Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Camila Xu and Version 3 by Camila Xu.

The curaua (or curauá), Ananas comosus var. erectifolius (description given by L.B. Smith), is a type of pineapple plant cultivated for the fiber from its leaves in hot and humid climates, mostly in the Amazon region of Brazil. It can be cultivated on sandy and sandy–clay soils.

- SHCC

- curaua fiber

- PVA

- hybrid composite

- natural fiber

1. Introduction

Strain-hardening cement-based composites (SHCC) are composites reinforced with synthetic fiber, which, after reaching first crack strength, present multiple-cracking-behavior and maintain resistance along with new fine crack formation [1]. The design process of SHCC is based on the micromechanical model [2] where matrix fracture properties (first crack stress), fiber–matrix interaction (bond energy and frictional tension), and the fiber characteristics (length, diameter, and elasticity modulus) are combined to predict the critical fiber volume needed for strain-hardening to occur. Due to its high strain capacity, SHCC has found application in structural elements like bridge decks [3], columns and beams [4], and building dampers [5], which can suffer deformation due to service loads. SHCC is also used in water channels [6] and other hydraulic structures [7][8] because of its capacity to form multiple thin crack patterns that could prevent leakage and present self-healing properties [9].

1.1. Curaua Fiber

The curaua (or curauá), Ananas comosus var. erectifolius (description given by L.B. Smith), is a type of pineapple plant cultivated for the fiber from its leaves in hot and humid climates, mostly in the Amazon region of Brazil. It can be cultivated on sandy and sandy–clay soils. It has been seen that curaua can grow along the paricá tree (Figure 1) and can be used in reforestation.

Figure 1. Curaua plant with paricá tree plantation.

Figure 1. Curaua plant with paricá tree plantation.The fibers are separated from the leaves by a mechanical process [10], then washed and dried for impurities and residue removal [11], as illustrated in Figure 2. The washing process is important for fiber durability because residues can cause fungus growth on the fibers’ surface and reduce their life span. After washing, the fibers are dried for 48 h in natural conditions under direct sunlight at a temperature and humidity specific to the location of the plantation, and then fibers are tied into bundles and are ready for use.

Figure 2. Curaua fiber extraction. (a) Machine used to separate fiber from leaves. (b) Mucilage residue after fiber extraction. (c) Curaua fiber drying in the sun.

Figure 2. Curaua fiber extraction. (a) Machine used to separate fiber from leaves. (b) Mucilage residue after fiber extraction. (c) Curaua fiber drying in the sun.The motivation behind curaua fiber use is in the low initial capital required for start-up production, its simple cultivation methods, and its simple fiber extraction process. All of these aspects create the possibility to improve the economic conditions of the northern Amazonian states of Brazil [12]. The demand for curaua has risen since its application in the automotive industry as an ecological alternative to glass fiber. Because of that movement, new materials are being investigated which could incorporate curaua fiber in their structures as a biocomposite [13] or cement-based composite [14]. Curaua fiber is considered a high-performance fiber due to its high tensile resistance, which is above 600 MPa, and its high Young’s modulus, which is above 38 GPa [15].

1.2. Strain-Hardening Cement-Based Composites (SHCC) CC with Curaua Fiber

After synthetic fibers, such as polyvinyl alcohol fiber (PVA), polyethylene fiber (PE), and polypropylene fiber (PP), natural fibers have found applications in SHCC composites. A comparison of the properties of these fibers and the curaua fiber is shown in Table 1. It can be seen that curaua fiber has a diameter, density, Young’s modulus, and failure strain similar to the synthetic fibers. The design approach presented 10–20 mm curaua fiber, which, after washing cycles and combing, was implemented into a cement matrix with an admixture of coupling agent (vinyltriethoxysilane (VS)) to improve the fiber–matrix bond. The addition of 4.4% per volume fibers with 1% coupling agent presented a multiple-cracking pattern with strain-hardening behavior and a strain capacity of 0.8% [16]. The micromechanical design indicated that the 4% per volume of 20 mm alkali-treated curaua fibers was sufficient for strain-hardening to occur [17]. The strain capacity of the composite increased with fiber length, and for 40 mm, the composites presented a 0.8% strain capacity with a slight tensile strength improvement and new crack formation. The composites exposed to natural weathering did not maintain strain-hardening properties due to fiber–matrix bond deterioration. The lower fiber–matrix bond was not sufficient to transfer the load prior to new crack formation. However, the curaua fiber remained in the composite and did not petrify in the cement matrix. Moreover, the fibers extracted from the composite presented resistance to tensile load, which indicated a favorable durability of the natural fibers in the matrix durability [18].

Table 1. Properties of the synthetic fibers and the natural curaua fiber.

