Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Dean Liu and Version 4 by Dean Liu.

Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) is a component of cell-free DNA (cfDNA) that is shed by malignant tumors into the bloodstream and other bodily fluids. ctDNA can comprise up to 10% of a patient’s cfDNA depending on their tumor type and burden.

- circulating tumor DNA

- cell-free DNA

- biomarkers

1. Cell-Free DNA and Circulating Tumor DNA

Cell-free DNA (cfDNA) is comprised of double-stranded DNA ranging between 150 and 200 base pairs in length and circulates mostly in blood [1]. Passive release via apoptosis, necrosis, and phagocytosis account for the primary mechanisms of cfDNA release. In healthy individuals, most of the cfDNA originates from hemopoietic cells such as erythrocytes, leukocytes, and endothelial cells [2]. Normal tissue that undergoes damage by ischemia, trauma, infection, or inflammation can also release cfDNA [3]. Active secretion via exosomes or protein complexes also contributes to cfDNA [4]. cfDNA has a short half-life ranging between 16 min and 2.5 h, although it may be longer when it is bound to protein complexes or inside membrane vesicles [5][6], and it is cleared from circulation via nuclease action [7] and renal excretion into the urine [8].

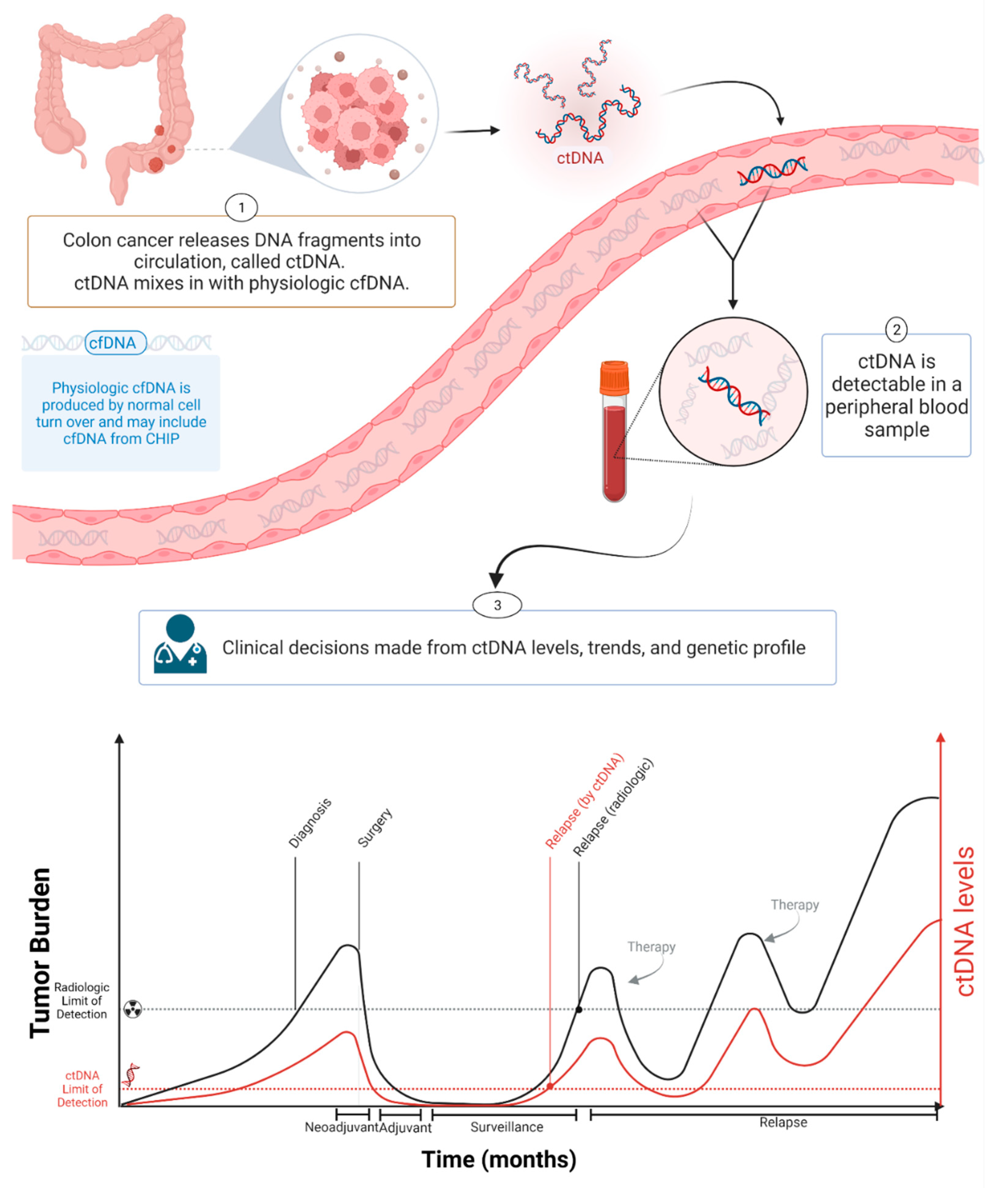

Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) is a component of cfDNA that is shed by malignant tumors into the bloodstream and other bodily fluids, including blood, urine, pleural fluid, ascites, and saliva (Figure 1). In the case of brain tumors, including brain metastatic lesions, ctDNA can also be found in the cerebrospinal fluid [9][10]. ctDNA typically constitutes a small proportion of an individual’s total cfDNA [11]. Plasma samples are preferable to serum for ctDNA analysis as the latter contain larger quantities of DNA from leukocytes lysed during the clotting process, thereby increasing the background to signal ratio and interfering with ctDNA detection [12]. Compared to cfDNA derived from non-cancer cells, ctDNA is shorter [13][14][15]. cfDNA from normal cells has a fragment size of ~166 bp, and ctDNA has a fragment size of ~146 bp because of the loss of the H1 linker [16]. Plasma ctDNA is also generally more fragmented than non-mutant cfDNA, with a maximum enrichment between 90 and 150 bp, as well as enrichment in the size range 250–320 bp [16].

Figure 1. ctDNA during cancer progression. Created with BioRender.com.

The amount of cfDNA in cancer patients varies widely, and is usually higher than in the blood of healthy controls [17]. In healthy donors, the mean value of plasma cfDNA is ~10.3 ng/mL plasma (range: 5–50 ng/mL plasma), with a median value of 5 ng/mL plasma [18][19]. cfDNA in cancer patients is usually below 100 ng/mL plasma and approximately below 17,000 genome equivalent (GE) per ml of plasma (assuming 6 pg of DNA per diploid human genome) [17]. The concentration of ctDNA can exceed 10% of the total cfDNA in patients with advanced-stage cancers [20] but is much lower in patients with low tumor burden, such as patients with localized disease [20][21][22]. In colon cancer, the concentration of ctDNA in pretreatment plasma is significantly lower in stage I patients compared with stage II–III patients [23] and the ctDNA fraction of the total cfDNA is often less than 0.1% in patients with early stage colon cancer following curative surgery [21]. Varying ctDNA levels are associated with clinical and pathological features of cancer, including stage, tumor burden, localization, vascularization, and response to therapy [11][20][24][25][26]. Furthermore, ctDNA levels vary due to differences in tumor grade (e.g., indolent vs. fast progressing), shedding rates, and other biological factors [27]. Bettegowda et al. reported how ctDNA detectability varies among different tumor types [20]. Most patients with stage III ovarian and liver cancers and metastatic cancers of the pancreas, bladder, colon, stomach, breast, esophagus, and head and neck, as well as patients with neuroblastoma and melanoma, harbored detectable levels of ctDNA [20]. In contrast, less than 50% of patients with medulloblastomas or metastatic cancers of the kidney, prostate, or thyroid, and less than 10% of patients with gliomas, harbored detectable ctDNA [20].

