Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are important in regulating normal cellular processes whereas deregulated ROS leads to the development of a diseased state in humans including cancers. Several studies have been found to be marked with increased ROS production which activates pro-tumorigenic signaling, enhances cell survival and proliferation and drives DNA damage and genetic instability. However, higher ROS levels have been found to promote anti-tumorigenic signaling by initiating oxidative stress-induced tumor cell death. Tumor cells develop a mechanism where they adjust to the high ROS by expressing elevated levels of antioxidant proteins to detoxify them while maintaining pro-tumorigenic signaling and resistance to apoptosis. Therefore, ROS manipulation can be a potential target for cancer therapies as cancer cells present an altered redox balance in comparison to their normal counterparts.

- mitochondrial ROS

- oxidative stress

- cancer metabolism

- warburg effect

- tumor progression

- apoptosis

- autophagy

- NFκB pathway

- tumor adaptation

- drug resistance

- angiogenesis

- metastasis

- tumor targeting

1. Introduction

2. Source of Reactive Oxygen Species in Cancer Cells

2.1. Mitochondrial ROS

Mitochondria is one of the most prominent sources of reactive oxygen species within a cell which contribute to oxidative stress [4]. The electron transport chain located on the inner mitochondrial membrane generates the majority of mitochondrial ROS during the process of oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). Leakage of electrons at complex I and complex III from ETC leads to a partial reduction of oxygen to form superoxide which undergoes spontaneous dismutation to hydrogen peroxide, both of which are collectively considered as mitochondrial ROS [5]. Endogenous modulators such as NO and Ca2+ have been observed to regulate the production of mtROS by regulating the metabolic states of mitochondria. The mitochondrial Ca2+ levels increase the rate of electron flow in the ETC and thus decrease mtROS generation [6]. However mitochondrial Ca2+ overload increases mtROS production [7]. STAT3, a transcription factor that regulates gene expression in response to cytokines interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-10, also modulates the activity of the ETC [8,9][8][9]. Hence a decrease in expression of STAT3 may be correlated to increasing mtROS at complex I [8]. TNF-α that causes the shedding of TNF-α receptor-1 reducing the severity of microvascular inflammation, has been found to induce a calcium-dependent increase in mt ROS [10]. Studies have shown that many ROS-producing enzymes, like NADPH oxidase, xanthine oxidase, and uncoupled eNOS, can stimulate mtROS production in a process called “ROS-induced ROS” [11,12,13][11][12][13]. Another transcription factor hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) also plays a prominent role in bringing about a reduction in ROS by a number of mechanisms including induction of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 (PKD1), which shunts pyruvate away from the mitochondria; triggering mitochondrial selective autophagy; and induction of microRNA-210 blocking OXPHOS [14]. Low levels of mtROS regulate the stability of HIF-1α leading to hypoxia adaptation while moderate levels of mtROS have been found to regulate the production of proinflammatory cytokines by directly activating the inflammasome and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK). However, high levels of mtROS are capable of inducing apoptosis by oxidation of the mitochondrial pores and autophagy by the oxidation of autophagy-specific gene 4 (ATG4) [5]. Depending on the tumor cell microenvironment, the c-Myc gene controls apoptosis by inducing aerobic glycolysis and/or OXPHOS which is required for the activation of certain tumor suppressor proteins, such as Bax and Bak [15,16,17][15][16][17]. Mitochondria also play an important role in the loss of caveolin 1 (cav-1) in the tumor-associated fibroblast compartment, which is related to the early tumor recurrence, metastasis, tamoxifen-resistance, and aggravated increase in tumor growth [2]. Cav-1 loss induces autophagy and mitophagy, [18] driving the “Reverse Warburg Effect” by a feed-forward mechanism. This onset of inflammation, autophagy, mitophagy, and aerobic glycolysis in the tumor microenvironment is triggered by activation of the transcription factors NFκB and HIF-1α [19,20][19][20]. Mitochondria-generated ROS plays an important role in cell proliferation and quiescence. The pro- or anti-tumorigenic signaling is controlled by a mitochondrial ROS switch of the antioxidant SOD2/MnSOD [21]. Cell proliferation is favored by decreased SOD2/MnSOD activity resulting in increased O2− production whereas proliferating cells transit into quiescence when SOD/MnSOD activity increases resulting in increased H2O2 activity [22]. Inactivation of mitochondrial antioxidant responses like the Thioredoxin reductase (TrxR); which causes reduction of oxidized Trx to produce reduced Trx that reacts with ROS, contributes to increased oxidative stress in cancer cells. Studies have shown that the cellular redox status is impacted by the recruitment of mitochondria by the expression of hTERT. This observation is supported by the presence of hTERT in the mitochondria and since mitochondrial-dependent apoptosis in target cells can be carried about by introducing hTERT inhibitors [23].2.2. Role of Warburg Effect in ROS

