Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Fatima Jamil and Version 2 by Conner Chen.

The rhizosphere serves as a hotspot for diverse microbial activity. It is an intricate ecosystem comprising nutrient-rich soil that surrounds the plant roots, which provides a pool for plant–microbe communication. The term “Rhizomicrobiome” is defined as a microbial community that is present in the rhizosphere [29]. A variety of microorganisms reside within the rhizosphere, including bacteria, fungi, nematodes, protists, and invertebrates [11]. Most of the microbiome studies within the context of rhizosphere signaling have been focused on the bacteria and fungi that make up the major portion of the rhizosphere microbiome.

- rhizosphere

- microbial metabolites

- plant–microbe signaling

- holobiont

- plant-microbe communications

- rhizomicrobiome

- quorum-sensing

1. Rhizosphere: A Pool of Plant–Microbe Signaling

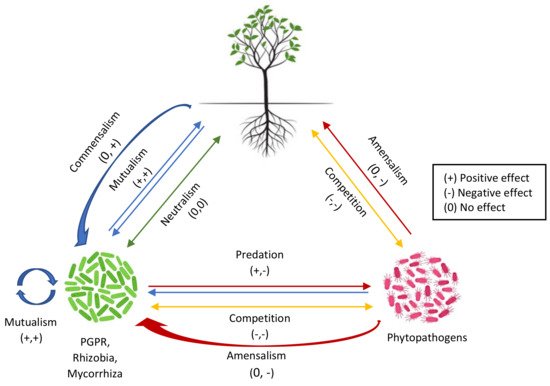

The rhizosphere serves as a hotspot for diverse microbial activity. It is an intricate ecosystem comprising nutrient-rich soil that surrounds the plant roots, which provides a pool for plant–microbe communication. The term “Rhizomicrobiome” is defined as a microbial community that is present in the rhizosphere [1][29]. A variety of microorganisms reside within the rhizosphere, including bacteria, fungi, nematodes, protists, and invertebrates [2][11]. Most of the microbiome studies within the context of rhizosphere signaling have been focused on the bacteria and fungi that make up the major portion of the rhizosphere microbiome. However, viruses that infect bacteria, which are known as phages, have an influence on the dynamics of the rhizosphere microbiome. The most abundant known phages in the soil virome include Microviridae, Siphoviridae, and Podoviridae [3][30]. The diversity and amount of identified viruses in the rhizosphere is much less, i.e., 2700 less than bacterial abundance, which amounts to around 1010 species per g of soil [4][5][31,32]. The complete biological entity comprising a plant and its associated microbial community, i.e., the symbionts (facultative and obligate) and microbes that have parasitic relationships with the host plant, is referred to as a “holobiont” [6][33]. The cascade of intricate chemical signals develops a communication within the rhizosphere that facilitates various mechanisms in a holobiont, i.e., root–root interactions, biofilm formation, nutrient acquisition, microbiota development, and resistance against pathogens [7][8][9][34,35,36]. Different types of interactions between microbes and plants are depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of interactions between rhizo-microorganisms and plants.

According to the “rhizosphere effect”, this region is associated with a lesser microbial diversity but a higher bacterial abundance compared to bulk soil [10][37]. The recruitment of microbes within the rhizosphere directly depends on the soil properties, soil type, and plant metabolites [11][38]. Different plant genotypes and physicochemical soil properties develop specific environments for the selection of a promising microbiome [7][12][10,34]. Plant-derived metabolites or root exudates play a significant role in the shaping of the rhizomicrobiome by modifying the soil chemistry around the plant roots and serving as substrates for the growth of specific microbiota [13][39]. The root exudates differ both in quality and quantity depending on the type, nutritional status, and growth stage of the plant [14][40]. These root exudates, including both primary and secondary metabolites, contain 10–16% of the total plant nitrogen and 11% of the photosynthetically fixed carbon that actively tunes the microbiota in the microbial reservoir that is within the vicinity of the plant roots [15][41]. Another factor that affects the rhizomicrobiome is the cellular response that is shown either by the microbes or the plants, which results in transformation, catabolism, and resistance to the chemical that is being sensed [2][11]. The release of root exudates into the rhizosphere by plants selects the desired microbial community by attracting it while deterring harmful communities, which in turn allows plants to be adaptable. This selection process for microbiota is known as “niche colonization” [16][17][42,43].

