on the environment [1,2,3,4][1][2][3][4]. Also, the aquaculture industry with intensive aquaculture practices further adds to the generation of wastewater saturated with nitrogenous contaminants [5,6][5][6]. The removal of these nitrogenous entities from wastewater can be conducted by various biological and physicochemical methods. However, the biological processes are more efficient and relatively cost-effective and hence globally adopted and preferred [7,8][7][8]. The biological methods of pollutant removal are generally employed for wastewater with low nitrogen concentration, with nitrification and denitrification being the most conventionally used ones. However, other processes of partial or combined nitrification/denitrification can also be used for nitrogenous removal [9,10,11,12][9][10][11][12].

In addition to this, energy is the most critical challenge that humanity of this century is facing. The challenges in the domain of energy scarcity have been explored by many studies worldwide [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21]. These two challenges of nitrogenous contaminant removal and energy paucity can be simultaneously addressed by bioelectrochemical methods of wastewater treatment [22,23][22][23]. These novel methods also consider that “misplaced resources” is the befitting epithet that can be attributed to waste.

The carbon requirements of nearly all nitrifiers are met by CO2 fixation of the Calvin cycle, and their only source of energy is generated during the oxidation of ammonia [31]. As reported by researchers, 80% of this produced energy is consumed for CO2 fixation, and for each fixed carbon atom, nitrifiers need to oxidize approximately 35 molecules of NH3 or 100 molecules of NO2− [32,33][32][33]. Due to this sluggish growth rate of nitrifiers, their microbial colonization can take 4–8 weeks depending on external parameters such as water temperature, alkalinity, salinity, and other stresses [34,35][34][35].

Parallel as well as in contrast to the other wastewater treatment technologies used, nitrification comes with its own set of advantages and disadvantages. Cost-effectiveness of the process has trade-off in the form of the slow rate of reaction, the requirement of controlling oxygen concentration and the impact of other parameters on nitrification activity, and long hydraulic retention time (HRT) and long solids retention time (SRT). To diminish the energy input of this process, many studies [30,36,37][30][36][37] are being conducted in the domain of partial nitrification, which has an upper hand over conventional nitrification processes in the form of: (i) 40% reduction in chemical oxygen demand (COD); (ii) twice the rate of nitrite reduction in the following denitrification process; (iii) 300% reduction in biomass; and (iv) 20% CO2 emission in the subsequent denitrification process. These studies also report that the partial nitrification process favors the growth and activity of AOB at the cost of inhibiting NOB (with the help of inhibitors like sulfide, hydroxylamine, salt, chlorate, hydrazine, etc. [38]. This is accomplished with consequent positive impacts of parameters like: (i) concentration of dissolved oxygen of about 1.5 mg/L (DO) [39]; (ii) temperature higher than 25 °C [40]; (iii) optimum pH range of 7.5 to 8.5 [36]; and (iv) optimum sludge retention time of 5 days (SRT) [41].

The carbon requirements of nearly all nitrifiers are met by CO2 fixation of the Calvin cycle, and their only source of energy is generated during the oxidation of ammonia [31]. As reported by researchers, 80% of this produced energy is consumed for CO2 fixation, and for each fixed carbon atom, nitrifiers need to oxidize approximately 35 molecules of NH3 or 100 molecules of NO2− [32,33][32][33]. Due to this sluggish growth rate of nitrifiers, their microbial colonization can take 4–8 weeks depending on external parameters such as water temperature, alkalinity, salinity, and other stresses [34,35][34][35].

Parallel as well as in contrast to the other wastewater treatment technologies used, nitrification comes with its own set of advantages and disadvantages. Cost-effectiveness of the process has trade-off in the form of the slow rate of reaction, the requirement of controlling oxygen concentration and the impact of other parameters on nitrification activity, and long hydraulic retention time (HRT) and long solids retention time (SRT). To diminish the energy input of this process, many studies [30,36,37][30][36][37] are being conducted in the domain of partial nitrification, which has an upper hand over conventional nitrification processes in the form of: (i) 40% reduction in chemical oxygen demand (COD); (ii) twice the rate of nitrite reduction in the following denitrification process; (iii) 300% reduction in biomass; and (iv) 20% CO2 emission in the subsequent denitrification process. These studies also report that the partial nitrification process favors the growth and activity of AOB at the cost of inhibiting NOB (with the help of inhibitors like sulfide, hydroxylamine, salt, chlorate, hydrazine, etc. [38]. This is accomplished with consequent positive impacts of parameters like: (i) concentration of dissolved oxygen of about 1.5 mg/L (DO) [39]; (ii) temperature higher than 25 °C [40]; (iii) optimum pH range of 7.5 to 8.5 [36]; and (iv) optimum sludge retention time of 5 days (SRT) [41].

where CH2O represents an organic compound (carbon and energy source) and the denitrifiers use up nitrate instead of oxygen as electron acceptors. Denitrification often needs a posttreatment process, as the various external carbon sources often lead to turbidity (due to the presence of excessive biomass) in the treated water. Additionally, there is always a chance of the generation of the greenhouse gas nitrous oxide, which needs to be monitored [63][46].

where CH2O represents an organic compound (carbon and energy source) and the denitrifiers use up nitrate instead of oxygen as electron acceptors. Denitrification often needs a posttreatment process, as the various external carbon sources often lead to turbidity (due to the presence of excessive biomass) in the treated water. Additionally, there is always a chance of the generation of the greenhouse gas nitrous oxide, which needs to be monitored [63][46].

