Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 4 by Saša Čaval and Version 3 by Saša Čaval.

Long-distance labor migrations had dire health consequences to both immigrants and host populations. Focusing on the quarantine station on Flat Island, Mauritius, this study analyzes a historical social setting and natural environment that were radically altered due to the implementation of health management.

- disease management

- quarantine

- historical archaeology

- colonial period

- medical history

1. Introduction

The outbreak of the epidemic disease in the Indian Ocean during the 19th century correlated with increased migration and improvements in steamship technology, forcing colonial governments to invest substantial resources in building and managing quarantine stations. These institutions were often set up in relatively isolated locations, especially uninhabited islets. Ships suspected of transporting infected commodities or sick people were then diverted to these islets, preventing them from docking at the regular ports. A resilient construction design of such facilities, originating in the Mediterranean world in response to plague epidemics during the medieval period [[1]], was adapted to a tropical environment and emerging infectious diseases. Modifications to the Mediterranean model were conditioned by two main factors: the specific disease in question, e.g., malaria, smallpox, and cholera, whose etiology and transmission were unknown at the time, and by the need to accommodate many people of various social classes and geographical origin (crew, travelers, and migrant workers) in a limited space, often for a considerable time.

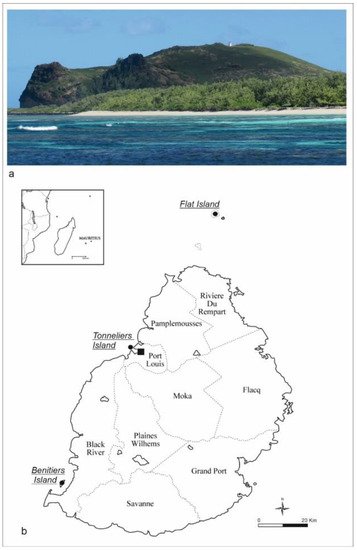

Flat Island is an exceptionally well-preserved quarantine station in the Indian Ocean, situated 12 km from the northern coast of Mauritius and used intensively during the second half of the 19th century (Figure 1a). Within a few years, from circa 1856, this uninhabited islet was drastically transformed. Environmental changes were wrought as a consequence of introducing invasive animals and plants, ultimately creating an anthropic landscape with built infrastructure. Flat Island quarantine station has significant heritage value as it has not been reused or repurposed since being abandoned after 1926. Comparable sites have been altered due to extensive use or conversion, such as leper colonies or military bases, resulting in a radical transformation of the original built landscape [[2]],[[3]]. The sudden abandonment of Flat Island at the onset of the 20th century left the station as an indelible material imprint, a witness to important structural facets of colonial health and disease management, as well as a unique example of cultural heritage.

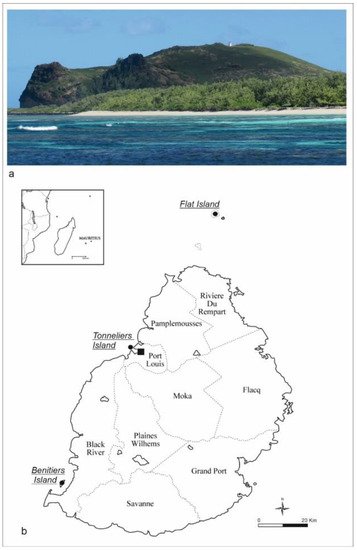

Figure 1. Flat Island—Mauritius: (a) The island from the southeast with the lighthouse at the highest elevation; (b) location of quarantine islands used during the 19th century in Mauritius.

The main aim of this research was to identify and study the built responses to health requirements in this specific region and historical moment. Examining the health-related rationale behind the built environment documented on Flat Island, this article presents the standing architecture and the functional configuration of the quarantine landscape, the design of which was clearly influenced by the dual forces of the prevailing medical theory and the exigent epidemic. The main activities involved in this study were archival research in the National Archives of Mauritius (NAM), followed by archaeological surveys and mapping of the standing architecture, which resulted in the collection of copious historical and archaeological data. The standard landscape archaeology and spatial methods, such as drone mapping, photogrammetry, GPS, and total station surveys, were combined with orthorectification and 3D modelling, returning detailed documentation of the built environment. Furthermore, the assessment and comparison of the original architectural drawings from the 1850s with the constructed buildings, as well as repairs and modifications during their use, grants an understanding of how construction plans were adjusted for emerging practical needs. Through specific improvements, such as the use of concrete instead of wood and the implementation of a water piping system, it is possible to follow the spatial and social negotiations in the long-term use of the site. Freshwater was considered an essential element: the major structural restoration and facility implementations aimed to secure healthy conditions and sustainability requirements through time. The construction of latrines for women in the quarantine camps after 1877 responded to specific social needs, possibly determined by new demands from a growing migrant female population. Flat Island’s spatial and functional organization reflects both the medical beliefs of the time and the social biases driven by the colonial elite, affecting the human behavior of migrants. Few colonial officers dictated regulations on which large numbers of quarantined indentured laborers, mostly from Southeast Asia, had to comply. The result of all these actions can be summarized in the concept of “healthscaping”, defined as “the physical, social, legal, administrative and political process of regulating and managing the built and natural environment to promote wellbeing” [[4]]]. In this article, we focus on the physical and social processes enacted in the founding and management of the station to consider the gap between the theoretical claim and the practical output realized by British colonizers in promoting public health practices. Although general rules of preventive healthcare were well established and detailed by written sources, their material implementation in the built landscape was more varied, based on social discrimination between Europeans and immigrants.

