Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Jessie Wu and Version 1 by Vadims Parfejevs.

Proper functioning of the digestive system is ensured by coordinated action of the central and peripheral nervous systems (PNS). Peripheral innervation of the digestive system can be viewed as intrinsic and extrinsic. The intrinsic portion is mainly composed of the neurons and glia of the enteric nervous system (ENS). The extrinsic part is formed by sympathetic, parasympathetic, and sensory branches of the PNS with Schwann cells (SCs) being the chef glial cells. SCs are a crucial component of digestive tract innervation, and a great deal of research evidence highlights the important status of these glial cells in health and disease.

- Schwann cells

- digestive system

- pancreas

- cancer

1. Oral Cavity

The oral cavity is densely innervated by branches of the trigeminal nerve that has sensory and motor functions [1]. Chronic and acute orofacial pain conditions such as headache, and dental and cancer-related pain affect many people worldwide [2]. Oral cancers are among the 10 most prevalent cancers, have a poor prognosis, and are associated with intense pain [3][4]. The most common type of mouth tumours is oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC), which represents around 90% of all cases [5]. Loss of TP53, a gene most commonly mutated in head and neck cancers, further promotes innervation in mouse oral epithelia, while in patients with OSCC, increased innervation correlates with worse overall survival [6]. In fact, perineural invasion (PNI) is a common pathophysiological feature observed in up to 60% of OSCCs and increases the risk of lymph node metastasis [5][7].

Glia are recognised as mediators of orofacial pain [8][9], and several studies suggest that SCs are involved in the increased nociception [10][11] and nerve invasion [12][13] observed in oral malignancies. One of the proposed mechanisms is the activation of SCs in response to tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) secreted by OSCC cells. This activation, in turn, stimulates TNFα and nerve growth factor (NGF) production by SCs themselves. TNFα overexpression is found in oral cancer tissues and is indeed correlated with elevated pain, while supernatants from activated SCs can increase facial allodynia in mice [11]. The TrkB/BDNF signalling axis is involved in the oral cancer PNI process, since modulation of this pathway in co-culture studies regulates SC—tumour cell interaction, and influences cell migration and differentiation [12][13]. Additionally, tooth SCs have a special status in dental pulp where they perform stem cell [14] functions, and modulate immune response [15] and nociception [9]. For a broader discussion of this topic, wresearchers refer the reader to a recent review [16].

2. Esophagus

The esophagus is innervated by many inputs, including vagal motor neurons, sensory neurons, and local enteric neurons [17][18]. Imbalance of inhibitory and excitatory neural activity [19] as well as sensitisation of esophageal afferent neurons by inflammatory mediators and endogenous substances (hydrogen, potassium ions, 5-HT, bradykinins, prostaglandins, etc.) [20], leads to various esophageal-related disorders.

Esophageal cancer is the sixth leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide [21]. The predominant types of esophageal cancers are squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) and esophageal adenocarcinoma. These carcinomas have a strong tendency to metastasise, even if the tumour is superficial [22]. In a recent histological investigation of 260 human esophageal cancers, innervation in the tumour microenvironment was identified in 38% of the cancers and, more commonly, in ESCC, while signs of PNI were detected in 12% of the samples [23]. PNI was correlated with reduced survival [23], which supports previous findings that nerve invasion by tumour cells can be used as a prognostic factor in patients with esophageal cancer [24][25]. PNI was also found to be a better prognostic indicator than lymphovascular invasion in ESCC [26].

Several neurotrophic factor receptors, including Tropomyosin receptor kinase A (TrkA) [27], TrkB [28] and p75 [27][29][30] are expressed by esophageal tumour cells. A subset of esophageal tumour cells could express both NGF and NGF receptors [27], suggesting an autocrine signalling loop. Antigenic characterization combined with the genetic tracing of peripheral glia in murine esophageal tissue revealed the presence of myelinating and non-myelinating SCs of motor processes, a network of non-myelinating perisynaptic SCs, several types of enteric glial cells, and some glial cells along the blood vessels [18]. To what extent this rich variety of cells is involved in esophageal pathology remains to be demonstrated, but p75 expression is a hallmark of activated SCs, and glia-cancer cell interaction via p75 signalling has been reported in other gastrointestinal tumours [31]. Intriguingly, a portion of ENS neurons in the esophagus are derived from SCPs that travel along the vagus nerve [32]. This contribution occurs earlier than similar SCP-borne neurogenesis in the gut [33]; nevertheless, potential subsequent contribution of SCs to esophageal homeostasis and disease remains unexplored.

3. Stomach

The stomach is innervated by extrinsic parasympathetic vagal and sympathetic spinal nerves, as well as intrinsic neurons of the ENS [34][35]. A meta-analysis of the association between PNI and survival in patients with resectable gastric cancer concluded that PNI is an independent prognostic factor and can also serve as a predictive factor for tumour recurrence [36]. Additionally, PNI might help predict patients who could benefit from postoperative adjuvant therapy [37].

The role of innervation in gastric tumour has been studied in murine models. In an earlier report, myenteric denervation in rats using benzalkonium chloride resulted in a reduced incidence of chemically induced gastric cancer [38]. Similarly, denervation by vagotomy or botulinum toxin treatment in various mouse models of gastric cancer slowed disease progression and reduced tumour lesion incidence [39]. In these tumour models, neurons act by activating Wnt signalling through the muscarinic acetylcholine receptor M3 and thus promote the expansion of gastric epithelial cells. Stomach denervation leads to diminished Wnt signalling and reduced number of Lgr5+ epithelial stem cells. Furthermore, neurons in a gastric organoid co-culture system can substitute for the presence of mandatory Wnt3a in the culture medium [39].