The increased metabolic requirements of the cancer cells are met by upregulation of glucose transport and metabolism irrespective of oxygen supply [24]. There is also some evidence that cancer cells decrease mitochondrial respiration in the presence of oxygen, which suppresses apoptosis [25]. Under hypoxic conditions, the accelerated metabolism produces ROS in cancer cells that is countered by the increased NADPH which is met by the upregulated glycolysis [26,27][26][27]. NADPH is an essential cofactor for replenishing reduced glutathione (GSH) which is a critical antioxidant. Therefore, not only are cancer cells’ multiple urgent requirements catered to but cancer cell oxidative stress is also controlled by the Warburg effect [8]. Tumor cells have been reported to switch between the isoforms of pyruvate kinase, used in the last steps of glycolysis [28]. PKM2 the isoform found in high levels in tumor cells is slower and leads to the accumulation of PEP which in turn activates PPP by feedback inhibition of the glycolytic enzyme triosephosphate isomerase (TPI). This produces more NADPH which reduces ROS and further amplifies the inhibitory effect of PKM2 [26[26][27],27], Therefore ROS and PKM2 form a negative feedback loop to maintain ROS in a tolerable and functional range. The ROS-regulated gene, hypoxia-inducible factors (HIF-1α) regulates hypoxia-associated genes, some of which are associated with the Warburg effect and its accompanying pathways and hence, are a target of cancer therapies. PKM2 has been found to be the prolyl hydroxylases (PHDs)-induced coactivator for HIF-1α [8,29][8][29]. HIF-1α also regulates the MYC proto-oncogene which produces MYC protein [30] that regulates genes participating in energy generation and cell growth and proliferation. HIF-1α and MYC activate hexokinase 2 (HK-II) and pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 (PDK1), which inhibits TCA and increases conversion of glucose to lactate [31]. Glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) and lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) are also activated by HIF1 and MYC independently, resulting in increased glucose influx and higher glycolytic rates [13]. Warburg effect increases steady-state ROS condition in cancer cells by producing lactate that is extruded through monocarboxylate transporters to the microenvironment of cancer cells which has no antioxidant properties in contrast to pyruvate, citrate, malate, and oxaloacetate together with the reducing equivalents (NADH.H+) which are antioxidant intermediates. This increased oxidative stress in cancer cells is stopped from reaching cytotoxic levels by some antioxidant effects exerted by hexokinase II (HK II) and NADPH.H+ produced through HMP shunt. Latest studies show tumor cells have the capability to carry about both glycolytic and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) metabolism which makes them resistant to oxidative stress through enhanced antioxidant response and increased detoxification capacity [32]. The changes related to energy metabolism may be correlated to the expression of certain p53 downstream genes regulated by it, including SCO2, TIGAR, and the p53 inducible gene 3 (PIG3) [33,34,35][33][34][35].3. Mechanism of Oxidative Stress-Related Carcinogenesis

3.1. Role of ROS in Tumor Cell Proliferation, Survival and Tumor Progression

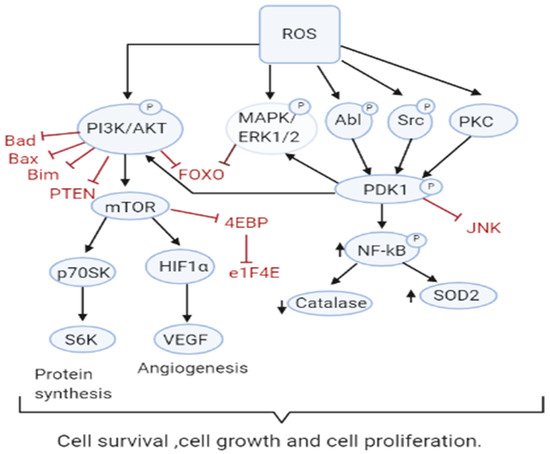

Increased ROS is responsible for the oxidation of negative feedback loop controllers and hence control the actions of other signaling pathways in tumor growth and programmed cell death by the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/PKB) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways [45,46][36][37] (Figure 2Figure 1). Reactive oxygen species generation in cancer cells leads to the inactivation of PTEN that leads to an increase in PI3K/Akt signaling that promotes proliferation. Moreover, the cancer cell cycle progression is promoted when ROS inhibits phosphatase Cdc14B resulting in the activation of cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (Cdk1). As mentioned earlier, the major ROS-regulated gene HIF activates PDK1 that further activates Akt which inhibits the tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC). This downregulates mTOR which is a major regulator of cell growth by controlling mRNA translation, ribosome biogenesis, autophagy, and metabolism [44,47][38][39]. MAPK/ERK1/2 are activated by growth factors and K-Ras stimulated pathways, lead to increased cellular proliferation in cancer cells [48][40]. H2O2 has also been found to be responsible for the activation of ERK1/2 and pro-survival PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, resulting in increased proliferation [49,50][41][42]. Studies on breast, leukemia, melanoma, and ovarian cancer have shown ERK1/2 plays additional roles like cell survival, anchorage-independent growth, and motility [51][43]. The Akt pathway inactivates pro-apoptotic Bad, Bax, Bim, and Foxo transcription factors by phosphorylation thereby promoting cell survival [52,53][44][45]. Akt is activated by the Epithelial growth factor (EGF)-derived H2O2 production, observed in ovarian cancers [54][46]. Cell survival is promoted by the oxidation and inactivation of the negative regulators of PI3K/Akt signaling, i.e., the phosphatases PTEN and PTP1B. The tumor suppressor PTEN has been found to be reversibly inactivated by H2O2 in a variety of cancers [55,56][47][48].

