The United Nations, in the context of its founding principles and in order to contribute to the preservation of peace and justice in all the countries, confirmed at the Geneva Conferences in 1958 and 1960 that there should be an acceptable convention for the law of the sea. The complete version of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) was presented in 1982 in Montego Bay, Jamaica (https://treaties.un.org/Pages/Treaties.aspx?id=21&subid=0&lang=en&clang=_en (accessed on 8 May 2022)), entered into force in 1994, and is today the world’s most recognized maritime law regime. The central idea of the UNCLOS convention is that maritime problems are interconnected and should be tackled as a whole. The provisions of the UN convention apply to all areas of marine affairs, including the organization and development of productive activities and the emergence of marine entrepreneurship.

- marine spatial planning (MSP)

- marine spatial data infrastructure (MSDI)

- marine cadastre

- United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)

- maritime zones

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP)

- Integrated Maritime Policy

- Blue Growth Strategy

1. International Governance Framework for the Sea

1.1. United Nations Convention for the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)

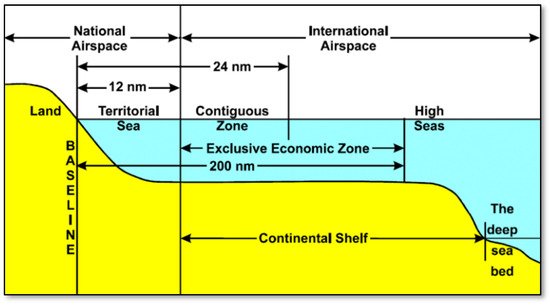

1.2. Sea Zones in Accordance with UNCLOS Provisions

1.3. Delimitation of Maritime Zones

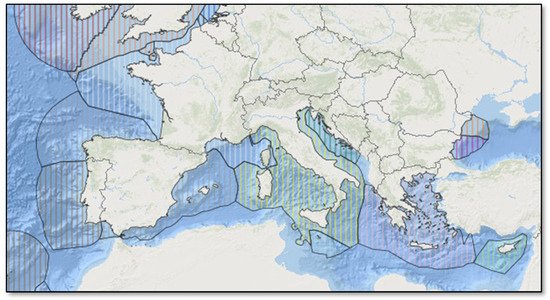

1.4. The UNEP Regional Seas Programme

2. European Governance Framework for the Sea

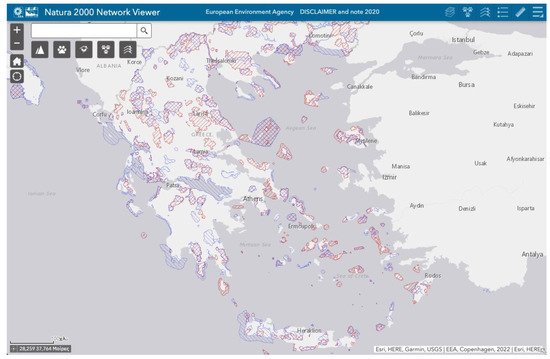

2.1. Directive on the Conservation of Natural Habitats

2.2. Integrated Maritime Policy

2.2.1. Blue Growth Strategy

- (a)

-

Developing the marine sectors with the promise for long-term jobs creation and expansion.

- (b)

-

Providing knowledge, regulatory stability, and confidence in the ocean economy.

- (c)

-

Implementing sea basin policies to ensure states’ collaboration.

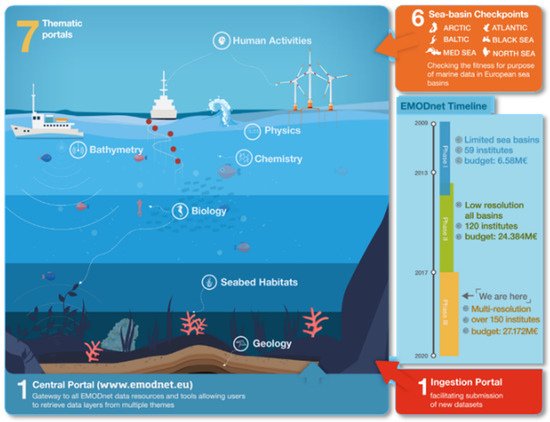

2.2.2. Data and Knowledge about the Sea

- Enhance efficiency in all operations that use marine data by minimizing data recollection and the expenses for gathering.

- Boost competitiveness and creativity in existing and emerging maritime industries.