The activation of the Wnt pathway in stomach epithelial cells was further studied later and attributed to tuft cell- and axon-derived acetylcholine. In a positive feedback loop, Ach-activated tumour cells produce NGF and recruit more Ach-secreting axons, leading to hyperinnervation and further Wnt activation [40]. Interestingly, in a genetic mouse line, where an excess amount of NGF is secreted by gastric epithelial cells, the stromal compartment of the lamina propria is significantly expanded, epithelial tissue architecture changes, and tumours arise. Among the stromal cells, the authors observed many Nestin+/s100b+ glial cells [40]. Given the ability of glial cells to secrete neurotrophic factors, including NGF, and participate in axon guidance, it would be intriguing to study in more detail the role of these cells in gastric tumorigenesis.

4. Pancreas

4.1. Pancreatic Innervation and Insights from 3D Imaging

Innervation of the pancreas has been studied for more than a century, with important findings and descriptions dating back to the age of major discoveries in anatomy and physiology [41]. Moreover, the most evidence for the involvement of SCs in the aspects of development, physiology, and disease of the gastrointestinal system comes from the studies of this organ. The pancreas is innervated by extrinsic and intrinsic neurons. Extrinsic are mainly associated with the vagus nerve and sympathetic splanchnic nerves, as well as sensory innervation, while intrinsic stem from intrapancreatic ganglia [42][43][44]. In addition, there are connections to the ENS [42]. Nerve endings can synapse at the ganglia or directly contact other pancreatic structures, for example, blood vessels, ducts, acini, and islets [44].

Recently, several studies have addressed pancreatic innervation in more detail using advanced tissue-clearing and imaging techniques [44][45][46][47]. Quantitative imaging of the adult mouse pancreas revealed that the nerve distribution in the organ is not uniform, with a larger volume of nerve seen closer to the duodenum. Depending on the neuronal marker used, up to 35% of all islets are contacted by the axons. These islets tend to be much larger so that around half of the islets by mass are innervated. Exocrine innervation is much less dense than in the endocrine portion and, similarly, is more prevalent in the duodenal region [46]. This agrees with earlier observations from electron microscopy studies, which noted dense innervation around arterioles and islets, and rather sparse innervation around the ducts and the acini of the murine pancreas [48][49].

The anatomically compact human pancreas is very different from the diffuse mesenteric type of pancreas found in murine species [50]. Differences are also seen with respect to innervation. Unlike in the murine pancreas, the innervation density in human tissue samples is similar in the endocrine and exocrine portions, while the proportion of innervated islets is smaller than in mouse tissue [46] and nerve-endocrine contacts are sparse [51]. Interestingly, the distribution of intrapancreatic ganglia was similar in humans and mice and was not significantly affected by diabetes [46].

As expected, species differences are also observed in the way SCs are distributed within the endocrine pancreas. Most of the Insulin+ islet mass in mice is contacted by axons [46]. Additionally, direct SC− endocrine cell contacts might increase the coverage even further. SCs form a dense envelope-like coating of murine pancreatic islets with SC processes reaching inside [49][52]. In human tissue, GFAP+ cells are less dense and are associated with autonomic neurons; however, some SC projections terminate at the endocrine cells [47]. SC processes associated with thin axons were also observed in the exocrine compartment together, forming a loose network on the surface of the acinar structures [48].

4.2. Physiological Role of Innervation and SCs in Healthy Pancreas

Autonomic regulation of pancreatic function, in general, is well described [53][54]. Parasympathetic activation induces the secretion of insulin and digestive enzymes, while sympathetic signalling results in reduced secretion and blood vessel constriction. Nevertheless, a detailed examination is revealing, and new functions of innervation come to light. For example, some sympathetic nerves project to the pancreatic lymph nodes and, if stimulated, can exert immunomodulatory functions [55]. Another recent study found that sensory innervation of the vagal branch makes extensive contacts with islets and β-cells use serotonin to communicate with these neuronal processes [56]. There may be more revealing studies to come since the choice of neuronal markers can be crucial for a correct assessment of the extent of innervation [46], especially given that axons can be as thin as 0.1 μM, while some of these markers are also expressed by parenchymal cells [48].

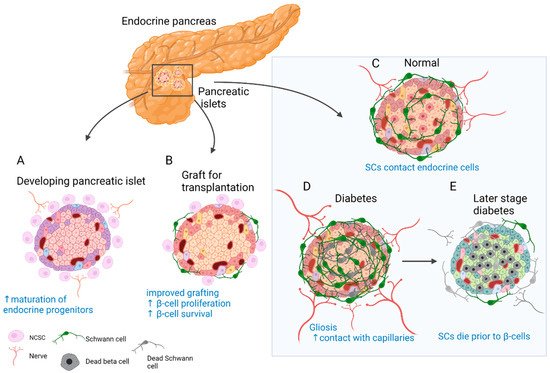

Insights from developmental studies suggest that innervation is critical for proper formation of the pancreas. Parasympathetic denervation leads to reduced β-cell proliferation in rats [57]. Disruption of sympathetic innervation and β-adrenergic signalling, on the other hand, results in hampered mouse endocrine cell maturation and altered insulin production [58]. This is reflected in the adult, since innervated islets in mice tend to be up to 10 times larger than the rest [46]. In addition, neural crest (NC) cells and glia appear to play a major role in this process. Migrating NC cells arrive in the developing murine pancreas soon after delamination and engage in reciprocal signalling with progenitors of the pancreatic epithelium to control islet mass [59]. As a result, β-cell proliferation is reduced and islet maturation is fostered (Figure 1A) [59][60]. Similarly, zebrafish NCs come into close contact with the endocrine epithelium before forming neurons that innervate the islets and pave the way for further neuronal contacts [61].