2. Role of ctDNA in Management of Colorectal Cancer

CRC is the third most common cancer worldwide and the second leading cause of cancer-related death, with 1.9 million newly diagnosed cases each year [28]. In the US, the 5-year survival rate for people with localized stage CRC is 90%; if the cancer has spread to the surrounding organs and/or the regional lymph nodes, the 5-year survival rate is 72%; and for stage IV CRC, the 5-year survival rate is 14% [29]. The current standard of care for patients with early stage CRC includes the surgical resection of the tumor followed by adjuvant chemotherapy in selected patients [30][31]. Most patients with stage II CRC are not treated with chemotherapy; however, approximately 10–15% have residual disease after surgery [32]. The identification of this patient population and treatment with chemotherapy could potentially reduce their risk of recurrence. Conversely, most patients with stage III CRC receive chemotherapy despite more than 50% being cured by surgery [33][34][35]. Furthermore, approximately 30% of the chemotherapy-treated patients with stage III CRC experience recurrence, making them candidates for additional therapy [32]. Thus, improved tools to identify the patient population who would benefit from chemotherapy are greatly needed. Early diagnosis of recurrent disease is another significant unmet clinical need in CRC. After the completion of definitive treatment, surveillance is recommended to detect recurrence sufficiently early for potentially curative surgery [30][31]. Despite surveillance, many recurrence events are detected late, and only 10–20% of metachronous metastases are treated with curative intent [36]. Nevertheless, currently recommended follow-up programs, consisting of the use of imaging techniques plus plasma carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) monitoring, are suboptimal, failing to detect MRD and mostly diagnosing only far advanced relapses [37]. The current goal standard for assessing initial disease bulk and for defining treatment response is the image-based Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST). RECIST limitations include low inter- and intra-observer reproducibility and limited categorization [38] and CEA’s lack of sensitivity and specificity [39][40][41]. Therefore, there is a need for better biomarkers that can detect patients at high risk of recurrence to enable appropriate follow-up and therapeutic strategies for early recurrence detection and curative treatment [42]. Plasma ctDNA has emerged as a promising biomarker for the longitudinal assessment of tumors throughout disease management. In CRC, there are multiple indications for which ctDNA can assist with clinical decision making. Recently, the Colon and Rectal-Anal Task Forces of the United States National Cancer Institute provided detailed guidance in the standardization and efficient development of ctDNA technology [43]. In the setting of metastatic CRC, they recommended that the ideal ctDNA assay should involve a multigene panel that enables high-depth sequencing of the most commonly altered genes in order to capture the changes associated with non-targeted as well as targeted therapies. With such an assay, the presence of any CRC-related somatic alteration could be used to indicate a positive test, and the highest VAF of the alteration could be used to define ctDNA concentration [43]. The assay would need to be performed prior to the start of the treatment and then again soon after starting treatment to guide the determination of an early clinical response [43]. The sequencing of the DNA from CRC identified several genes that are recurrently mutated [44], and these tumor-specific mutations can be detected in the cfDNA of peripheral blood in most patients with metastatic disease. Genetic variants from 1397 patients with advanced CRC were studied using ctDNA and compared with data from three independent tissue-based CRC sequencing databases [45]. The spectrum and frequency of genomic alterations identified in ctDNA demonstrate a striking similarity to results from these three large CRC tumor tissue sequencing databases [45]. The genes most mutated in colon cancer patients are KRAS, BRAF, PIK3CA, TP53, APC, FBXW7, NRAS, CTNNB1, SMAD4, PTEN, ERBB3, and EGFR [23][46]. Epigenetic analysis of cfDNA/ctDNA might contribute to the identification of gene hypermethylation [47][48]. The methylation of HLTF and HPP1 genes was associated with worse survival in CRC [49][50]. Lee et al. [51] analyzed the promoter methylation of the Septin 9 gene among patients with stage I–II CRC and suggested that its methylation might be associated with lower disease-free survival. Herbst et al. [52] suggested that the detection of HPP1 methylation in cfDNA might be used as a prognostic marker and an early marker to identify patients who will likely benefit from a combination of chemotherapy and bevacizumab. However, the methylation status of cfDNA and its application to detect MRD and response to treatment are studied less intensively [53][54].3. Role of ctDNA in the Detection of Minimal Residual Disease in Colorectal Cancer