- Decrease ambiguity in our understanding of the oceans and increase our ability to forecast.

-

Enhance efficiency in all operations that use marine data by minimizing data recollection and the expenses for gathering.

-

Boost competitiveness and creativity in existing and emerging maritime industries.

-

Decrease ambiguity in our understanding of the oceans and increase our ability to forecast.

2.3. Marine Spatial Planning Directive

- The rising interest for marine space for various marine activities, such as energy plants, oil and gas extraction, shipping, fishing, biodiversity conservation, tourism, and underwater cultural heritage, in conjunction with the numerous demands on coastal resources necessitate a holistic approach to planning and management of marine domain.

- Adopting an ecosystem-based approach will aid in the long-term development and expansion of marine and coastal economies and the responsible use of coastal and marine resources.

- To encourage the sustained coexisting of activities and, when applicable, the proper placement of complementary uses in the marine region, a framework is needed that typically includes the acceptance and execution by Member States of marine spatial planning outcomes in appropriate charts.

-

The rising interest for marine space for various marine activities, such as energy plants, oil and gas extraction, shipping, fishing, biodiversity conservation, tourism, and underwater cultural heritage, in conjunction with the numerous demands on coastal resources necessitate a holistic approach to planning and management of marine domain.

-

Adopting an ecosystem-based approach will aid in the long-term development and expansion of marine and coastal economies and the responsible use of coastal and marine resources.

-

To encourage the sustained coexisting of activities and, when applicable, the proper placement of complementary uses in the marine region, a framework is needed that typically includes the acceptance and execution by Member States of marine spatial planning outcomes in appropriate charts.

Environmental Impact Assessments

- Have a serious environmental impact, they are subject to Directive 2001/42/EU.

-

Have a serious environmental impact, they are subject to Directive 2001/42/EU.

- Incorporate Natura 2000 sites and to prevent overlap, the environmental impact assessment shall be supplemented with the criteria of Article 6 of Directive 1992/43/ EU.

-

Incorporate Natura 2000 sites and to prevent overlap, the environmental impact assessment shall be supplemented with the criteria of Article 6 of Directive 1992/43/ EU.

The Mediterranean Action Plan

The Mediterranean coastal countries are included in the Mediterranean Action Plan (MAP), which is the first project implemented under the UN Regional Seas Program. In 1976, the Mediterranean Action Plan was ratified by fourteen Mediterranean countries and has since become institutionalized through the Barcelona Convention (https://ec.europa.eu/environment/marine/international-cooperation/regional-sea-conventions/barcelona-convention/index_en.htm (accessed on 8 May 2022)). The Mediterranean Action Plan was amended in 1995 (MAPII) and the revised Barcelona Convention has been in force ever since. The headquarters of the Mediterranean Action Plan—Coordination Unit is in Athens, being responsible for the Barcelona Convention Secretariat, and develops general strategies, the latest being the Mid-Term Strategy (MTS) (https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/6071/16ig22_28_22_01_eng.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2022)) 2016–2021. The goal of this strategy is “a healthy Mediterranean with marine and coastal ecosystems that are productive and biologically diverse contributing to sustainable development for the benefit of present and future generations”.References

- Ventura, A.M.F. Environmental Jurisdiction in the Law of the Sea; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020.

- Kastrisios, C.; Tsoulos, L. Maritime zones delimitation—Problems and solutions. In Proceedings of the International Cartographic Association Conference, Washington, DC, USA, 2–7 July 2017; Volume 1, pp. 1–7.

- European Commission. An Integrated Maritime Policy for the European Union; Commission Communication COM(2007) 575; Publications Office of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2007.

- European Commission. Blue Growth, Opportunities for Marine and Maritime Sustainable Growth; Commission Communication COM(2010) 494; Publications Office of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2012.

- European Commission. Europe 2020. A Strategy for Smart, Sustainable and Inclusive Growth; COM (2010) 2020 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 3 March 2010.

- European Commission. Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries, Marine Knowledge 2020: From Seabed Mapping to Ocean Forecasting: Green Paper; Publications Office of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2012; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2771/4154 (accessed on 8 May 2022).

- Shepherd, I. European efforts to make marine data more accessible. Ethics Sci. Environ. Politics 2018, 18, 75–81.

- European Parliament and Council Directive 2014/89/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 July 2014 Establishing a Framework for Maritime Spatial Planning. 2014. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2014/89/oj (accessed on 8 May 2022).