3.2. Role of ROS in Apoptosis-Tumor Suppressive Role

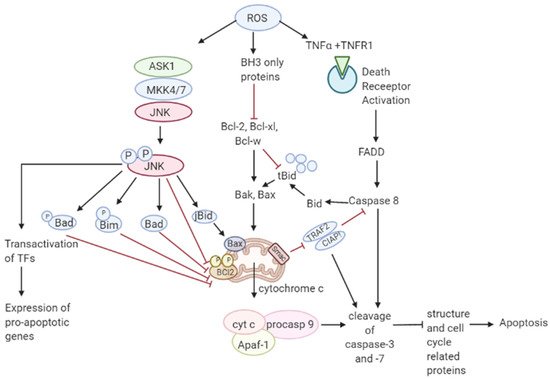

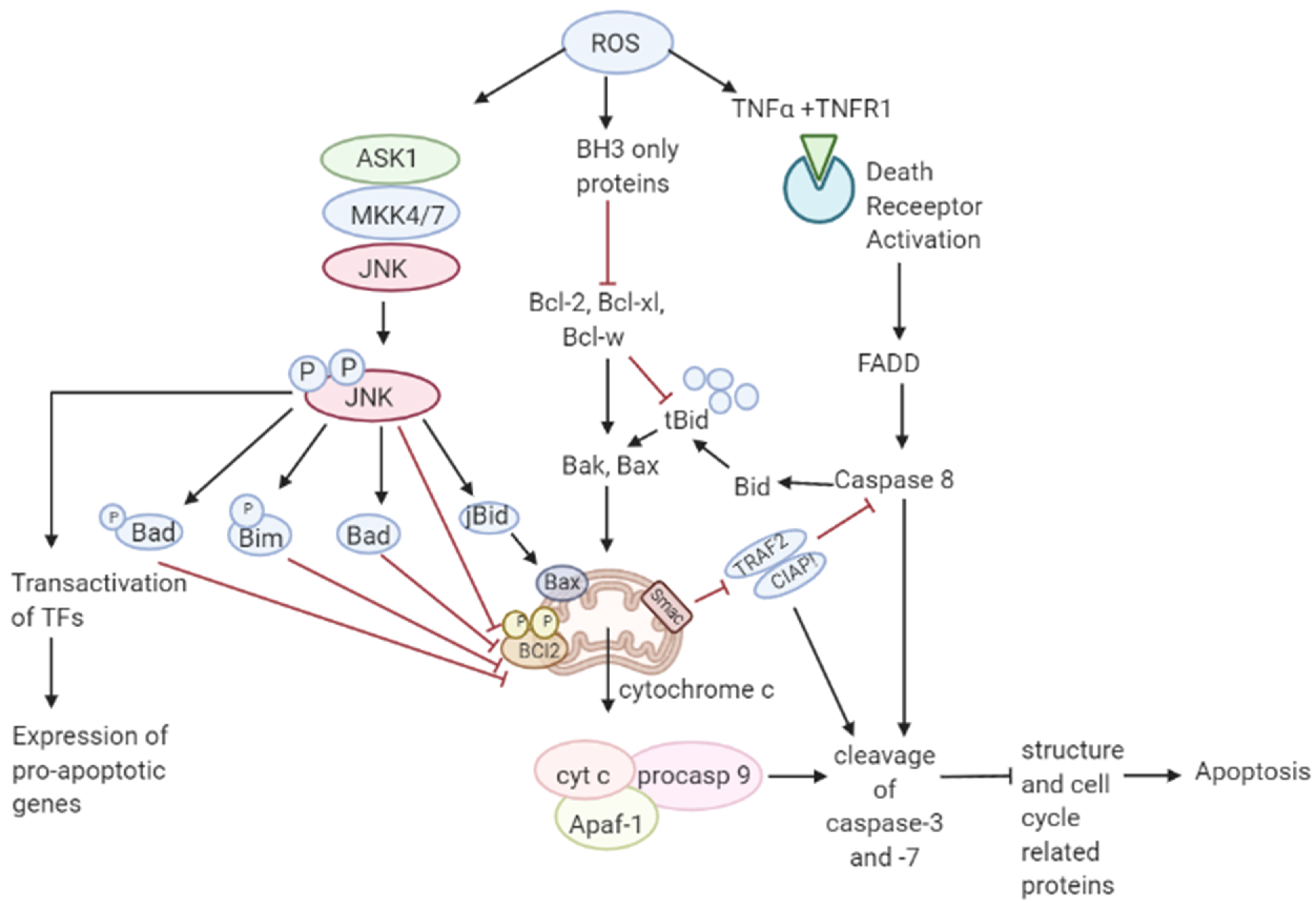

Though ROS activates mitogenic signaling pathways, high levels of ROS have the ability to induce cell cycle arrest, senescence, and cancer cell death either by the initiation of intrinsic apoptotic signaling in the mitochondria or by extrinsic apoptotic signaling by the death receptor pathways [63][55]. ROS induces apoptosis by activating ASK1/JNK and ASK1/p38 signaling pathways in human cancer cells [64,65][56][57]. These pathways are activated when TRX1 is oxidized by H2O2 which subsequently dissociates from ASK1, thereby activating the downstream MAP kinase kinase (MKK)4/MKK7/JNK and MKK3/MKK6/p38 pathways leading to suppression of anti-apoptotic factors [17,66,67,68][17][58][59][60]. It has also been shown that ROS mediate the downregulation of FLICE inhibitory proteins (FLIP proteins) by ubiquitination and subsequent degradation by the proteasome and thereby induce apoptosis by Fas ligand activation [69][61]. Collectively, these observations support a tumor-suppressive role of ROS [70][62]. Recent studies have shown that p53 plays an important role in oxidative stress-related cell death. A regulatory signaling protein of phosphatidyl-3-OH kinase (PI (3) K), p85, participates in the cell death induced by oxidative stress independent of PI (3) K [71][63]. This protein p85 is upregulated by p53. Sir2α has been found to interact with p53 and attenuate p53-mediated functions and hence is a potential cancer therapeutic target [72][64]. JNK pathway activation by elevated ROS production results in apoptosis initiated by intrinsic apoptotic signaling through mitochondria or extrinsic apoptotic signaling mediated by death receptor pathways [73,74,75][65][66][67]. JNK pathway mutations have been found to be inactivated in various cancers suggesting that these pathways may be implicated in apoptotic signaling [76][68]. The activity of apoptotic effectors including the Bcl-2 family of proteins and cytochrome c are affected by the overproduction of ROS leading to the activation of the caspases, a prominent hallmark of apoptosis, resulting in the cleavage of poly ADP ribose polymerase (PARP), DNA fragmentation, and cell death [77][69]. As mentioned in Figure 3 Figure 2, elevated ROS can also result in apoptosis by binding of ligands to death receptors which trigger caspase activation of the initiator caspase 8 leading to cleavage of downstream caspase 3 and Bcl-2 protein Bid to tBid which then translocate into the mitochondria causing the release and translocation of cytochrome c [78,79][70][71]. Cytochrome c forms a complex with apoptotic protein-activating factor 1 (Apaf-1) and pro-caspase 9 inducing the cleavage of downstream caspase-3 and -7. Members of the Bcl-2 family, anti-apoptotic (Bcl-2, Bcl-w, and Bcl-xL) are inhibited, and pro-apoptotic (Bad, Bak, Bax, Bid, and Bim) are activated in apoptotic signaling [80][72]. The loss of cytochrome c from the mitochondria will disrupt and damage the mitochondrial ETC and further cause elevated production of ROS [81][73]. ROS-induced apoptosis can be attributed mainly to decreased GSH levels and the loss of redox homeostasis [82][74].

