Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Emilia Vassilopoulou and Version 2 by Vivi Li.

The basis of the MedDi model is the diet of the people of the island of Crete in the early 1950s; it is characterized by a high plant/animal food ratio, and, compared with other populations, it is linked with a markedly low prevalence of chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disease (CVD), breast cancer, colorectal cancer, diabetes mellitus (DM), obesity, asthma, erectile dysfunction, depression and cognitive decline, and with a high life expectancy.

- Mediterranean diet

- asthma

- atopy

- antioxidants

- lipids

- vitamin

1. Introduction

The prevalence of atopy and asthma has increased substantially in most developed countries [1][2][3][1,2,3], a trend potentially influenced by both genetic and environmental factors [4]. While our genetic profile is unlikely to have altered much in the last decades, our living conditions and habits have undergone major changes [5]. Environmental exposures are, therefore, considered to be the key culprit for the escalation [6]. As environmental factors may be amenable to intervention, their identification is important in efforts to curtail the current allergy epidemic. The observation that the rate of asthma has risen concomitantly with the degree of affluence [7] has kindled a search for specific cultural influences. It has been documented that culture shapes the asthma experience, its diagnosis and management, relevant research, and the politics determining funding [8].

As initially proposed by Burney [9] and later supported and extended by Seaton [10], changes in dietary habits could be partly responsible for the observed increase in atopic disease [11]. The rise in the prevalence of asthma in Western societies has coincided with marked modifications in the diet of these populations, leading to theories of a link between nutritional factors and asthma/atopy [12][13][14][15][16][17][18][12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. Among other factors, a link between a diet high in advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) and AGE-forming sugars and an increase in food allergy was proposed by Smith and colleagues [2]. It is thought that AGEs might function as a “false alarm” for the immune system against food antigens. In the pathogenesis of asthma/allergic airway inflammation, a receptor specific for the AGEs (RAGE) appears to be a critical participant [19].

A trend towards a lower prevalence of asthma in the Mediterranean region was identified in 1998 by the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) [20], and epidemiological evidence has indicated that the Mediterranean diet (MedDi) might be protective against asthma [21][22][23][24][21,22,23,24].

Hence, a reasonable hypothesis is that adherence to the MedDi may modulate asthma pathogenesis, but even with a substantial body of research evidence, findings on such an association are far from conclusive. To account for the discrepant results, a variety of limitations, cultural, geographical, biological and methodological, must be taken into consideration. In this comprentry, researchershensive narrative review, we present and discuss the currently available evidence on the relationship of the MedDi with asthma/atopy, researcherswe underscore the research pitfalls, and researcherswe propose ways forward, including possible interventions. ResearchersWe have opted to focus on the “contemporary Greek MedDi”, rather than the general archetype of the “Mediterranean diet of the previous century”, in an effort to circumvent one of the key research limitations, which is the diversity of the MedDi.

2. Obstacles to the Validation of Associations

2.1. Issue No. 1: What Is a “Mediterranean Diet”?

The basis of the MedDi model is the diet of the people of the island of Crete in the early 1950s [25]; it is characterized by a high plant/animal food ratio, and, compared with other populations, it is linked with a markedly low prevalence of chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disease (CVD), breast cancer, colorectal cancer, diabetes mellitus (DM), obesity, asthma, erectile dysfunction, depression and cognitive decline, and with a high life expectancy [26]. The typical MedDi pattern is composed of the following [25][27][28][25,27,28]: (1) daily consumption of refined cereals, and their products (bread, pasta, etc.), fruit (4–6 servings/day), vegetables (2–3 servings/day), olive oil (as the principal source of fat), wine (1–2 glasses/day) and dairy products (1–2 servings/day); (2) weekly consumption of fish, legumes, poultry, olives and nuts (4–6 servings/week), and (3) monthly consumption of red meat and meat products (4–5 servings/month). In sum, the MedDi is characterized by a high intake of plant foods such as fruits, vegetables, cereals, legumes, olive oil and nuts, a high to moderate intake of fish and seafood, a moderate to low intake of dairy products and wine, and only small quantities of red meat. MedDi is, by most accounts, a generalization, if not a misnomer, as several variations are observed around the Mediterranean basin [29], which, unsurprisingly, reflects the diversity in religious, economic and social structures in these areas. For example, Muslims abstain from pork and wine, while Greek Orthodox populations usually avoid eating meat on Wednesdays and Fridays and during the 40-day fasting periods before major religious festivals. Differences stem also from the local availability of foodstuffs, which was a critical issue until some decades ago, as food transfer was arduous, and people had to rely on what they could produce and procure locally. In the 1960s, therefore, even different regions within the same Mediterranean country followed their own, distinct, dietary patterns [30]. Food transport is no longer a factor, but regional production continues to dictate, to some extent, the local cuisine. In parallel, food consumption patterns have changed during the last 50 years in most regions, including Crete [31], with adaptation to Westernized dietary patterns, leading to a poor MedDi quality index [32][33][34][32,33,34]. The cardinal feature of a Mediterranean-type diet, olive oil, however, still serves as the principal source of dietary fat in Crete, as in many Mediterranean regions, providing the precious monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) and polyphenols [35][36][35,36].2.2. Issue No. 2: Nutrients, Foods or Dietary Patterns?