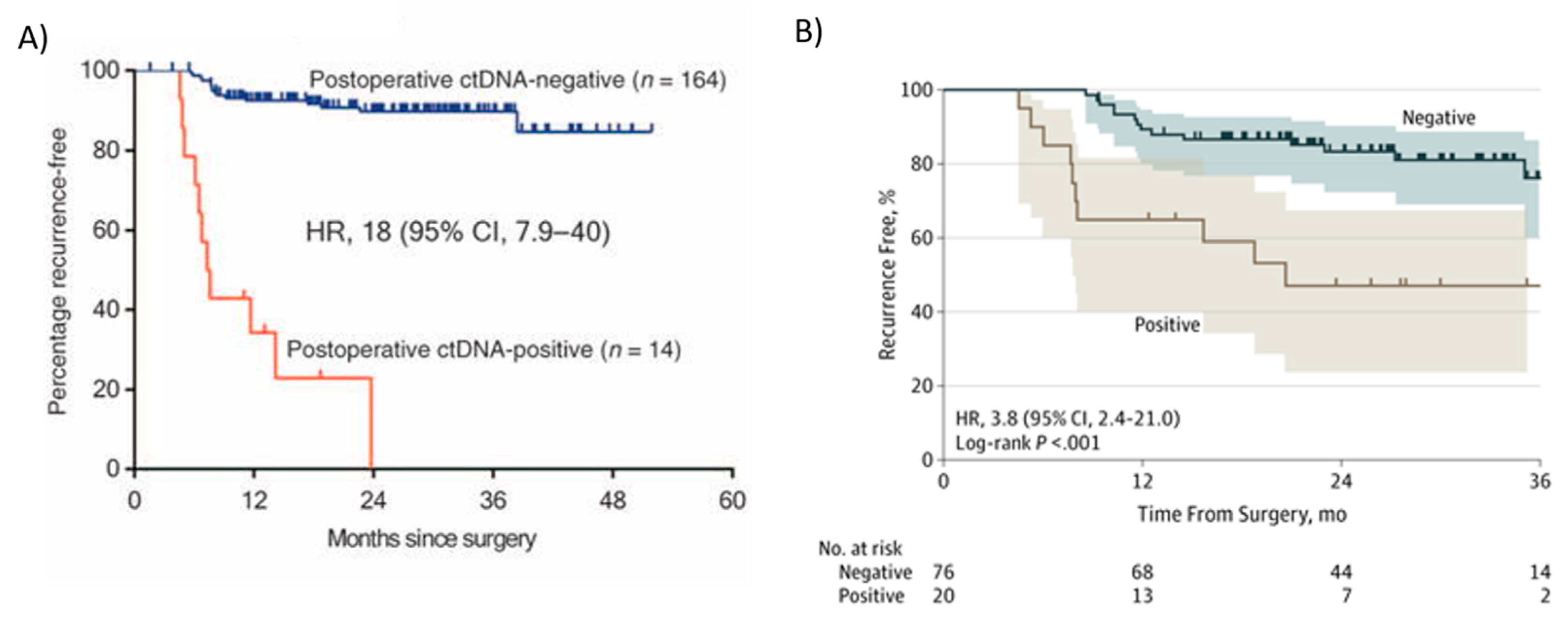

In patients with stage II colon cancer (~25% of all colorectal cancer), management after surgical resection remains a clinical dilemma, with about 80% cured by surgery alone. Adjuvant chemotherapy is more frequently offered to high-risk stage II patients. However, an overall survival benefit from adjuvant therapy in patients with stage II colon cancer, including those with the high-risk disease based on standard clinicopathologic criteria or gene signatures, remains to be conclusively demonstrated [55]. The challenge in demonstrating a benefit is in part due to the overall low risk of recurrence in patients with stage II colon cancer. The decision to treat or not to treat stage II colon cancer patients with adjuvant chemotherapy remains one of the most challenging areas in colorectal oncology. Currently, up to 40% of stage II patients undergo adjuvant therapy in routine clinical care [56], committing to 6 months of chemotherapy, with the associated risk of potentially serious adverse events and without a method to monitor the impact of adjuvant therapy, for an absolute risk reduction of 3–5%. Although multiple clinicopathological markers are now validated and can be combined to define low- and high-risk groups, only a minority of defined high-risk patients will develop recurrence. Diagnostic approaches that better predict the disease course in this patient population are therefore urgently required. Tie et al., using a tumor-informed Safe-SeqS platform-based ctDNA assay, reported two prospective, multicenter cohort studies, one in stage II (n = 230) [21] and the other in stage III (n = 96) patients [57], showing that ctDNA significantly outperformed standard clinicopathologic characteristics as a prognostic marker. In these studies, tumor tissue was analyzed for somatic mutations in 15 genes commonly known to be mutated in CRC, and one mutation identified in the tumor tissue (the mutation with the highest mutant allele fraction, MAF) was selected for ctDNA testing in each patient. Among 230 patients with resected stage II colon cancer, the presence of ctDNA in postoperative plasma samples was strongly associated with recurrence in those who did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy (Figure 2A) [21]. Among the patients in the stage II cohort [21] who did not receive adjuvant chemotherapy (n = 178), 79% of the patients (11 out of 14) with detectable ctDNA postoperatively (4 to 10 weeks after surgery) had cancer recurrence at a median follow up duration of 27 months (HR 18, 95% CI 7.9–40; p < 0.001) (Figure 2A). Conversely, only 9.8% (16 out of 164) of the patients with undetectable postoperative ctDNA had a cancer recurrence (Figure 2A) [21]. In conclusion, Tie et al. [21] demonstrated that stage II colon cancer patients who were ctDNA positive postoperatively were at extremely high risk of radiologic recurrence when not treated with chemotherapy. This risk is greater than in patients with stage III colorectal cancer, who are routinely treated with adjuvant therapy. Conversely, patients with negative ctDNA postoperatively were at low risk of radiologic recurrence (3-year RFS of 90%), not dissimilar to patients with stage I colorectal cancer [58], defining a group where adjuvant chemotherapy is less likely to be helpful [21]. Kaplan–Meier estimates of recurrence-free survival (RFS) at 3 years were 0% for the ctDNA-positive and 90% for the ctDNA-negative groups (Figure 2A). These studies showed that ctDNA could be used to monitor MRD in early stage CRC patients.

Figure 2. Kaplan–Meier estimates of recurrence-free interval according to ctDNA status in patients with stage II and III colon cancer after surgery (postoperative). In (A) Recurrence-free survival (RFS) in colorectal stage II patients post-surgery not treated with adjuvant chemotherapy. Patients with ctDNA-positive status postoperative had a markedly reduced RFS compared with those with a ctDNA-negative status. From Tie et al. [21]; (B) Kaplan–Meier estimates of recurrence-free interval according to ctDNA status in patients with stage III colon cancer after surgery. From Tie et al. [57].

Tie et al. [57] also studied ctDNA in stage III colon cancer patients. In this study, ctDNA was detectable in 20 out of 96 (21%) patients postoperatively (4–10 weeks after surgery), and the recurrence-free survival (RFS) at 3 years in this group was 47% (95% CI, 24–68%) compared to 76% in those with undetectable postoperative ctDNA (95% CI, 61–86%) (Figure 2B) [57]. Patients with detectable ctDNA after surgery had an increased risk of recurrence (HR, 3.8; 95% CI, 2.4–21.0; p < 0.001) (Figure 2B). Like stage II patients, postoperative ctDNA status remained independently associated with recurrence-free interval (RFI) after adjusting for known clinicopathologic risk factors (HR, 7.5; 95% CI, 3.5–16.1; p < 0.001) [57]. In conclusion, in patients with stage II and III colon cancer, ctDNA may be a useful prognostic marker after surgery and could guide initial adjuvant treatment. In locally advanced rectal cancer, postoperative ctDNA detection was also predictive of recurrence [59].

Tie et al. [60], using a meta-analysis approach from their three studies [21][57][59], showed that patients with non-metastatic CRC with detectable ctDNA after surgery had poorer 5-year recurrence-free (38.6% vs. 85.5%; p < 0.001) and overall survival (64.6% vs. 89.4%; p < 0.001). Analysis of ctDNA 4 to 10 weeks after surgery is a powerful prognostic marker [60]. In a study by Reinert et al. [61], conducted in a cohort of 125 CRC patients (stages I to III), ctDNA was quantified in the preoperative and postoperative plasma samples. The study showed that the patients with detectable ctDNA at postoperative day 30 were seven times (HR, 7.2; 95% CI, 2.7–19.0; p ≤ 0.001) more likely to have cancer recurrence compared to those with undetectable ctDNA [61]. ctDNA status was the only significant prognostic factor associated with recurrence-free survival (RFS) [61]. Other studies in CRC showed similar results [23]. In conclusion, ctDNA could be used to monitor MRD in early stage CRC patients postoperative. In other early stage cancers, such as breast [62] and pancreatic cancer [63], it was also shown that ctDNA detection after curative surgery (postoperative) was predictive of early cancer relapse. Therefore, ctDNA is a robust predictor of disease recurrence, as shown by the studies in CRC and other types of cancers.