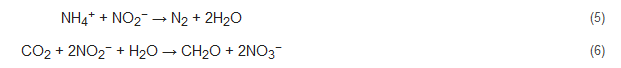

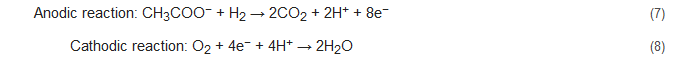

For MFC-

For MFC-

For MEC-

For MEC-

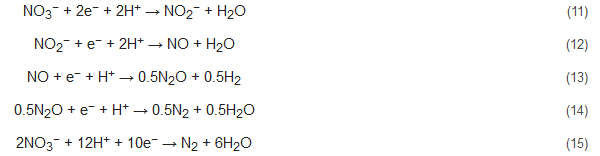

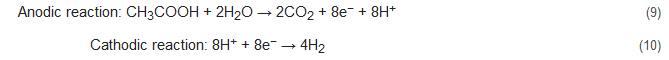

Denitrification by bioelectrochemical systems can be performed in the cathodic chamber of the cells. Here, EAB in the anode oxidizes the substrate (like acetate) and supplies electrons which are utilized by the EAB at the cathode to perform denitrification. A tubular reactor MFC designed by Clauwaert et al. used acetate as an electron donor to perform denitrification with simultaneous bioelectricity production. The stepwise nitrate reduction reactions in this denitrification process are as follows [85][50]:

Denitrification by bioelectrochemical systems can be performed in the cathodic chamber of the cells. Here, EAB in the anode oxidizes the substrate (like acetate) and supplies electrons which are utilized by the EAB at the cathode to perform denitrification. A tubular reactor MFC designed by Clauwaert et al. used acetate as an electron donor to perform denitrification with simultaneous bioelectricity production. The stepwise nitrate reduction reactions in this denitrification process are as follows [85][50]:

Zhao et al. had studied the performance of denitrifying MFCs with nitrite as an electron acceptor in the cathode with successful nitrite and total nitrogen removal [86][51]. They had also observed the predominance of the phylum Proteobacteria (35.72%) along with Thiobacillus, Afipia, and Devosia. Additionally, Zhu et al. and Zekker et al. had reported the occurrence of simultaneous nitrification-denitrification and anammox-denitrification, respectively, in MFCs to enhance the removal of nitrogenous contaminants from wastewater with concomitant and enhanced bioelectricity recovery [87,88][52][53]. Nitrogen removal by bioelectrochemical systems offers various benefits like diminished environmental impact, ability to remove specific pollutants, relatively inexpensive operating factors etc.

Zhao et al. had studied the performance of denitrifying MFCs with nitrite as an electron acceptor in the cathode with successful nitrite and total nitrogen removal [86][51]. They had also observed the predominance of the phylum Proteobacteria (35.72%) along with Thiobacillus, Afipia, and Devosia. Additionally, Zhu et al. and Zekker et al. had reported the occurrence of simultaneous nitrification-denitrification and anammox-denitrification, respectively, in MFCs to enhance the removal of nitrogenous contaminants from wastewater with concomitant and enhanced bioelectricity recovery [87,88][52][53]. Nitrogen removal by bioelectrochemical systems offers various benefits like diminished environmental impact, ability to remove specific pollutants, relatively inexpensive operating factors etc.

Reactions with NOx supply:

Reactions with NOx supply:

2. Conventional Biological Treatment Processes

2.1. Nitrification

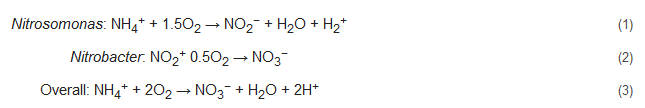

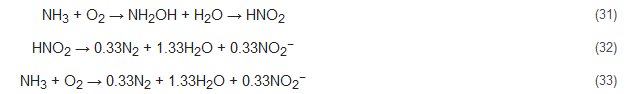

Nitrification includes two successive biological oxidation steps: (1) oxidation of NH4+ to NO2− and (2) conversion of NO2− to NO3−. The first step is carried out by ammonium oxidizing bacteria (AOB, e.g., Nitrosomonas) with catalyzation by ammonia monooxygenase (AMO) [24,25,26,27][24][25][26][27] and hydroxylamine oxidoreductase (HAO) [28,29][28][29], along with the formation of the intermediate product hydroxylamine (NH2OH). The second step of nitrification, which entails the formation of NO3−, is carried out by nitrite-oxidizing bacteria (NOB, e.g., Nitrobacter) in the presence of molecular oxygen. Catalyzation of this step is performed by nitrite oxidoreductases (NXR) and nitrite-oxidizing systems. NXR is an oxidation enzyme that occurs in Nitrobacter [30]. The reaction pathway of this process can be represented by: Nitrosomonas: The carbon requirements of nearly all nitrifiers are met by CO2 fixation of the Calvin cycle, and their only source of energy is generated during the oxidation of ammonia [31]. As reported by researchers, 80% of this produced energy is consumed for CO2 fixation, and for each fixed carbon atom, nitrifiers need to oxidize approximately 35 molecules of NH3 or 100 molecules of NO2− [32,33][32][33]. Due to this sluggish growth rate of nitrifiers, their microbial colonization can take 4–8 weeks depending on external parameters such as water temperature, alkalinity, salinity, and other stresses [34,35][34][35].

Parallel as well as in contrast to the other wastewater treatment technologies used, nitrification comes with its own set of advantages and disadvantages. Cost-effectiveness of the process has trade-off in the form of the slow rate of reaction, the requirement of controlling oxygen concentration and the impact of other parameters on nitrification activity, and long hydraulic retention time (HRT) and long solids retention time (SRT). To diminish the energy input of this process, many studies [30,36,37][30][36][37] are being conducted in the domain of partial nitrification, which has an upper hand over conventional nitrification processes in the form of: (i) 40% reduction in chemical oxygen demand (COD); (ii) twice the rate of nitrite reduction in the following denitrification process; (iii) 300% reduction in biomass; and (iv) 20% CO2 emission in the subsequent denitrification process. These studies also report that the partial nitrification process favors the growth and activity of AOB at the cost of inhibiting NOB (with the help of inhibitors like sulfide, hydroxylamine, salt, chlorate, hydrazine, etc. [38]. This is accomplished with consequent positive impacts of parameters like: (i) concentration of dissolved oxygen of about 1.5 mg/L (DO) [39]; (ii) temperature higher than 25 °C [40]; (iii) optimum pH range of 7.5 to 8.5 [36]; and (iv) optimum sludge retention time of 5 days (SRT) [41].