Signaling in the rhizosphere can be categorized into two major types based on the direction of the communication, i.e., the inter-and intraspecies microbial signaling and the interkingdom signaling between microbes and plants.

2. Inter- or Intraspecies Signaling among Microorganisms

Microbes in the rhizomicrobiome interact with each other by producing signaling molecules that adjust their gene expression [2][11]. Inter- or intraspecies communication among microbes occurs via the quorum sensing mechanism, which involves cell density-dependent coordination. Quorum sensing (QS) is the cell-to-cell signaling process that takes place through the synthesis, release, and detection of chemical signals [18][19][44,45]. These chemical signals are also known as autoinducers (AIs) and they regulate the gene expression of some bacterial functions upon the recognition of the signal by the recipient, i.e., biofilm formation, adhesion, motility [20][21][22][46,47,48], propagation, virulence, metabolism [23][49], and symbiotic association [24][1].

Quorum sensing signals in bacteria are categorized into two groups: acyl-homoserine lactone (AHLs or AI-1), which is found in Gram-negative bacteria, and autoinducer peptides (AIPs), which are found in Gram-positive bacteria; and autoinducer type 2 (AI-2), which has the traits of both AHLs and AIPs and is found in both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria [25][26][50,51]. N-acyl homoserine lactone (N-AHL) has been majorly reported in various Gram-negative bacteria, including Burkholderia sp., Pseudomonas syringae, Pseudomonas putida, Pseudomonas chlororaphis, Erwinia sp., and Serratia sp. (Table 1) [27][28][52,53]. As well as AHLs, a diverse range of signals have been reported in Gram-negative bacteria, i.e., fatty acid methyl esters, 2-alkyl-quinolones, furanone, and γ-butyrolactones [25][29][30][16,50,54].

Table 1. Characterization of quorum sensing signaling molecules that are produced by different rhizomicrobes with respect to the type of communication within the rhizosphere.

| Type of Microbe | Rhizo-Microorganisms | Quorum Sensing Molecules | Type of Communication | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gram-positive bacteria | Bacillus subtilis | ComX pheromone | Inter- and intraspecies | [31][6] |

| Streptomyces spp. | Gamma-butyrolactones (A-factor) and methylenomycin furans (MMF1) | Interspecies | [32][55] | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Circular oligopeptide | Interspecies | [29][16] | |

| Stenotrophomonas chelatiphaga | DSF (diffuse signal factor) | Interkingdom (poplar plant) | [33][56] | |

| Bacillus velezensis | AI-2 synthetase (2-methyl-2,3,3,4-tetrahydroxytetrahydrofuran (THMF)) | Interkingdom (maize plant) | [34][57] | |

| Gram-negative bacteria | Burkholderia sp. | N-3-oxo-hexanoyl-homoserine lactone (3OC6-HSL) | Interkingdom (wheat and arabidopsis plant) | [35][58] |

| Serratia glossinae | N-hexanoyl-L-homoserine lactone (m/z 200) and N-octanoyl-L-homoserine lactone (m/z 228) | Interkingdom (rice plant) |

[36][59] | |

| Serratia plymuthica | N-butanoyl-HSL, N-hexanoyl-HSL, and N-3-oxo-hexanoyl-HSL (OHHL) | Interkingdom (oil seed rape) | [37][60] | |

| Burkholderia graminis M12 and B. graminis M14 | N-(3-oxododecanoyl)-L-homoserine lactone (3-oxo-C12-HSL or OC12-HSL (where “O” indicates an oxo substitution at the third carbon atom)) and 3-oxo-C14-HSL (OC14-HSL) | Interkingdom (tomato plant) | [38][61] | |

| Serratia marcescens | N-3-oxo-hexanoyl-homoserine lactone (3OC6-HSL) | Intraspecies and interkingdom (tobacco plant) | [39][62] | |