1.3. Hybrid SHCC

Successful trials have been reported for hybrid, strain-hardening composites that incorporate different fibers and that benefit from the combined fiber properties. The combination of steel (0.5%) and PVA (1.5%) fibers in a composite improved fire resistance and reduced explosive spalling when exposed to high temperatures. The admixture of steel fiber prevented the composite from brittle failure after exposure to elevated temperatures above the PVA melting point (225 °C) [21]. The incorporation of PVA and steel fibers into a micromechanical model predicted that 2% of PVA with 0.5% of steel fiber composition would yield an optimal tensile strain capacity [22][23]. Economic and environmental benefits are further reasons for SHCC hybridization. The trial of PVA (1%) with PET (1%) fibers was recommended as a combination for impact resistance composites. The incorporation of 1% of PET fibers provided a similar impact resistance to 2% PVA-SHCC-only composites, but at lower cost [24]. Moreover, the hybrid solution still presents strain-hardening properties and crack control [25]. PVA fibers have also been combined with PE fibers. The hybrid PVA–PE composites presented strain-hardening behavior, and when subjected to 300 cycles of rapid freezing and thawing, they maintained this behavior, but with lower strain capacity [26]. A PE and steel fiber SHCC hybrid has found an application in lap-splicing reinforcing bars, where bond strength and ductility were improved in comparison to a non-hybrid SHCC [27].