3.3. Role of ROS in Autophagy-Both Tumor Suppressive and Tumor Promoting Roles

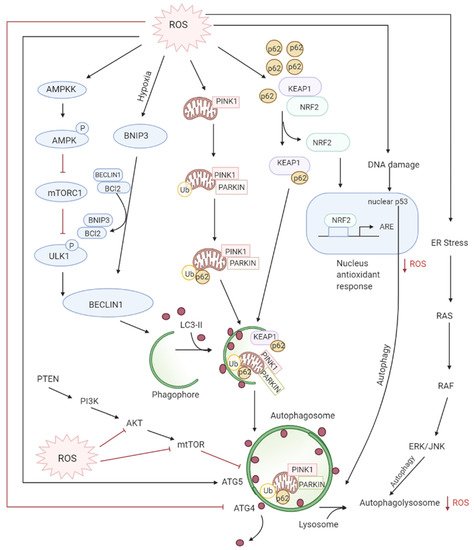

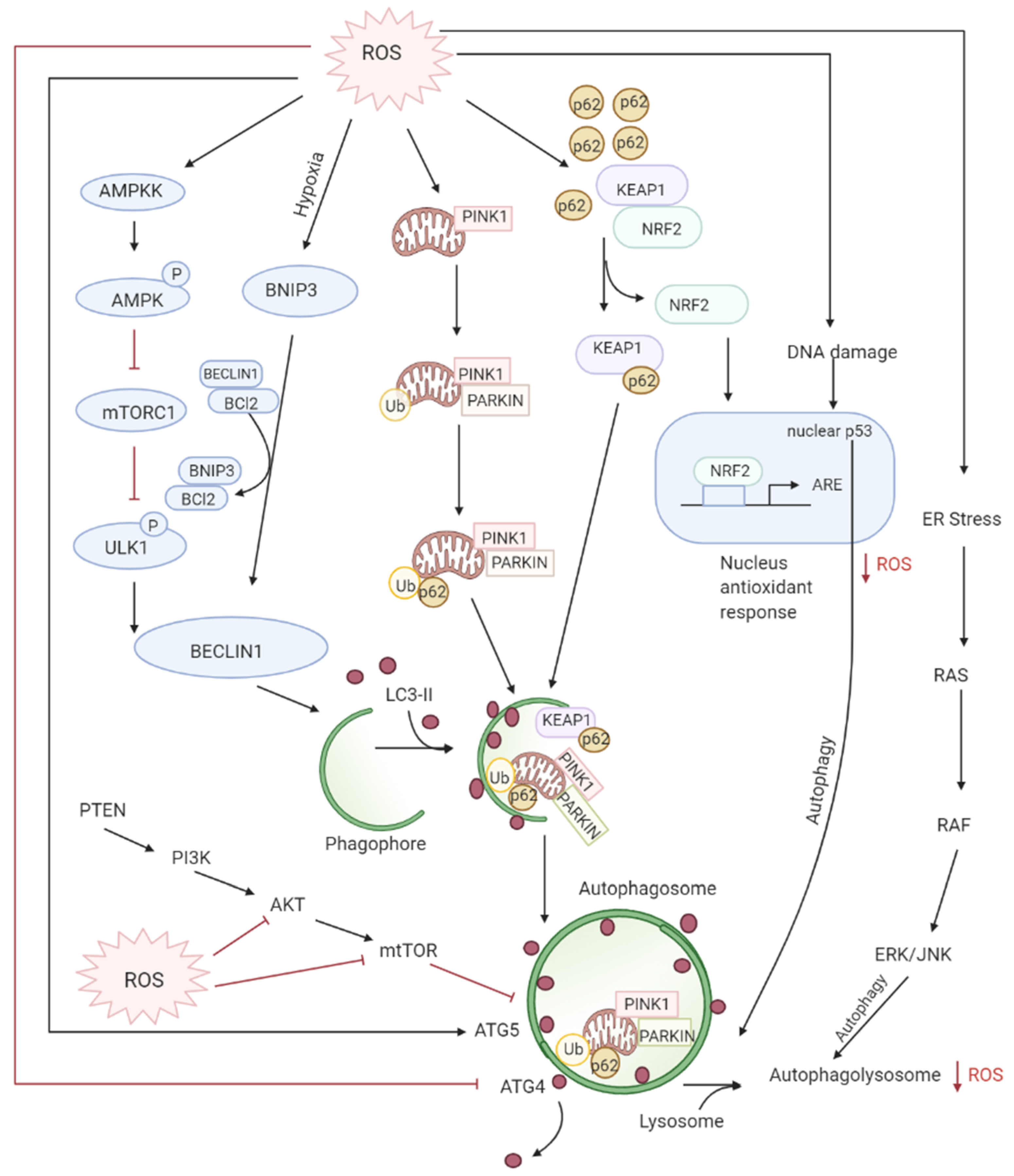

Autophagy is the controlled lysosomal pathway that regulates cellular homeostasis by degradation and recycling of proteins and organelles within a cell [83][75]. ROS regulates autophagy in both direct and indirect ways. Direct regulation involves modification of key proteins like Atg4, Atg5, and Beclin which are involved in the autophagy process. Indirect regulation by ROS involves alteration of signaling pathways that can induce autophagy such as the JNK, p38. ROS have also been found to inhibit Akt signaling and downstream mTOR and thereby induce autophagy [84][76]. Autophagy is one of the first defenses against oxidative stress damage and is upregulated in response to elevated ROS levels [85][77]. Autophagy has been found to be regulated by the mammalian target of rapamycin complex1 (mTORC1) and its upstream activators PI3K and AKT that suppress autophagy whereas negative regulator of PI3K and AKT pathways PTEN has been found to induce autophagy [86][78]. DNA damage caused by the ROS produced by mitochondria leads to activation of p53 that has been documented to regulate autophagy [87][79] (Figure 4Figure 3).