Diet is a highly complex exposure variable. Traditional research approaches, focusing on individual nutrients, generate methodological pitfalls, as they may fail to take into account important nutrient interactions [37][38][37,38]. Perceived “healthy” foods contain numerous beneficial nutrients, necessitating stringent analytical adjustment to uncover their individual actions [39], but this approach would require sample sizes in excess of those reported in most published studies [40][41][40,41]. There are also conceptual issues; humans consume concurrently a variety of foods containing a constellation of nutrients, and the clinical relevance of the presumed effects of single nutrients is, therefore, questionable. It is reasonable to assume that any beneficial clinical effect is mediated through the combined action of several dietary agents [42][43][42,43], and the implication is that large-scale dietary manipulation, rather than single nutrient supplementation, would be a more promising approach for asthma-related research and possible disease prevention. In practice, the investigation of dietary patterns, rather than individual nutrients, is a paradigm that is gaining momentum [44]. To that end, the use of diet scores has been recommended, and various different MedDi scores have been constructed and used in research, including the Mediterranean diet score (MDS),the Mediterranean diet scale (MDScale) and the Mediterranean food pattern (MFP) [28][45][46][28,45,46]. All these indices show satisfactory performance in assessing adherence to the MedDi [47], and the MDScale and MedDi show correlation with olive oil and fiber constituents, while the MDScale shows correlation with waist-to-hip ratio and total energy intake [35]. It is of note that individual foods and constituents within the MedDi, specifically fish and olive oil appear to be particularly beneficial for asthma outcomes [48][49][50][48,49,50].2.3. Issue No. 3: Observation versus Intervention

Findings on a possible correlation between diet and asthma are conflicting, but it appears that most of this disparity derives from a single methodological feature, namely, whether the studies are observational or interventional. A consistent theme in the epidemiological/cross-sectional literature is that of a beneficial effect of several dietary agents on asthma/atopy; this is in contrast with randomized clinical trials/supplementation studies, which yield inconclusive results. Several theories have been proposed to explain this discrepancy, such as the short duration of supplementation, or the requirement of an underlying deficiency for supplementation of the nutrient to show effects [51], both of which have been partly overthrown [12]. It has been suggested that positive observational evidence may stem from prenatal maternal nutrition, which could define the asthma risk of the offspring, and also serve as a model for the dietary habits of the child/grown adult [52][53][52,53]. In effect, observational studies could erroneously link the diet of the child/adult with favorable effects, when the defining factor may, in fact, be the maternal diet during pregnancy; this would also explain the failure of postnatal interventions. Although this theory has not been confirmed, it is plausible that the maternal prenatal diet may modify the future asthma risk of the child via epigenetic “programming” of the fetal lung and immune system [54]. Interest in the role of modifiable nutritional factors specific to both the prenatal and the early postnatal life is increasing, as during this time the immune system is particularly vulnerable to exogenous influences. A variety of perinatal dietary factors, including maternal diet during pregnancy, duration of breastfeeding, use of special milk formulas, timing of the introduction of complementary foods, and prenatal and early life supplementation with vitamins and probiotics/prebiotics, have all been addressed as potential targets for the prevention of asthma [55]. Breastfeeding is a sensitive period, and knowledge of its effects has, to date, been gained observationally [56][57][58][56,57,58]. The results related to the possible protection gained through breastfeeding against allergies and asthma have been inconsistent [59][60][59,60]. Current evidence suggests a protective role of exclusive breastfeeding in atopic dermatitis (AD), related to atopic heredity [61]. Reduced intake of omega 3 (n-3) polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) may be a contributing factor to the increasing prevalence of wheezing disorders [62][63][62,63], and a higher ratio of n-6/n-3 PUFAs in the maternal diet, and maternal asthma, increase the risk of wheeze/asthma in the offspring [63]. The effect of n-3 PUFA supplementation in pregnant women on the risk of persistent wheeze and asthma in their offspring has been assessed. Supplementation with n-3 long-chain (LC)PUFA in the third trimester of pregnancy was shown to reduce the absolute risk of persistent wheeze and lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) in infancy [64][65][64,65], and the risk of asthma by the age of 5 years [66], and later in life [67].3. Evaluation of Dietary Constituents

