1. Mechanotransduction in MSCs Differentiation

Mechanotransduction is the process by which the natural environment of a cell experiences a physical force that is exerted intracellularly and extracellularly, whereby later, the force is converted into biochemical and electrical signals resulting in cellular responses

[1][25]. The revolutionized multiple molecular pathways from various discoveries and elucidation led to the basic and clinical understanding of the formation and development of tissues and organs. During the growth and emergence of the tissues, there are several involvements of mechanosignaling pathways such as interleukin pathways, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β

[2][26], integrin, MAPK and G protein, β-catenin, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and calcium ion pathways

[3][27]. Extracellular matrix (ECM) and cellular mechanosignaling pathways are actively interconnected in tissue development. These have been demonstrated through MSCs and their response towards intercellular and extracellular signaling, which is transmitted in nuclear to alter protein activity and gene expression while extracellular signaling interrupts cells surrounding the matrix

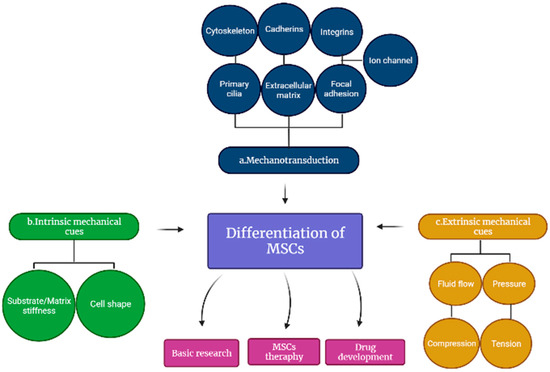

[4][28]; thus, the cell membrane and numerous intracellular components induce both signaling pathways, which have been shown to influence MSC differentiation as indicated in

Figure 1 [5]3 [29]. Meanwhile, the overall understanding of these interactions will be greatly advantageous in tissue engineering and pharmacological interventions that could facilitate the formation and development of tissues and organs.

Figure 13. Differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). The differentiation involves (a) cell membrane and numerous intracellular components, (b) intrinsic and (c) extrinsic mechanical cues that regulate the mechanotransduction of MSCs.

1.1. Cell Membrane and Intracellular Components

1.1.1. Primary Cilia

Most cells in the human body have membrane-encased microtubules that are well known as primary cilia. Primary cilia have been demonstrated as multifunctional antennas, which are considered to detect both chemical and mechanical cues from the internal as well as external environment

[6][30]. The precise functions of primary cilia in mechanotransduction remain unknown because of their dual function as chemosensors and mechanosensors; thus, understanding how MSCs sense and respond to these signals is currently a highly researched area. MSCs could take such ‘outside-in’ and ‘outside-inside-out’ signals; therefore, MSCs differentiation requires more study to dissociate primary cilia’s chemo and mechanical sensing capabilities

[7][31].

1.1.2. Extracellular Matrix

The cell membrane plays a vital role in force transmission to the cell, where direct contact with the ECM occurs. Research on the impact of ECM on cell activities has been extensively studied over the past centuries. Cell adherence, shape, and migration, as well as the activation of signal transduction pathways controlling gene expression and dictating proliferation and stem cell destiny, were established by ECM itself

[7][31]. ECM is composed of a structural macromolecular network which is meant to provide the appropriate structure and environment for delivered cells to take effect

[8][1]. Components of the ECM are made up of solid collagen, laminin, GAGs (hyaluronic acid), chondroitin, and heparin, as well as soluble components such as metalloproteinases that mediate between ECM components

[9]. Basement membranes and connective tissues can be distinguished by their composition and structural organization, which have been attributed primarily to ECM structures. The basement membranes provide two-dimensional support for cells originating from laminin and collagen IV, while connective tissues provide a fibrous three-dimensional scaffold to the cells that are mainly composed of fibrillar collagens, PGs, and GAGs

[10][2].

The dynamic crosstalk between the stem cell and ECM probably seems to alter the shape and ECM composition to secrete ECM structural components and matrix metalloproteinases besides sending mechanical signals via the cytoskeleton fibers. Overall, the idea is to create a favorable niche that induces mechanotransduction signals and guides stem cell fate

[5][29]. Previous studies revealed that the alteration of ECM may lead to several consequences, such as affecting the biochemical and physical properties of ECM and leading to the abnormal organization of the network, which subsequently causes organ failure in humans. Cancer and fibrosis are caused by ECM’s disorganized composition, altering its mechanical properties

[7][31]. In addition, Williams and Marfan syndromes occur due to the mutated gene encoding for elastin

[1][25].