2. Compressive Strength

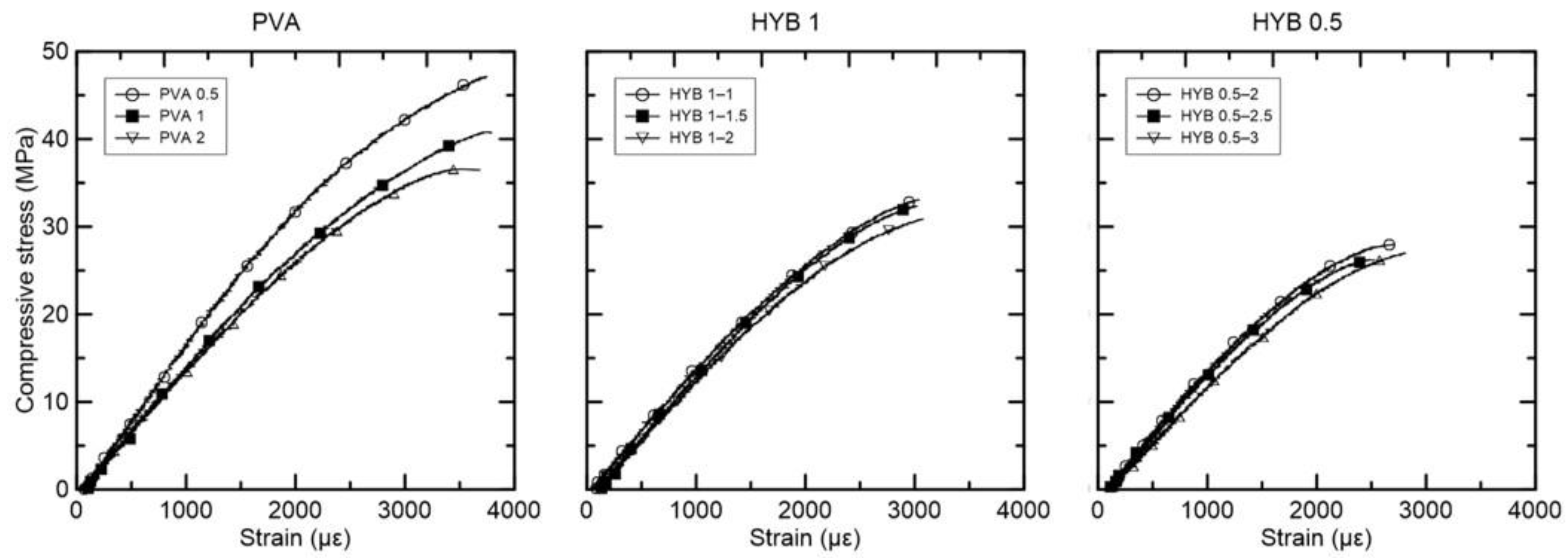

For the composites with only PVA fiber, there is a visible pattern for compressive strength reduction related to increased fiber volume. For the specimens with 0.5% fiber, the highest average compressive strength reported was equal to 45.53 MPa. Doubling the amount of fiber reduced the compressive strength to 41.46 MPa for 1% fiber per volume. This pattern continues for 2% PVA fiber with 35.86 MPa average compressive strength. Figure 3 presents the compressive stress versus strain curves for the composites reinforced with PVA, HYB 1, and HYB 0.5. In the case of hybrid composites, all compositions presented lower compressive strength in comparison to only-PVA fiber composite, which is related to higher fiber volume in total. In the case of hybrid compositions, the total fiber volume was crucial for average compressive strength. Thus, the hybrid compositions with 0.5% PVA fiber presented lower values of 29.59 MPa for 2.5%, 29.74 MPa for 3%, and 26.26 MPa for 3.5% total fiber volume. The hybrid compositions with 1% PVA presented average compressive strength values of 32.24 MPa for 2%, 31.93 MPa for 2.5%, and 29.77 MPa for 3% total fiber volume. In addition, it can be noted that the composite HYB 1–1.5 presented higher compressive strength compared to HYB 0.5–2%. This suggests that the effect of PVA on strength is different for curaua fiber, considering that the composite with 1% curaua presented lower compressive strength than the composite with 0.5% PVA, though both had the same total fiber amount. Figure 3. Compressive stress versus strain curves for the composites reinforced with PVA, HYB 1, and HYB 0.5.

Figure 3. Compressive stress versus strain curves for the composites reinforced with PVA, HYB 1, and HYB 0.5.2.1. Flexural Strength

3. Flexural Strength

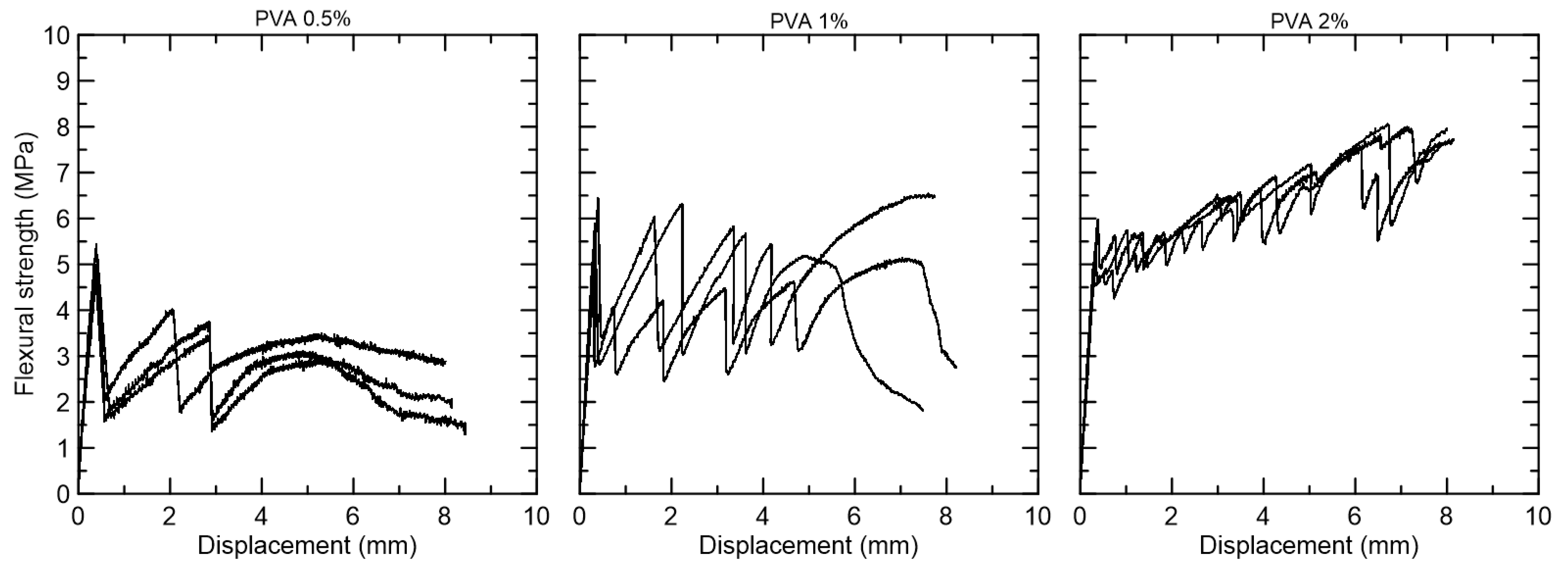

The PVA composites presented an average flexural strength at first crack above 5 MPa. The specimens with 0.5% PVA fiber presented deflection-softening behavior, with only two cracks formed. The specimens with 1% PVA fiber also presented deflection-softening, but with more cracks during the deformation process. The specimens with 2% PVA fiber presented deflection-hardening behavior, with multiple fine cracks formed during the deformation process (Figure 4). Figure 4. Flexural strength versus displacement curves for the composites reinforced with 0.5%, 1%, and 2% PVA fiber.