Figure 1. Role of SC and neural crest (NC) cells in the physiology and disease of the endocrine pancreas. (A) Reciprocal signalling with endocrine progenitors promotes islet maturation and glial fate choice by NC cells. (B) The transplanted islets contain surviving donor SCs. Co-transplantation and coating of endocrine islets with NC stem cell (NCSC)-like cells improve graft function and stimulate β-cell proliferation and survival. (C) SCs cover the surface of endocrine islets in mice (to a lesser extent in humans) and make contact with endocrine cells. (D) In T2D and insulitis, SCs expand and gliosis is observed. Extensive contacts are detected with capillaries. (E) With the onset of T1D SCs die before β-cells and innervation is reduced. SCs might have immunomodulatory function.

4.3. Fate and Function of SCs in Disorders of the Endocrine Pancreas

Pancreatic innervation is clearly affected by the onset of endocrine disorders (Figure 1C–E). It was reported that in models of autoimmune type 1 diabetes (T1D), such as non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice, general and sympathetic innervation is reduced [62][63]. On the contrary, other studies suggested increased innervation of surviving islets in tissue samples from both streptozotocin (STZ)-treated and NOD mouse pancreas [46][64]. Similar observations were made in human samples, and even more so, axon–endocrine cell contacts were preserved in samples from patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) [46]. The same is true for the glial counterpart of innervation. After experimental STZ treatment, which models T2D, and in early insulitis in NOD mice, reactive gliosis is observed around the islets [62][65][66]. After STZ injury, SCs demonstrate significant outgrowth and make more membrane contacts with the intra-islet capillaries [67]. With progression of insulitis, SCs die prior to β-cells [68]. One of the hypotheses suggests that peri-islet SCs could act as antigen presenters at the onset of T1D and amplify inflammatory signals [66].

The observation of glial cells surrounding the islets of Langerhans [49] and NC cells in close contact with developing endocrine cells [59] could have contributed to the idea of improving islet grafts by co-transplantation with NC stem cell (NCSC)-like cells (Figure 1B). Unlike in developmental settings in vivo, where NC cells limit endocrine cell proliferation [59][60], co-transplantation with NCSC spheres promotes adult β-cell expansion [69]. Insulin production by co-transplanted islets is also increased and can partially restore normoglycemia in mice after heterotopic transplantation [69]. Similarly, transplantation from human islets with NCSC spheres SCs mouse embryonic DRGs promotes endocrine cell proliferation, vascularisation, and innervation of the graft [70]. The same group developed a method to coat the surface of murine islets with NCSCs before transplantation. This improved engraftment into liver tissue, islet vascularisation, and overall performance of the graft. Moreover, many NCSCs migrated into the graft and differentiated to glial and neuronal phenotypes [71]. Interestingly, donor SCs are normally present in the grafted islets, and the fate of these cells was studied in optically cleared mouse islets after transplantation under the kidney capsule. SCs survive transplantation and appear to be the main contributors to the re-established SC network; however, this process is slow and does not reach the extent seen in in situ islets [72]. Along these lines, NCSCs in co-culture were able to protect insulin-producing islet cells from cytokine-induced death, suggesting a potential immune-modulatory action [73]. Taken together, SCs remain in the grafted islets, but the addition of glial cells or NCSCs could be beneficial. However, caution should be taken with such approaches, as SCs might actively participate in the immune process and exacerbate autoimmune response [66][74].

4.3. Fate and Function of SCs in Disorders of the Exocrine Pancreas

The exocrine pancreas makes up the largest portion of the organ, or about 95% by mass, and is the site of origin of various pancreatic disorders [75]. Pancreatitis, cystic fibrosis, and cancer are just a few disorders that affect the function of this tissue. Pancreatic cancer is known for its grim prognosis at the time of diagnosis and has the lowest survival rate among cancers in Europe [76].Both pancreatitis and cancer are linked to abnormal innervation. In fact, nerve size and innervation density correlate well with the severity of pancreatic disease and increase as the tissue progresses from normal to inflamed and malignant [77]. One of the common alterations that accompany such neuropathic changes is PNI, which develops in virtually all cases of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) and correlates with increased morbidity and pain [78].

