Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 3 by Conner Chen and Version 5 by Conner Chen.

The epidemiology of infections sustained by multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria is rapidly evolving. New drugs are available or are on the horizon. Most are combinations of a β-lactam and a β-lactamase inhibitor. One part is the antibiotic cefiderocol that has a peculiar antibacterial mechanism of action. Dispensing of such an armamentarium requires in-depth knowledge of their microbiological spectrum of activity, pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) properties, and clinical study results. The following will describe the antibacterial strategy of aztreonam in combination with avibactam.

- Aztreonam/Avibactam

- drugs

- pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic

1. Introduction

The epidemiology of infections sustained by multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria is rapidly evolving. New drugs are available or are on the horizon. Most are combinations of a β-lactam and a β-lactamase inhibitor. One part is the antibiotic cefiderocol that has a peculiar antibacterial mechanism of action. Dispensing of such an armamentarium requires in-depth knowledge of their microbiological spectrum of activity, pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) properties, and clinical study results. Here will will describe the aztreonam/avibactam.

2. Aztreonam/Avibactam

Aztreonam is an old antibiotic approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European regulatory authorities in 1986. Its clinical use was strongly limited by the spread of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL) and AmpC-type determinants. Of note, metallo-β-lactamases (MBLs) are able to hydrolyze all β-lactams except for the monobactam aztreonam. However, due to the frequent co-production of class A β-lactamases or AmpC-type determinants within MBL-producing Gram-negatives, aztreonam remains active only in one-third of cases [1]. For this reason, combining aztreonam with avibactam could represent a good antimicrobial strategy. A single product formulation of aztreonam/avibactam is currently under development in phase 3 studies for the treatment of MBL-sustained infections. Aztreonam/avibactam has antimicrobial activity against carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales, P. aeruginosa (including isolates producing Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase, KPC; Verona integron-encoded metallo-β-lactamase, VIM; imipenemase, IMP; New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase, NDM; and oxacillinase, OXA-48), and Stenotrophomonas maltophilia [2][3]. No antimicrobial activity has been reported against A. baumannii (no inhibition of A. baumannii OXA-type enzymes). Resistance in P. aeruginosa has been associated with impermeability (porin loss), the production of AmpC-type (Pseudomonas-derived cephalosporinase 1; PDC) variants, OXA enzymes (other than OXA-48), or hyperexpression of efflux systems, while resistance in Enterobacterales could be associated with a specific amino acid insertion (12 bp duplications) in PBP3 determinants causing a reduction in affinity for aztreonam [2] (Table 1). For antimicrobial susceptibility testing purpose, the concentration of avibactam is fixed at 4 mg/L [4]. No clinical breakpoint (CLSI, EUCAST, or FDA) has been approved for this combination. An EUCAST epidemiological cut-off (ECOFF) value has not been assigned.

