Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Catherine Yang and Version 3 by Chia-Chang Tsai.

Platform businesses, linking producers and consumers, have emerged as a very important industry. Meanwhile, value co-creation has become one of the critical issues concerning the operation of platform enterprises and the focus of researchers in this area. Platform businesses usually need to strengthen the interactions between all participants to maximize the commercial value.

- platform business

- value co-creation

1. Introduction

Numerous industries (e.g., those involving social networks, big data, platforms, and the Internet of things) have emerged in the current era of explosive Internet growth [1]. Among them, platform businesses have emerged as a very important industry that significantly affects global economy. For example, almost all of the top-ten companies in the world in terms of market value, such as Google, Apple, Amazon, Facebook, etc., have platform-related businesses. In addition, among the worldwide top-five start-up firms in terms of estimated future market value, four out of five are platform enterprises.

Platform enterprises link the markets from different sides, mainly producers and consumers [2]. Technological advances have facilitated the formation of an information value loop involving value creation, and the Internet has been both a catalyst and stage for numerous new businesses that explored the possibilities of value co-creation [3]. As defined by Prahalad and Ramaswamy [4], value co-creation is the collaboration between customers and suppliers in the co-conceptualization, co-design, and co-development of new products [4][5][6]. Although it is sometimes mentioned that value co-creation is a broad and abstract concept [7], a good example may let us easily understand it. de Oliveira and Cortimiglia [7] illustrated the value co-creation process of the DesignStyle platform, a clothes production network. The platform offers a place for fashion designers (as one side) to publicize their designs. On the other side, users and consumers of the community, can vote for the designs they enjoy the most, give comments for design modification, suggest for more creative ideas, etc. Through the interaction process, the designers receive useful feedback from the community and then make improvements and return better designs back to consumers and the community. Consumers not only gain access to innovative and exclusive fashion items but also even participate in the profits accrued from the platform and the production network. Here, a process of value co-creation can be observed.

The context of platform businesses can also be found in other industries. The increasing reliance of consumers on co-created content such as online postings or recommendations when making purchasing decisions [8] also affects the operation of platform businesses. Specifically, integrated functions promote consumer interactions in the purchasing process [9]. Platform environments should be conducive to value co-creation such that products can be leveraged to create activities that offer value to consumers [10][11].

The development of the platform economy model facilitates the development of a linear chain of industry value into a structure comprising multivalent value networks, such as a commercial loop in which the overall value chain involves symbiotic connections that drive enterprises to take market-driven and customer-driven approaches. Value co-creation refers to the generation of value that emphasizes various supplier–consumer interactions in the established network [12]. In contrast with producers, platform businesses may encounter bilateral or multilateral participants and must establish activities that effectively stimulate same-side or cross-side network effects such that the operational scale can expand and profits can be made as intended.

As indicated earlier, value co-creation activities include the conceptualization, co-design, and co-development of new product activities. Two main concepts or objectives are involved: first, co-creation of consumption experiences is the core of the value created by the business and the consumer, and second, the interaction between the participants in the value network is the fundamental path to the realization of value co-creation [4]. Numerous studies have examined consumers’ motivations for participating in the value co-creation process (e.g., [13][14][15]). In addition, some studies from the perspective of the impact of technology application and resource integration on value co-creation [3][16]. There are also some studies that consider value co-creation as a part of business-model innovation or the strengthening of network externalities [12][17]. These studies reveal how enterprises and consumers create value together and explore its effects on firm performance.