References

- Thannickal, V.J.; Fanburg, B.L. Reactive oxygen species in cell signaling. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2000, 279, L1005–L1028.

- Halliwell, B. Biochemistry of oxidative stress. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2007, 35, 1147–1150.

- Vera-Ramirez, L.; Ramirez-Tortosa, M.; Perez-Lopez, P.; Granados-Principal, S.; Battino, M.; Quiles, J.L. Long-term effects of systemic cancer treatment on DNA oxidative damage: The potential for targeted therapies. Cancer Lett. 2012, 327, 134–141.

- Starkov, A.A. The Role of Mitochondria in Reactive Oxygen Species Metabolism and Signaling. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1147, 37–52.

- Li, X.; Fang, P.; Mai, J.; Choi, E.T.; Wang, H.; Yang, X.-F. Targeting mitochondrial reactive oxygen species as novel therapy for inflammatory diseases and cancers. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2013, 6, 19.

- Robert, F.F. Crosstalk signaling between mitochondrial Ca2+ and ROS. Front. Biosci. 2009, 14, 1197–1218.

- Peng, T.-I.; Jou, M.-J. Oxidative stress caused by mitochondrial calcium overload. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1201, 183–188.

- Handy, D.E.; Loscalzo, J. Redox Regulation of Mitochondrial Function. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2012, 16, 1323–1367.

- Wegrzyn, J.; Potla, R.; Chwae, Y.-J.; Sepuri, N.B.V.; Zhang, Q.; Koeck, T.; Derecka, M.; Szczepanek, K.; Szelag, M.; Gornicka, A.; et al. Function of Mitochondrial Stat3 in Cellular Respiration. Science 2009, 323, 793–797.

- Dada, L.A.; Sznajder, J.I. Mitochondrial Ca2+ and ROS Take Center Stage to Orchestrate TNF-α-Mediated Inflammatory Responses. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 1683–1685.

- Doughan, A.K.; Harrison, D.G.; Dikalov, S.I. Molecular Mechanisms of Angiotensin II–Mediated Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Circ. Res. 2008, 102, 488–496.

- Baudry, N.; Laemmel, E.; Vicaut, E. In vivo reactive oxygen species production induced by ischemia in muscle arterioles of mice: Involvement of xanthine oxidase and mitochondria. Am. J. Physiol. Circ. Physiol. 2008, 294, H821–H828.

- Ceylan-Isik, A.F.; Guo, K.K.; Carlson, E.C.; Privratsky, J.R.; Liao, S.-J.; Cai, L.; Chen, A.F.; Ren, J. Metallothionein Abrogates GTP Cyclohydrolase I Inhibition–Induced Cardiac Contractile and Morphological Defects. Hypertension 2009, 53, 1023–1031.

- Semenza, G.L. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1: Regulator of mitochondrial metabolism and mediator of ischemic preconditioning. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Bioenerg. 2011, 1813, 1263–1268.

- Wise, D.R.; DeBerardinis, R.J.; Mancuso, A.; Sayed, N.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Pfeiffer, H.K.; Nissim, I.; Daikhin, E.; Yudkoff, M.; McMahon, S.B.; et al. Myc regulates a transcriptional program that stimulates mitochondrial glutaminolysis and leads to glutamine addiction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 18782–18787.

- Gao, P.; Tchernyshyov, I.; Chang, T.-C.; Lee, Y.-S.; Kita, K.; Ochi, T.; Zeller, K.I.; De Marzo, A.M.; Van Eyk, J.E.; Mendell, J.T.; et al. c-Myc suppression of miR-23a/b enhances mitochondrial glutaminase expression and glutamine metabolism. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009, 458, 762–765.

- Tomiyama, A.; Serizawa, S.; Tachibana, K.; Sakurada, K.; Samejima, H.; Kuchino, Y.; Kitanaka, C. Critical Role for Mitochondrial Oxidative Phosphorylation in the Activation of Tumor Suppressors Bax and Bak. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2006, 98, 1462–1473.

- Martinez-Outschoorn, U.E.; Pavlides, S.; Whitaker-Menezes, D.; Daumer, K.M.; Milliman, J.N.; Chiavarina, B.; Migneco, G.; Witkiewicz, A.K.; Martinez-Cantarin, M.P.; Flomenberg, N.; et al. Tumor cells induce the cancer associated fibroblast phenotype via caveolin-1 degradation: Implications for breast cancer and DCIS therapy with autophagy inhibitors. Cell Cycle 2010, 9, 2423–2433.

- Outschoorn, U.E.; Lin, Z.; Trimmer, C.; Flomenberg, N.; Wang, C.; Pavlides, S.; Pestell, R.G.; Howell, A.; Sotgia, F.; Lisanti, M.P. Cancer cells metabolically “fertilize” the tumor microenvironment with hydrogen peroxide, driving the Warburg effect. Cell Cycle 2011, 10, 2504–2520.

- Martinez-Outschoorn, U.E.; Balliet, R.M.; Rivadeneira, D.B.; Chiavarina, B.; Pavlides, S.; Wang, C.; Whitaker-Menezes, D.; Daumer, K.M.; Lin, Z.; Witkiewicz, A.K.; et al. Oxidative stress in cancer associated fibroblasts drives tumor-stroma co-evolution. Cell Cycle 2010, 9, 3276–3296.

- Sarsour, E.H.; Venkataraman, S.; Kalen, A.L.; Oberley, L.W.; Goswami, P.C. Manganese superoxide dismutase activity regulates transitions between quiescent and proliferative growth. Aging Cell 2008, 7, 405–417.

- Wang, M.; Kirk, J.S.; Venkataraman, S.; Domann, F.E.; Zhang, H.J.; Schafer, F.Q.; Flanagan, S.W.; Weydert, C.J.; Spitz, D.R.; Buettner, G.R.; et al. Manganese superoxide dismutase suppresses hypoxic induction of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α and vascular endothelial growth factor. Oncogene 2005, 24, 8154–8166.