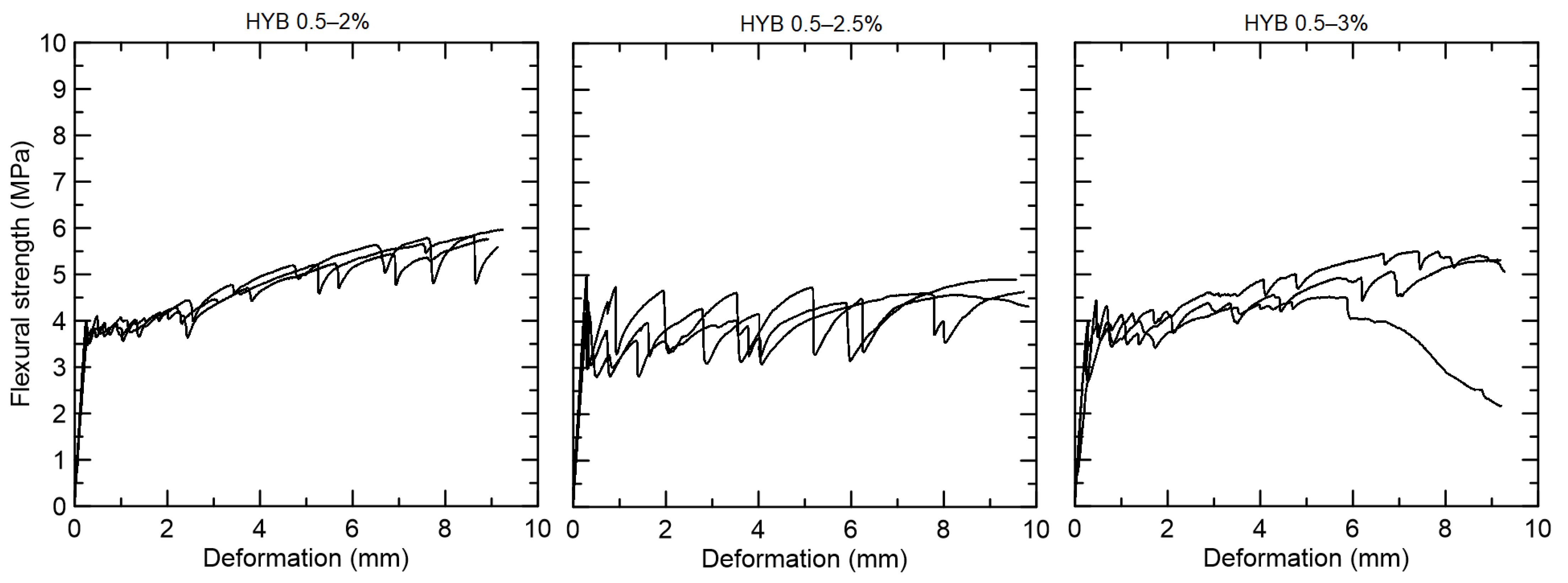

Figure 4. Flexural strength versus displacement curves for the composites reinforced with 0.5%, 1%, and 2% PVA fiber. Figure 5. Flexural strength versus displacement curves for the hybrid composites reinforced with 0.5% PVA and 2%, 2.5%, and 3% curaua fiber.