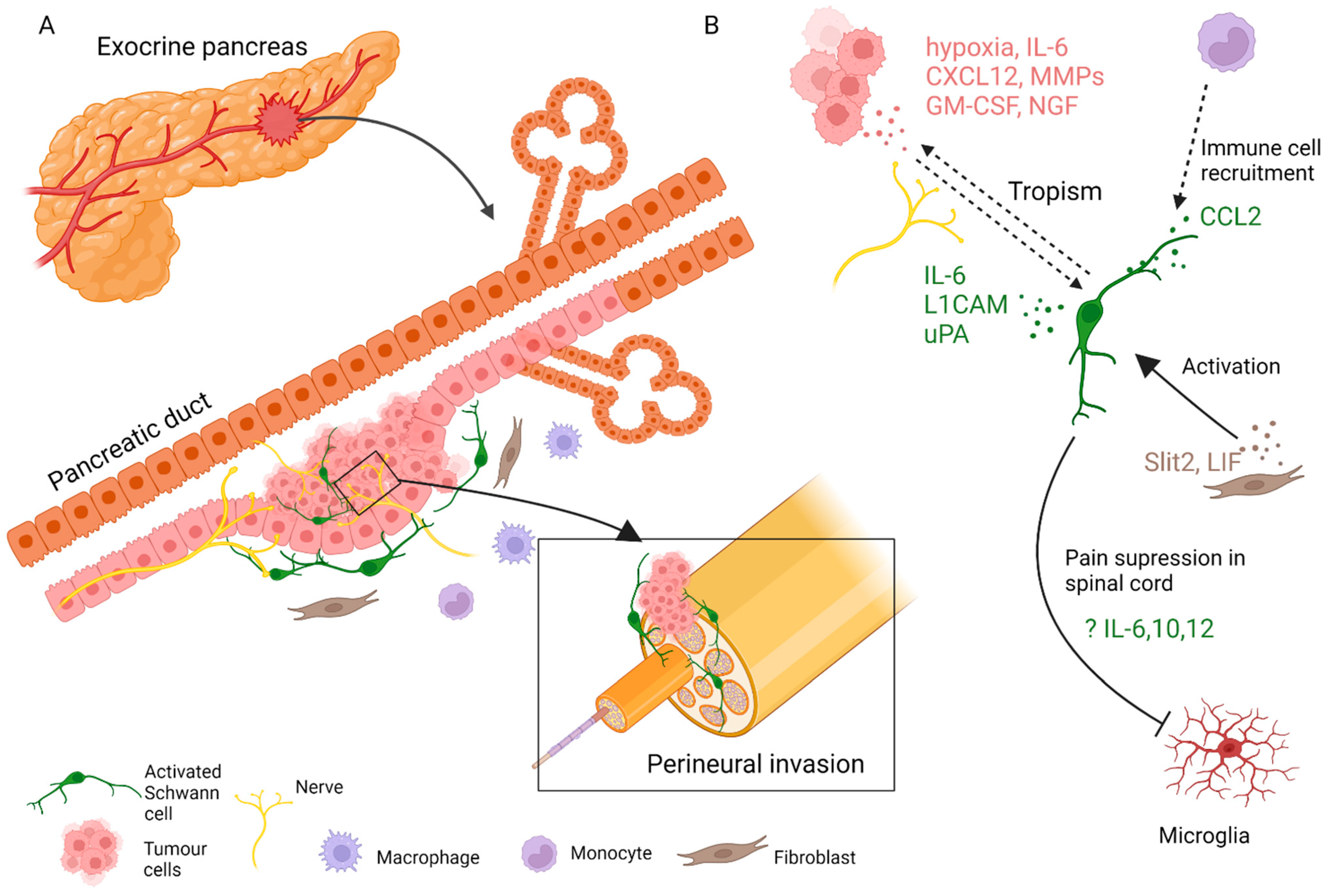

Figure 2. SC involvement in the pathophysiology of pancreatic cancer. (A) SCs, fibroblasts, immune cells, and other cells of the stroma contribute to the progression of pancreatic tumours and nerve invasion. (B) SCs engage in paracrine interaction with tumour and stromal cells.

In addition to neuron-mediated effects, other contributions of stromal cells to pancreatic neuropathy have been extensively studied. Immune cells, cancer-associated fibroblasts, and SCs have all been implicated (Figure 2) [79]. PNI in pancreatic cancer is not fully understood, but is likely driven by an initial interplay of signals from tumour and immune cells, gradually accompanied by injury response cues from various activated nerve-associated cells. An early report suggested that adenocarcinoma cells interact with SCs in PNI, as apparent from patient tissue sections [80]. Another immunohistological study of human tissue reported an activated state of intrapancreatic glia in pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer patient samples, as evidenced by increased Nestin expression [77]. Later, it was shown that SCs are localised in the vicinity of neoplastic pancreatic and colon lesions before PNI. SCs displayed tropism to pancreatic tumour cells, at least in part dependant on the NGF-p75 signalling [81]. This was a novel development and suggested that in PNI settings, nerve components could be the first to migrate. The same research team proposed that SCs are activated through various routes, notably through hypoxia, tumour-derived interleukin (IL)-6, and chemokine CXCL-12, overexpressed in the pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN) [82][83]. In this scenario, activated SCs participate in pain suppression in early PDAC lesions by modulating the activity of the astroglia and microglia of the spinal cord and could cause a delay in the diagnosis of the disease. Demir and colleagues showed that glia-specific inactivation of the CXCL-12 receptor CXCR4/CXCR7 or blockade of IL-6 signalling abrogated SC migration, decreased glial cell numbers in PanIN lesions, and increased pain sensation in mice.

SCs can be activated or participate in PDAC tumorigenesis indirectly by communicating with other cells of the stroma. For example, by producing CCL2, SCs attract CCR2-expressing monocytes that eventually differentiate to tumour macrophages and promote nerve invasion [84]. An axon guidance molecule SLIT2 derived from tumour fibroblasts modulates N-cadherin/b-catenin pathway to induce SC proliferation and migration and promote neurite outgrowth [85] Likewise, tumour stroma-derived leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) activates STAT3 signalling in SCs, leading to SC differentiation and increased neuronal remodelling in PDAC [86].

References

- Huff, T.; Daly, D.T. Neuroanatomy, Cranial Nerve 5 (Trigeminal); StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2021.

- Hargreaves, K.M. Orofacial pain. Pain 2011, 152, S25–S32.

- Rivera, C. Essentials of oral cancer. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015, 8, 11884–11894.

- Viet, C.; Schmidt, B. Biologic Mechanisms of Oral Cancer Pain and Implications for Clinical Therapy. J. Dent. Res. 2011, 91, 447–453.

- Speight, P.M.; Farthing, P.M. The pathology of oral cancer. Br. Dent. J. 2018, 225, 841–847.

- Amit, M.; Takahashi, H.; Dragomir, M.P.; Lindemann, A.; Gleber-Netto, F.O.; Pickering, C.R.; Anfossi, S.; Osman, A.A.; Cai, Y.; Wang, R.; et al. Loss of p53 drives neuron reprogramming in head and neck cancer. Nature 2020, 578, 449–454.