2. Historical Background

Modern ideas of quarantine are linked to globalization. Although the practice of isolating miasmatic or polluted matter far predated the outbreak of epidemic diseases, especially plague during the Middle Ages; the earliest quarantine practices were developed during this time. Believing that miasma (“bad air”) caused disease did establish the connection between location and transmission of diseases [[25]]. Quarantine measures were first introduced in 1377 in the Republic of Ragusa, Dalmatia (present-day Dubrovnik in Croatia), with a thirty-day isolation period for all incoming ships, suspected of carrying disease on board. The screening and disinfection practices were initially implemented by fumigating goods and only secondarily by isolating animals and people. In Venice, the “trentino” was extended to “quarantino” (quaranta giorni, i.e., forty days) in the late 1400s, imposed on ships and their crews before they could dock in the city [[56]], [[[6]7]]]. Over the centuries, the practice of quarantine spread all around Europe and farther, in the colonial worlds becoming a recurrent matter of political and economic debate, as well as a source of abuse, which can still be observed in current times [[[5]],[[[7]8]],[[[89]], [[310]],[[411]].

The quarantine system was operational in the colonies in the Indian Ocean from the mid-19th century onwards. After the abolition of slavery in the 1830s, a mass of indentured laborers replaced the enslaved people [[[9]]12]]. Since this, it was encouraged mainly by the Indian government, as the vast majority of the indentured diaspora originated from India.

In the Mascarene islands, between the 18th and the 19th centuries, three main diseases required the use of quarantine: smallpox, cholera, and malaria. Their etiology and incubation period were unknown to contemporaneous physicians. Smallpox was the primary cause of epidemics in enslaved communities during the 18th century, but a coherent system of quarantine stations was never established; instead, temporary isolation or so-called maritime quarantine was applied to incoming ships. These were left to anchor outside of the main port of Port Louis, particularly in Belle Buoy and Grand Riviere, farther south. In the 18th century, temporary stations, the first quarantine depots, were set up on the islands of Tonneliers near Port Louis, and Bénitiers in the south, and housed people in provisional shelters without any medical care (Figure 1b). After the introduction and widespread use of the smallpox vaccine in the 19th century, cholera became the primary disease that mandated quarantine [[513]] and was closely associated with indentured laborers from India. Regulatory changes in health management, new locations, and policies for quarantine inspection and detention were a result of the escalating intercontinental labor diaspora. For many immigrants, especially those coming from Southeast Asia, a quarantine station became the first place of contact with their new home, so the quarantine system was converted from its original health-oriented role into a socially controlling system [[1014]].

3. Study Area

In the second half of the 19th century the Mauritian colonial government used Flat and Gabriel islands, two neighboring islets 12 km off the north coast of Mauritius, to isolate disease-ridden indenture ships. In the beginning, these two stations were confinement sites, with temporary wooden shelters, rather than actual quarantine stations. Hence, the main difficulty for people forced into quarantine was not the risk of contagious disease but the certainty of inadequate living conditions. A case in point occurred on Gabriel Island in January 1856, when around 300 indentured immigrants died due to harsh conditions, exacerbated by the cholera epidemic [[[1115]]]. This human disaster sparked a temporary diplomatic dispute leading to the cessation of immigration and a demand from the Indian government for a permanent quarantine station on the mainland [[613]].

In the following years, under pressure from the Indian government, the Mauritian quarantine system was reorganized by setting up two permanent quarantine stations: one on Flat Island for cholera and another on the mainland, at Pointe aux Cannoniers, for all other diseases [[716]]. Both stations included dormitories, hospitals, a morgue (called dead house), water cisterns, latrines, and a graveyard. Environmental factors were considered crucial in planning these institutions: the quarantine stations were positioned on the coast, with specific buildings constructed to help with disinfection and sanitization procedures. Particular attention was given to the orientation and ventilation of buildings, especially hospitals and infirmaries, since miasmas were considered to cause infectious diseases until the 1880s, when the emergence of germ theory marked a new understanding of disease etiology [[1217]]].

References

- Crawshaw, J.L.S. Plague Hospitals: Public Health for the City in Early Modern Venice; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012. Crawshaw, J.L.S. Plague Hospitals: Public Health for the City in Early Modern Venice; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012.