The carbon requirements of nearly all nitrifiers are met by CO2 fixation of the Calvin cycle, and their only source of energy is generated during the oxidation of ammonia [31]. As reported by researchers, 80% of this produced energy is consumed for CO2 fixation, and for each fixed carbon atom, nitrifiers need to oxidize approximately 35 molecules of NH3 or 100 molecules of NO2− [32,33][32][33]. Due to this sluggish growth rate of nitrifiers, their microbial colonization can take 4–8 weeks depending on external parameters such as water temperature, alkalinity, salinity, and other stresses [34,35][34][35].

Parallel as well as in contrast to the other wastewater treatment technologies used, nitrification comes with its own set of advantages and disadvantages. Cost-effectiveness of the process has trade-off in the form of the slow rate of reaction, the requirement of controlling oxygen concentration and the impact of other parameters on nitrification activity, and long hydraulic retention time (HRT) and long solids retention time (SRT). To diminish the energy input of this process, many studies [30,36,37][30][36][37] are being conducted in the domain of partial nitrification, which has an upper hand over conventional nitrification processes in the form of: (i) 40% reduction in chemical oxygen demand (COD); (ii) twice the rate of nitrite reduction in the following denitrification process; (iii) 300% reduction in biomass; and (iv) 20% CO2 emission in the subsequent denitrification process. These studies also report that the partial nitrification process favors the growth and activity of AOB at the cost of inhibiting NOB (with the help of inhibitors like sulfide, hydroxylamine, salt, chlorate, hydrazine, etc. [38]. This is accomplished with consequent positive impacts of parameters like: (i) concentration of dissolved oxygen of about 1.5 mg/L (DO) [39]; (ii) temperature higher than 25 °C [40]; (iii) optimum pH range of 7.5 to 8.5 [36]; and (iv) optimum sludge retention time of 5 days (SRT) [41].

2.2. Denitrification

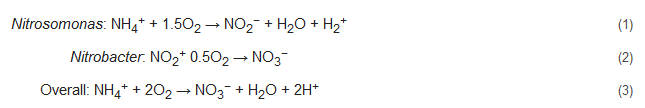

Denitrification is the process whereby nitrate is converted to nitrogen gas as the end product. It is generally the subsequent step of nitrification and is mostly performed by heterotrophic denitrifiers but can also be carried out by a limited number of autotrophic nitrifiers [5,59][5][42]. Various parameters play a major role in this process viz. maintenance of anoxic conditions, supply of carbon source, and subsequent treatment of the treated wastewater. The use of an external organic source of carbon is needed as external carbon can act as an electron donor needed for the growth of denitrifiers. The external sources of carbon include glucose, methanol, ethanol, succinate, and acetate [60,61][43][44]. The denitrification process of converting nitrate to nitrogen gas follows the following reaction [62][45]: where CH2O represents an organic compound (carbon and energy source) and the denitrifiers use up nitrate instead of oxygen as electron acceptors. Denitrification often needs a posttreatment process, as the various external carbon sources often lead to turbidity (due to the presence of excessive biomass) in the treated water. Additionally, there is always a chance of the generation of the greenhouse gas nitrous oxide, which needs to be monitored [63][46].

where CH2O represents an organic compound (carbon and energy source) and the denitrifiers use up nitrate instead of oxygen as electron acceptors. Denitrification often needs a posttreatment process, as the various external carbon sources often lead to turbidity (due to the presence of excessive biomass) in the treated water. Additionally, there is always a chance of the generation of the greenhouse gas nitrous oxide, which needs to be monitored [63][46].