- Indran, I.R.; Hande, M.P.; Pervaiz, S. Tumor cell redox state and mitochondria at the center of the non-canonical activity of telomerase reverse transcriptase. Mol. Asp. Med. 2010, 31, 21–28.

- Chen, X.; Qian, Y.; Wu, S. The Warburg effect: Evolving interpretations of an established concept. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 79, 253–263.

- Ruckenstuhl, C.; Büttner, S.; Carmona-Gutierrez, D.; Eisenberg, T.; Kroemer, G.; Sigrist, S.J.; Fröhlich, K.-U.; Madeo, F. The Warburg Effect Suppresses Oxidative Stress Induced Apoptosis in a Yeast Model for Cancer. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e4592.

- Anastasiou, D.; Poulogiannis, G.; Asara, J.M.; Boxer, M.B.; Jiang, J.-K.; Shen, M.; Bellinger, G.; Sasaki, A.T.; Locasale, J.W.; Auld, D.S.; et al. Inhibition of Pyruvate Kinase M2 by Reactive Oxygen Species Contributes to Cellular Antioxidant Responses. Science 2011, 334, 1278–1283.

- Hamanaka, R.B.; Chandel, N.S. Warburg Effect and Redox Balance. Science 2011, 334, 1219–1220.

- Sugiyama, T.; Taniguchi, K.; Matsuhashi, N.; Tajirika, T.; Futamura, M.; Takai, T.; Akao, Y.; Yoshida, K. MiR-133b inhibits growth of human gastric cancer cells by silencing pyruvate kinase muscle-splicer polypyrimidine tract-binding protein 1. Cancer Sci. 2016, 107, 1767–1775.

- Luo, W.; Hu, H.; Chang, R.; Zhong, J.; Knabel, M.; O’Meally, R.; Cole, R.N.; Pandey, A.; Semenza, G.L. Pyruvate Kinase M2 Is a PHD3-Stimulated Coactivator for Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1. Cell 2011, 145, 732–744.

- Liu, J.; Levens, D. Making Myc. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2006, 302, 1–32.

- Dang, C.V.; Kim, J.-W.; Gao, P.; Yustein, J. The interplay between MYC and HIF in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2008, 8, 51–56.

- Gentric, G.; Mieulet, V.; Mechta-Grigoriou, F. Heterogeneity in Cancer Metabolism: New Concepts in an Old Field. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2017, 26, 462–485.

- Schmidt, M.W. Element Partitioning: The Role of Melt Structure and Composition. Science 2006, 312, 1646–1650.

- Won, K.Y.; Lim, S.-J.; Kim, G.Y.; Kim, Y.W.; Han, S.-A.; Song, J.Y.; Lee, D.-K. Regulatory role of p53 in cancer metabolism via SCO2 and TIGAR in human breast cancer. Hum. Pathol. 2012, 43, 221–228.

- Kotsinas, A.; Aggarwal, V.; Tan, E.-J.; Levy, B.; Gorgoulis, V.G. PIG3: A novel link between oxidative stress and DNA damage response in cancer. Cancer Lett. 2012, 327, 97–102.

- Salmeen, A.; Andersen, J.N.; Myers, M.P.; Meng, T.-C.; Hinks, J.A.; Tonks, N.K.; Barford, D. Redox regulation of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B involves a sulphenyl-amide intermediate. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003, 423, 769–773.

- Allegra, A.; Pioggia, G.; Tonacci, A.; Casciaro, M.; Musolino, C.; Gangemi, S. Synergic Crosstalk between Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Genomic Alterations in BCR–ABL-Negative Myeloproliferative Neoplasm. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1037.

- Takeuchi, H.; Kondo, Y.; Fujiwara, K.; Kanzawa, T.; Aoki, H.; Mills, G.B.; Kondo, S. Synergistic Augmentation of Rapamycin-Induced Autophagy in Malignant Glioma Cells by Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase/Protein Kinase B Inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 3336–3346.

- Guertin, D.A.; Sabatini, D.M. Defining the Role of mTOR in Cancer. Cancer Cell 2007, 12, 9–22.

- Roberts, P.J.; Der, C.J. Targeting the Raf-MEK-ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade for the treatment of cancer. Oncogene 2007, 26, 3291–3310.

- Irani, K.; Xia, Y.; Zweier, J.L.; Sollott, S.J.; Der, C.J.; Fearon, E.R.; Sundaresan, M.; Finkel, T.; Goldschmidt-Clermont, P.J. Mitogenic Signaling Mediated by Oxidants in Ras-Transformed Fibroblasts. Science 1997, 275, 1649–1652.

- Park, S.-A.; Na, H.-K.; Kim, E.-H.; Cha, Y.-N.; Surh, Y.-J. 4-Hydroxyestradiol Induces Anchorage-Independent Growth of Human Mammary Epithelial Cells via Activation of IκB Kinase: Potential Role of Reactive Oxygen Species. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 2416–2424.

- Steelman, L.S.; Abrams, S.L.; Whelan, J.; Bertrand, F.E.; Ludwig, D.E.; Bäsecke, J.; Libra, M.; Stivala, F.; Milella, M.; Tafuri, A.; et al. Contributions of the Raf/MEK/ERK, PI3K/PTEN/Akt/mTOR and Jak/STAT pathways to leukemia. Leukemia 2008, 22, 686–707.

- Brunet, A.; Bonni, A.; Zigmond, M.J.; Lin, M.Z.; Juo, P.; Hu, L.S.; Anderson, M.J.; Arden, K.C.; Blenis, J.; Greenberg, M.E. Akt Promotes Cell Survival by Phosphorylating and Inhibiting a Forkhead Transcription Factor. Cell 1999, 96, 857–868.