1.1.3. Focal Adhesion

To respond to the external mechanical stimuli, the focal adhesion kinase (FAK) undergoes autophosphorylation, leading to intracellular mechanotransduction, which transduces downstream mechanotransduction

[11][33]. The downstream stimulus involves the contraction of cytoskeletal cells and cell spreading, which develops FAK activation through FAK phosphorylation, which may be boosted by stretching or resistance through a stiff substrate

[12][34]. FAK and the contractile cytoskeletal network develop tension in the cell to induce force into the nucleus

[13][35]. Focal adhesions are mainly derived from the assistance of the integrin and intracellular environment, forming many signaling pathways, which are dependent on the actin cytoskeleton

[12][34]. Many structural proteins, including b-subunits of integrins, vinculin, talin, and the actin cytoskeleton, are involved in their formation

[7][31]. These formations assist integrin binding, other than determining MSCs differentiation and regulating cell shape. In addition, it contributes to signaling cascades to bind and convey signals from the cell to the nucleus.

Furthermore, the assembly of Focal adhesion provides activation of MAPK, GTPases, intracellular calcium concentration, FAK, and paxillin, together with their downstream signals, regulating MSC differentiation

[11][33]. Extrinsic mechanical stimuli are known to induce the activity of Focal adhesions mechanically and their development and have a significant impact on mechanotransduction and MSC differentiation. Focal adhesions have been shown to increase downstream signaling cascades via cell-cell junctions and Focal adhesions interaction, which later generates complex signal production

[14][32], on the other hand, focal adhesion proteins also serve as cytoskeleton anchor sites for actin and integrin filaments

[11][33]. During the directional migration involving cell polarization and nucleus deformation, it has been shown that the migration results in nucleus squeezing and cytoskeleton local reorganization via FAK activation

[3][13][27,35]. According to molecular dynamics studies, the FAK sensor is homeostatic and can auto-adjust to match the stiffness of the substrate

[12][34].

1.1.4. Cytoskeleton

The effects of cytoskeletons on cell functions have been extensively studied. Nowadays, it is well known that cytoskeletons control isometric tension in muscle via the actomyosin filament sliding mechanism

[13][35]. The cytoskeleton is made of filaments that may control shape as well as deliver support to the cell

[15][36]. The tension in cells allows the presence of a cytoskeleton at the binding site of integrin to transfer mechanical signals across cells

[16][37]. The cytoskeletal tension is induced by intracellular signals, substrate stiffness, ligand type, and density, which in turn can impact focal adhesion interaction of the cell-cell junction process and regulate cell shape, which, as previously discussed, is a key regulator of MSCs differentiation

[4][28].

1.1.5. Integrins

Integrins are surrounded by ECM components, which lead to the interconnection of extracellular and cell internal environment to further establish linkage through integrins in the plasma membrane; thus, integrins can determine specific ligand binding due to the α and β subunits present in integrins

[17][39]. It has been found that ECM sends the mechanical signal to integrin to activate signaling cascades involving macro-protein complexes

[18][40], showing that integrin has less control over the cell characteristic compared to ECM

[19][41]. Interestingly, the heterodimeric receptor integrins are shown to be involved in cardiac mechanotransduction through the binding of their extracellular environment to cardiomyocytes

[18][40]. The integrins exhibit 24 types of integrin receptors which are non-covalently bonded to α and β-subunits, which consist of eighteen different α-subunits and eight different β-subunits. The α-subunit integrins induce ECM ligand specificity compared to β-subunits deliver cytoplasmic intracellular signals and later connect the sarcomeres and cytoskeleton; in cardiomyocytes, it is determined to exhibit as α1, α3, α5, α6, α7, α9, α10, β1, β3, and β5 subunits

[20][42].

1.1.6. Cadherins

In contrast to integrins, cadherins are composed of membrane proteins that enable the interaction of cells among themselves. When two cells share the same cadherins, they form a homophilic environment. Configurational changes in cadherins are hypothesized to be caused by calcium, which allows them to bind with other cadherins

[21][43]. Cadherins interact with one other extracellularly and intracellularly in actin cytoskeletons. The intracellular interaction helps cadherin from cadherin-catenin complexes by further binding with the cytoskeleton, which induces MSCs cellular condensation, and eventually generates chondrogenic differentiation to occur

[6][22][30,44]. Additionally, beta-catenin is known to have a role in several signaling pathways

[23][45]. Some researchers believe OFF operates to deconstruct cadherin–catenin complexes, allowing b-catenin to serve as an osteogenic-stimulating molecular signaling molecule in MSCs

[7][22][31,44].