4. Role of ctDNA in Assessing the Efficacy of Adjuvant Therapy in Colorectal Cancer

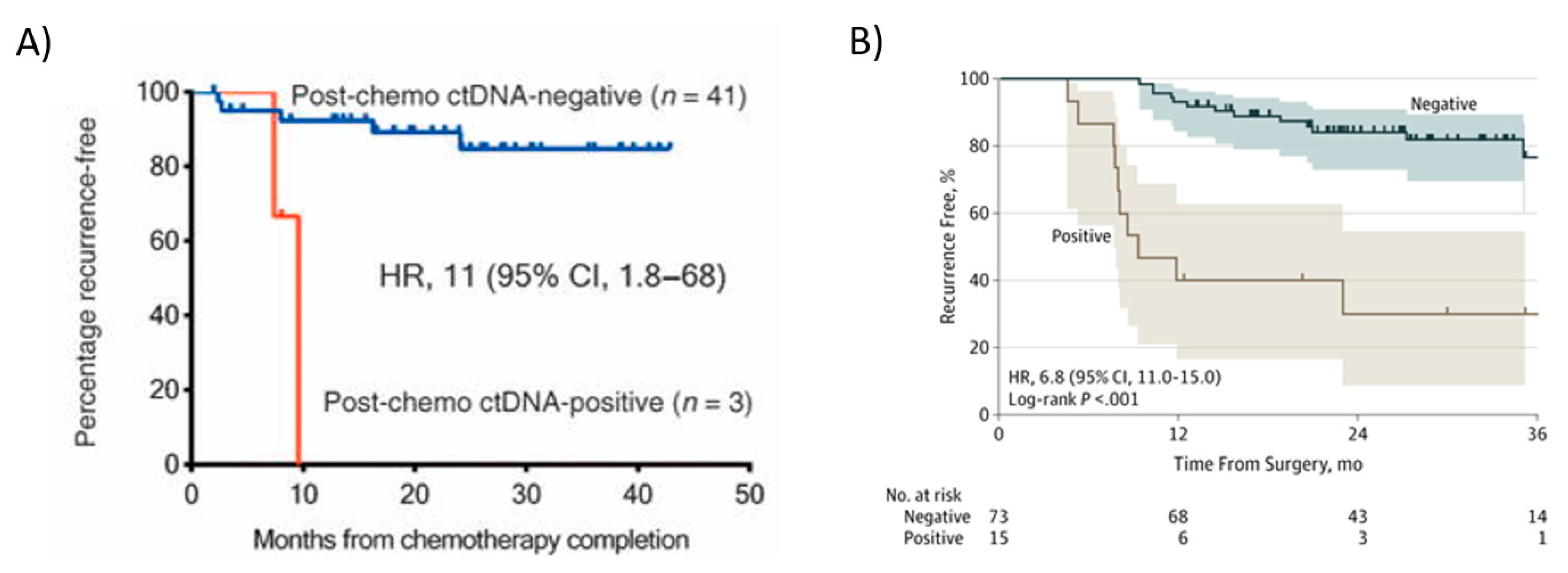

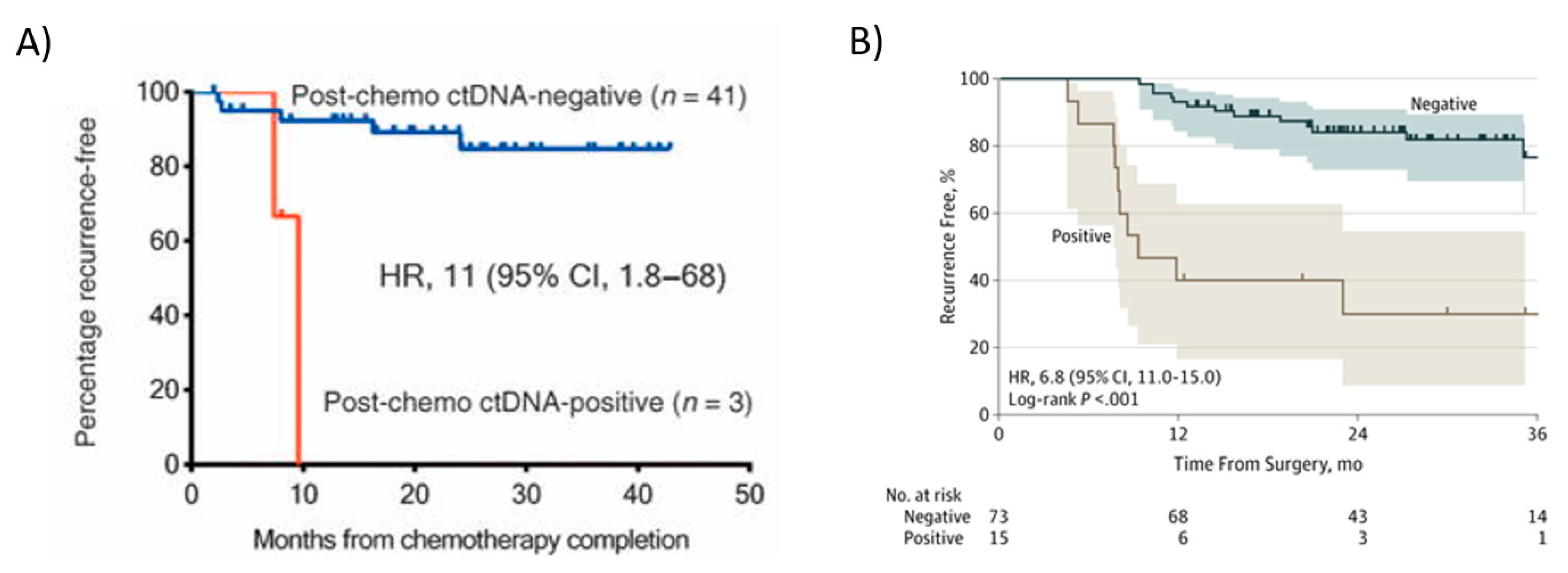

Tie et al. also demonstrated in stage II colon cancer patients that being ctDNA-positive at the completion of adjuvant chemotherapy treatment predicted a very high risk of radiologic recurrence [21]. ctDNA detection immediately after completion of chemotherapy was associated with poorer RFS (HR,11; 95% CI, 1.8 to 68; p ≤ 0.001) (Figure 3A). In this study, all patients had recurrence if ctDNA was detectable after chemotherapy. The median lead time from ctDNA detection to radiologic recurrence was over 5 months, which might be sufficient to change patient management. Personalized serial measurements of ctDNA during adjuvant therapy could be a real-time marker of adjuvant therapy impact. In stage III patients, Tie et al. [57] reported that the ctDNA status of the post-chemotherapy sample was strongly associated with recurrence-free interval (RFI) (HR, 6.8; 95% CI, 11.0–157.0; p < 0.001) [57]. The three-year recurrence-free survival (RFS) was 30% (95% CI, 9–55%) for cases with detectable ctDNA and 77% (95% CI, 60–87%) for those with undetectable ctDNA after chemotherapy (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Kaplan–Meier estimates of recurrence-free interval according to ctDNA in colon cancer patients after adjuvant chemotherapy. ctDNA status after adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with colon cancer. (A) Stage II; ctDNA positivity immediately after completion patieof chemotherapy was associated with poorer RFS. From Tie et al., 2016 [21]. (B) In Stage III. From Tie et al. [57].