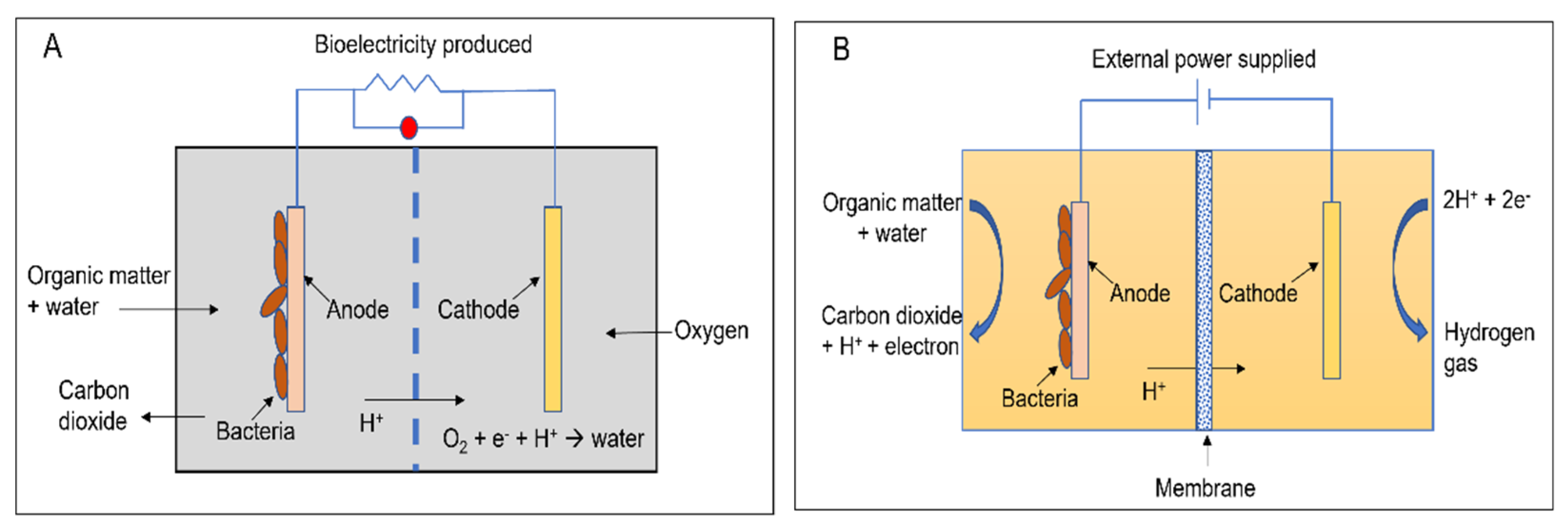

2.3. Anammox

Anammox or anaerobic ammonium oxidation is a recently studied energy-efficient nitrogen removal process that is gaining popularity. In this process, nitrite and ammonium are used up, resulting in the formation of nitrogen gas along with NO and N2H4 intermediates (Equation (5)). In other words, it is the denitrification of nitrite, with ammonia acting as an electron donor. The nitrite can be gained from the oxidation of ammonium (nitrification) as well as partial denitrification of nitrate. Additionally, the anammox bacteria metabolize by using CO2 as their only source of carbon and nitrite as an electron donor (Equation (6)) [7]. The nitrification/denitrification can consume up to 100% of the organic content of the wastewater. Nitrification/anammox can produce methane gas which can aid in bioenergy recovery from wastewater treatment [72][47]. The first full-fledged anammox reactor was established for the treatment of reject water in Rotterdam, Netherlands, and has ever since gained wide popularity and application [30].

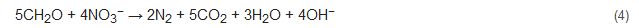

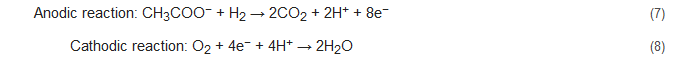

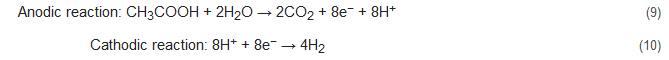

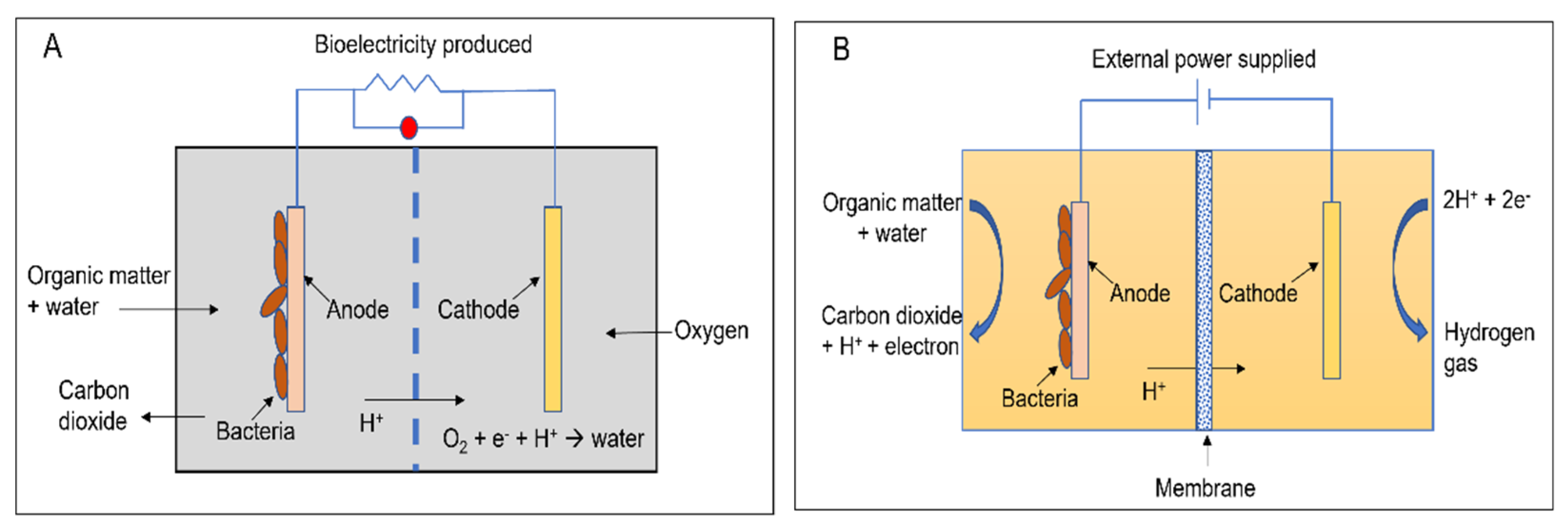

3. Bioelectrochemical Systems

Apart from the conventional biological methods of nitrogen removal from wastewater, there is an increased interest currently in the various innovative bioelectrochemical alternatives. Such systems directly convert chemical energy present in the chemical bonds of the organic matter into electricity via electrochemically active bacteria (EAB), e.g., electricigens, and have potential applications for simultaneous nitrogen and other contaminants removal from wastewater with bioenergy recovery [22,23][22][23]. Here, the electrons are shifted to the anode after the oxidation of the pollutants, thereby removing them due to organic matter decomposition. Bioelectrochemical systems can be of two major types, conditional on the cathodic reaction: microbial fuel cells (MFCs; Figure 1A) and microbial electrolysis cells (MECs; Figure 1B). The former generates electrical power as the anodic oxidation works in tandem with cathodic reduction where electron acceptors with high reduction potential get reduced. The latter needs an externally supplied voltage (>0.2 V) under a biologically conducive environment, where EAB oxidizes the organic matter to produce CO2, electrons, and protons. Subsequently, the EAB transfer the electrons to the anode and release the protons to the wastewater getting treated. When acetate is used as a substrate, the electrode reactions occurring are as follows [83,84][48][49]:

Figure 1.

A two-chambered (

A

) microbial fuel cell and (

B

) microbial electrolysis cell.