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, M.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X.; Ji, T. The neuropeptide calcitonin gene-related peptide links perineural invasion with lymph node metastasis in oral squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 1–10.

- Chiang, C.-Y.; Dostrovsky, J.O.; Iwata, K.; Sessle, B.J. Role of Glia in Orofacial Pain. Neuroscientist 2011, 17, 303–320.

- Ye, Y.; Salvo, E.; Romero-Reyes, M.; Akerman, S.; Shimizu, E.; Kobayashi, Y.; Michot, B.; Gibbs, J. Glia and Orofacial Pain: Progress and Future Directions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5345.

- Salvo, E.; Saraithong, P.; Curtin, J.G.; Janal, M.N.; Ye, Y. Reciprocal interactions between cancer and Schwann cells contribute to oral cancer progression and pain. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01223.

- Salvo, E.; Tu, N.H.; Scheff, N.N.; Dubeykovskaya, Z.A.; Chavan, S.A.; Aouizerat, B.E.; Ye, Y. TNFα promotes oral cancer growth, pain, and Schwann cell activation. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1840.

- Shan, C.; Wei, J.; Hou, R.; Wu, B.; Yang, Z.; Wang, L.; Lei, D.; Yang, X. Schwann cells promote EMT and the Schwann-like differentiation of salivary adenoid cystic carcinoma cells via the BDNF/TrkB axis. Oncol. Rep. 2015, 35, 427–435.

- Ein, L.; Mei, C.; Bracho, O.; Bas, E.; Monje, P.; Weed, D.; Sargi, Z.; Thomas, G.; Dinh, C. Modulation of BDNF–TRKB Interactions on Schwann Cell-induced Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Dispersion In Vitro. Anticancer Res. 2019, 39, 5933–5942.

- Kaukua, N.; Shahidi, M.K.; Konstantinidou, C.; Dyachuk, V.; Kaucka, M.; Furlan, A.; An, Z.; Wang, L.; Hultman, I.; Ährlund-Richter, L.; et al. Glial origin of mesenchymal stem cells in a tooth model system. Nature 2014, 513, 551–554.

- Martyn, G.V.; Shurin, G.V.; Keskinov, A.A.; Bunimovich, Y.L.; Shurin, M.R. Schwann cells shape the neuro-immune environs and control cancer progression. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2019, 68, 1819–1829.

- Couve, E.; Schmachtenberg, O. Schwann Cell Responses and Plasticity in Different Dental Pulp Scenarios. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 299.

- Neuhuber, W.L.; Wörl, J. Enteric co-innervation of striated muscle in the esophagus: Still enigmatic? Histochem. Cell Biol. 2016, 146, 721–735.

- Kapitza, C.; Chunder, R.; Scheller, A.; Given, K.; Macklin, W.; Enders, M.; Kuerten, S.; Neuhuber, W.; Wörl, J. Murine Esophagus Expresses Glial-Derived Central Nervous System Antigens. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3233.

- Nikaki, K.; Sawada, A.; Ustaoglu, A.; Sifrim, D. Neuronal Control of Esophageal Peristalsis and Its Role in Esophageal Disease. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2019, 21, 59.

- Farmer, A.D.; Ruffle, J.K.; Aziz, Q. The Role of Esophageal Hypersensitivity in Functional Esophageal Disorders. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2017, 51, 91–99.

- Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Dikshit, R.; Eser, S.; Mathers, C.; Rebelo, M.; Parkin, D.M.; Forman, D.; Bray, F. Cancer Incidence and Mortality Worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 136, E359–E386.

- Pennathur, A.; Gibson, M.K.; Jobe, B.A.; Luketich, J.D. Oesophageal carcinoma. Lancet 2013, 381, 400–412.

- Griffin, N.; Rowe, C.W.; Gao, F.; Jobling, P.; Wills, V.; Walker, M.M.; Faulkner, S.; Hondermarck, H. Clinicopathological Significance of Nerves in Esophageal Cancer. Am. J. Pathol. 2020, 190, 1921–1930.

- Chen, J.-W.; Xie, J.-D.; Ling, Y.-H.; Li, P.; Yan, S.-M.; Xi, S.-Y.; Luo, R.-Z.; Yun, J.-P.; Xie, D.; Cai, M.-Y. The prognostic effect of perineural invasion in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 313.

- Xu, G.; Feng, F.; Liu, Z.; Liu, S.; Zheng, G.; Xiao, S.; Cai, L.; Yang, X.; Li, G.; Lian, X.; et al. Prognosis and Progression of ESCC Patients with Perineural Invasion. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 43828.

- Guo, Y.-N.; Tian, D.-P.; Gong, Q.-Y.; Huang, H.; Yang, P.; Chen, S.-B.; Billan, S.; He, J.-Y.; Huang, H.-H.; Xiong, P.; et al. Perineural Invasion is a Better Prognostic Indicator than Lymphovascular Invasion and a Potential Adjuvant Therapy Indicator for pN0M0 Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 27, 4371–4381.

- Tsunoda, S.; Okumura, T.; Ito, T.; Mori, Y.; Soma, T.; Watanabe, G.; Kaganoi, J.; Itami, A.; Sakai, Y.; Shimada, Y. Significance of nerve growth factor overexpression and its autocrine loop in oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Br. J. Cancer 2006, 95, 322–330.

- Zhou, Y.; Sinha, S.; Schwartz, J.L.; Adami, G.R. A subtype of oral, laryngeal, esophageal, and lung, squamous cell carcinoma with high levels of TrkB-T1 neurotrophin receptor mRNA. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 1–12.