Two major research hypotheses have been proposed to explain the link between dietary constituents and asthma: the lipid hypothesis and the antioxidant hypothesis. Both hypotheses are based on foods that are hallmarks of the MedDi. A third one, the anti-inflammatory hypothesis emerges to merge and corroborate the other two.3.1. The Lipid Hypothesis

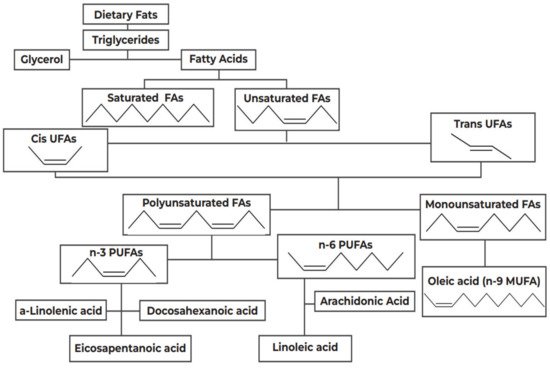

In 1997, Black and Sharpe [68] originally suggested that changes in the intake of fatty acids (FAs), in both type and quantity, has contributed to the rise of asthma and atopy in the West. FAs are categorized as saturated or unsaturated, depending on the presence of double carbon bonds, as shown in Figure 1. Unsaturated FAs are classified into MUFAs, such as oleic acid, and PUFAs, which are further divided into subgroups, the n-6 and the n-3 PUFAs, based on the position of the double carbon bonds.

Figure 1.

Categorization of dietary fats. FA: Fatty Acids; PUFAs: Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids; MUFA: Monounsaturated Fatty Acids.

Table 1. Synopsis of the effect of monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) and n3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), and vitamins A, C and E on asthma and atopy outcomes, and the effect of Vitamin D on bronchial and atopy outcomes.

| Type of Lipids | Asthma/Atopy Outcomes | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| MUFAs | • Reduced risk of asthma/atopy | [70][92][70,92] |

| • Cell membranes support-reduced AD | [93] | |

| n-3 PUFAs (fish oils) | Prenatal | |

| • reduced risk of wheeze/asthma | [62][63]63[66][67],66[87],67[94][62,,87,94] | |

| • respiratory infections | [65] | |

| • atopy | [90][91][95][90,91,95] | |

| • AD | [96] | |

| Postnatal | ||

| observational: protection on asthma, atopy | [26][69][97][98][99][100][101][102][103][26,69,97,98,99,100,101,102,103] | |

| interventional: inconclusive on | ||

| • AD | [104][105][104,105] | |

| • asthma/wheeze | [66][106][111][112][113][66,106107],107[108],108[109],109[110],110[,111,112,113] | |

| • worsening on asthma in aspirin-intolerant patients | [114][114[115],115] | |

| n-6 PUFAs | Prenatal | |

| no effect or increased risk of | ||

| • AD | [43][116][117][43,116,117] | |

| • atopy | [118] | |

| Postnatal | ||

| • contradictory results on AD and asthma | [119][120][121][122][119,120,121,122] | |

| Trans-fat | Increased risk of asthma/atopy | [123][124][125][126][123,124,125,126] |

| Saturated FAs | Increased | |

| • bronchial hyperresponsiveness | [127] | |

| • asthma | [128] | |

| • atopy | [129] | |

| Vitamins C, E, A (fruits and vegetables) | Prenatal | |

| • observational: conflicting evidence on asthma/atopy | [130] | |

| • interventional: lack of evidence | ||

| Postnatal | ||

| • observational: generally favorable on asthma/wheeze, atopy | [43][50][131][132][133][134][135][136][137][138][139][140][43,50,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140] | |

| • interventional: conflicting evidence, nutrient specific | [12][141][146][147][148][12,141142],142[143],143[144],144[145],145[,146,147,148] | |

| Vitamin D | Prenatal | |

| • observational: generally favorable on bronchial outcomes | [12][13][149][150[153][12,13][,149151][,150152,151],152,153] | |