- Schiappacasse, P.A. Archaeology of Isolation: The 19th Century Lazareto de Isla de Cabras, Puerto Rico. Ph.D. Thesis, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY, USA, 2011.

- Longhurst, P. Contagious Objects: Artefacts of Disease Transmission and Control at North Head Quarantine Station, Australia. World Archaeol 2018, 50, 512–529.

- Geltner, G. Healthscaping a medieval city: Lucca’s Curia viarum and the future of public health history. Urban Hist. 2013, 40, 395–415. Geltner, G. Healthscaping a medieval city: Lucca’s Curia viarum and the future of public health history. Urban Hist. 2013, 40, 395–415.

- Krekić, B. Dubrovnik in the 14th and 15th Centuries: A City between East and West; University of Oklahoma Press: Norman, OK, USA, 1972.Varlik, N. Plague and Empire in the Early Modern Mediterranean World; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015.

- Biraben, J.N. Les Hommes Et La Peste En France Et Dans Les Pays Européens Et Méditerranéens; Mouton: La Haye, The Netherlands, 1975; Volume 1Krekić, B. Dubrovnik in the 14th and 15th Centuries: A City between East and West; University of Oklahoma Press: Norman, OK, USA, 1972.

- Arole, S.; Premkumar, R.; Arole, R.; Maury, M.; Saunderson, P. Social stigma: A comparative qualitative study of integrated and vertical care approaches to leprosy. Lepr. Rev. 2002, 73, 186–196.Biraben, J.N. Les Hommes Et La Peste En France Et Dans Les Pays Européens Et Méditerranéens; Mouton: La Haye, The Netherlands, 1975; Volume 1.

- Lesshafft, H.; Heukelbach, J.; Barbosa, J.; Rieckmann, C.N.; Liesenfeld, O.; Feldmeier, H. Perceived social restriction in leprosy-affected inhabitants of a former leprosy colony in northeast Brazil. Lepr. Rev. 2010, 81, 69–78. Arole, S.; Premkumar, R.; Arole, R.; Maury, M.; Saunderson, P. Social stigma: A comparative qualitative study of integrated and vertical care approaches to leprosy. Lepr. Rev. 2002, 73, 186–196.

- Hopper, M. Liberated Africans in the Indian Ocean World. In Liberated Africans and the Abolition of the Slave Trade, 1807–1896; Anderson, R., Lovejoy, H.B., Eds.; University of Rochester Press: Rochester, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 271–294.Lesshafft, H.; Heukelbach, J.; Barbosa, J.; Rieckmann, C.N.; Liesenfeld, O.; Feldmeier, H. Perceived social restriction in leprosy-affected inhabitants of a former leprosy colony in northeast Brazil. Lepr. Rev. 2010, 81, 69–78.

- Chase-Levenson, A. The Yellow Flag: Quarantine and the British Mediterranean World, 1780–1860, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. Tognotti, E. Lessons from the history of quarantine, from plague to influenza A. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2013, 19, 254–259.

- Report 1857. Report of the Committee Appointed by His Excellency the Governor, to Inquire into and Report upon: The Probable Cause or Causes of the Recent Outbreak of Cholera in the Island of Mauritius in March 1856; Plaideau, H., Ed.; Government Printer: Port Louis, Mauritius, 1857.Chu, I.Y.-H.; Alam, P.; Larson, H.J.; Lin, L. Social consequences of mass quarantine during epidemics: A systematic review with implications for the COVID-19 response. J. Travel Med. 2020, 27, taaa192.

- Beattie, J. Imperial Landscapes of Health: Place, Plants and People between India and Australia, 1800s–1900s. Health Hist. 2012, 14, 100–120. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5401/healthhist.14.1.0100 (accessed on 25 October 2021). Hopper, M. Liberated Africans in the Indian Ocean World. In Liberated Africans and the Abolition of the Slave Trade, 1807–1896; Anderson, R., Lovejoy, H.B., Eds.; University of Rochester Press: Rochester, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 271–294.

- Boodhoo, R. Infectious Disease and Public Health Mauritius 1810–2010; ELP Publications: Vacoas-Phoenix, Mauritius, 2019.

- Chase-Levenson, A. The Yellow Flag: Quarantine and the British Mediterranean World, 1780–1860, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020.

- Report 1857. Report of the Committee Appointed by His Excellency the Governor, to Inquire into and Report upon: The Probable Cause or Causes of the Recent Outbreak of Cholera in the Island of Mauritius in March 1856; Plaideau, H., Ed.; Government Printer: Port Louis, Mauritius, 1857.

- Boodhoo, R. Health, Disease and Indian Immigrants in Nineteenth Century Mauritius; Aapravasi Ghat Trust Fund: Port Louis, Mauritius, 2010.

- Beattie, J. Imperial Landscapes of Health: Place, Plants and People between India and Australia, 1800s–1900s. Health Hist. 2012, 14, 100–120. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5401/healthhist.14.1.0100 (accessed on 25 October 2021).

More