For MEC-

For MEC-

Denitrification by bioelectrochemical systems can be performed in the cathodic chamber of the cells. Here, EAB in the anode oxidizes the substrate (like acetate) and supplies electrons which are utilized by the EAB at the cathode to perform denitrification. A tubular reactor MFC designed by Clauwaert et al. used acetate as an electron donor to perform denitrification with simultaneous bioelectricity production. The stepwise nitrate reduction reactions in this denitrification process are as follows [85][50]:

Denitrification by bioelectrochemical systems can be performed in the cathodic chamber of the cells. Here, EAB in the anode oxidizes the substrate (like acetate) and supplies electrons which are utilized by the EAB at the cathode to perform denitrification. A tubular reactor MFC designed by Clauwaert et al. used acetate as an electron donor to perform denitrification with simultaneous bioelectricity production. The stepwise nitrate reduction reactions in this denitrification process are as follows [85][50]:

Zhao et al. had studied the performance of denitrifying MFCs with nitrite as an electron acceptor in the cathode with successful nitrite and total nitrogen removal [86][51]. They had also observed the predominance of the phylum Proteobacteria (35.72%) along with Thiobacillus, Afipia, and Devosia. Additionally, Zhu et al. and Zekker et al. had reported the occurrence of simultaneous nitrification-denitrification and anammox-denitrification, respectively, in MFCs to enhance the removal of nitrogenous contaminants from wastewater with concomitant and enhanced bioelectricity recovery [87,88][52][53]. Nitrogen removal by bioelectrochemical systems offers various benefits like diminished environmental impact, ability to remove specific pollutants, relatively inexpensive operating factors etc.

Zhao et al. had studied the performance of denitrifying MFCs with nitrite as an electron acceptor in the cathode with successful nitrite and total nitrogen removal [86][51]. They had also observed the predominance of the phylum Proteobacteria (35.72%) along with Thiobacillus, Afipia, and Devosia. Additionally, Zhu et al. and Zekker et al. had reported the occurrence of simultaneous nitrification-denitrification and anammox-denitrification, respectively, in MFCs to enhance the removal of nitrogenous contaminants from wastewater with concomitant and enhanced bioelectricity recovery [87,88][52][53]. Nitrogen removal by bioelectrochemical systems offers various benefits like diminished environmental impact, ability to remove specific pollutants, relatively inexpensive operating factors etc.

4. Other Treatment Processes for Nitrogen Removal

Apart from the conventional biological and the novel bioelectrochemical processes discussed above, researchers are now studying other innovative microbial potentials as well. This has become possible due to the ushering of new findings that the conversion of ammonium from wastewater to dinitrogen gas does not demand the absolute oxidation to nitrate that is consequently succeeded by heterotrophic denitrification. The following are a few such processes that explore the microbial abilities of the bacterial communities that can occur even during incomplete/partial oxidation of ammonium to nitrogen gas.4.1. NO

x

Process

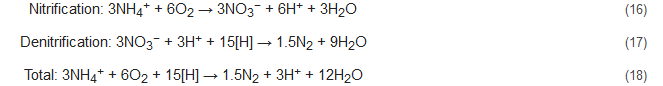

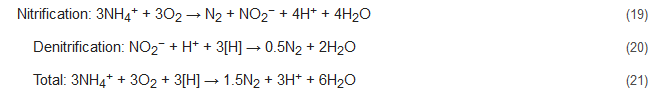

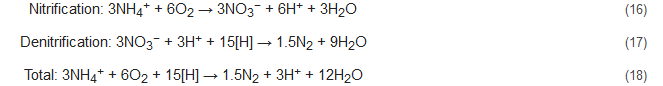

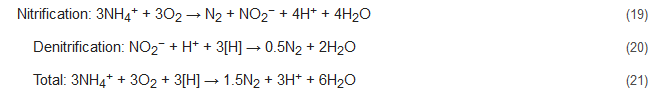

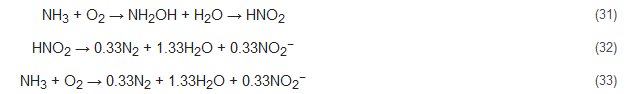

During the NOx process, the denitrification activity of bacteria similar to Nitrosomonas is controlled and stimulated by the addition of trace amounts of nitrogen oxides. The ratios of ammonium to nitrogen oxide that are added range from 1000:1 to 5000:1 [89,90][54][55]. With NOx supply under completely oxic conditions, the Nitrosomonas-like bacteria can nitrify as well as denitrify concomitantly, with N2 being the primary product. This process brings about 40% conversion of the ammonia present to nitrite and decreases the oxygen demand during the nitrification process by 50% with succeeding denitrification consuming less COD [7]. This is because here nitrite acts as the terminal electron acceptor to complete the process. The integrated nitrification-denitrification steps without NOx supply are represented below by Equations (16)–(18) and that with NOx supply by Equations (19)–(21). Here, the [H] denotes the reducing equivalents as provided by the external C-source. However, the stoichiometry and results might be influenced by the composition of the wastewater studied [91][56]. Conventional reactions: Reactions with NOx supply:

Reactions with NOx supply:

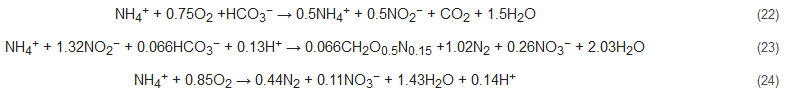

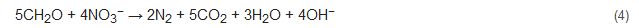

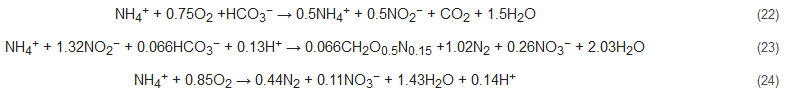

4.2. Completely Autotrophic Nitrogen Removal over Nitrite (CANON)

The CANON process is an integration of partial nitrification and anammox processes [92,93,94][57][58][59]. The name of this process derives from the sequential working mechanism of the two sets of bacterial communities in a single and aerated reactor: Nitrosomonas-like aerobic and Planctomycete-like anaerobic bacteria (Equations (22) to (24)). These bacteria work in tandem to oxidize ammonia to nitrite (by nitrifiers), thereby consuming oxygen and subsequently creating an anoxic environment for anammox to proceed. This process is relatively sensitive to operational parameters viz. dissolved oxygen, the thickness of the biofilm developed, temperature, and loading rates of nitrogen [95][60]. This process has the economic advantage of requiring only a single reactor for operation.