| • interventional: favorable when mother has asthma | [154][155][156][154,155,156] | |

| Postnatal | ||

| • observational: favorable on asthma/atopy | [157][158][159][157,158,159] | |

| • interventional: favorable on asthma/atopy | [160][161][160,161] |

3.2. The Antioxidant Hypothesis

The antioxidant hypothesis was proposed in 1994 by Seaton and colleagues [10], who suggested that a Westernized diet, progressively deficient in antioxidants, could be held accountable for the rising prevalence of atopy. Accumulating evidence indicates the possible involvement of oxidative stress in the pathophysiology of inflammatory disorders such as asthma and allergic rhinitis [44][162][163][44,208,209].

The lungs are susceptible to oxidative injury because of their high oxygen environment, large surface area and rich blood supply [164][210]; hence the respiratory system has evolved elaborate antioxidant defenses, including three key antioxidant enzymes, superoxide dismutase and glutathione peroxidase and catalase, and numerous non-enzymatic antioxidant compounds, including glutathione, vitamins C and E, α-tocopherol, lycopene, β-carotene, and others. Disruption in the redox balance may favor asthma induction [165][211].

Maternal consumption of a MedDi rich in fruits, vegetables, fish and vitamin D-containing foods has been shown to exert possible benefit against the development of allergies and asthma [21], or at least to protect small airway function, in childhood [166][212]. Fruit and vegetables commonly consumed by Mediterranean populations [24], particularly those produced locally, such as oranges, cherries, grapes and tomatoes [167][168][213,214], are rich in antioxidants, such as glutathione, vitamin C, vitamin E, vitamin A and provitamin A carotenoids (α-carotene, β-carotene, β- cryptoxanthin, lutein/zeaxanthin and lycopene), and polyphenols (primarily flavonoids) [44][168][44,214]. Numerous observational studies have suggested a protective effect of high postnatal (childhood/adult) consumption of such foods against asthma/allergic rhinitis [50][169][50,215] and atopy/AD [132][167][132,213].

Interpretation of these findings should not overlook the effect of specific micronutrients on the outcomes investigated. For instance, low dietary vitamin C intake, and low levels of serum such as corbate have been associated with current wheeze [133], asthma and reduced ventilatory function in numerous epidemiological studies, possibly confirming that vitamin C is a major bronchial antioxidant [134][135][134,135]. McEvoy and colleagues in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of vitamin C supplementation to pregnant smokers showed better pulmonary function at 3 months of age in the offspring of mothers taking vitamin C [170][216].

Supplementation with vitamin C, however, of even up to 16 weeks, has generally yielded poor results [136], as also concluded by a Cochrane review [137]. Vitamin C supplementation may benefit exercise-induced bronchoconstriction [134], and treatment with high doses of intravenous vitamin C was suggested to control allergy symptoms [138]. The compounded evidence points towards a protective effect of a longstanding habitual diet rich in vitamin C, rather than short-or medium-term supplementation and/or intervention in already established asthma [43][133][43,133].

The case for vitamin E is similar; vitamin E is the principal defense against oxidant-induced membrane injury [171][217]; its dietary sources are olive oil, olives, nuts and avocado [172][218], which are key constituents of the MedDi. Vitamin E, in contrast to vitamin C, exerts additional non-antioxidant immune-regulating action in the form of the modulation of IL-4 gene expression, production of eicosanoid and IgE, neutrophil migration and allergen-induced monocyte proliferation [173][174][219,220].

Intervention studies in the postnatal setting have produced conflicting findings [141][142][143][141,142,143]. Considerable epidemiological evidence suggests a protective role against asthma for vitamin E [143] although there are also reports of no benefit [144], possibly indicative of the opposing regulatory effects of the tocopherol isoforms of vitamin E [145]. Favorable reports have been produced in the prenatal observational setting, with some studies showing a protective effect of high maternal prenatal consumption on asthma/AD outcomes in the offspring [130]. This may reflect the immune modulating action of vitamin E during a critical period for immune system ontogeny. As with vitamin C, habitual dietary intake of vitamin E may protect against asthma, but this may be due to interaction between closely related nutrients; for example, concurrent vitamin C and E supplementation was observed to protect against bronchoconstriction in one cross-sectional study in preschool children [139], but firm conclusions could not be drawn on the effectiveness of vitamin C and E on either asthma control or exercise-induced bronchoconstriction, in a systematic review by Wilkinson and colleagues [140].