- Limaye, V.; Li, X.; Hahn, C.; Xia, P.; Berndt, M.C.; Vadas, M.A.; Gamble, J.R. Sphingosine kinase-1 enhances endothelial cell survival through a PECAM-1–dependent activation of PI-3K/Akt and regulation of Bcl-2 family members. Blood 2005, 105, 3169–3177.

- Liu, L.-Z.; Hu, X.-W.; Xia, C.; He, J.; Zhou, Q.; Shi, X.; Fang, J.; Jiang, B.-H. Reactive oxygen species regulate epidermal growth factor-induced vascular endothelial growth factor and hypoxia-inducible factor-1α expression through activation of AKT and P70S6K1 in human ovarian cancer cells. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2006, 41, 1521–1533.

- Lee, S.-R.; Yang, K.-S.; Kwon, J.; Lee, C.; Jeong, W.; Rhee, S.G. Reversible Inactivation of the Tumor Suppressor PTEN by H2O2. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 20336–20342.

- Wu, H.; Goel, V.; Haluska, F.G. PTEN signaling pathways in melanoma. Oncogene 2003, 22, 3113–3122.

- Storz, P.; Döppler, H.; Toker, A. Protein Kinase D Mediates Mitochondrion-to-Nucleus Signaling and Detoxification from Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005, 25, 8520–8530.

- Storz, P.; Toker, A. NF-κB Signaling: An ALternate Pathway for Oxidate Stress Responses. Cell Cycle 2003, 2, 9–10.

- Song, J.; Li, J.; Lulla, A.; Evers, B.M.; Chung, D.H. Protein kinase D protects against oxidative stress-induced intestinal epithelial cell injury via Rho/ROK/PKC-delta pathway activation. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2006, 290, C1469–C1476.

- Wang, Y.; Schattenberg, J.M.; Rigoli, R.M.; Storz, P.; Czaja, M.J. Hepatocyte Resistance to Oxidative Stress Is Dependent on Protein Kinase C-mediated Down-regulation of c-Jun/AP-1. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 31089–31097.

- Liou, G.-Y.; Döppler, H.; DelGiorno, K.E.; Zhang, L.; Leitges, M.; Crawford, H.C.; Murphy, M.P.; Storz, P. Mutant KRas-Induced Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress in Acinar Cells Upregulates EGFR Signaling to Drive Formation of Pancreatic Precancerous Lesions. Cell Rep. 2016, 14, 2325–2336.

- Kruiswijk, F.; Labuschagne, C.F.; Vousden, K.H. p53 in survival, death and metabolic health: A lifeguard with a licence to kill. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2015, 16, 393–405.

- Ichijo, H.; Nishida, E.; Irie, K.; ten Dijke, P.; Saitoh, M.; Moriguchi, T.; Takagi, M.; Matsumoto, K.; Miyazono, K.; Gotoh, Y. Induction of apoptosis by ASK1, a mammalian MAPKKK that activates SAPK/JNK and p38 signaling pathways. Science 1997, 275, 90–94.

- Matsuzawa, A.; Nishitoh, H.; Tobiume, K.; Takeda, K.; Ichijo, H. Physiological Roles of ASK1-Mediated Signal Transduction in Oxidative Stress- and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Induced Apoptosis: Advanced Findings from ASK1 Knockout Mice. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2002, 4, 415–425.

- Moon, D.-O.; Kim, M.-O.; Choi, Y.H.; Hyun, J.W.; Chang, W.Y.; Kim, G.-Y. Butein induces G2/M phase arrest and apoptosis in human hepatoma cancer cells through ROS generation. Cancer Lett. 2010, 288, 204–213.

- Saitoh, M.; Nishitoh, H.; Fujii, M.; Takeda, K.; Tobiume, K.; Sawada, Y.; Kawabata, M.; Miyazono, K.; Ichijo, H. Mammalian thioredoxin is a direct inhibitor of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase (ASK) 1. EMBO J. 1998, 17, 2596–2606.

- Tobiume, K.; Matsuzawa, A.; Takahashi, T.; Nishitoh, H.; Morita, K.; Takeda, K.; Minowa, O.; Miyazono, K.; Noda, T.; Ichijo, H. ASK1 is required for sustained activations of JNK/p38 MAP kinases and apoptosis. EMBO Rep. 2001, 2, 222–228.

- Wagner, E.F.; Nebreda, Á.R. Signal integration by JNK and p38 MAPK pathways in cancer development. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2009, 9, 537–549.

- Wang, L.; Azad, N.; Kongkaneramit, L.; Chen, F.; Lu, Y.; Jiang, B.-H.; Rojanasakul, Y. The Fas Death Signaling Pathway Connecting Reactive Oxygen Species Generation and FLICE Inhibitory Protein Down-Regulation1. J. Immunol. 2008, 180, 3072–3080.

- Chio, I.I.C.; Tuveson, D.A. ROS in Cancer: The Burning Question. Trends Mol. Med. 2017, 23, 411–429.

- Yin, Y.; Terauchi, Y.; Solomon, G.G.; Aizawa, S.; Rangarajan, P.N.; Yazaki, Y.; Kadowaki, T.; Barrett, J.C. Involvement of p85 in p53-dependent apoptotic response to oxidative stress. Nat. Cell Biol. 1998, 391, 707–710.

- Luo, J.; Nikolaev, A.Y.; Imai, S.-I.; Chen, D.; Su, F.; Shiloh, A.; Guarente, L.; Gu, W. Negative Control of p53 by Sir2α Promotes Cell Survival under Stress. Cell 2001, 107, 137–148.

- Dhanasekaran, D.N.; Reddy, E.P. JNK signaling in apoptosis. Oncogene 2008, 27, 6245–6251.

- Sastre, J.; Pallardó, F.V.; Viña, J. Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress Plays a Key Role in Aging and Apoptosis. IUBMB Life 2000, 49, 427–435.

- Carmody, R.; Cotter, T. Signalling apoptosis: A radical approach. Redox Rep. 2001, 6, 77–90.

- Role of JNK in Tumor Development—PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12734425/ (accessed on 13 January 2021).