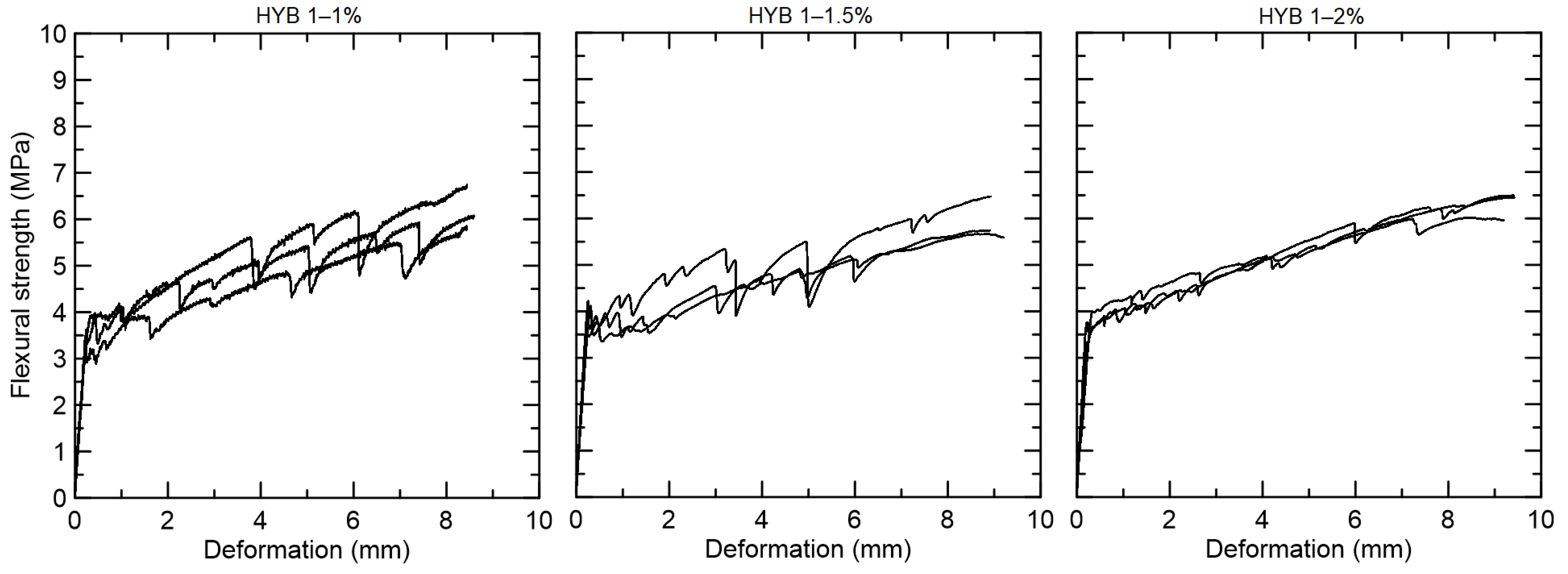

Figure 5. Flexural strength versus displacement curves for the hybrid composites reinforced with 0.5% PVA and 2%, 2.5%, and 3% curaua fiber. Figure 6. Flexural strength versus displacement curves for the hybrid composites reinforced with 1% PVA and 1%, 1.5%, and 2% curaua fiber.

Figure 6. Flexural strength versus displacement curves for the hybrid composites reinforced with 1% PVA and 1%, 1.5%, and 2% curaua fiber.2.2. Tensile Strength