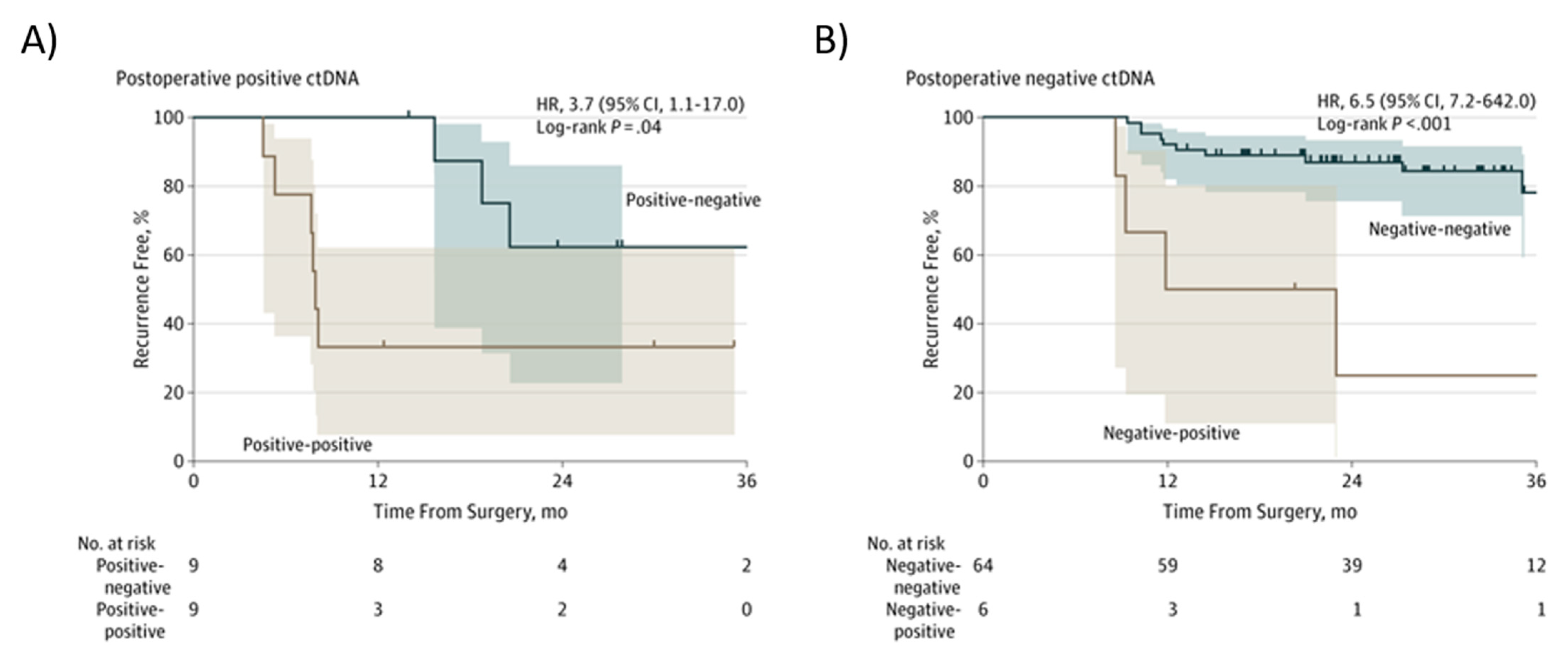

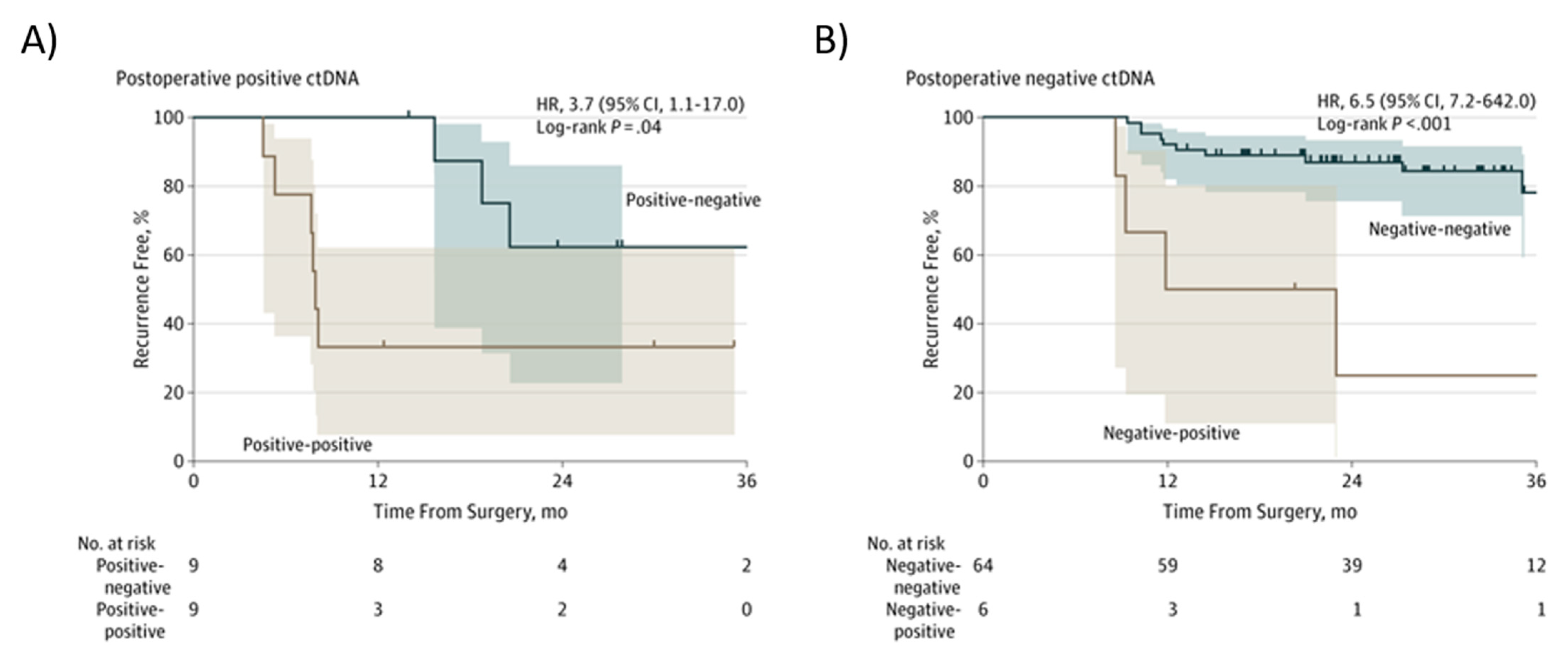

In patients with stage III CRC, a positive postsurgical ctDNA finding and a positive ctDNA finding after chemotherapy (“Positive-positive”; Figure 4A), an inferior RFI was seen compared to patients in whom ctDNA became undetectable after chemotherapy (Positive-negative, Figure 4A) (HR, 3.7; 95% CI, 1.1–17.0; p = 0.04) [57]. In patients with a negative postsurgical ctDNA finding and a negative ctDNA results after chemotherapy (“Negative-negative”; Figure 4B), there was a superior RFI compared to patients in whom ctDNA became detectable after chemotherapy (Negative-positive; Figure 4B) (HR, 6,5; 95% CI, 7.2–642.0, p < 0.001) [57].

Figure 4. Kaplan–Meier estimates of recurrence-free interval according to ctDNA in stage III colon another cancer patients after chemotherapy. (A) Postoperative positive ctDNA; (B) Postoperative negative ctDNA. From Tie et al. [57].

In another study, Reinert et al. [61] reported a 17 times higher risk of recurrence in patients with CRC if ctDNA was detectable after completion of chemotherapy (HR, 17.5; 95% CI, 5.4–56.5; p < 0.001) [61]. In this study, 3 out of 10 patients (30%) with detectable postoperative ctDNA cleared ctDNA after chemotherapy and were disease-free long term, and the other 7 patients with detectable ctDNA after chemotherapy had disease relapse [61]. During surveillance after definitive therapy, ctDNA-positive patients were more than 40 times more likely to experience disease recurrence than ctDNA-negative patients (HR, 43.5; 95% CI, 9.8–193.5; p < 0.001) [61]. Serial ctDNA analyses revealed disease recurrence up to 16.6 months ahead of standard-of-care radiologic imaging (mean, 8.7 months; range, 0.8–16.5 months) [61].

Tarazona et al. [23] studied colon cancer patients and reported an 85.7% recurrence in patients with detectable ctDNA post-chemotherapy (HR 10.02; 95% CI 9.202–307.3; p < 0.0001). In this study, one out of seven patients cleared ctDNA after chemotherapy and remained disease-free in the long term [23]. Genetic variants were studied in tumor tissue using a custom-targeted NGS panel, and two variants with the highest VAF in each patient were selected to track ctDNA in the plasma samples by ddPCR [23]. The detection of ctDNA post-operative at follow-up after adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with localized colon cancer preceded radiological recurrence with a median lead time of 11.5 months [23].

All these studies provide evidence supporting the utility of ctDNA to inform clinicians on the efficacy of adjuvant therapy and suggest that clearance of ctDNA after chemotherapy could be considered a surrogate marker of survival and adjuvant therapy effectiveness. ctDNA may be used as a real-time marker of adjuvant therapy effectiveness, opening new strategies for enrolling high-risk patients with detectable ctDNA in different therapies. Owing to the high specificity of ctDNA for the prediction of disease recurrence, patients with detectable ctDNA might be considered candidates for the escalation of adjuvant therapy over the standard-of-care approach to reduce the risk of disease recurrence [43]. Conversely, patients who lack detectable ctDNA, as determined using a sufficiently sensitive assay, and who have a low risk of disease recurrence might benefit from de-escalation to less-intense adjuvant therapies that reduce the risk of toxicities [43]. ctDNA analysis can potentially change the postoperative management of CRC by enabling risk stratification, chemotherapy monitoring, and early relapse detection.

