Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Jozsef Timar and Version 2 by Amina Yu.

Skin melanoma is traditionally considered one of the most immunogenic tumor types, based in part on its long-known feature of frequently containing a characteristic lymphoid infiltrate; furthermore, it may be the only tumor type for which spontaneous regression can occur in the primary tumor; this regression is assumed to be the consequence of antitumor immune response. More recent research and therapy results supported the unique immunological features of cutaneous melanoma from other aspects. It belongs to tumors with the highest tumor mutational burden (TMB), caused by high mutagen exposure (UV radiation).

- skin melanoma

- genomics

- molecular pathology

1. Molecular Epidemiology

Malignant melanoma is one of the most metastatic human cancers where a T1 sub-millimeter sized primary tumor of a ~106 cell population can have a significant metastatic potential, compared to most solid cancers, where a ten-times larger but similar T1 tumor of a population of 109 cells may not have it. Due to the novel lifestyles and global atmospheric changes, UV exposure of the skin has increased gradually, resulting in a paralleled increase in the incidence of melanoma [1]. In most European countries, melanoma can be found among the ten most frequent malignancies [1], and its prominent metastatic potential presents a significant burden for healthcare providers.

Malignant melanoma can develop from benign nevi or de novo. Considering the high incidence of benign nevi, the malignant transformation potential of these lesions is fortunately low. Meanwhile, nevi carry, at high frequency, the signature UV-induced mutation of BRAF (v-Raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1) at exon 15, providing evidence of the etiological factor behind [2]. Malignant melanoma, however, can develop on non-UV-exposed skin, mucosal epithelium or uvea, and these melanoma types usually lack the characteristic BRAF mutation.

Both skin and uveal melanoma can have familial form, but their genetic background is different. Besides the loss of CDKN2A (cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A), germline mutations of CDK4 (cyclin-dependent kinase 4), MITF (microphtalmia-associated transcription factor) and BAP1 (BRCA1-associated protein 1) are the most significant contributors for hereditary melanoma [3]. However, the picture became more complex with the discovery of germline alterations of the pigmentation-related and DNA-repair-related genes in the development of melanoma. As far as the pigmentation-related genetic factors are concerned, besides MITF mutations, the alterations of MITF-regulated MC1R (melanocortin-1 receptor), SLC45A2 (solute carrier family 45 member 2) and OCA2 (oculocutaneous albinism type 2) genes, as well as those of the melanosomal TYR (tyrosinase) and TYRP1 (tyrosinase-related protein 1) and DNA repair gene defects of TERT (telomerase reverse transcriptase) and APEX1 (apurinic/apyrimidinic endodeoxyribonuclease 1), are also significant contributors, increasing the risk of melanoma development. Furthermore, novel germline alterations at the chromosomal region of 1q21.3 involving ARNT (aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator) and SETDB1 (SET domain bifurcated histone lysine methyltransferase 1) were discovered lately as possible genetic risk factors for melanoma [3][4][5][6][3,4,5,6].

It is worth mentioning that, in the case ofor uveal melanoma, inherited homologous recombination or mismatch repair deficiencies due to PALB2 (partner and localizer of BRCA2) or MLH1 (MutL homolog 1) are the primary causes for heritability [7].