4. Tensile Strength

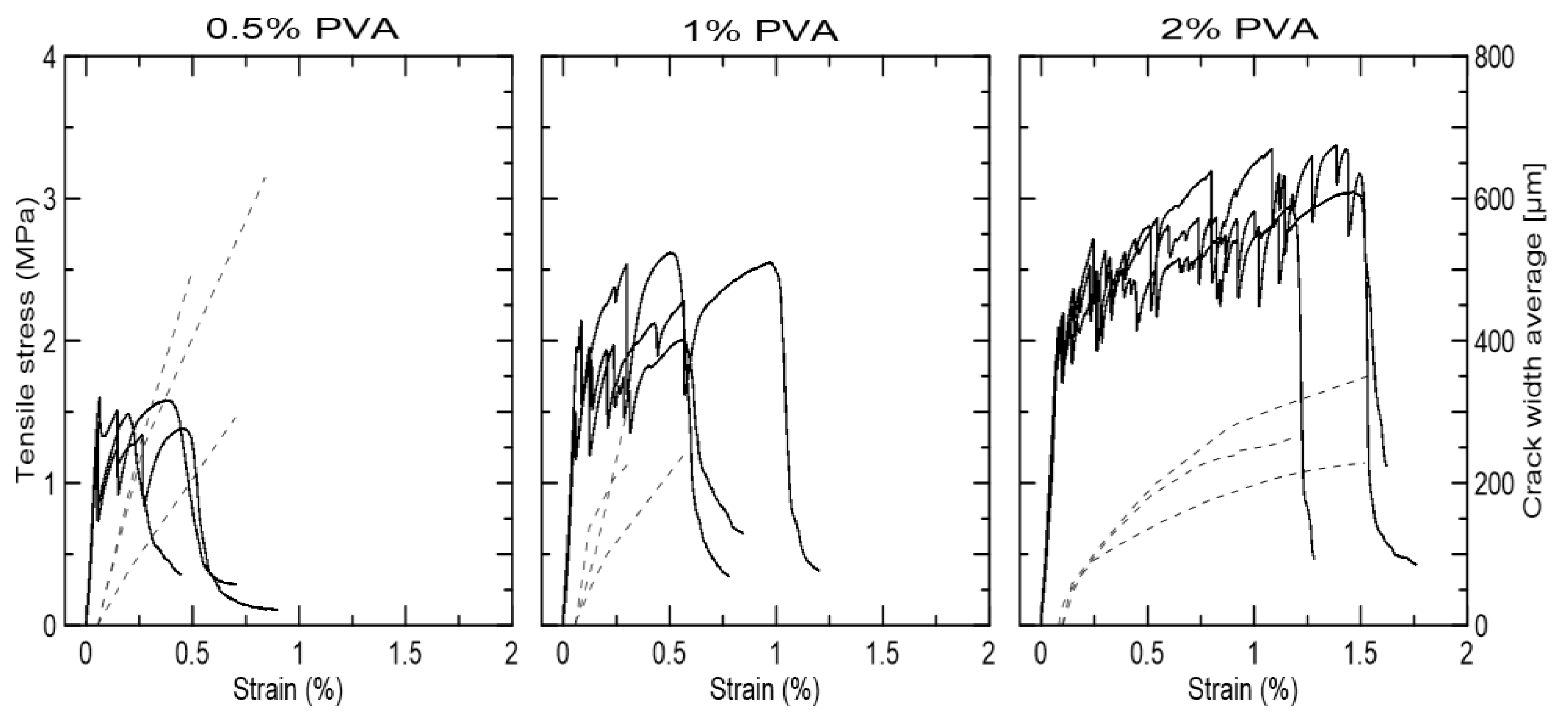

The performance of the composites with only PVA fiber was significantly impacted by the fiber volume. The composites with only 0.5% PVA fiber did not present strain-hardening behavior or crack width control. The first crack occurred at 1.50 MPa and no fine cracks were formed (Figure 7). The specimens with 1% PVA fiber presented the first crack at 1.65 MPa and a maximum tensile strength of 2.39 MPa. The strain-hardening behavior occurred up to strain of 0.5%, but with no crack width control. The specimens with 2% PVA fiber cracked at 1.95 MPa and presented strain-hardening behavior up to 3.12 MPa, and 1.25–1.5% strain with multiple fine cracks of below 350 µm average width. Figure 7. Tensile strength (continues line) versus strain curves and average crack width (dotted line) for the composites reinforced with 0.5%, 1%, and 2% PVA fiber.

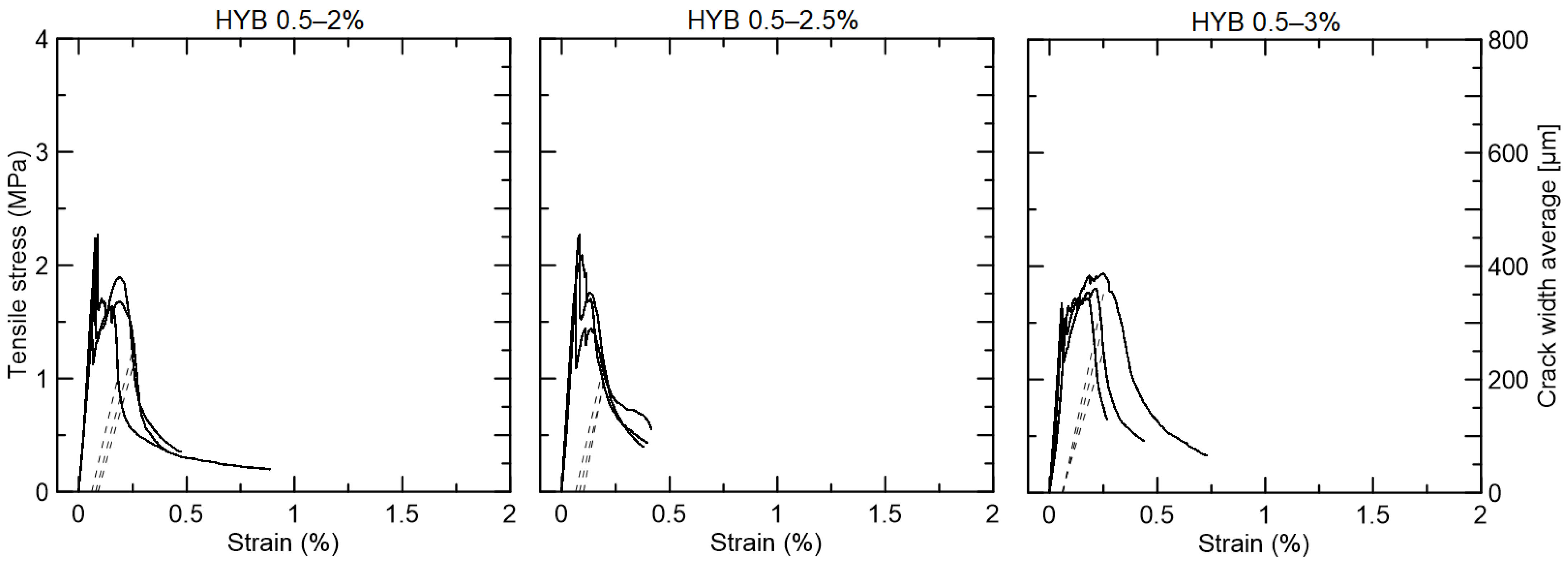

Figure 7. Tensile strength (continues line) versus strain curves and average crack width (dotted line) for the composites reinforced with 0.5%, 1%, and 2% PVA fiber. Figure 8. Tensile strength (continues line) versus strain curves and average crack width (dotted line) for the hybrid composites reinforced with 0.5% PVA and 2%, 2.5%, and 3% curaua fiber.