5. Potential Role of ctDNA in Surveillance for Colorectal Cancer Patients

Regardless of whether patients received adjuvant therapy, the early detection of recurrence during follow-up is associated with improved survival in patients with early stage CRC [42]. However, the biomarker now used as the standard of care for CEA has limited sensitivity and specificity [39][40][41]. CT scans improve the detection of recurrence but are associated with radiation exposure, high cost, inter-reader variability, and a high rate of false positivity [64]. Additionally, by the time CT detection occurs, it may be too late for surgical management. Several studies suggested that ctDNA can diagnose CRC recurrence much earlier than standard surveillance methods [59][61][65][66]. In these studies, detectable ctDNA during surveillance was associated with cancer relapse, and ctDNA detection preceded radiologic relapse by a median time interval from 3 to 11.5 months.6. ctDNA in Monitoring Response to Treatment in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer

Radiographic imaging and serum CEA levels are currently used to monitor disease status in metastatic CRC (mCRC) patients. However, serum CEA levels might only be elevated in 70–80% of patients [40][67]. Several studies employed ctDNA as a biomarker of metastatic disease to monitor disease response to systemic therapy and to assess the overall disease burden. Early changes in ctDNA during treatment with standard therapies are shown to predict radiological responses in patients with mCRC [68][69][70]. A decrease in the ctDNA level during systemic therapy in mCRC correlates with tumor response [11][68][70][71][72]. Garlan et al. [70] showed in a study of mCRC patients that reductions in ctDNA concentration of ≥80% after first-line or second-line chemotherapy were associated with a significantly improved objective response rate (47.1% versus 0%; p = 0.003) and longer median PFS (8.5 months versus 2.4 months; HR 0.19, 95% CI 0.09–0.40; p < 0.0001) and OS (27.1 months versus 11.2 months; HR 0.25, 95% CI 0.11–0.57; p < 0.001) [70]. These authors studied changes in ctDNA, before and after chemotherapy, by the identification of somatic alterations or the hypermethylation of two genes (WIF1 and NPY) and concluded that early change (after cycle one or cycle two) in ctDNA level was a marker of therapeutic efficacy [70]. Tie et al. evaluated 53 mCRC (treatment naïve) patients receiving standard first-line chemotherapy by monitoring ctDNA levels [68]. Tumors were sequenced using a panel of 15 genes frequently mutated in mCRC to identify candidate mutations for ctDNA analysis. For each patient, one tumor mutation was selected to assess the presence and the level of ctDNA in plasma samples using Safe-SeqS. Results indicated that patients with a reduction in ctDNA just before cycle two also had a radiological-confirmed response 8–10 weeks later [68]. Significant reductions in ctDNA (median 5.7-fold; p < 0.001) levels were observed before cycle two, which correlated with CT responses at 8–10 weeks (odds ratio = 5.25 with a 10-fold ctDNA reduction; p = 0.016). Overall, 14/19 (74%) patients who had a ≥10-fold reduction in ctDNA levels had a radiologic response measure at 8–10 weeks, while only 8/23 (35%) patients with lesser reduction in ctDNA levels responded [odds ratio = 5.25; 95% CI 1.38–19.93; p = 0.016]. Major reductions (>10-fold) versus lesser reduction in ctDNA pre-cycle two were associated with a trend for increased PFS (median 14.7 versus 8.1 months; HR = 1.87; p = 0.266). The optimal criterion for predicting response to therapy was ≥10-fold change in ctDNA after cycle one of chemotherapy. Patients who met this criterion experienced a trend of longer PFS than patients with <10-fold drop in ctDNA (median PFS, 14.7 versus 8.1 months; HR = 1.87; 95% CI 0.62–5.61). In metastatic CRC, data suggest that ctDNA changes can occur rapidly in response to systemic therapy, with ctDNA variations at 2 weeks being predictive of subsequent radiographic results in restaging studies at 2 months [68]. In conclusion, early changes in ctDNA in treatment naïve mCRC patients during first-line chemotherapy predict the later radiologic response [68]. No significant relationship was found between fold change and OS [68]. ctDNA might be incorporated as a biomarker to assess mCRC patient response to treatment. If a patient’s non-response to each treatment could be reliably assessed earlier, such as with serial ctDNA analysis, an earlier switch to an alternative therapy may be of benefit, minimizing the side-effects of the ineffective therapy and providing the opportunity for a more effective one [68]. Another important impact of serial ctDNA measurements would be in patients with the non-measurable disease by RECIST criteria, where a reliable measure of ctDNA response would assist clinical decision making [68].References

- Corcoran, R.B.; Chabner, B.A. Application of Cell-free DNA Analysis to Cancer Treatment. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 1754–1765.

- Snyder, M.W.; Kircher, M.; Hill, A.J.; Daza, R.M.; Shendure, J. Cell-free DNA Comprises an In Vivo Nucleosome Footprint that Informs Its Tissues-of-Origin. Cell 2016, 164, 57–68.

- Schwarzenbach, H.; Hoon, D.S.; Pantel, K. Cell-free nucleic acids as biomarkers in cancer patients. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2011, 11, 426–437.

- Kalluri, R.; LeBleu, V.S. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science 2020, 367, eaau6977.

- Yao, W.; Mei, C.; Nan, X.; Hui, L. Evaluation and comparison of in vitro degradation kinetics of DNA in serum, urine and saliva: A qualitative study. Gene 2016, 590, 142–148.

- Vietsch, E.E.; Graham, G.T.; McCutcheon, J.N.; Javaid, A.; Giaccone, G.; Marshall, J.L.; Wellstein, A. Reprint of: Circulating cell-free DNA mutation patterns in early and late stage colon and pancreatic cancer. Cancer Genet. 2018, 228–229, 131–142.

- Tamkovich, S.N.; Cherepanova, A.V.; Kolesnikova, E.V.; Rykova, E.Y.; Pyshnyi, D.V.; Vlassov, V.V.; Laktionov, P.P. Circulating DNA and DNase activity in human blood. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1075, 191–196.

- Botezatu, I.; Serdyuk, O.; Potapova, G.; Shelepov, V.; Alechina, R.; Molyaka, Y.; Ananev, V.; Bazin, I.; Garin, A.; Narimanov, M.; et al. Genetic analysis of DNA excreted in urine: A new approach for detecting specific genomic DNA sequences from cells dying in an organism. Clin. Chem. 2000, 46, 1078–1084.

- Siravegna, G.; Geuna, E.; Mussolin, B.; Crisafulli, G.; Bartolini, A.; Galizia, D.; Casorzo, L.; Sarotto, I.; Scaltriti, M.; Sapino, A.; et al. Genotyping tumour DNA in cerebrospinal fluid and plasma of a HER2-positive breast cancer patient with brain metastases. ESMO Open 2017, 2, e000253.

- Seoane, J.; De Mattos-Arruda, L.; Le Rhun, E.; Bardelli, A.; Weller, M. Cerebrospinal fluid cell-free tumour DNA as a liquid biopsy for primary brain tumours and central nervous system metastases. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 211–218.

- Diehl, F.; Schmidt, K.; Choti, M.A.; Romans, K.; Goodman, S.; Li, M.; Thornton, K.; Agrawal, N.; Sokoll, L.; Szabo, S.A.; et al. Circulating mutant DNA to assess tumor dynamics. Nat. Med. 2008, 14, 985–990.

- Lee, J.S.; Kim, M.; Seong, M.W.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, Y.K.; Kang, H.J. Plasma vs. serum in circulating tumor DNA measurement: Characterization by DNA fragment sizing and digital droplet polymerase chain reaction. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2020, 58, 527–532.

- Underhill, H.R.; Kitzman, J.O.; Hellwig, S.; Welker, N.C.; Daza, R.; Baker, D.N.; Gligorich, K.M.; Rostomily, R.C.; Bronner, M.P.; Shendure, J. Fragment Length of Circulating Tumor DNA. PLoS Genet. 2016, 12, e1006162.

- Mouliere, F.; Robert, B.; Arnau Peyrotte, E.; Del Rio, M.; Ychou, M.; Molina, F.; Gongora, C.; Thierry, A.R. High fragmentation characterizes tumour-derived circulating DNA. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23418.

- Zheng, Y.W.; Chan, K.C.; Sun, H.; Jiang, P.; Su, X.; Chen, E.Z.; Lun, F.M.; Hung, E.C.; Lee, V.; Wong, J.; et al. Nonhematopoietically derived DNA is shorter than hematopoietically derived DNA in plasma: A transplantation model. Clin. Chem. 2012, 58, 549–558.

- Mouliere, F.; Chandrananda, D.; Piskorz, A.M.; Moore, E.K.; Morris, J.; Ahlborn, L.B.; Mair, R.; Goranova, T.; Marass, F.; Heider, K.; et al. Enhanced detection of circulating tumor DNA by fragment size analysis. Sci. Transl. Med. 2018, 10, eaat4921.

- Volik, S.; Alcaide, M.; Morin, R.D.; Collins, C. Cell-free DNA (cfDNA): Clinical Significance and Utility in Cancer Shaped By Emerging Technologies. Mol. Cancer Res. 2016, 14, 898–908.