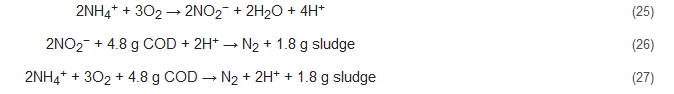

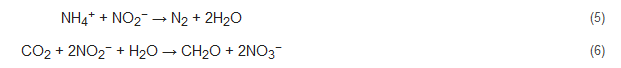

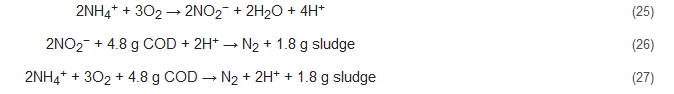

4.3. Single-Reactor High-Activity Ammonium Removal over Nitrite (SHARON)

The SHARON process is a type of partial nitrification process that was initially conceptualized for ammonia removal by the nitrite path [96,97][61][62]. Here, both autotrophic nitrification and heterotrophic denitrification occur simultaneously in one SHARON reactor with sporadic aeration. This process is however not conducive for all types of wastewaters as it requires high temperature and works well for the elimination of high ammonium concentration (>0.5 g/L). Additionally, methanol needs to be added during the denitrification step of this process to better regulate pH and alkalinity production, required to balance the acidifying consequence of nitrification step. Equations (25)–(27) represent the stoichiometry of this process [7]:

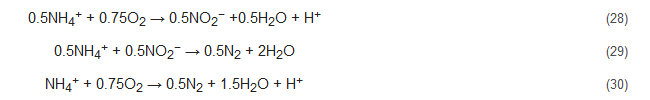

4.4. Oxygen-Limited Autotrophic Nitrification and Denitrification (OLAND)

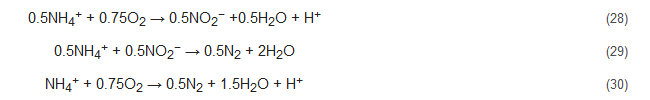

The OLAND process has been upheld by researchers as a one-step removal of ammonium without any supply of COD [98][63]. Though it is widely accepted that Nitrifiers are the responsible microorganisms in this process, nonetheless, studies are still being conducted to completely comprehend the mechanisms involved. Nevertheless, it appears to be based on either the CANON concept or the NOx process, i.e., the functioning of aerobic and anaerobic ammonia oxidizers or that of nitrifying denitrifiers with NOx being available [91][56]. Here, both the conversion efficiency and nitrogen loading rates are quite stunted [31,99][31][64]. The OLAND process has been represented by the following reactions [7]:

4.5. Aerobic Deammonification

Aerobic deammonification is yet another single-step process of ammonium removal that is independent of COD supply. In this process, a part of the ammonium is converted to dinitrogen gas and another part to nitrate [91,100][56][65]. This process majorly works on the concept of CANON mechanism, where nitrifiers and anaerobic ammonia oxidizers collaborate under limited oxygen supply. However, the nitrogen loading, as well as removal rates, are stunted here. The following reactions illustrate the aerobic deammonification process:

References

- Xu, W.; Xu, Y.; Su, H.; Hu, X.; Yang, K.; Wen, G.; Cao, Y. Characteristics of Ammonia Removal and Nitrifying Microbial Communities in a Hybrid Biofloc-RAS for Intensive Litopenaeus vannamei Culture: A Pilot-Scale Study. Water 2020, 12, 3000.

- Cheng, X.; Zhu, D.; Wang, X.; Yu, D.; Xie, J. Effects of Nonaerated Circulation Water Velocity on Nutrient Release from Aquaculture Pond Sediments. Water 2016, 9, 6.

- Humphrey, C.; O’Driscoll, M.; Iverson, G. Comparison of Nitrogen Treatment by Four Onsite Wastewater Systems in Nutrient-Sensitive Watersheds of the North Carolina Coastal Plain. Nitrogen 2021, 2, 268–286.

- Yousaf, A.; Khalid, N.; Aqeel, M.; Noman, A.; Naeem, N.; Sarfraz, W.; Ejaz, U.; Qaiser, Z.; Khalid, A. Nitrogen Dynamics in Wetland Systems and Its Impact on Biodiversity. Nitrogen 2021, 2, 196–217.

- Paul, D. Biological and Adsorptive Removal of Nitrogenous Species from Aquaculture Wastewater. Ph.D. Thesie, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC, USA, May 2021. Available online: https://www.lib.ncsu.edu/resolver/1840.20/39013 (accessed on 12 May 2022).

- Hall, S.G.; Campbell, M.; Geddie, A.; Thomas, M.; Paul, D.; Wilcox, D.; Smith, R.; Eddy, N.; Frinsko, M.; Wilder, S.; et al. Engineering challenges in marine aquaculture. In Proceedings of the 2018 ASABE Annual International Meeting, Detroit, MI, USA, 29 July–1 August 2018; American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers: St. Joseph, MI, USA, 2018.

- Ahn, Y.-H. Sustainable nitrogen elimination biotechnologies: A review. Process Biochem. 2006, 41, 1709–1721.

- EPA US. Process Design Manual of Nitrogen Control 1993. Available online: https://cfpub.epa.gov/si/si_public_record_Report.cfm?Lab=NRMRL&dirEntryID=34313 (accessed on 31 March 2022).

- Ali, M.; Okabe, S. Anammox-based technologies for nitrogen removal: Advances in process start-up and remaining issues. Chemosphere 2015, 141, 144–153.

- Arredondo, M.R.; Kuntke, P.; Jeremiasse, A.W.; Sleutels, T.H.J.A.; Buisman, C.J.N.; Ter Heijne, A. Bioelectrochemical systems for nitrogen removal and recovery from wastewater. Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol. 2015, 1, 22–33.

- Taziki, M.; Ahmadzadeh, H.; Murry, M.A.; Lyon, S.R. Nitrate and Nitrite Removal from Wastewater using Algae. Curr. Biotechnol. 2016, 4, 426–440.