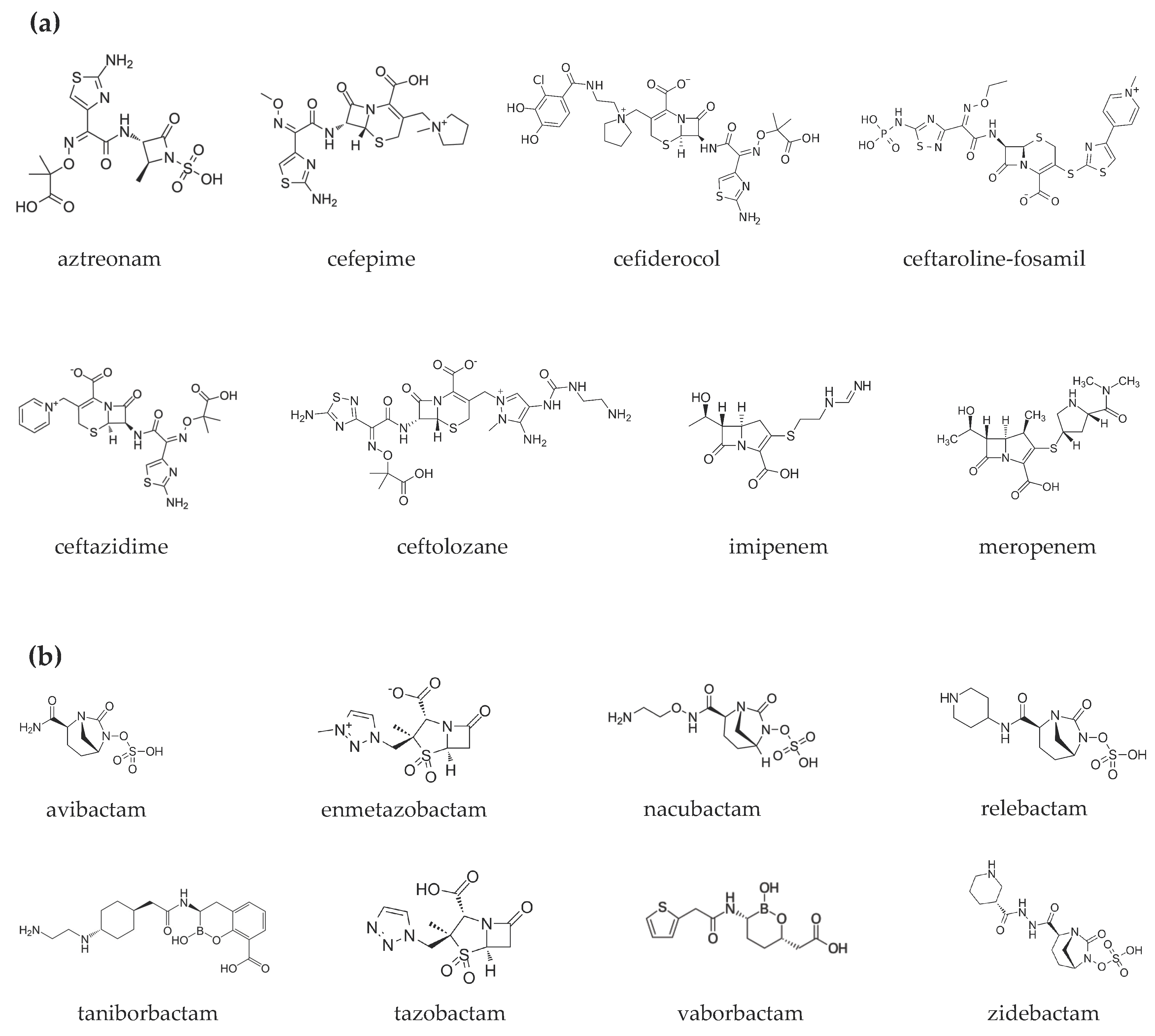

Figure 1. Chemical structures of (a) β-lactams and (b) β-lactamase inhibitors.

Table 1. Microbiological targets.

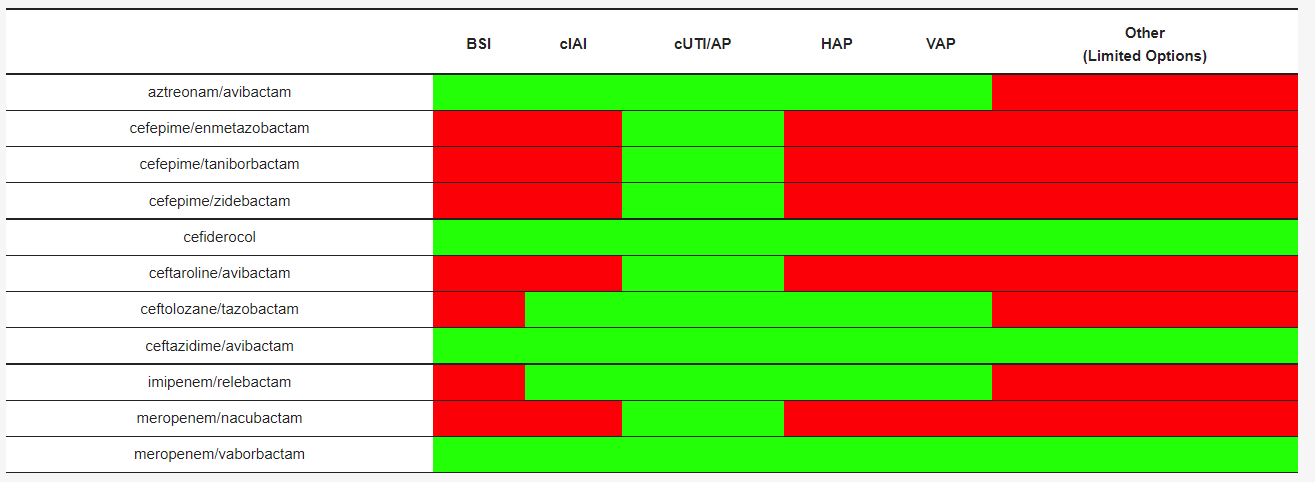

Table 2. Clinical settings investigated or under investigation for each compound.