- Frattini, M.; Gallino, G.; Signoroni, S.; Balestra, D.; Battaglia, L.; Sozzi, G.; Leo, E.; Pilotti, S.; Pierotti, M.A. Quantitative analysis of plasma DNA in colorectal cancer patients: A novel prognostic tool. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1075, 185–190.

- Sozzi, G.; Conte, D.; Mariani, L.; Lo Vullo, S.; Roz, L.; Lombardo, C.; Pierotti, M.A.; Tavecchio, L. Analysis of circulating tumor DNA in plasma at diagnosis and during follow-up of lung cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 4675–4678.

- Bettegowda, C.; Sausen, M.; Leary, R.J.; Kinde, I.; Wang, Y.; Agrawal, N.; Bartlett, B.R.; Wang, H.; Luber, B.; Alani, R.M.; et al. Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human malignancies. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 224ra224.

- Tie, J.; Wang, Y.; Tomasetti, C.; Li, L.; Springer, S.; Kinde, I.; Silliman, N.; Tacey, M.; Wong, H.L.; Christie, M.; et al. Circulating tumor DNA analysis detects minimal residual disease and predicts recurrence in patients with stage II colon cancer. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, 8, 346ra392.

- Chaudhuri, A.A.; Chabon, J.J.; Lovejoy, A.F.; Newman, A.M.; Stehr, H.; Azad, T.D.; Khodadoust, M.S.; Esfahani, M.S.; Liu, C.L.; Zhou, L.; et al. Early Detection of Molecular Residual Disease in Localized Lung Cancer by Circulating Tumor DNA Profiling. Cancer Discov. 2017, 7, 1394–1403.

- Tarazona, N.; Gimeno-Valiente, F.; Gambardella, V.; Zuniga, S.; Rentero-Garrido, P.; Huerta, M.; Rosello, S.; Martinez-Ciarpaglini, C.; Carbonell-Asins, J.A.; Carrasco, F.; et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing of circulating-tumor DNA for tracking minimal residual disease in localized colon cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 1804–1812.

- Jahr, S.; Hentze, H.; Englisch, S.; Hardt, D.; Fackelmayer, F.O.; Hesch, R.D.; Knippers, R. DNA fragments in the blood plasma of cancer patients: Quantitations and evidence for their origin from apoptotic and necrotic cells. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 1659–1665.

- Wan, J.C.M.; Massie, C.; Garcia-Corbacho, J.; Mouliere, F.; Brenton, J.D.; Caldas, C.; Pacey, S.; Baird, R.; Rosenfeld, N. Liquid biopsies come of age: Towards implementation of circulating tumour DNA. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 223–238.

- Heitzer, E.; Haque, I.S.; Roberts, C.E.S.; Speicher, M.R. Current and future perspectives of liquid biopsies in genomics-driven oncology. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 71–88.

- Siravegna, G.; Mussolin, B.; Venesio, T.; Marsoni, S.; Seoane, J.; Dive, C.; Papadopoulos, N.; Kopetz, S.; Corcoran, R.B.; Siu, L.L.; et al. How liquid biopsies can change clinical practice in oncology. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 1580–1590.

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249.

- Viale, P.H. The American Cancer Society’s Facts & Figures: 2020 Edition. J. Adv. Pract. Oncol. 2020, 11, 135–136.

- Labianca, R.; Nordlinger, B.; Beretta, G.D.; Mosconi, S.; Mandala, M.; Cervantes, A.; Arnold, D.; Group, E.G.W. Early colon cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2013, 24 (Suppl. 6), vi64–vi72.

- Glynne-Jones, R.; Wyrwicz, L.; Tiret, E.; Brown, G.; Rodel, C.; Cervantes, A.; Arnold, D.; Committee, E.G. Rectal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, iv263.

- Osterman, E.; Glimelius, B. Recurrence Risk After Up-to-Date Colon Cancer Staging, Surgery, and Pathology: Analysis of the Entire Swedish Population. Dis. Colon. Rectum 2018, 61, 1016–1025.

- Babaei, M.; Balavarca, Y.; Jansen, L.; Lemmens, V.; van Erning, F.N.; van Eycken, L.; Vaes, E.; Sjovall, A.; Glimelius, B.; Ulrich, C.M.; et al. Administration of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II-III colon cancer patients: An European population-based study. Int. J. Cancer 2018, 142, 1480–1489.

- Pahlman, L.A.; Hohenberger, W.M.; Matzel, K.; Sugihara, K.; Quirke, P.; Glimelius, B. Should the Benefit of Adjuvant Chemotherapy in Colon Cancer Be Re-Evaluated? J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 1297–1299.

- Bockelman, C.; Engelmann, B.E.; Kaprio, T.; Hansen, T.F.; Glimelius, B. Risk of recurrence in patients with colon cancer stage II and III: A systematic review and meta-analysis of recent literature. Acta Oncol. 2015, 54, 5–16.

- Snyder, R.A.; Hu, C.Y.; Cuddy, A.; Francescatti, A.B.; Schumacher, J.R.; Van Loon, K.; You, Y.N.; Kozower, B.D.; Greenberg, C.C.; Schrag, D.; et al. Association between Intensity of Posttreatment Surveillance Testing and Detection of Recurrence in Patients with Colorectal Cancer. JAMA 2018, 319, 2104–2115.

- Castells, A. Postoperative surveillance in nonmetastatic colorectal cancer patients: Yes, but. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 615–617.

- Sharma, M.R.; Maitland, M.L.; Ratain, M.J. RECIST: No longer the sharpest tool in the oncology clinical trials toolbox---point. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 5145–5149, discussion 5150.

- Bast, R.C., Jr.; Ravdin, P.; Hayes, D.F.; Bates, S.; Fritsche, H., Jr.; Jessup, J.M.; Kemeny, N.; Locker, G.Y.; Mennel, R.G.; Somerfield, M.R.; et al. 2000 update of recommendations for the use of tumor markers in breast and colorectal cancer: Clinical practice guidelines of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J. Clin. Oncol. 2001, 19, 1865–1878.

- Goldstein, M.J.; Mitchell, E.P. Carcinoembryonic antigen in the staging and follow-up of patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer Investig. 2005, 23, 338–351.

- Sorbye, H.; Dahl, O. Carcinoembryonic antigen surge in metastatic colorectal cancer patients responding to oxaliplatin combination chemotherapy: Implications for tumor marker monitoring and guidelines. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 21, 4466–4467.

- Pita-Fernandez, S.; Alhayek-Ai, M.; Gonzalez-Martin, C.; Lopez-Calvino, B.; Seoane-Pillado, T.; Pertega-Diaz, S. Intensive follow-up strategies improve outcomes in nonmetastatic colorectal cancer patients after curative surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 644–656.

- Dasari, A.; Morris, V.K.; Allegra, C.J.; Atreya, C.; Benson, A.B., 3rd; Boland, P.; Chung, K.; Copur, M.S.; Corcoran, R.B.; Deming, D.A.; et al. ctDNA applications and integration in colorectal cancer: An NCI Colon and Rectal-Anal Task Forces whitepaper. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 17, 757–770.

- Cancer Genome Atlas, N. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature 2012, 487, 330–337.

- Strickler, J.H.; Loree, J.M.; Ahronian, L.G.; Parikh, A.R.; Niedzwiecki, D.; Pereira, A.A.L.; McKinney, M.; Korn, W.M.; Atreya, C.E.; Banks, K.C.; et al. Genomic Landscape of Cell-Free DNA in Patients with Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 164–173.

- Forbes, S.A.; Bindal, N.; Bamford, S.; Cole, C.; Kok, C.Y.; Beare, D.; Jia, M.; Shepherd, R.; Leung, K.; Menzies, A.; et al. COSMIC: Mining complete cancer genomes in the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, D945–D950.