- Huang, S.-D.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, X.-H.; Gong, D.-J.; Bai, C.-G.; Wang, F.; Luo, J.-H.; Xu, Z.-Y. Self-renewal and chemotherapy resistance of p75NTR positive cells in esophageal squamous cell carcinomas. BMC Cancer 2009, 9, 9.

- Yamaguchi, T.; Okumura, T.; Hirano, K.; Watanabe, T.; Nagata, T.; Shimada, Y.; Tsukada, K. p75 neurotrophin receptor expression is a characteristic of the mitotically quiescent cancer stem cell population present in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int. J. Oncol. 2016, 48, 1943–1954.

- Demir, I.E.; Boldis, A.; Pfitzinger, P.L.; Teller, S.; Brunner, E.; Klose, N.; Kehl, T.; Maak, M.; Lesina, M.; Laschinger, M.; et al. Investigation of Schwann Cells at Neoplastic Cell Sites Before the Onset of Cancer Invasion. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2014, 106, dju184.

- Espinosa-Medina, I.; Jevans, B.; Boismoreau, F.; Chettouh, Z.; Enomoto, H.; Müller, T.; Birchmeier, C.; Burns, A.J.; Brunet, J.-F. Dual origin of enteric neurons in vagal Schwann cell precursors and the sympathetic neural crest. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 11980–11985.

- Uesaka, T.; Nagashimada, M.; Enomoto, H. Neuronal Differentiation in Schwann Cell Lineage Underlies Postnatal Neurogenesis in the Enteric Nervous System. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 9879–9888.

- Chaudhry, S.R.; Liman, M.N.P.; Peterson, D.C. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Stomach; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2021.

- Phillips, R.J.; Powley, T.L. Innervation of the gastrointestinal tract: Patterns of aging. Auton. Neurosci. 2007, 136, 1–19.

- Deng, J.; You, Q.; Gao, Y.; Yu, Q.; Zhao, P.; Zheng, Y.; Fang, W.; Xu, N.; Teng, L. Prognostic Value of Perineural Invasion in Gastric Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e88907.

- Tao, Q.; Zhu, W.; Zhao, X.; Li, M.; Shu, Y.; Wang, D.; Li, X. Perineural Invasion and Postoperative Adjuvant Chemotherapy Efficacy in Patients with Gastric Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 530.

- Polli-Lopes, A.C.; Zucoloto, S.; Cunha, F.D.Q.; Figueiredo, L.A.D.S.; Garcia, S.B. Myenteric denervation reduces the incidence of gastric tumors in rats. Cancer Lett. 2003, 190, 45–50.

- Zhao, C.-M.; Hayakawa, Y.; Kodama, Y.; Muthupalani, S.; Westphalen, C.B.; Andersen, G.T.; Flatberg, A.; Johannessen, H.; Friedman, R.A.; Renz, B.W.; et al. Denervation suppresses gastric tumorigenesis. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 250ra115.

- Hayakawa, Y.; Sakitani, K.; Konishi, M.; Asfaha, S.; Niikura, R.; Tomita, H.; Renz, B.W.; Tailor, Y.; Macchini, M.; Middelhoff, M.; et al. Nerve Growth Factor Promotes Gastric Tumorigenesis through Aberrant Cholinergic Signaling. Cancer Cell 2016, 31, 21–34.

- Langerhans, P.; Morrison, H. Contributions to the Microscopic Anatomy of the Pancreas; Bulletin of the Institute of the History of Medicine, The Johns Hopkins University Press: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1937; Volume 5, pp. 259–297.

- Li, W.; Yu, G.; Liu, Y.; Sha, L. Intrapancreatic Ganglia and Neural Regulation of Pancreatic Endocrine Secretion. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 21.

- Babic, T.; Travagli, R.A. Neural Control of the Pancreas; APA: Prairie Village, KS, USA, 2016.

- Makhmutova, M.; Caicedo, A. Optical Imaging of Pancreatic Innervation. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 445.

- Chien, H.-J.; Chiang, T.-C.; Peng, S.-J.; Chung, M.-H.; Chou, Y.-H.; Lee, C.-Y.; Jeng, Y.-M.; Tien, Y.-W.; Tang, S.-C. Human pancreatic afferent and efferent nerves: Mapping and 3-D illustration of exocrine, endocrine, and adipose innervation. Am. J. Physiol. Liver Physiol. 2019, 317, G694–G706.

- Alvarsson, A.; Jimenez-Gonzalez, M.; Li, R.; Rosselot, C.; Tzavaras, N.; Wu, Z.; Stewart, A.F.; Garcia-Ocaña, A.; Stanley, S.A. A 3D atlas of the dynamic and regional variation of pancreatic innervation in diabetes. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaaz9124.

- Campbell-Thompson, M.; Tang, S.-C. Pancreas Optical Clearing and 3-D Microscopy in Health and Diabetes. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 644826.

- Ushiki, T.; Watanabe, S. Distribution and ultrastructure of the autonomic nerves in the mouse pancreas. Microsc. Res. Tech. 1997, 37, 399–406.

- Sunami, E.; Kanazawa, H.; Hashizume, H.; Takeda, M.; Hatakeyama, K.; Ushiki, T. Morphological Characteristics of Schwann Cells in the Islets of Langerhans of the Murine Pancreas. Arch. Histol. Cytol. 2001, 64, 191–201.

- Tsuchitani, M.; Sato, J.; Kokoshima, H. A comparison of the anatomical structure of the pancreas in experimental animals. J. Toxicol. Pathol. 2016, 29, 147–154.

- Rodriguez-Diaz, R.; Abdulreda, M.H.; Formoso, A.L.; Gans, I.; Ricordi, C.; Berggren, P.-O.; Caicedo, A. Innervation Patterns of Autonomic Axons in the Human Endocrine Pancreas. Cell Metab. 2011, 14, 45–54.