| Burkholderia sp. and Pseudomonas sp. | N-butyryl-homoserine lactone (C4-HSL) | Interkingdom (arabidopsis plant) | [40][63] | |

| Ochrobactrum sp. | 3O-C7-HSL and 3OH-C7-HSL | Interkingdom (bean plant) | [41][64] | |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | DSF (diffuse signal factor) | Interkingdom (oil seed rape) | [42][65] | |

| Serratia glossinae | N-octanoyl-L-homoserine lactone and N-hexanoyl-L-homoserine lactone | Interkingdom (sesame plant) | [36][59] | |

| Fungi | Candida albicans | Tyrosol, γ-butyrolactone, and farnesol | Intraspecies | [43][66] |

Another type of QS bacterial signals is antibiotics, which have been reported for intra- or interspecies communication [44][67]. A recent study revealed some antibiotic signals in a bacterial strain that resided in the tobacco rhizosphere, Lysobacter capsica. The strain possessed biocontrol potential due to its production of antifungal and antibiotic signals, i.e., cyclic lipodepsipeptides and cyclic and polycyclic tetramate macrolactams [45][68]. Fungi also produce quorum sensing signals that communicate with bacterial species, e.g., γ-heptalactone, tyrosol, γ-butyrolactone, dodecanol, and farnesol [46][69]. Fungal and bacterial interaction through QS signals creates a competition for existence among the associated microbes in the rhizosphere in terms of infecting the host [47][70].

Another important class of signaling molecules is volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Microbial VOCs are synthesized and released for long-distance communication among a microbial community and also in microbe–plant interaction [48][71]. VOCs are low molecular weight lipophilic compounds (100–500 Da) that are produced by various bacterial and fungal species through distinct metabolic pathways that are specific to the species genotype [49][72]. The VOCs of bacterial origin include alkanes, ketones, alkene, terpenoids, and sulfurs [50][51][73,74]. VOCs play an important role in microbe–microbe communication by serving as antimicrobial QS signaling molecules and influencing microbial activity, i.e., virulence, stress resistance, and biofilm formation [52][53][75,76]. These attributes are exemplified as a low concentration of nitric oxide (NO) influences the biofilm formation in bacterial species such as P. aeruginosa, B. licheniformis, and S. marcescens [54][77]. Apart from this, VOC signals have been reported to regulate plant growth (root architecture and hormonal signaling) and plant immunity against biotic and abiotic stresses [48][71]. Additional studies will further unravel other signaling mechanisms that are associated with microbial VOCs.

Hence, these intricate signaling mechanisms among rhizospheric microorganisms have a key role in the shaping of the rhizomicrobiome by recruiting specific microbes through inter- or intraspecies communication.

3. Interkingdom Signaling

Microbes and plants interact with each other via interkingdom signaling, which can influence plant growth by either inducing or suppressing gene expression. Interkingdom signaling can be subdivided into two categories based on the stimulus direction: microbe–plant signaling and plant–microbe signaling.

3.1. Microbe–Plant Signaling

In microbe–plant signaling, microbes produce and emit signals that induce symbiotic interactions with the plant. Microbial signals that are of rhizosphere origin can trigger definite changes in the plant transcriptome. As in plants, phytohormones are also produced by PGPR. These plant growth-stimulating signals can regulate the developmental processes of plants and can also provide plants with resistance to abiotic and biotic stresses. Many PGPRs, including Azospirillum spp., Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, B. muralis, B. thuringiensis, Rhizobium spp., and Pseudomonas spp., have been reported to produce a diverse group of phytohormones, e.g., auxin, abscisic acid, salicylic acid, cytokinin, gibberellin, and strigolactones [55][56][57][58][78,79,80,81]. A recent study in Nature reported three newly isolated strains of Phoma spp. in the rhizosphere of Pinus tabulaeformis. These strains secreted stress the resistance substance abscisic acid (ABA) when under drought stress, which triggered drought resistance mechanisms in the pine tree and also stimulated its antioxidant activities [59][82].