2. Platform Economy Model

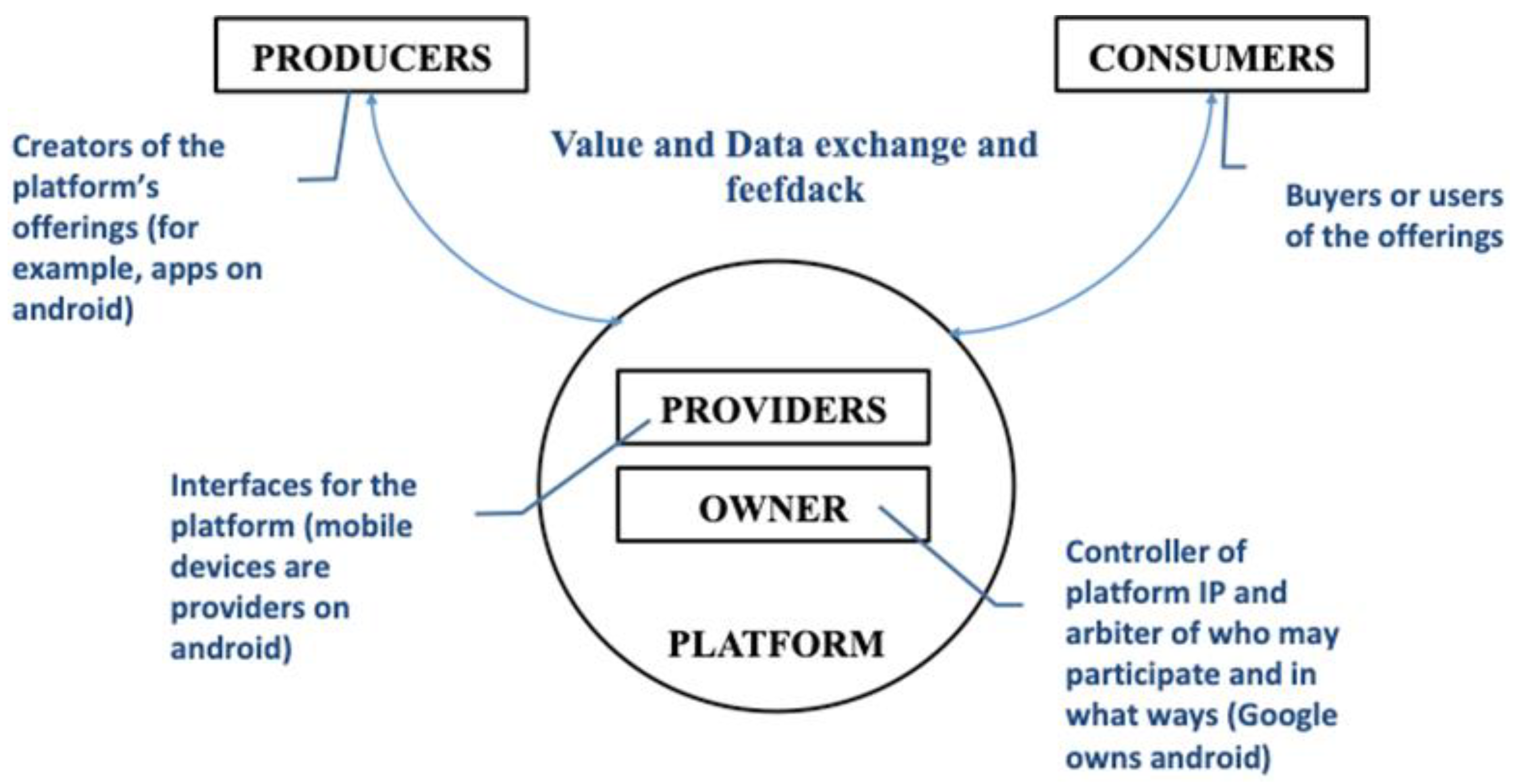

The platform economy model, which is relatively new, connects people, organizations, and resources to form an interactive ecosystem network of value creation [2]. Another essential function is the formation of linkages between or transactions among users to generate network effects. For example, the Uber platform connects drivers and passengers, the Airbnb platform connects hosts and guests, and the LinkedIn platform connects companies with job seekers. Such network effects are also called network externalities or demand-side economies of scale, meaning that the value of products or services rises with an increase in the number of customers using them. Van Alstyne et al. [2], based on the targets of networks, further categorize network effects into two types: same-side and cross-side effects. The same-side network effects are created when drawing users to one side helps attract more users to that side. For instance, as more people buy SONY’s PlayStation consoles, more new users will find it easier to trade games with their friends or find partners for online play [8]. Cross-side network effects imply that increasing the number of users on one side of the network makes it more (or less) valuable to the users on the other side. For example, in the transportation service platform, with more taxi drivers available, more new taxi riders will be expected. Shy [18] indicated that the first-mover advantage and winner-takes-all mechanisms are derived from network effects. Most platform businesses pay a high premium for the benefits of big data, the collection and application of which create a powerful and protective competitive barrier [19]. Van Alstyne et al. [2] listed three critical reasons why platform businesses succeed in replacing original industry players: First, platform businesses guide resources, whereas conventional businesses control them. Second, platform businesses place a premium on external interactions, whereas conventional businesses place a premium on internal activities. Third, platform businesses place a premium on ecosystem value, whereas conventional businesses do the same but for customer value. The researchers also articulated the relationships between ecosystem participants from an ecosystem perspective. As shown in Figure 1, the owner and the providers remain at the core of the platform ecosystem, and the producers and consumers are responsible for creating and using products, respectively.

Figure 1. Diagram of the relationships between participants in the platform ecosystem.

3. Value Co-Creation