Table 3. Pharmacokinetic parameters of β-lactams/β-lactamase inhibitors and cefiderocol. The concentrations of β-lactams and β-lactamase inhibitors were determined using liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry.

Abbreviations: CrCl = creatinine clearance, cIAI = complicated intra-abdominal tract infection; cUTI = complicated urinary tract infection; RI = renal insufficiency; FDA = US Food and Drug administration.

| DRUGS | PK/PD Index | T ½ (h) | Vd (L) | Authorized for Use in the EuropeanPB (%) | ELF/ Plasma (%) |

References | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Union and by FDA | References | ||||||||||

| aztreonam/avibactam | 60% fT > MIC/ 50% fT > CT |

2.3–2.8/1.8–2.2 | 20/26 | 56/8 * | 30/30 | [ | |||||

| aztreonam/ avibactam | 6 | ] | [ | 8 | ] | [11 | Not available][12][13] | ||||

| Not available | no | cefepime/ enmetazobactam |

60% fT > MIC/ 20–45% fT > CT |

2.1/** | 18.2/** | 16–19/** | |||||

| cefepime/ | 61/53 | enmetazobactam | Not available | [ | 14 | ][15][ | Not available16] | ||||

| no | cefepime/taniborbactam | 50% fT > MIC/ fAUC24/MIC |

2.1/4.7 * | 18.2/37.4 | |||||||

| cefepime/ taniborbactam |

Not available | Not available | 16–19/** | na | [ | no16 | ][17][18] | ||||

| cefepime/zidebactam | 30% fT > MIC/ fAUC24/MIC |

2.0/1.9 | 15.4/17.4 | 20/< 15 | 39/38 | ||||||

| cefepime/ zidebactam | [ | 19 | ] | [ | 20 | ] | |||||

| Not available | Not available | no | cefiderocol | ƒT/MIC ≥75% | 2.7 | 18 | 40–60 | 10–23 | |||

| cefiderocol | Pneumonia: 2 g q 8 h (7 days) cUTI: 2 g q 8 h (7–14 days) |

CrCl ≥120 mL/min: 2 g q 6 h CrCl 60–120 mL/min: 2 g q 8 h CrCl 30–60 mL/min: 1.5 g q 8 h CrCl 15–30 mL/min: 1 g q 8 h CrCl <15 mL/min: 750 mg q 12 h |

yes | [24][38][39] | [ | 11][21][22] | |||||

| ceftaroline-fosamil/ avibacatm |

40–50% fT > MIC/ f T > CT; fAUC |

2.4/2.0 * | 19.8/18 * | 20/8 * | 23/30 * | [ceftolozane/ | |||||

| ceftaroline-fosamil/ avibactam |

Not available | no | 8 | ] | [23][24] | ||||||

| tazobactam | 35% fT > MIC/ % f T > CT |

3.5/2.5 | 13.5/18.2 | ||||||||

| ceftozolane/ tazobactam |

cIAI: 1.5–3 g q 8 h (4–5 days) Pneumonia: 3 g q 8 h (7 days) Bloodstream infection, skin and soft tissues: 1.5–3 g q 8 h cUTI: 1.5 g q 8 h |

CrCl >50 mL/min: 1.5 g q 8 h 3 g q 8 h CrCl 30–50 mL/min: 750 mg q 8 h 1.5 g q 8 h CrCl 15–29 mL/min: | 21/30 | 61/63 | 375 mg q 8 h 750 mg q 8 h[25][26][27] |

||||||

| yes | [ | 40 | ] | [41][42][43][44] | ceftazidime/avibactam | 50 % fT > MIC/ 40 % fT > CT |

2.0/2.0 | 14.3/15–25 | <10/5.7–8.2 | 52/42 | |

| ceftazidime/ avibactam |

cIAI: 2.5 g q 8 (4–5 days) Pneumonia: 2.5 g q h (7 days) cUTI: 2.5 g q 8 h (5–14 days) |