N-cadherins, a cadherin subclass, has also been shown to be essential for MSC myogenesis

[23][45]. A mounting body of work also exists pointing to a key role for the cadherins in the mechanotransduction of MSCs differentiation.

1.1.7. Stretch-Activated Ion Channels (SACs)

Stretch-activated ion channels (SACs) are known to be found in the plasma membrane of various types of cells, which have been shown to influence MSC differentiation with the aid of mechanical signals

[7][31]. It can be explained through the transmission of mechanical tension from induced stress fiber formation and ion channels activation, whereas a subsequent study revealed that inhibiting ROCK resulted in less sensitivity of ion channels. Additionally, the sensitivity of ion channels can be controlled through Rho-dependent actin remodeling

[24][38]. Further inhibition of ion channels is shown to subdue myogenesis, whereas numerous studies suggest ionic concentration greatly impacts myogenic differentiation and induces mechanotransduction

[5][29]. This ionic concentration is influenced by tension caused by stress fiber and ion channel sensitivity. The mechanical signal transmitted upon mechanotransduction encourages SACs activation, subsequently inducing high ion transients in cells that cause cardiac electrical activity, which leads to depolarization in the membrane, and formation of the cytoskeleton as well as provides a long action potential duration

[11][33]. It has been demonstrated that cardiomyocyte contractility occurs through the interchange of intracellular space and the influx of Na

+ and Ca

2+ ions. In addition, streptomycin and gadolinium, known as SAC blockers, can block the intracellular accumulation of Ca

2+ ions, while the increase in intracellular Na

+ levels simultaneously elevates intracellular Ca

2+ via Na

+ and Ca

2+ exchange, which generates rapid contraction in cardiomyocytes

[11][33].

1.2. Intrinsic Substrate Mechanics

The existence of cells in tissues controls the tissue’s stiffness, particularly from soft brain tissue to hard cortical bone. In vitro, it has been shown that substrate stiffness impacts MSCs lineage differentiation

[25][3]. Cellular morphology, transcript indicators, and protein synthesis all showed that MSCs acquired a phenotype that corresponded to tissue stiffness when they were grown on two-dimensional (2D) substrates mimicking neurogenic, myogenic, and osteogenic settings

[8][1]. Current experiments conducted revealed that MSCs are more capable of producing greater adipogenic and chondrogenic effects when grown on soft substrates, whereas those grown on stiffer substrates are more capable of producing a stronger myogenic potential involving muscle

[26][46]. For example, in 2D culture methods, stiffness is often shown to alter cell morphology, but MSCs in three-dimensional (3D) hydrogels have been demonstrated to preserve their spherical shape regardless of the hydrogel’s stiffness

[27][47].

The stiffness of a substrate influences a variety of cell processes, including cell shape, adhesion, migration, differentiation, and proliferation. Cell morphology has recently garnered renewed interest, owing to the possibility that measuring, predicting, and regulating cellular form would be useful in future tissue regeneration. External environmental and biomechanical stimuli alter the morphology of MSCs, which is described by the cell’s ability to balance exterior biomechanical stresses with internal forces in response to those forces. Thus, the stiffness of the biomaterial substrate is directly related to the exerted internal forces.

1.2.1. Substrate Stiffness

While increasing matrix stiffness in both 2D and 3D substrates, the number of integrins attached to the matrix creates an exponential bell curve distribution, with hydrogel stiffness that permits peak bond formation, which allows optimum rigidity for osteogenic differentiation

[22][44]. Myosin contractile machinery inhibition reduced the cell’s dependency on matrix stiffness for connection formation, showing that traction-mediated forces are required for the cell to assess its mechanical cues

[28][51] appropriately. MSC lineage commitment was diminished by inhibiting link formation, demonstrating that matrix stiffness directly impacts MSCs lineage differentiation in cells

[27][47]. MSCs-based myosin contraction is acquired to overcome substrate stiffness in 2D. Substrate stiffness may influence cell shape, especially in 2D cultures, owing to substrate stiffness-mediated changes in integrin binding, adhesion strength, and cell contractility, as illustrated in

Figure 3b. The cytoskeleton’s internal arrangement and interactions with the extracellular matrix (ECM) involving neighboring cells affect the formation of a cell. For these reasons, the observed benefits of MSC differentiation have been demonstrated to be strongly influenced by cell shape

[5][29].