The products offered by most platforms are actually services. A study by Ramírez [28] on the service industry noted that “the service process needs to be established on the basis of collaboration between the producers and consumers,” suggesting that both producers and consumers contribute to service value creation in terms of both the process and outcomes. According to Grönroos and Voima [29], interaction is the behavioral track of value co-creation. The concept grounding service-dominant logic is that the consumers, enterprises, and other stakeholders are all resource integrators among whom the interaction process enables value creation [30]. As defined by Prahalad and Ramaswamy [4], value co-creation is the collaboration between customers and suppliers in the co-conceptualization, co-design, and co-development of new products [4][5][6]. In customer relationship marketing, value co-creation further manifests the paradigm shift in transitioning toward a consumer-centric product logic [31]. The researchers also advocated that the consumer is the driving force of firm capacity expansion, suggesting that instead of focusing on creating core products, enterprises should devote more efforts to the provision of resources and activities to maintain their collaborative relationships with consumers in the long term. Sheth [32] distinguishes seven different forms of value co-creation according to the value created by different participants.3.1. Consumers Evolve Gradually from Users to Participants in Value Creation

As Prahalad and Ramaswamy [4] noted, as the business environment changes and networks develop, firm–consumer interactions become increasingly proactive. Through numerous channels, consumers can share their thoughts and opinions as well as resources such as time, knowledge, and skills with businesses, thereby promoting firm performance. This process gives both sides the opportunity to learn and grow. According to the service-dominant logic developed by Vargo and Lusch [5], consumers are starting to be regarded as value co-creators. The roles they play and the effects they generate have received considerable scholarly attention.3.2. Higher Levels of Consumer Need and Satisfaction Are the Key Source of Power in Value Co-Creation

Theory Z, advanced by Maslow [33], presented the concept of the sixth level of needs, which transcends humanity and spiritual needs. Maslow asserted that physiological needs, safety needs, belonging and love needs, and social needs (levels 1–4 in his hierarchy of needs) can be met through product purchases and service use. For example, buying everyday products can satisfy one’s physiological needs, whereas buying luxury products can satisfy social needs. By contrast, these actions cannot easily result in self-actualization or self-transcendence, which are attained through actual experiences. The incentivization of consumer behaviors such as participation, creation, sharing, and altruism by platform businesses enables consumers to channel their resources into value co-creation.3.3. The Level of Consumer Participation Affects Value Cocreation and Firm Competitiveness