CrCl >50 mL/min: 2.5 g q 8 h CrCl 31–50 mL/min: 1.25 g q 8 h CrCl 16–30 mL/min: 0.94 g q 12 h CrCl 6–15 mL/min: 0.94 g q 24 h CrCl <5 mL/min: 0.94 g q 48 h | [ | 8 | ] | [11][28][29] | yes[30] | ||||

| [ | 30 | ] | imipenem/relebactam | ||||||||

| imipenem/ relebactam | 6.5% fT > MIC/ fAUC24/MIC |

1/1.2 | cIAI: 1.25 g q 6 h (4–7 days) Pneumonia: 1.25 g q 6 h (7 days) 24.3/19 |

20/22 | 55/54 | cUTI: 1.25 g q 6 h (5–14 days) | CrCl ≥90 mL/min: 1.25 g q 6 h CrCl 60–89 mL/min: 1 g q 6 h CrCl 30–59 mL/min: 0.75 g q 6 h CrCl 15–29 mL/min: 0.5 g q 6 h CrCl <15 mL/min: 0.5 g q 6 h |

yes | [32][45[29][31][32] | ||

| ] | [ | 46 | ] | meropenem/nacubactam | 40% fT > MIC/ fAUC24/MIC * |

1/2.6 * | 15–20/21.9 * | 2/2 * | na | [33] | |

| meropenem/ vaborbactam |

cUTI: 4 g q 8 h (5–14 days) |

CrCl ≥50 mL/min: 4 g q 8 h CrCl 30–49 mL/min: 2 g q 8 h CrCl 15–29 mL/min: 2 g q 12 h CrCl <15 mL/min: 1 g q 12 h |

yes | [37][47][48][49][50] | meropenem/vaborbactam | 40% fT > MIC/ fAUC24/MIC * |

1.3/1.9 | 20.2/18.6 | 2/33 | 65/79 | [ |

| meropenem/nacubactam | 34 | ] | [ | 35 | ] | [36][37] |

Table 4. Recommended dosages and dose adjustment in renal insufficiency.

| Drugs | Recommended Dosage | Adjustment in RI |

|---|---|---|

| Not available | ||

| Not available | ||

| no | ||

References

- Tan, X.; Kim, H.S.; Baugh, K.; Huang, Y.; Kadiyala, N.; Wences, M.; Singh, N.; Wenzler, E.; Bulman, Z.P. Therapeutic Options for Metallo-β-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacterales. Infect. Drug Resist. 2021, 14, 125–142.

- Mauri, C.; Maraolo, A.E.; Di Bella, S.; Luzzaro, F.; Principe, L. The Revival of Aztreonam in Combination with Avibactam against Metallo-β-Lactamase-Producing Gram-Negatives: A Systematic Review of In Vitro Studies and Clinical Cases. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1012.

- Sader, H.S.; Carvalhaes, C.G.; Arends, S.J.R.; Castanheira, M.; Mendes, R.E. Aztreonam/avibactam Activity against Clinical Isolates of Enterobacterales Collected in Europe, Asia and Latin America in 2019. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76, 659–666.

- CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 31st ed.; CLSI Supplement M100; Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute: Malvern, PA, USA, 2021.

- Aztreonam/Avibactam—List Results. ClinicalTrials.gov. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=aztreonam%2Favibactam&term=&cntry=&state=&city=&dist= (accessed on 5 February 2022).

- Cornely, O.A.; Cisneros, J.M.; Torre-Cisneros, J.; Rodríguez-Hernández, M.J.; Tallón-Aguilar, L.; Calbo, E.; Horcajada, J.P.; Queckenberg, C.; Zettelmeyer, U.; Arenz, D.; et al. Pharmacokinetics and Safety of Aztreonam/avibactam for the Treatment of Complicated Intra-Abdominal Infections in Hospitalized Adults: Results from the REJUVENATE Study. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020, 75, 618–627.

- Falcone, M.; Menichetti, F.; Cattaneo, D.; Tiseo, G.; Baldelli, S.; Galfo, V.; Leonildi, A.; Tagliaferri, E.; Di Paolo, A.; Pai, M.P. Pragmatic Options for Dose Optimization of Ceftazidime/avibactam with Aztreonam in Complex Patients. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2021, 76, 1025–1031.

- Dimelow, R.; Wright, J.G.; MacPherson, M.; Newell, P.; Das, S. Population Pharmacokinetic Modelling of Ceftazidime and Avibactam in the Plasma and Epithelial Lining Fluid of Healthy Volunteers. Drugs R&D 2018, 18, 221–230.

- Karaiskos, I.; Lagou, S.; Pontikis, K.; Rapti, V.; Poulakou, G. The “Old” and the “New” Antibiotics for MDR Gram-Negative Pathogens: For Whom, When, and How. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 151.