- Gonçalves, A.L.; Pires, J.C.M.; Simões, M. A review on the use of microalgal consortia for wastewater treatment. Algal Res. 2017, 24, 403–415.

- Banerjee, A.; Paul, D. Developments and applications of porous medium combustion: A recent review. Energy 2021, 221, 119868.

- Banerjee, A.; Roy, S.; Mukherjee, P.; Saha, U.K. Unsteady flow analysis around an elliptic-bladed Savonius-style wind turbine. In Proceedings of the Gas Turbine India Conference, New Delhi, India, 15–17 December 2014; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Volume 49644, p. V001T05A001.

- Banerjee, A.; Saveliev, A.V. High temperature heat extraction from counterflow porous burner. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 127, 436–443.

- Banerjee, A. Performance and flow analysis of an elliptic bladed Savonius-style wind turbine. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2019, 11, 033307.

- Banerjee, A.; Kundu, P.; Gnatenko, V.; Zelepouga, S.; Wagner, J.; Chudnovsky, Y.; Saveliev, A. NOx Minimization in Staged Combustion Using Rich Premixed Flame in Porous Media. Combust. Sci. Technol. 2020, 192, 1633–1649.

- Banerjee, A.; Saveliev, A. Emission characteristics of heat recirculating porous burners with high temperature energy extraction. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 67.

- Paul, D.; Banerjee, A. Genetic algorithm based optimization technique for Savonius-style wind turbine. In Proceedings of the Gas Turbine India Conference, Virtual, Online, 2–3 December 2021; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Volume 76041, p. V001T09A009.

- Paul, D.; Banerjee, A. Efficiency analysis of Savonius-style wind turbine in hydrodynamic flow field. In Proceedings of the Gas Turbine India Conference, Virtual, Online, 2–3 December 2021; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Volume 76209, p. V001T09A010.

- Paul, D.; Banerjee, A. Experimental investigation of performance characteristics for Savonius-style VAWTs: A comparative study. In Proceedings of the Gas Turbine India Conference, Virtual, Online, 2–3 December 2021; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Volume 76040, p. V001T09A008.

- Paul, D.; Noori, T.; Rajesh, P.; Ghangrekar, M.; Mitra, A. Modification of carbon felt anode with graphene oxide-zeolite composite for enhancing the performance of microbial fuel cell. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2018, 26, 77–82.

- Noori, T.; Paul, D.; Ghangrekar, M.M.; Mukherjee, C.K. Enhancing the Performance of Sediment Microbial Fuel Cell using Graphene Oxide–Zeolite Modified Anode and V2O5 Catalyzed Cathode. J. Clean Energy Technol. 2018, 6(2), 150–154.

- Caranto, J.D.; Lancaster, K.M. Nitric oxide is an obligate bacterial nitrification intermediate produced by hydroxylamine oxidoreductase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 8217–8222.

- Daims, H.; Lücker, S.; Wagner, M. A New Perspective on Microbes Formerly Known as Nitrite-Oxidizing Bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 2016, 24, 699–712.

- Sedlacek, C.J.; Nielsen, S.; Greis, K.D.; Haffey, W.D.; Revsbech, N.P.; Ticak, T.; Laanbroek, H.J.; Bollmann, A. Effects of Bacterial Community Members on the Proteome of the Ammonia-Oxidizing Bacterium Nitrosomonas sp. Strain Is79. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 4776–4788.

- Wang, M.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Wang, C.; Zhu, Y.; Tian, Q. The New Developments Made in the Autotrophic and Heterotrophic Ammonia Oxidation. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 178, 012016.

- Beman, J.M.; Sachdeva, R.; Fuhrman, J. Population ecology of nitrifying Archaea and Bacteria in the Southern California Bight. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 12, 1282–1292.

- Dionisi, H.M.; Layton, A.C.; Harms, G.; Gregory, I.R.; Robinson, K.G.; Sayler, G.S. Quantification of Nitrosomonas oligotropha-like Ammonia-Oxidizing Bacteria and Nitrospira spp. from Full-Scale Wastewater Treatment Plants by Competitive PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 245–253.

- Rahimi, S.; Modin, O.; Mijakovic, I. Technologies for biological removal and recovery of nitrogen from wastewater. Biotechnol. Adv. 2020, 43, 107570.

- Philips, S.; Laanbroek, H.J.; Verstraete, W. Origin, causes and effects of increased nitrite concentrations in aquatic environments. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2002, 1, 115–141.

- Kelly, D.P. Bioenergetics of chemolithotrophic bacteria. Companion Microbiol. 1978, 363–386.

- Wood, P.M. Nitrification as a bacterial energy source. Spec. Publ. Soc. Gen. Microbiol. 1986, 20, 39–67.

- Emparanza, E.J. Problems affecting nitrification in commercial RAS with fixed-bed biofilters for salmonids in Chile. Aquac. Eng. 2009, 41, 91–96.

- Malone, R.F.; Pfeiffer, T.J. Rating fixed film nitrifying biofilters used in recirculating aquaculture systems. Aquac. Eng. 2006, 34, 389–402.

- Ge, S.; Wang, S.; Yang, X.; Qiu, S.; Li, B.; Peng, Y. Detection of nitrifiers and evaluation of partial nitrification for wastewater treatment: A review. Chemosphere 2015, 140, 85–98.

- Cao, Y.; Van Loosdrecht, M.C.M.; Daigger, G.T. Mainstream partial nitritation–anammox in municipal wastewater treatment: Status, bottlenecks, and further studies. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 101, 1365–1383.

- Sinha, B.; Annachhatre, A.P. Partial nitrification—Operational parameters and microorganisms involved. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2007, 6, 285–313.

- Liu, C.; Shi, W.; Li, H.; Lei, Z.; He, L.; Zhang, Z. Improvement of methane production from waste activated sludge by on-site photocatalytic pretreatment in a photocatalytic anaerobic fermenter. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 155, 198–203.

- Paredes, D.; Kuschk, P.; Mbwette, T.S.A.; Stange, C.F.; Müller, R.A.; Köser, H. New Aspects of Microbial Nitrogen Transformations in the Context of Wastewater Treatment—A Review. Eng. Life Sci. 2007, 7, 13–25.