As Lovelock and Wirtz [34] noted, the processes of service production and consumer participation are inseparable because of the co-occurrence of production and consumption, meaning that consumers participate in the transfer process of the services they receive. In platform businesses, the role of co-creator is naturally assumed when consumer participation is high; consumers’ preferences, interests, behaviors, and satisfaction (or lack thereof) are directly involved in the operational process. Firms are given real-time system feedback on consumer responses, allowing them to make timely adjustments. In short, this means that service value is co-created by the platform business and the consumers.3.4. Sharing among Consumers Gives Rise to New Value Creation Models

As Basole and Rous [35] asserted, numerous researchers believe that end-consumers, who dominate the behaviors in the value network to maximize co-created value for their own interests, are the most essential part of value creation; furthermore, numerous activities in the value network are generated for value realization by end-consumers [36]. Thus, the one-way generation of consumer value should not be among enterprises’ operational goals. Instead, consumers should be encouraged to create the value they require by taking advantage of services on offer from firms; this in turn elevates the value the enterprise derives. However, if companies fail to properly handle consumer behavior (especially complaints), in addition to being unable to create value with consumers, Value co-destruction is more likely [37]. Yu et al. [38] pointed out that enterprises can use platforms and mechanisms to create platform participants to obtain better performance and feedback.4. Summary and Research Gap

The majority of the literature has concentrated on the “platform business–consumer” interaction only, i.e., both “platform business–producer” and “platform producer–consumer” interactions have been almost completely neglected. In addition, most of the studies in this area are either conceptual or story-based articles without concrete evidence and data to support them. Consequently, this study aims to fill the research gap by investigating “all-around interactions”, including “platform business–consumer”, “business–producer”, and “producer–consumer” interactions and the relationships between each of interactions and the value co-creation performance. Thus, the research would develop a holistic framework of the value co-creation cycle in platform businesses. This effort and research direction echo the appeal by Yu et al. [38] that platform businesses should try to strengthen the interactions between and value co-creation among all platform participants in order to gain the maximal commercial value.References

- French, A.M.; Shim, J.P. The digital revolution: Internet of things, 5G, and beyond. Commun. Assoc. Inform. Syst. 2016, 38, 38–40.

- Van Alstyne, M.W.; Parker, G.G.; Choudary, S.P. Pipelines, platforms, and the new rules of strategy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2016, 2016, 54–60.

- Payne, E.H.M.; Peltier, J.; Barger, V.A. Enhancing the value co-creation process: Artificial intelligence and mobile banking service platforms. J. Res. Interact. Market. 2021, 15, 68–85.

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value creation. J. Interact. Market. 2004, 18, 5–14.

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. J. Market. 2004, 68, 1–17.

- Payne, A.; Storbacka, K.; Frow, P. Managing the co-creation of value. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 2008, 36, 83–96.

- De Oliveira, D.T.; Cortmiglia, M.N. Value co-creation in web-based multisided platforms: A conceptual framework and implications for business model design. Bus. Horiz. 2017, 60, 747–758.

- Tse, Y.K.; Zhang, M.; Doherty, B.; Chappell, P.; Garnett, P. Insight from the horsemeat scandal: Exploring the consumers’ opinion of tweets toward Tesco. Indus. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 1178–1200.

- Hajli, N.; Wang, Y.; Tajvidi, M.; Hajli, M.S. People, technologies, and organizations interactions in a social commerce era. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2017, 64, 594–604.

- Cayla, J.; Arnould, E.J. A cultural approach to branding in the global marketplace. J. Interact. Market. 2008, 16, 88–114.

- Wang, C.; Zhang, P. The evolution of social commerce: The people, management, technology, and information dimensions. Commun. Assoc. Inform. Syst. 2012, 31, 105–127.

- Cova, B.; Salle, R. Marketing solutions in accordance with the S-D logic: Co-creating value with customer network actors. Indus. Market. Manag. 2008, 37, 270–277.