- Donev, S. Ultrastructural evidence for the presence of a glial sheath investing the islets of Langerhans in the pancreas of mammals. Cell Tissue Res. 1984, 237, 343–348.

- Love, J.A.; Yi, E.; Smith, T.G. Autonomic pathways regulating pancreatic exocrine secretion. Auton. Neurosci. 2007, 133, 19–34.

- Rodriguez-Diaz, R.; Caicedo, A. Neural control of the endocrine pancreas. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 28, 745–756.

- Guyot, M.; Simon, T.; Ceppo, F.; Panzolini, C.; Guyon, A.; Lavergne, J.; Murris, E.; Daoudlarian, D.; Brusini, R.; Zarif, H.; et al. Pancreatic nerve electrostimulation inhibits recent-onset autoimmune diabetes. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 1446–1451.

- Makhmutova, M.; Weitz, J.; Tamayo, A.; Pereira, E.; Boulina, M.; Almaça, J.; Rodriguez-Diaz, R.; Caicedo, A. Pancreatic β-Cells Communicate with Vagal Sensory Neurons. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 875–888.e11.

- Lausier, J.; Diaz, W.C.; Roskens, V.; LaRock, K.; Herzer, K.; Fong, C.G.; Latour, M.G.; Peshavaria, M.; Jetton, T.L. Vagal control of pancreatic β-cell proliferation. Am. J. Physiol. Metab. 2010, 299, E786–E793.

- Borden, P.; Houtz, J.; Leach, S.D.; Kuruvilla, R. Sympathetic Innervation during Development Is Necessary for Pancreatic Islet Architecture and Functional Maturation. Cell Rep. 2013, 4, 287–301.

- Nekrep, N.; Wang, J.; Miyatsuka, T.; German, M.S. Signals from the neural crest regulate beta-cell mass in the pancreas. Development 2008, 135, 2151–2160.

- Plank, J.L.; Mundell, N.A.; Frist, A.Y.; LeGrone, A.W.; Kim, T.; Musser, M.A.; Walter, T.J.; Labosky, P.A. Influence and timing of arrival of murine neural crest on pancreatic beta cell development and maturation. Dev. Biol. 2011, 349, 321–330.

- Yang, Y.H.C.; Kawakami, K.; Stainier, D.Y. A new mode of pancreatic islet innervation revealed by live imaging in zebrafish. eLife 2018, 7, e34519.

- Persson-Sjögren, S.; Holmberg, D.; Forsgren, S. Remodeling of the innervation of pancreatic islets accompanies insulitis preceding onset of diabetes in the NOD mouse. J. Neuroimmunol. 2005, 158, 128–137.

- Taborsky, G.J., Jr.; Mei, Q.; Hackney, D.J.; Figlewicz, D.P.; Leboeuf, R.; Mundinger, T.O. Loss of islet sympathetic nerves and impairment of glucagon secretion in the NOD mouse: Relationship to invasive insulitis. Diabetologia 2009, 52, 2602–2611.

- Chiu, Y.-C.; Hua, T.-E.; Fu, Y.-Y.; Pasricha, P.J.; Tang, S.-C. 3-D imaging and illustration of the perfusive mouse islet sympathetic innervation and its remodelling in injury. Diabetologia 2012, 55, 3252–3261.

- Teitelman, G.; Guz, Y.; Ivkovic, S.; Ehrlich, M. Islet injury induces neurotrophin expression in pancreatic cells and reactive gliosis of peri-islet Schwann cells. J. Neurobiol. 1998, 34, 304–318.

- Tang, S.-C.; Chiu, Y.-C.; Hsu, C.-T.; Peng, S.-J.; Fu, Y.-Y. Plasticity of Schwann cells and pericytes in response to islet injury in mice. Diabetologia 2013, 56, 2424–2434.

- Tang, S.-C.; Peng, S.-J.; Chien, H.-J. Imaging of the islet neural network. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2014, 16, 77–86.

- Winer, S.; Tsui, H.; Lau, A.; Song, A.; Li, X.; Cheung, R.K.; Sampson, A.; Afifiyan, F.; Elford, A.; Jackowski, G.; et al. Autoimmune islet destruction in spontaneous type 1 diabetes is not β-cell exclusive. Nat. Med. 2003, 9, 198–205.

- Olerud, J.; Kanaykina, N.; Vasilovska, S.; King, D.; Sandberg, M.; Jansson, L.; Kozlova, E.N. Neural crest stem cells increase beta cell proliferation and improve islet function in co-transplanted murine pancreatic islets. Diabetologia 2009, 52, 2594–2601.

- Grapensparr, L.; Vasylovska, S.; Li, Z.; Olerud, J.; Jansson, L.; Kozlova, E.; Carlsson, P.-O. Co-transplantation of Human Pancreatic Islets with Post-migratory Neural Crest Stem Cells Increases β-Cell Proliferation and Vascular and Neural Regrowth. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 100, E583–E590.

- Lau, J.; Vasylovska, S.; Kozlova, E.; Carlsson, P.-O. Surface Coating of Pancreatic Islets with Neural Crest Stem Cells Improves Engraftment and Function after Intraportal Transplantation. Cell Transplant. 2015, 24, 2263–2272.

- Juang, J.-H.; Kuo, C.-H.; Peng, S.-J.; Tang, S.-C. 3-D Imaging Reveals Participation of Donor Islet Schwann Cells and Pericytes in Islet Transplantation and Graft Neurovascular Regeneration. eBioMedicine 2015, 2, 109–119.

- Ngamjariyawat, A.; Turpaev, K.; Vasylovska, S.; Kozlova, E.N.; Welsh, N. Co-Culture of Neural Crest Stem Cells (NCSC) and Insulin Producing Beta-TC6 Cells Results in Cadherin Junctions and Protection against Cytokine-Induced Beta-Cell Death. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e61828.