1.2.2. Cell Shape

A study by Steward and Kelly

[6][30] showed that cell shape influences MSC development through seeding cells on micropatterned fibronectin-coated islands of varied sizes and then stimulating the cells with a mixed medium that allows for numerous lineages of differentiation. Small islands had a higher proportion of adipogenic colonies as compared to bigger islands, which had more of an osteogenic colony to determine MSC morphology

[22][44]. This research concluded that cell shape is widely influenced by RhoA GTPase (RhoA) and Rho-associated protein kinase (ROCK) activity. In myosin contraction, ROCK is a Rho effector that regulates contractility. Cells exposed to the adipogenic medium developed an osteogenic phenotype when ROCK was inhibited; it was in contrast when RhoA was activated in osteogenic cells. This suggests that cellular contractility regulates MSC lineage commitment to either an osteogenic or adipogenic pathway

[6][7][22][30,31,44]. TGF-beta 3-stimulated MSCs were either permitted to flatten and disseminate, or to retain their spherical cell shape, as per incomparable research. A myogenic lineage developed in MSCs that were allowed to expand, whereas a chondrogenic lineage developed in those that were maintained rounded

[29][52]. Rac1, known as the Rho GTPase family, was elevated in the spread cells, but it was sufficient to drive myogenesis and inhibit chondrogenesis. However, TGF-b3 and Rac1 were discovered to upregulate a cell-to-cell adhesion molecule, showing that structural alterations to the cytoskeleton play a critical role in defining MSC lineage commitment through numerous routes

[7][31].

1.3. Extrinsic Mechanotransduction Cues

1.3.1. Fluid Flow

Oscillatory fluid flow (OFF) has been shown to control stem cell fate, especially when degraded in the bone, as shown in vivo studies

[5][29]. Actin fibril density, Rho and ROCK signaling, and expression of Runx2, Sox9, and PPARc in murine C3H10T1/2 progenitor cells have been enhanced by OFF according to Woods, Wang, and Beier

[16][37]. When ROCK, NMM II, and actin polymerization inhibitors were added to fluid flow, there was no pro-osteogenic reaction. In the case of adipogenesis and chondrogenesis, it was shown that reducing cytoskeletal tension increased the expression of Sox9 and PPARc while further exacerbated by any fluid flow effects

[7][31]. MSCs lineage pathways are affected by an intact, dynamic actin cytoskeleton, and most importantly, it is necessary for the transmission of OFF. Fluid flow stimulation has also been shown to promote the expression of osteogenic markers in MSCs generated from adipose tissue and bone marrow. MSCs differentiation induces the activation of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases, such as ERK1/2, which have been suggested to increase intracellular calcium ions and additionally activate mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases

[2][26].

Bone marrow-derived MSCs that have undergone cardiomyogenic differentiation could increase direct contributions from increased fluid flow

[24][38]. Several studies revealed that primary cilia play an important role in mechanotransduction, which involves OFF

[6][30]. Another key role of fluid flow is regulating MSCs’ fate in 3D constructions. MSC osteogenesis has been shown repeatedly to be aided by perfusion systems

[30][14]. It has been previously shown that various forms of fluid flow have distinct effects on osteogenesis in a range of scaffolds

[7][31]. Perfusion flow may cause mechanical cues in the cell, such forces could subsequently increase the overall nutrition and gas transport through the gel, making it difficult to interpret the outcome. Additionally, computational models are being extensively used in recent applications to examine the complicated interactions between fluid flow, cells, and the surrounding substrate

[1][25].

1.3.2. Hydrostatic Pressure

MSCs differentiation holds great promise for cell expression and is greatly influenced by hydrostatic pressure (HP). Numerous studies have indicated that cyclic HP promotes Sox9

[24][38], aggrecan, and collagen type II chondrogenic gene expression as well the production of proteoglycans

[22][44] and collagen in MSCs

[31][53]. However, several studies reported the limitation showing that HP has no substantial impact on MSC chondrogenesis due to the encapsulated cells maintaining the response toward HP and relying on the substance within the cells

[6][10][2,30]. Hence, interactions between cell and substrate may influence MSCs response towards HP, which acts as external mechanical stimuli in evaluating MSCs fate. In addition, hydrostatic pressure involves a mechanical stimulus that does not deform, thus, making it difficult to identify possible mechanotransduction pathways. The effect of intracellular calcium concentration induces a possible mechanotransduction signal for chondrocytes involving HP

[7][31]. Na/H exchange in chondrocytes is enhanced by inhibiting the Na/K pump and the Na/K/2Cl pump. Intracellular calcium stores provide an evident increase in chondrocyte intracellular calcium concentration, which has been identified in the 30s of static HP.