- Payne, A.; Storbacka, K.; Frow, P.; Know, S. Co-creating brands: Diagnosing and designing the relationship experience. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 379–389.

- Roberts, D.; Hughes, M.; Kertbo, K. Exploring consumers’ motivations to engage in innovation through co-creation activities. Eur. J. Market. 2014, 48, 147–169.

- Xie, C.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Troye, S.V. Trying to prosume: Toward a theory of consumers as co-creators of value. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 2008, 36, 109–122.

- Schreieck, M.; Wiesche, M. How Established Companies Leverage IT Platforms for Value Co-creation- Insights from Banking. In Proceedings of the 25th European Conference on Information Science (ECIS), Guimaracs, Portugal, 5–10 June 2017.

- Fu, W.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, X. The influence of platform service innovation on value co-creation activities and the network effect. J. Serv. Manag. 2017, 28, 348–388.

- Shy, O. The Economics of Network Industries; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001.

- Viktor, M.S.; Kenneth, C. Big Data: A Revolution That Will Transform How We Live, Work, and Think; Eamon Dolan/Mariner Books: London, UK, 2014.

- Eisenmann, T.; Parker, G.; van Allstyne, W. Strategies for two-sided markets. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 92–101.

- Ali, S.A.; Wang, S.; Ming, X. Platform enterprise business model: Their essence and particularity. J. Res. Bus. Econom. Manag. 2018, 10, 1882–1889.

- Cusumano, A.; Gawer, A.; Yoffie, D.B. The Businesses of Platforms: Strategy in the Age of Digital Competition, Innovation, and Power; Harper Business School: Boston, MA, USA, 2019.

- Rietveld, J.; Schilling, M.; Bellavitis, C. Platform strategy: Managing ecosystem value through selective promotion of complements. Organ. Sci. 2019, 6, 1125–1163.

- Basoleand, R.C.; Karta, J. On the evolution of mobile platform ecosystem: Structure and strategy. Bus. Inform. Syst. Eng. 2011, 5, 313–322.

- Gawer, A. Building different perspectives on technological platforms: Towards an integrative framework. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 1239–1249.

- Zhu, F. Friends or foes? Examining platform owners’ entry into complementors’ spaces. J. Econom. Manag. Strat. 2019, 28, 23–28.

- Boudreau, K. Open platform strategies and innovation: Granting access vs. devolving control. Manag. Sci. 2020, 56, 1849–1872.

- Ramírez, R. Value co-production: Intellectual origins and implications for practice and research. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 49–65.

- Grönroos, C.; Voima, P. Critical service logic: Making sense of value creation and co-creation. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 2013, 41, 133–150.

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Service-dominant logic: Continuing the evolution. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 2008, 36, 1–10.

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. Co-opting customer competence. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2000, 78, 79–90.

- Sheth, J.N. Customer value propositions: Value co-creation. Indus. Market. Manag. 2019, 87, 312.

- Maslow, A.H. Theory Z. J. Trans. Psychol. 1969, 1, 31–47.

- Lovelock, C.; Wirtz, J. Services Marketing: People, Technology, Strategy, 5th ed.; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 2004.

- Basole, R.C.; Rouse, W.B. Complexity of service value networks: Conceptualization and empirical investigation. IBM Syst. J. 2008, 47, 53–68.

- Zeithaml, V.; Rust, R.; Lemon, K. The customer pyramid: Creating and serving profitable customers. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2001, 43, 118–142.

- Dolan, R.; Seo, Y.; Kemper, J. Complaining practices on social media in tourism: A value co-creation and co-destruction perspective. Tour. Manag. 2019, 73, 35–45.

- Yu, C.H.; Tsai, C.C.; Wang, Y.; Lai, K.K.; Tajvidi, M. Towards building a value co-creation circle in social commerce. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 108, 105476.

More