- Galí, A.; Dosta, J.; van Loosdrecht, M.; Mata-Alvarez, J. Two ways to achieve an anammox influent from real reject water treatment at lab-scale: Partial SBR nitrification and SHARON process. Process Biochem. 2007, 42, 715–720.

- Paul, D.; Hall, S.G. Biochar and Zeolite as Alternative Biofilter Media for Denitrification of Aquaculture Effluents. Water 2021, 13, 2703.

- Razak, M.N.A.; Ibrahim, M.F.; Yee, P.L.; Hassan, M.A.; Abd-Aziz, S. Utilization of oil palm decanter cake for cellulase and polyoses production. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 2012, 17, 547–555.

- Miao, L.; Liu, Z. Microbiome analysis and -omics studies of microbial denitrification processes in wastewater treatment: Recent advances. Sci. China Life Sci. 2018, 61, 753–761.

- Delwiche, C.C. Denitrification, nitrification and atmospheric nitrous oxide. In The Nitrogen Cycle and Nitrous Oxide; Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1981.

- Wang, X.M.; Wang, J.L. Nitrate removal from groundwater using solid-phase denitrification process without inoculating with external microorganisms. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 10, 955–960.

- Kartal, B.; Kuenen, J.G.; van Loosdrecht, M.C.M. Sewage Treatment with Anammox. Science 2010, 328, 702–703.

- Kadier, A.; Simayi, Y.; Abdeshahian, P.; Azman, N.F.; Chandrasekhar, K.; Kalil, M.S. A comprehensive review of microbial electrolysis cells (MEC) reactor designs and configurations for sustainable hydrogen gas production. Alex. Eng. J. 2016, 55, 427–443.

- Ucar, D.; Zhang, Y.; Angelidaki, I. An Overview of Electron Acceptors in Microbial Fuel Cells. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 643.

- Clauwaert, P.; Rabaey, K.; Aelterman, P.; De Schamphelaire, L.; Pham, T.H.; Boeckx, P.; Boon, N.; Verstraete, W. Biological Denitrification in Microbial Fuel Cells. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 3354–3360.

- Zhao, H.; Zhao, J.; Li, F.; Li, X. Performance of Denitrifying Microbial Fuel Cell with Biocathode over Nitrite. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 344.

- Zekker, I.; Bhowmick, G.D.; Priks, H.; Nath, D.; Rikmann, E.; Jaagura, M.; Tenno, T.; Tämm, K.; Ghangrekar, M.M. ANAMMOX-denitrification biomass in microbial fuel cell to enhance the electricity generation and nitrogen removal efficiency. Biodegradation 2020, 31, 249–264.

- Zhu, G.; Huang, S.; Lu, Y.; Gu, X. Simultaneous nitrification and denitrification in the bio-cathode of a multi-anode microbial fuel cell. Environ. Technol. 2021, 42, 1260–1270.

- Schmidt, I.; Zart, D.; Bock, E. Gaseous NO2 as a regulator for ammonia oxidation of Nitrosomonas eutropha. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 2001, 79, 311–318.

- Schmidt, I.; Hermelink, C.; van de Pas-Schoonen, K.; Strous, M.; Camp, H.J.O.D.; Kuenen, J.G.; Jetten, M.S.M. Anaerobic Ammonia Oxidation in the Presence of Nitrogen Oxides (NOx) by Two Different Lithotrophs. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 5351–5357.

- Schmidt, I.; Sliekers, O.; Schmid, M.; Bock, E.; Fuerst, J.; Kuenen, J.G.; Jetten, M.S.; Strous, M. New concepts of microbial treatment processes for the nitrogen removal in wastewater. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2003, 27, 481–492.

- Strous, M.; Van Gerven, E.; Kuenen, J.G.; Jetten, M. Effects of aerobic and microaerobic conditions on anaerobic ammonium-oxidizing (anammox) sludge. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997, 63, 2446–2448.

- Koch, G.; Egli, K.; van der Meer, J.R.; Siegrist, H. Mathematical modeling of autotrophic denitrification in a nitrifying biofilm of a rotating biological contactor. Water Sci. Technol. 2000, 41, 191–198.

- Third, K.; Sliekers, A.O.; Kuenen, J.; Jetten, M. The CANON System (Completely Autotrophic Nitrogen-removal over Nitrite) under Ammonium Limitation: Interaction and Competition between Three Groups of Bacteria. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2001, 24, 588–596.

- Van Loosdrecht, M.C.M. Recent development on biological wastewater nitrogen removal technologies. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Wastewater Treatment for Nutrient Removal and Reuse (ICWNR’04), Pathumthani, Thailand, 26–29 January 2004.

- Jetten, M.S.; Schmid, M.; Schmidt, I.; Wubben, M.; Van Dongen, U.; Abma, W.; Sliekers, O.; Revsbech, N.P.; Beaumont, H.J.; Ottosen, L.; et al. Improved nitrogen removal by application of new nitrogen-cycle bacteria. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2002, 1, 51–63.

- Hellinga, C.; Schellen, A.; Mulder, J.; van Loosdrecht, M.; Heijnen, J. The sharon process: An innovative method for nitrogen removal from ammonium-rich waste water. Water Sci. Technol. 1998, 37, 135–142.

- Kuai, L.; Verstraete, W. Ammonium Removal by the Oxygen-Limited Autotrophic Nitrification-Denitrification System. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1998, 64, 4500–4506.

- Pynaert, K.; Smets, B.F.; Wyffels, S.; Beheydt, D.; Siciliano, S.; Verstraete, W. Characterization of an Autotrophic Nitrogen-Removing Biofilm from a Highly Loaded Lab-Scale Rotating Biological Contactor. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 3626–3635.

- Hippen, A.; Helmer, C.; Kunst, S.; Rosenwinkel, K.-H.; Seyfried, C.F. Six years’ practical experience with aerobic/anoxic deammonification in biofilm systems. Water Sci. Technol. 2001, 44, 39–48.

More