Most of the literature on microbe–plant communication has been focused on beneficial interactions, such as the induction of plant growth and plant defenses against biotic and abiotic stresses. Rhizospheric microbes that have plant-friendly associations include mycorrhiza, rhizobia, plant growth-promoting bacteria, and fungi (PGPR or PGPF) [2][11]. Microbial signals are recognized by plants as microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs), i.e., flagellin, chitin, and lipopolysaccharides, via pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that trigger a local defense through a hormonal signaling network, which in turn produces immune responses [60][61][62][83,84,85].

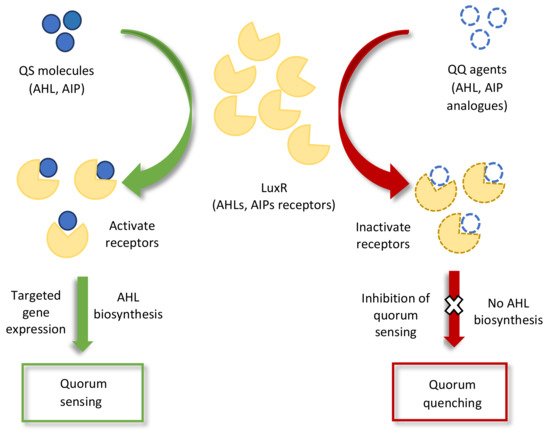

Quorum sensing signals have also been reported in interkingdom communication. Bacterial QS signals that are perceived by plants elicit various plant responses, e.g., AHLs (N-butanoyl homoserine lactone and N-hexanoyl homoserine lactone), which aid in the development of symbiotic association with plants and enhance root growth by modifying the hormonal levels in the plant [20][63][46,86]. Another bacterial QS molecule, DSF, stimulates innate immunity (the detection of harmful microbes via PRRs) in different plants [64][87]. Some other examples of QS sensing in interkingdom communication is presented in Table 1. As well as causing physiological changes in plants, bacterial QS molecules also provoke the plants into secreting molecules that mimic the QS molecules of pathogenic microbes [65][66][88,89]. For example, the p-coumaric acid that is produced by garlic [67][90], the isothiocyanate sulforaphane that is produced by broccoli [68][91], the curcumin that is produced by turmeric [69][92], and the patulin that is produced by fruits (apple, banana, pear, grape, etc.) [70][93]. Studies on AHL mimicry have shown that the mimicry molecule of bacterial AHL (AHL analog) specifically interferes with QS regulatory pathways and can either stimulate or inhibit the gene expression of the original QS receptor or host, as illustrated in Figure 2 [71][72][94,95]. This type of interference in microbial QS signaling for attenuating pathogenicity is known as quorum quenching (QQ) [18][73][74][44,96,97]. A recent study identified a quorum quenching mechanism in a novel bacterial strain, Acinetobacter sp. strain XN-10, which degraded the QS molecules of the AHL family that was acting against the QS-mediated pathogenicity. The strain suppressed the pathogenicity of Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum (Pcc), thereby protecting tissue maceration in potatoes, cabbage, and carrots [75][98]. Another study reported a quorum quenching defense mechanism against Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in plants. Upon the interaction of the plant with P. aeruginosa, the plant-secreted QQ molecule (rosmarinic acid) mimicked and competed with the QS pathogenic signal (C4-HSL) and stimulated QS-mediated responses that provide disease protection to the plant, i.e., virulence factors and biofilm formation [65][88].

Figure 2. Schematic representation of quorum sensing (QS) and quorum quenching (QQ) inhibition of signal perception pathways. The binding of QQ agents to the LuxR receptors either inactivates quorum sensing receptors or reduces the quantity of receptors in the QS molecules for targeted gene expression.

Rhizospheric bacteria have been reported to produce antimicrobial signaling compounds. These compounds stimulate systemic resistance in plants against phytopathogens by altering hormonal pathways, e.g., the di-acetyl phloroglucinol (DAPG) that is produced by Pseudomonas sp. [76][99]. It is common that microbially produced VOCs can induce plant growth and resistance to biotic stress [49][77][72,100]. Plants perceive and respond to various VOC signals of PGPR or PGPF origins, such as undecanone and heptanol. For example, 2-heptanol and 2-undecanone, which are produced by B. subtilis and B. amyloliquefaciens, promote the growth of Arabidopsis thaliana when cultivated with these PGPR strains [78][79][101,102].