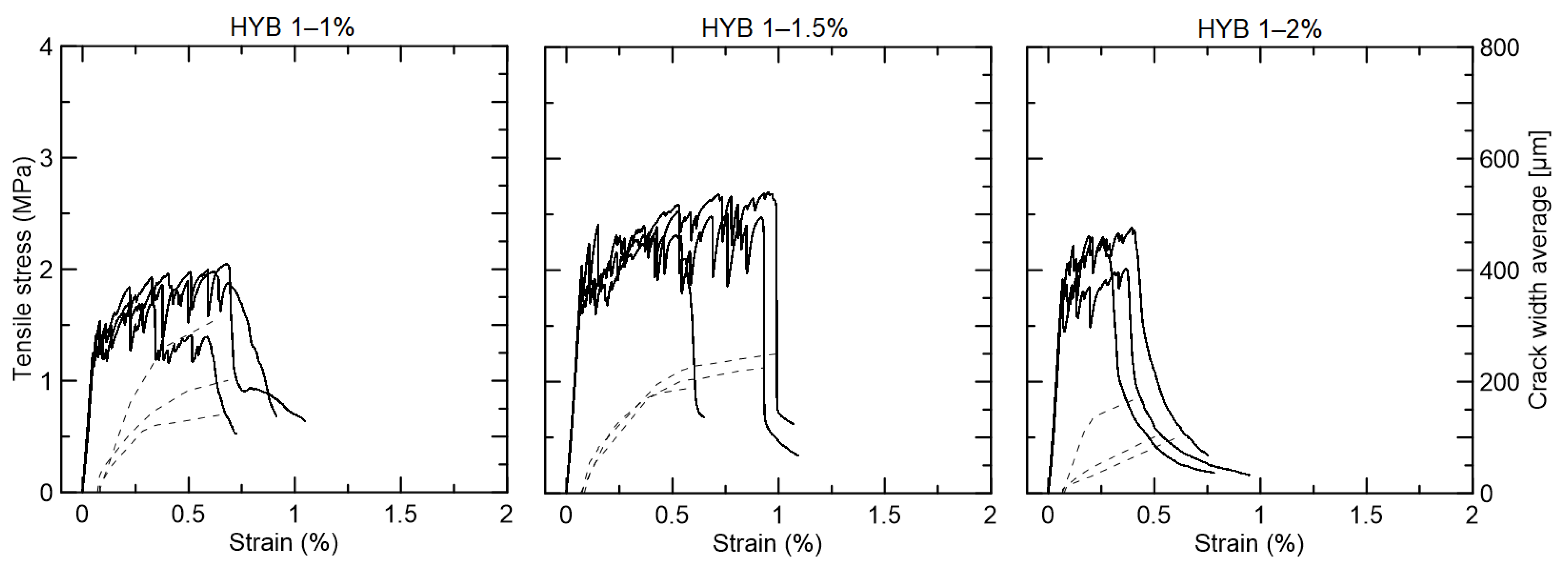

Figure 8. Tensile strength (continues line) versus strain curves and average crack width (dotted line) for the hybrid composites reinforced with 0.5% PVA and 2%, 2.5%, and 3% curaua fiber. Figure 9. Tensile strength (continues line) versus strain curves and average crack width (dotted line) for the hybrid composites reinforced with 1% PVA and 1%, 1.5%, and 2% curaua fiber.

Figure 9. Tensile strength (continues line) versus strain curves and average crack width (dotted line) for the hybrid composites reinforced with 1% PVA and 1%, 1.5%, and 2% curaua fiber.References

- Van Zijl, G.P.A.G.; Wittmann, F.H.; Oh, B.H.; Kabele, P.; Toledo Filho, R.D.; Fairbairn, E.M.R.; Slowik, V.; Ogawa, A.; Hoshiro, H.; Mechtcherine, V.; et al. Durability of strain-hardening cement-based composites (SHCC). Mater. Struct. 2012, 45, 1447–1463.

- Yang, E.H.; Li, V.C. Strain-hardening fiber cement optimization and component tailoring by means of a micromechanical model. Constr. Build. Mater. 2010, 24, 130–139.

- Mitamura, H.; Sakata, N.; Akashiro, K.; Suda, K.; Hiraishi, T. Repair construction of steel deck with highly ductile fiber reinforced cement composites—Construction of Mihara bridge. Bridg. Found. 2005, 39, 88–91.

- Japan Society of Civil Engineers Recommendations for Design and Construction of High Performance Fiber Reinforced Cement Composites with Multiple Fine Cracks (HPFRCC). Concr. Eng. Ser. 2008, 82, 6–10.

- Fukuyama, H. Application of High Performance Fiber Reinforced Cementitious Composites for Damage Mitigation of Building Structures Case study on Damage Mitigation of RC Buildings with Soft First Story. J. Adv. Concr. Technol. 2006, 4, 35–44.

- Li, V.C.; Fischer, G.; Lepech, M. Shotcreting with ECC. Spritzbeton-Tag. 2009, 1–16.