2. Molecular Classification

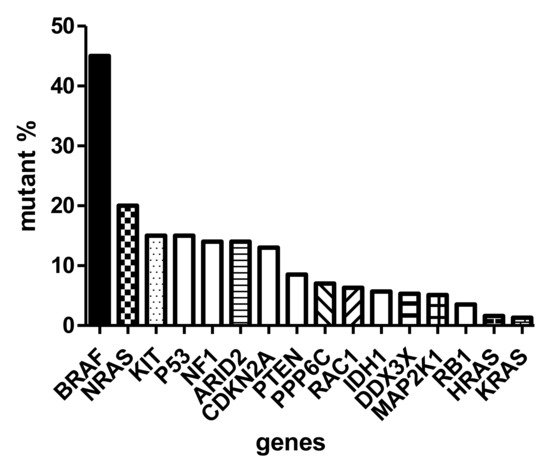

The sequencing of thousands of malignant melanomas worldwide defined the atlas of genomics of melanoma [8]. These analyses revealed that the most frequent gene defect of skin melanoma is the activating mutation of BRAF oncogene in exon 15/codon 600, characterizing almost half of these tumors. At a significantly lower frequency (~20%), the NRAS (neuroblastoma RAS viral (v-ras) oncogene homolog) oncogene is mutated in melanoma in exon 3/codon 61. Interestingly, almost with similar frequency (<15%) the KIT (KIT proto-oncogene, receptor tyrosine kinase) gene is also mutated in melanoma [9] (Figure 1). It has to be emphasized that the KIT receptor signaling pathway, containing NRAS and BRAF, is the dominating pathway in melanocytes (and evidently in melanoma), and it is responsible for activating the melanocyte-specific transcription factor MITF. As in other cancers, several oncosuppressor genes are mutated in melanoma, including TP53 (tumor protein p53), NF1 (neurofibromin 1), CDKN2A and PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog), at a similar relatively low frequency (~15%) (Figure 1). However, there are also genome-wide copy number alterations in melanoma: amplification affects the melanoma oncogenes, as well as CCND1 (cyclin D1) and MITF, while loss of heterozygosity (LOH) or complete loss may affect CDKN2A (p16) and PTEN [1]. Moreover, at much lower frequencies, chromosomal rearrangements affecting (beside PTEN) the kinase receptors ALK (anaplastic lymphoma kinase), RET (ret proto-oncogene) and NTRK (neurotrophic tyrosine receptor kinase) can also be detected [2].

Figure 1. Mutation spectrum of driver genes (oncogenes and suppressor genes) of skin melanoma based on TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas).

Similar to the traditional histological subclassification of melanoma, today the molecular classification is also possible where there are four major categories, the BRAF-mutant, the RAS-mutant, the NF1-mutant and the so-called triple wild-type forms [8]. It is now evident that a cancer is characterized by a relatively well-described set of driver oncogenes. Accordingly, the BRAF-mutant melanoma is a p16-lost or negative tumor, where TP53 mutations are relatively rare, but this is the form where the MITF and PD-L1 (programmed death ligand 1) genes are amplified. RAS-mutant melanomas are different from BRAF-mutant ones because neither MITF nor PD-L1 are amplified, but TP53 is more frequently mutated. The NF1-mutant melanoma can be called a suppressor gene melanoma, since, besides NF1, CDKN2A, RB1 (retinoblastoma 1) and TP53 genes are all mutant. Last but not least, the so-called triple wild-type melanomas are TP53-wild-type but carry mutations of MDM2 (mouse double minute 2 homolog) and CCND1 [10]. All four molecular subtypes are characterized by IDH1 (isocitrate dehydrogenase 1) mutation involved in epigenetic regulation, while ARID2 (AT-rich interaction domain 2) is wild type only in the triple wild-type form but mutated in the other subclasses, resulting in disturbances in chromatin remodeling and transcriptional control. It is another difference that the AURKA (Aurora kinase A) inhibitor PPP6C (protein phosphatase 6 catalytic subunit) gene is mutated in BRAF- and RAS-mutant subclasses exclusively.

The most frequent histological variant of skin melanoma is the superficial spreading melanoma (SSM) type. Other frequent variants are nodular melanoma (NM), acral lentiginous melanoma (ALM) and lentigo maligna melanoma (LMM). It is interesting that, in SSM or NM histological forms, the mutation order is BRAF > NRAS > KIT, while in the (acral-)lentiginous forms, the order of oncogene mutation frequency is KIT > BRAF > NRAS. Furthermore, ALM is characterized by chromosomal instability and a low mutational burden. There are rare histological variants of melanoma, with unique molecular signatures. The driver oncogene of deep penetrating melanoma is GRIN2A (N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor glutamate ionotropic receptor NMDA type subunit 2A), while the nevus-like melanoma is characterized by mutations of the lipid/AKT signaling pathway. A rare histological variant is the desmoplastic melanoma arising on chronic sun-damaged skin and is uniquely characterized by NFKBIE (NFKB inhibitor epsilon) promoter mutation, rare types of BRAF mutation and high tumor mutational burden (TMB) [11]. The blue nevus melanoma is a prototype of CDKN2A-lost tumor. As compared to these variants of (skin) melanoma, uveal melanoma is characterized by genetic alterations of the melanocortin receptor-1 signaling due to the mutations of GNAQ and GNA11 (guanine nucleotide-binding protein alpha subunit q and alpha subunit 11) genes [2].

3. Molecular Diagnostics

The identification of melanocytic lesions is based on specific markers of melanocytes which all associate with melanosomes not expressed by any other cell linages. Maturation of melanosomes is a four-step process, where lipid membranes of this organelle begin to contain melanosome-specific protein Pmel17/gp100, after which tyrosinase enzyme will be synthesized later, together with dopachrome tautomerase enzyme, and ultimately the organelle will contain MART-1/MelanA [12]. Based on this, the identification of melanocytic cells can be performed by immunohistochemistry detecting melanosomal proteins Pmel17/gp100, MART-1, or tyrosinase. Since the transcription of these genes is controlled by melanocytic MITF and SOX10 (Sry-related HMg-Box gene 10), the immunohistochemical detection of these transcription factors can also be used as a specific melanocytic marker. There is also a widely used, less specific protein marker of melanocytes, S100B (S100 calcium binding protein), which is expressed by neural cells as well [13].