- Yantha, J.; Tsui, H.; Winer, S.; Song, A.; Wu, P.; Paltser, G.; Ellis, J.; Dosch, H.-M. Unexpected Acceleration of Type 1 Diabetes by Transgenic Expression of B7-H1 in NOD Mouse Peri-Islet Glia. Diabetes 2010, 59, 2588–2596.

- Daniel S. Longnecker; Anatomy and Histology of the Pancreas. The Pancreapedia: Exocrine Pancreas Knowledge Base 2014, NA, NA, 10.3998/panc.2014.3.

- Roberta De Angelis; Milena Sant; Michel Coleman; Silvia Francisci; Paolo Baili; Daniela Pierannunzio; Annalisa Trama; Otto Visser; Hermann Brenner; Eva Ardanaz; et al.Magdalena Bielska-LasotaGerda EngholmAlice NenneckeSabine SieslingFranco BerrinoRiccardo Capocaccia Cancer survival in Europe 1999–2007 by country and age: results of EUROCARE-5—a population-based study. The Lancet Oncology 2014, 15, 23-34, 10.1016/s1470-2045(13)70546-1.

- Güralp Onur Ceyhan; Ihsan Ekin Demir; Ulrich Rauch; Frank Bergmann; Michael W Müller; Markus W Büchler; Helmut Friess; Karl-Herbert Schäfer; Pancreatic Neuropathy Results in “Neural Remodeling” and Altered Pancreatic Innervation in Chronic Pancreatitis and Pancreatic Cancer. American Journal of Gastroenterology 2009, 104, 2555-2565, 10.1038/ajg.2009.380.

- Stephan Schorn; Ihsan Ekin Demir; Bernhard Haller; Florian Scheufele; Carmen Mota Reyes; Elke Tieftrunk; Mine Sargut; Ruediger Goess; Helmut Friess; Güralp Onur Ceyhan; et al. The influence of neural invasion on survival and tumor recurrence in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma – A systematic review and meta-analysis. Surgical Oncology 2017, 26, 105-115, 10.1016/j.suronc.2017.01.007.

- Elisabeth Hessmann; Soeren M. Buchholz; Ihsan Ekin Demir; Shiv K. Singh; Thomas M. Gress; Volker Ellenrieder; Albrecht Neesse; Microenvironmental Determinants of Pancreatic Cancer. Physiological Reviews 2020, 100, 1707-1751, 10.1152/physrev.00042.2019.

- Dale E. Bockman; Markus Büchler; Hans G. Beger; Interaction of pancreatic ductal carcinoma with nerves leads to nerve damage. Gastroenterology 1994, 107, 219-230, 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90080-9.

- Ihsan Ekin Demir; Alexandra Boldis; Paulo L. Pfitzinger; Steffen Teller; Eva Brunner; Natascha Klose; Timo Kehl; Matthias Maak; Marina Lesina; Melanie Laschinger; et al.Klaus-Peter JanssenHana AlgülHelmut FriessGüralp O. Ceyhan Investigation of Schwann Cells at Neoplastic Cell Sites Before the Onset of Cancer Invasion. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2014, 106, NA, 10.1093/jnci/dju184.

- Ihsan Ekin Demir; Elke Tieftrunk; Stephan Schorn; Ömer Cemil Saricaoglu; Paulo L Pfitzinger; Steffen Teller; Kun Wang; Christine Waldbaur; Magdalena U Kurkowski; Sonja Maria Wörmann; et al.Victoria ShawTimo KehlMelanie LaschingerEithne CostelloHana AlgülHelmut FriessGüralp O Ceyhan Activated Schwann cells in pancreatic cancer are linked to analgesia via suppression of spinal astroglia and microglia. Gut 2016, 65, 1001-1014, 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309784.

- Ihsan Ekin Demir; Kristina Kujundzic; Paulo L. Pfitzinger; Ömer Cemil Saricaoglu; Steffen Teller; Timo Kehl; Carmen Mota Reyes; Linda S. Ertl; Zhenhua Miao; Thomas J. Schall; et al.Elke TieftrunkBernhard HallerKalliope Nina DiakopoulosMagdalena U. KurkowskiMarina LesinaAchim KrügerHana AlgülHelmut FriessGüralp O. Ceyhan Early pancreatic cancer lesions suppress pain through CXCL12-mediated chemoattraction of Schwann cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2016, 114, 201606909-E94, 10.1073/pnas.1606909114.

- Bakst, R.L.; Xiong, H.; Chen, C.-H.; Deborde, S.; Lyubchik, A.; Zhou, Y.; He, S.; McNamara, W.; Lee, S.-Y.; Olson, O.; et al. Inflammatory Monocytes Promote Perineural Invasion via CCL2-Mediated Recruitment and Cathepsin B Expression. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 6400–6414.

- Secq, V.; Leca, J.F.; Bressy, C.; Guillaumond, F.; Skrobuk, P.; Nigri, J.; Lac, S.; Lavaut, M.-N.; Bui, T.-T.; Thakur, A.K.; et al. Stromal SLIT2 impacts on pancreatic cancer-associated neural remodeling. Cell Death Dis. 2015, 6, e1592.

- Bressy, C.; Lac, S.; Nigri, J.; Leca, J.; Roques, J.; Lavaut, M.-N.; Secq, V.; Guillaumond, F.; Bui, T.-T.; Pietrasz, D.; et al. LIF Drives Neural Remodeling in Pancreatic Cancer and Offers a New Candidate Biomarker. Cancer Res. 2017, 78, 909–921.

More