3.2. Plant–Microbe Signaling

Plants serve as residences for microbial communities, which include mutualists, commensals, and parasitic microorganisms. Plants respond to the microbial signals by secreting chemical compounds, which are known as root exudates. These include low molecular weight compounds (organic acids, sugar, aliphatic acids, fatty acids, amino acids, flavonoids, and secondary metabolites) and high molecular weight compounds (proteins and mucilage) [7][80][81][20,34,103]. The plant–microbe interaction through the secretion of phytochemicals affects the biology of the rhizosphere [82][104]. The secreted chemicals attract rhizospheric microbes toward the plant roots and develop either pathogenic or symbiotic interactions with them. The most studied plant–microbe interaction is the symbiotic relationship of legumes with nitrogen-fixing bacteria. The cascade of signals that is produced upon plant–microbe interaction forms root nodules. Rhizospheric microbes feed on these nodules and in turn provide the plant with an available form of nitrogen. Plant signals for nodule formation have been extensively studied over the last decade [83][84][15,105].

A recent work demonstrated pathogenic plant–microbe interaction through a broccoli plant induced defense system, which released root exudates upon interaction with fungal species. The root exudates (isothiocyanates (ITC) and glucosinolates (GLS)) showed antifungal potential against the rhizospheric microbes Pseudomonas syringae, Sphingomonas suberifaciens, and Fusarium oxysporum [85][106]. The chemical complexity and specificity of the root exudates depend on the genotype of the plant. The chemical signals of root exudates attract specific microorganisms for interaction [7][8][34,35]. For example, cucumber secretes citric acid, which attracts Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, whereas bananas secrete fumaric acid, which attracts B. subtilis N11, but both interactions result in biofilm formation [86][107]. Therefore, specific root exudates recruit specific microbial communities within the rhizosphere. Phytochemicals are also capable of stimulating the QS signaling mechanism in microbes, e.g., the flavonoids that are produced by legumes upregulate the gene expression of AHL genes in rhizobia [87][108].

Plants also release volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from different parts: leaves, flowers, fruits, and roots [88][109]. These include terpenoids, fatty acids, phenylpropanoids, and amino acids that constitute approx. 1% of the total plant secondary metabolites. VOCs can easily cross plant membranes and be released into the atmosphere or soil. In soil, they attract root colonizing pathogens and inhibit their growth [89][110].

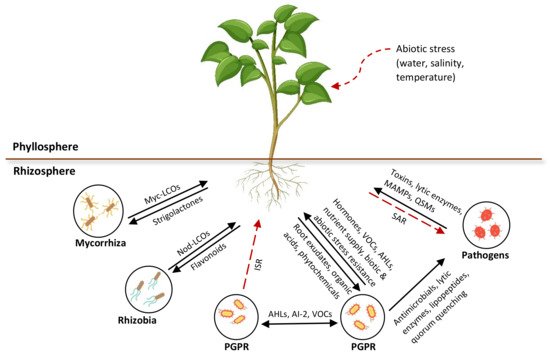

Plant secretions, including root exudates, volatiles, and strigolactones, are widespread signaling compounds that bind with bacterial receptor proteins and elicit a response in microbes that regulates gene expression. The signaling molecules that have been identified so far are known to influence the developmental and defense processes of plants. These phytochemical compounds are responsible for shaping or adapting the rhizomicrobiome due to their specificity and complexity. However, many of these chemical compounds and their target functions are yet to be explored. The rhizosphere signaling mechanisms that are involved in the interactions between microorganisms and between the microorganisms and plants are represented in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Overview of rhizosphere communication in intra- or interspecies signaling among microorganisms and interkingdom signaling between microbes and plants. Myc, mycorrhizal; LCOs, lipo-chitooligosaccharides; Nod, nodulation; VOCs, volatile organic compounds; Ais, autoinducers; AHLs, N-acyl homoserine lactone; QSMs, quorum sensing molecules.