Meanwhile, the diagnostic problem is frequently not the melanocytic origin of the lesion but the potential malignancy. Histopathology is the gold standard of differentiating these lesions, and the MPATHDx classification and its appropriate interpretation could help [14]. Immunohistochemical detection of the nuclear protein Ki67 is not suitable for this distinction since nevi, especially those mechanically damaged, may contain proliferating nevocytes. Until recently, morphological analysis of the melanocytic tumor cells served as the only diagnostic help, but today there are genetic techniques which could help in objectively defining the nature of the melanocytic lesions. One possibility is to use immunohistochemical markers of malignancy: two such markers have been evaluated and validated, p16 and PRAME. Loss of p16 protein alone may not be an optimal tool to differentiate benign or malignant lesions, but its combination with Ki67 and Pmel/gp100 may better suit the diagnostic need [14][15][14,15]. A new alternative to p16 is high PRAME protein expression, which has been validated relatively extensively [14]. Another possibility is to use a four-gene fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) probe applicable to formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) blocks. This probe set is composed of genes which characteristically suffer from copy number variations during malignant transformation of melanocytes: gene amplification generally occurs in RREB1 (rat responsive element binding protein 1) and CCND1 genes, while the loss of copies occurs in the case ofor CDKN2A and MYB (MYB proto-oncogene and transcription factor) genes (Table 3). A minimum of three copy number variations of these genes is required for malignancy definition [16]. Recently a gene expression signature was defined for melanoma, which could be applied to FFPE sections, as well, to discriminate melanomas from non-malignant melanocytic lesions. This molecular test (myPath; Myriad) is based on RNA evaluation of 14 genes, 7 of which are melanoma genes and 7 are tumor-microenvironment-associated ones [17].

4. The Molecular Background of Melanoma Progression

One of the outstanding questions in melanoma progression is how stable the oncogenic drivers are. Most of theour data come from investigating primary tumors or locoregional metastases, while very few genomic data are available concerning visceral metastases. It is known that melanoma is also a clonally heterogeneous tumor where driver mutant and wild-type clones are present as a mixture in the primary. It hasWe have analyzed the driver gene presence and the ratio of the mutant clones in melanoma metastases as compared to the primary tumors. It wasWe did not observed a complete loss of the driver oncogenes (BRAF or NRAS) in visceral metastases. However, itwe washave found an extreme heterogeneity concerning the relative clonal ratio of the driver clones, since it waswe found genetic evidence for all the three possible scenarios: maintenance of the original ratio, significant decrease of the driver clones and significant increase of the driver clones in metastases [18][27]. Accordingly, based on the clonal dominance of a driver clone in the primary tumor (or their extreme subclonality), one cannot predict the situation in the metastases which can be important when indicating target therapies.

The natural genetic progression of melanoma without therapeutic pressure is an important process. The data indicate that there are several novel mutations which emerge in metastases, such as those of BRCA1 (breast cancer gene 1), EGFR4 (epidermal growth factor receptor 4) and NMDAR2 (N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor 2). Since BRCA1 mutation results in homologous recombination deficiency, it may open the way to explore the potential use of PARP inhibitors in those instances. Furthermore, copy number changes are also emerging, affecting MITF or MET (MET proto-oncogene and receptor tyrosine kinase) (amplifications), or the loss of the suppressor PTEN, increasing the genetic diversity of the metastases as compared to the primary tumor [2][10][2,10]. Furthermore, copy number variations developing in metastasis-associated genes, NEDD9 (neural precursor cell expressed, developmentally downregulated 9), TWIST1 (Twist family BHLH transcription factor 1), SNAI1 (Snail family transcriptional repressor 1) and TEAD (transcriptional enhanced associate domain) are also significant genetic contributors of progression [2][10][2,10]. A recent one wastudy focuseding on the genetic analysis of visceral metastases of melanoma revealed organ-specific genetic alterations of progression. In the case of lung metastasis, copy number gains have been observed in several (19) immunogenic genes—most of them found to be expressed at protein levels (13)—termed as immunogenic mimicry, indicating a strong immunologic selection mechanism operational in this form of metastasis [19][28]. This observation may suggest that visceral metastases may not be equally sensitive to immunotherapy. In contrast to lung metastasis, in brain metastases of melanoma, besides TERT, amplifications of HGF (hepatocyte growth factor) and MET genes have been found, indicating the presence of a possible autocrine loop of signaling, offering a potential target therapy option for this type of metastasis. As compared to these organs, liver metastases did not contain many unique genetic alterations, except for amplifications of CDK6 (cyclin-dependent kinase 6) and MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) genes; both can now be targeted by clinically tested drugs [19][28]. Collectively, these genetic data offer new possibilities for target therapies of progressing melanoma and hopefully would initiate new types of clinical trials.