- Liu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Gu, C.; Su, H.; Li, V.C. Influence of micro-cracking on the permeability of engineered cementitious composites. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2016, 72, 104–113.

- Şahmaran, M.; Li, V. Engineered Cementitious Composites. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2010, 2164, 1–8.

- Zhang, P.; Wittmann, F.H.; Zhang, S.; Müller, H.S.; Zhao, T. Self-healing of Cracks in Strain Hardening Cementitious Composites Under Different Environmental Conditions. In Strain-Hardening Cement-Based Composites; Mechtcherine, V., Slowik, V., Kabele, P., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 600–607.

- Onuaguluchi, O.; Banthia, N. Plant-based natural fibre reinforced cement composites: A review. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2016, 68, 96–108.

- Reis, I.N.R.d.S.; Lameira, O.A.; Cordeiro, I.M.C.C. Desenvolvimento do Curauá (Ananas Erectifolius l.b. Smith) a Partir de Adubação Orgânica e de Npk. Semin. Iniciação Científica Embrapa Amaz. Orient.-VIII 2004, 332–334.

- Da Silveira Andrade, A.C.d.S.; Cordeiro, I.M.C.; Ferreira, G.C.; Neves, G.A.M.N. Potencialidades e usos do curauá em plantios florestais, 1st ed.; EDUFRA: Belém, Brazil, 2011; ISBN 978-85-7295-064-0.

- Gutiérrez, M.C.; De Paoli, M.A.; Felisberti, M.I. Cellulose acetate and short curauá fibers biocomposites prepared by large scale processing: Reinforcing and thermal insulating properties. Ind. Crops Prod. 2014, 52, 363–372.

- D’Almeida, A.L.F.S.; Melo Filho, J.A.; Toledo Filho, R.D. Use of curaua fibers as reinforcement in cement composites. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2009, 17, 1717–1722.

- Ferreira, S.R.; de Andrade Silva, F.; Lima, P.R.L.; Toledo Filho, R.D. Effect of hornification on the structure, tensile behavior and fiber matrix bond of sisal, jute and curaua fiber cement based composite systems. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 139, 551–561.

- Soltan, D.G.; das Neves, P.; Olvera, A.; Savastano Junior, H.; Li, V.C. Introducing a curauá fiber reinforced cement-based composite with strain-hardening behavior. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 103, 1–12.

- Zukowski, B.; de Andrade Silva, F.; Toledo Filho, R.D. Design of strain hardening cement-based composites with alkali treated natural curauá fiber. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2018, 89, 150–159.

- Zukowski, B.; dos Santos, E.R.F.; dos Santos Mendonça, Y.G.; de Andrade Silva, F.; Toledo Filho, R.D. The durability of SHCC with alkali treated curaua fiber exposed to natural weathering. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2018, 94, 116–125.

- Liu, J.; Lv, C. Properties of 3D-Printed Polymer Fiber-Reinforced Mortars: A Review. Polymers 2022, 14, 1315.

- Coelho de Carvalho, L.M.; Dal Toé Casagrande, M. Mechanical behaviour of reinforced sand with natural curauá fibers through full scale direct shear tests. E3S Web Conf. 2019, 92, 1–5.

- Liu, J.C.; Tan, K.H. Fire resistance of strain hardening cementitious composite with hybrid PVA and steel fibers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 135, 600–611.

- Yu, J.; Lu, C.; Chen, Y.; Leung, C.K.Y. Experimental determination of crack-bridging constitutive relations of hybrid-fiber Strain-Hardening Cementitious Composites using digital image processing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 173, 359–367.

- Yu, J.; Chen, Y.; Leung, C.K.Y. Micromechanical modeling of crack-bridging relations of hybrid-fiber Strain-Hardening Cementitious Composites considering interaction between different fibers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 182, 629–636.

- Lu, C.; Yu, J.; Leung, C.K.Y. Tensile performance and impact resistance of Strain Hardening Cementitious Composites (SHCC) with recycled fibers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 171, 566–576.

- Yu, J.; Yao, J.; Lin, X.; Li, H.; Lam, J.Y.K.; Leung, C.K.Y.; Sham, I.M.L.; Shih, K. Tensile performance of sustainable Strain-Hardening Cementitious Composites with hybrid PVA and recycled PET fibers. Cem. Concr. Res. 2018, 107, 110–123.

- Yun, H. Do Effect of accelerated freeze-thaw cycling on mechanical properties of hybrid PVA and PE fiber-reinforced strain-hardening cement-based composites (SHCCs). Compos. Part B Eng. 2013, 52, 11–20.

- Choi, W.C.; Jang, S.J.; Yun, H. Do Bond and cracking behavior of lap-spliced reinforcing bars embedded in hybrid fiber reinforced strain-hardening cementitious composite (SHCC). Compos. Part B Eng. 2017, 108, 35–44.

More