- Groeger, G.; Quiney, C.; Cotter, T.G. Hydrogen Peroxide as a Cell-Survival Signaling Molecule. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009, 11, 2655–2671.

- Fulda, S.; Debatin, K.-M. Extrinsic versus intrinsic apoptosis pathways in anticancer chemotherapy. Oncogene 2006, 25, 4798–4811.

- Yodkeeree, S.; Sung, B.; Limtrakul, P.; Aggarwal, B.B. Zerumbone Enhances TRAIL-Induced Apoptosis through the Induction of Death Receptors in Human Colon Cancer Cells: Evidence for an Essential Role of Reactive Oxygen Species. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 6581–6589.

- Kelekar, A.; Thompson, C.B. Bcl-2-family proteins: The role of the BH3 domain in apoptosis. Trends Cell Biol. 1998, 8, 324–330.

- Chen, Q.; Lesnefsky, E.J. Depletion of cardiolipin and cytochrome c during ischemia increases hydrogen peroxide production from the electron transport chain. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2006, 40, 976–982.

- Lu, C.; Armstrong, J. Role of calcium and cyclophilin D in the regulation of mitochondrial permeabilization induced by glutathione depletion. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007, 363, 572–577.

- Poillet-Perez, L.; Despouy, G.; Delage-Mourroux, R.; Boyer-Guittaut, M. Interplay between ROS and autophagy in cancer cells, from tumor initiation to cancer therapy. Redox Biol. 2015, 4, 184–192.

- Bolisetty, S.; Jaimes, E.A. Mitochondria and Reactive Oxygen Species: Physiology and Pathophysiology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 6306–6344.

- Li, L.; Ishdorj, G.; Gibson, S.B. Reactive oxygen species regulation of autophagy in cancer: Implications for cancer treatment. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2012, 53, 1399–1410.

- Azad, M.B.; Chen, Y.; Gibson, S.B. Regulation of Autophagy by Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS): Implications for Cancer Progression and Treatment. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2009, 11, 777–790.

- Maddocks, O.D.K.; Vousden, K.H. Metabolic regulation by p53. J. Mol. Med. 2011, 89, 237–245.

- Morselli, E.; Galluzzi, L.; Kepp, O.; Vicencio, J.-M.; Criollo, A.; Maiuri, M.C.; Kroemer, G. Anti- and pro-tumor functions of autophagy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Bioenerg. 2009, 1793, 1524–1532.

- Zhang, J.; Ney, P.A. Role of BNIP3 and NIX in cell death, autophagy, and mitophagy. Cell Death Differ. 2009, 16, 939–946.

- Morselli, E.; Galluzzi, L.; Kepp, O.; Mariño, G.; Michaud, M.; Vitale, I.; Maiuri, M.C.; Kroemer, G. Oncosuppressive Functions of Autophagy. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011, 14, 2251–2269.

- Youle, R.J.; Narendra, D.P. Mechanisms of mitophagy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010, 12, 9–14.

- Matsuda, N.; Sato, S.; Shiba, K.; Okatsu, K.; Saisho, K.; Gautier, C.A.; Sou, Y.-S.; Saiki, S.; Kawajiri, S.; Sato, F.; et al. PINK1 stabilized by mitochondrial depolarization recruits Parkin to damaged mitochondria and activates latent Parkin for mitophagy. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 189, 211–221.

- Sandoval, H.; Thiagarajan, P.; Dasgupta, S.K.; Schumacher, A.; Prchal, J.T.; Chen, M.; Wang, J. Essential role for Nix in autophagic maturation of erythroid cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008, 454, 232–235.

- Schweers, R.L.; Zhang, J.; Randall, M.S.; Loyd, M.R.; Li, W.; Dorsey, F.C.; Kundu, M.; Opferman, J.T.; Cleveland, J.L.; Miller, J.L.; et al. NIX is required for programmed mitochondrial clearance during reticulocyte maturation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 19500–19505.

- Komatsu, M.; Kurokawa, H.; Waguri, S.; Taguchi, K.; Kobayashi, A.; Ichimura, Y.; Sou, Y.-S.; Ueno, I.; Sakamoto, A.; Tong, K.I.; et al. The selective autophagy substrate p62 activates the stress responsive transcription factor Nrf2 through inactivation of Keap1. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010, 12, 213–223.

- Taguchi, K.; Fujikawa, N.; Komatsu, M.; Ishii, T.; Unno, M.; Akaike, T.; Motohashi, H.; Yamamoto, M. Keap1 degradation by autophagy for the maintenance of redox homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 13561–13566.

- Takamura, A.; Komatsu, M.; Hara, T.; Sakamoto, A.; Kishi, C.; Waguri, S.; Eishi, Y.; Hino, O.; Tanaka, K.; Mizushima, N. Autophagy-deficient mice develop multiple liver tumors. Genes Dev. 2011, 25, 795–800.

- Mathew, R.; Kongara, S.; Beaudoin, B.; Karp, C.M.; Bray, K.; Degenhardt, K.; Chen, G.; Jin, S.; White, E. Autophagy suppresses tumor progression by limiting chromosomal instability. Genes Dev. 2007, 21, 1367–1381.

- Karantza-Wadsworth, V.; Patel, S.; Kravchuk, O.; Chen, G.; Mathew, R.; Jin, S.; White, E. Autophagy mitigates metabolic stress and genome damage in mammary tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 2007, 21, 1621–1635.

- Choi, A.M.; Ryter, S.W.; Levine, B. Autophagy in Human Health and Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 651–662.

- Liang, X.H.; Jackson, S.; Seaman, M.; Brown, K.; Kempkes, B.; Hibshoosh, H.; Levine, B. Induction of autophagy and inhibition of tumorigenesis by beclin 1. Nat. Cell Biol. 1999, 402, 672–676.

- Laddha, S.V.; Ganesan, S.; Chan, C.S.; White, E. Mutational Landscape of the Essential Autophagy Gene BECN1 in Human Cancers. Mol. Cancer Res. 2014, 12, 485–490.