1.3.3. Compression

MSCs, together with 3D hydrogels, were directly compressed to provide a significant pro-chondrogenic stimulation

[10][2]. Subsequently, dynamic compression allows chondrogenic gene expression in MSCs and inhibits exogenous growth factor stimulation, resulting in chondrogenesis

[7][31]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that compression and exogenous transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β) stimulus activate identical pathways that lead to increases in (TGF-β1) gene expression via compression

[2][26]. The effects of activating MSCs with soluble (TGF-β1) and Dynamic compression (DC) are still in progress, even though this process induces chondrogenesis. However, it has been revealed that the combined administration of (TGF-β3) and mechanical stimulation may suppress chondrogenesis. Chondrogenesis in MSCs may be enhanced through-loading after extended exposure to (TGF-β1)

[7][31].

1.3.4. Tension

The tensile strain has been implicated as a key regulator in expressing fibrogenic

[32][54], osteogenic

[22][44], and chondrogenic

[6][17][29][30,39,52] in MSCs markers. Cyclic tensile strain exerted in MSCs could increase BMP-2 expression, osteogenic gene expression, and calcium deposition in MSCs. Further, it has been found that MSCs were subjected to cyclic tensile increases in the MAP kinase pathway, which is a key mechanotransduction route in osteogenic differentiation

[7][31].

Overall, an intact and dynamic tension may regulate osteogenic response due to cell-cell interaction. It has been possible to determine the role of cyclic tensile on MSCs directly, studies suggesting MSC were seeded into collagen-GAG scaffolds, subjected to cyclic tensile strain stimulating more proteoglycans than unstrained controls, revealing that this application might cause the release of tensile signal, which eventually may lead to a pro-chondrogenic response

[6][17][30,39]. In addition, the magnitude of cyclic tension has also been found to promote MSC fate; high cyclic tension favors myogenesis, whereas a low strain is more favorable to osteogenesis in the absence of growth stimuli for rabbits seeded with MSCs

[32][33][50,54]. The cyclic tensile strain has consistently been found to influence the expression of proinflammatory cytokines

[34][58]. It has been established that mechanical stimulation not only stimulates osteogenesis but it also helps to sustain bone formation

[5][29].

2. How Mechanotransduction Changes the Clinical Application of MSC

Following mechanotransduction, MSCs have been shown to differentiate into their possible lineages, which can ultimately change the prospect of MSCs in a clinical setting. Mechanical forces can determine the transition of inflammation from systemic autoimmunity to local inflammation. In 2018, Cambré et al. revealed that MSCs in the mechanically sensitive areas of joints sense mechanical stimuli and convert mechanical stimuli into chemical stimuli, causing local inflammation and bone destruction, eventually leading to the development of arthritis

[35][59]. Thus, mechanical forces play an important role in the local inflammatory response in the human body

[10][2]. The acute inflammation process begins with neutrophil activation, which causes inflammatory proteins and chemokines to be secreted to attract monocytes and macrophages

[36][60]. In addition to removing necrotic tissue, macrophages secrete inflammatory cytokines and chemokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and CCL2 to mobilize MSCs to replace hematoma. Shortly thereafter, MSCs are stimulated by various factors in the environment, inducing bone formation and differentiation via either endochondral ossification or intramembranous ossification. Therefore, it is clear that the proper duration of the acute inflammatory phase is important for bone regeneration. However, excessive inflammatory reactions often result in failure of bone repair in bone tissue engineering. Several studies have shown that mechanical stimuli may promote the elimination of inflammation by regulating the interaction between MSCs and macrophages. Therefore, investigations of anti-inflammatory mechanisms and optimal application parameters are of great importance

[37][61].

Overall, the regulation of mechanical stimulation on MSC presented in various studies is of considerable importance for regenerative medicine, as it provides insight for the discovery of mechanosensors, which not only elucidates the processes of mechanotransduction and fate determination but also opens up new avenues for mechanical control in clinical applications. Furthermore, the portrayal of various mechanical stimulation application modalities provides informative assistance in engineering regenerative biomaterials and clinical uses of mechanical stimulation.