- Lecomte, T.; Berger, A.; Zinzindohoue, F.; Micard, S.; Landi, B.; Blons, H.; Beaune, P.; Cugnenc, P.H.; Laurent-Puig, P. Detection of free-circulating tumor-associated DNA in plasma of colorectal cancer patients and its association with prognosis. Int. J. Cancer 2002, 100, 542–548.

- Lehmann-Werman, R.; Neiman, D.; Zemmour, H.; Moss, J.; Magenheim, J.; Vaknin-Dembinsky, A.; Rubertsson, S.; Nellgard, B.; Blennow, K.; Zetterberg, H.; et al. Identification of tissue-specific cell death using methylation patterns of circulating DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E1826–E1834.

- Wallner, M.; Herbst, A.; Behrens, A.; Crispin, A.; Stieber, P.; Goke, B.; Lamerz, R.; Kolligs, F.T. Methylation of serum DNA is an independent prognostic marker in colorectal cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 12, 7347–7352.

- Philipp, A.B.; Stieber, P.; Nagel, D.; Neumann, J.; Spelsberg, F.; Jung, A.; Lamerz, R.; Herbst, A.; Kolligs, F.T. Prognostic role of methylated free circulating DNA in colorectal cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2012, 131, 2308–2319.

- Lee, H.S.; Hwang, S.M.; Kim, T.S.; Kim, D.W.; Park, D.J.; Kang, S.B.; Kim, H.H.; Park, K.U. Circulating methylated septin 9 nucleic Acid in the plasma of patients with gastrointestinal cancer in the stomach and colon. Transl. Oncol. 2013, 6, 290–296.

- Herbst, A.; Vdovin, N.; Gacesa, S.; Ofner, A.; Philipp, A.; Nagel, D.; Holdt, L.M.; Op den Winkel, M.; Heinemann, V.; Stieber, P.; et al. Methylated free-circulating HPP1 DNA is an early response marker in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 140, 2134–2144.

- Herbst, A.; Rahmig, K.; Stieber, P.; Philipp, A.; Jung, A.; Ofner, A.; Crispin, A.; Neumann, J.; Lamerz, R.; Kolligs, F.T. Methylation of NEUROG1 in serum is a sensitive marker for the detection of early colorectal cancer. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 106, 1110–1118.

- Lin, K.Y.; Hung, C.C. Clinical relevance of cross-reactivity between darunavir and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in HIV-infected patients. AIDS 2015, 29, 2213–2214.

- O’Connor, E.S.; Greenblatt, D.Y.; LoConte, N.K.; Gangnon, R.E.; Liou, J.I.; Heise, C.P.; Smith, M.A. Adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II colon cancer with poor prognostic features. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 3381–3388.

- Wirtzfeld, D.A.; Mikula, L.; Gryfe, R.; Ravani, P.; Dicks, E.L.; Parfrey, P.; Gallinger, S.; Pollett, W.G. Concordance with clinical practice guidelines for adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with stage I–III colon cancer: Experience in 2 Canadian provinces. Can. J. Surg. 2009, 52, 92–97.

- Tie, J.; Cohen, J.D.; Wang, Y.; Christie, M.; Simons, K.; Lee, M.; Wong, R.; Kosmider, S.; Ananda, S.; McKendrick, J.; et al. Circulating Tumor DNA Analyses as Markers of Recurrence Risk and Benefit of Adjuvant Therapy for Stage III Colon Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2019, 5, 1710–1717.

- O’Connell, J.B.; Maggard, M.A.; Ko, C.Y. Colon cancer survival rates with the new American Joint Committee on Cancer sixth edition staging. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2004, 96, 1420–1425.

- Tie, J.; Cohen, J.D.; Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Christie, M.; Simons, K.; Elsaleh, H.; Kosmider, S.; Wong, R.; Yip, D.; et al. Serial circulating tumour DNA analysis during multimodality treatment of locally advanced rectal cancer: A prospective biomarker study. Gut 2019, 68, 663–671.

- Tie, J.; Cohen, J.D.; Lo, S.N.; Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Christie, M.; Lee, M.; Wong, R.; Kosmider, S.; Skinner, I.; et al. Prognostic significance of postsurgery circulating tumor DNA in nonmetastatic colorectal cancer: Individual patient pooled analysis of three cohort studies. Int. J. Cancer 2021, 148, 1014–1026.

- Reinert, T.; Henriksen, T.V.; Christensen, E.; Sharma, S.; Salari, R.; Sethi, H.; Knudsen, M.; Nordentoft, I.; Wu, H.T.; Tin, A.S.; et al. Analysis of Plasma Cell-Free DNA by Ultradeep Sequencing in Patients with Stages I to III Colorectal Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2019, 5, 1124–1131.

- Garcia-Murillas, I.; Schiavon, G.; Weigelt, B.; Ng, C.; Hrebien, S.; Cutts, R.J.; Cheang, M.; Osin, P.; Nerurkar, A.; Kozarewa, I.; et al. Mutation tracking in circulating tumor DNA predicts relapse in early breast cancer. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015, 7, 302ra133.

- Sausen, M.; Phallen, J.; Adleff, V.; Jones, S.; Leary, R.J.; Barrett, M.T.; Anagnostou, V.; Parpart-Li, S.; Murphy, D.; Kay Li, Q.; et al. Clinical implications of genomic alterations in the tumour and circulation of pancreatic cancer patients. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7686.

- Chao, M.; Gibbs, P. Caution is required before recommending routine carcinoembryonic antigen and imaging follow-up for patients with early-stage colon cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, e279–e280, author reply e281.

- Scholer, L.V.; Reinert, T.; Orntoft, M.W.; Kassentoft, C.G.; Arnadottir, S.S.; Vang, S.; Nordentoft, I.; Knudsen, M.; Lamy, P.; Andreasen, D.; et al. Clinical Implications of Monitoring Circulating Tumor DNA in Patients with Colorectal Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 5437–5445.

- Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Cohen, J.D.; Kinde, I.; Ptak, J.; Popoli, M.; Schaefer, J.; Silliman, N.; Dobbyn, L.; Tie, J.; et al. Prognostic Potential of Circulating Tumor DNA Measurement in Postoperative Surveillance of Nonmetastatic Colorectal Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2019, 5, 1118–1123.

- Yang, Y.C.; Wang, D.; Jin, L.; Yao, H.W.; Zhang, J.H.; Wang, J.; Zhao, X.M.; Shen, C.Y.; Chen, W.; Wang, X.L.; et al. Circulating tumor DNA detectable in early- and late-stage colorectal cancer patients. Biosci. Rep. 2018, 38, BSR20180322.

- Tie, J.; Kinde, I.; Wang, Y.; Wong, H.L.; Roebert, J.; Christie, M.; Tacey, M.; Wong, R.; Singh, M.; Karapetis, C.S.; et al. Circulating tumor DNA as an early marker of therapeutic response in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 1715–1722.

- Vidal, J.; Muinelo, L.; Dalmases, A.; Jones, F.; Edelstein, D.; Iglesias, M.; Orrillo, M.; Abalo, A.; Rodriguez, C.; Brozos, E.; et al. Plasma ctDNA RAS mutation analysis for the diagnosis and treatment monitoring of metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Ann. Oncol. 2017, 28, 1325–1332.

- Garlan, F.; Laurent-Puig, P.; Sefrioui, D.; Siauve, N.; Didelot, A.; Sarafan-Vasseur, N.; Michel, P.; Perkins, G.; Mulot, C.; Blons, H.; et al. Early Evaluation of Circulating Tumor DNA as Marker of Therapeutic Efficacy in Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Patients (PLACOL Study). Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 5416–5425.

- Berger, A.W.; Schwerdel, D.; Welz, H.; Marienfeld, R.; Schmidt, S.A.; Kleger, A.; Ettrich, T.J.; Seufferlein, T. Treatment monitoring in metastatic colorectal cancer patients by quantification and KRAS genotyping of circulating cell-free DNA. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174308.

- Osumi, H.; Shinozaki, E.; Yamaguchi, K.; Zembutsu, H. Early change in circulating tumor DNA as a potential predictor of response to chemotherapy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 17358.

More