- Di Paolo, A.; Gori, G.; Tascini, C.; Danesi, R.; Del Tacca, M. Clinical Pharmacokinetics of Antibacterials in Cerebrospinal Fluid. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2013, 52, 511–542.

- Nichols, W.W.; Newell, P.; Critchley, I.A.; Riccobene, T.; Das, S. Avibactam Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Targets. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, 02446-17.

- Luci, G.; Mattioli, F.; Falcone, M.; Di Paolo, A. Pharmacokinetics of Non-β-Lactam β-Lactamase Inhibitors. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 769.

- Ramsey, C.; MacGowan, A.P. A Review of the Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Aztreonam. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016, 71, 2704–2712.

- Bernhard, F.; Odedra, R.; Sordello, S.; Cardin, R.; Franzoni, S.; Charrier, C.; Belley, A.; Warn, P.; Machacek, M.; Knechtle, P. Pharmacokinetics-Pharmacodynamics of Enmetazobactam Combined with Cefepime in a Neutropenic Murine Thigh Infection Model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e00078-20.

- Das, S.; Fitzgerald, R.; Ullah, A.; Bula, M.; Collins, A.M.; Mitsi, E.; Reine, J.; Hill, H.; Rylance, J.; Ferreira, D.M.; et al. Intrapulmonary Pharmacokinetics of Cefepime and Enmetazobactam in Healthy Volunteers: Towards New Treatments for Nosocomial Pneumonia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 65, e01468-20.

- Okamoto, M.P.; Nakahiro, R.K.; Chin, A.; Bedikian, A. Cefepime Clinical Pharmacokinetics. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1993, 25, 88–102.

- Abdelraouf, K.; Almarzoky Abuhussain, S.; Nicolau, D.P. In Vivo Pharmacodynamics of New-Generation β-Lactamase Inhibitor Taniborbactam (formerly VNRX-5133) in Combination with Cefepime against Serine-β-Lactamase-Producing Gram-Negative Bacteria. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020, 75, 3601–3610.

- Dowell, J.A.; Dickerson, D.; Henkel, T. Safety and Pharmacokinetics in Human Volunteers of Taniborbactam (VNRX-5133), a Novel Intravenous β-Lactamase Inhibitor. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65, e0105321.

- Lepak, A.J.; Zhao, M.; Andes, D.R. WCK 5222 (Cefepime/Zidebactam) Pharmacodynamic Target Analysis against Metallo-β-Lactamase Producing in the Neutropenic Mouse Pneumonia Model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e01648-19.

- Rodvold, K.A.; Gotfried, M.H.; Chugh, R.; Gupta, M.; Patel, A.; Chavan, R.; Yeole, R.; Friedland, H.D.; Bhatia, A. Plasma and Intrapulmonary Concentrations of Cefepime and Zidebactam Following Intravenous Administration of WCK 5222 to Healthy Adult Subjects. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e00682-18.

- Saisho, Y.; Katsube, T.; White, S.; Fukase, H.; Shimada, J. Pharmacokinetics, Safety, and Tolerability of Cefiderocol, a Novel Siderophore Cephalosporin for Gram-Negative Bacteria, in Healthy Subjects. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e02163-17.

- Katsube, T.; Echols, R.; Wajima, T. Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Profiles of Cefiderocol, a Novel Siderophore Cephalosporin. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 69, S552–S558.

- Riccobene, T.A.; Su, S.F.; Rank, D. Single- and Multiple-Dose Study to Determine the Safety, Tolerability, and Pharmacokinetics of Ceftaroline Fosamil in Combination with Avibactam in Healthy Subjects. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 1496–1504.

- Riccobene, T.A.; Pushkin, R.; Jandourek, A.; Knebel, W.; Khariton, T. Penetration of Ceftaroline into the Epithelial Lining Fluid of Healthy Adult Subjects. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 5849–5857.

- Lepak, A.J.; Reda, A.; Marchillo, K.; Van Hecker, J.; Craig, W.A.; Andes, D. Impact of MIC Range for Pseudomonas Aeruginosa and Streptococcus Pneumoniae on the Ceftolozane in Vivo Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic Target. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 6311–6314.

- Xiao, A.J.; Caro, L.; Popejoy, M.W.; Huntington, J.A.; Kullar, R. PK/PD Target Attainment with Ceftolozane/Tazobactam Using Monte Carlo Simulation in Patients with Various Degrees of Renal Function, Including Augmented Renal Clearance and End-Stage Renal Disease. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2017, 6, 137–148.

- Nicolau, D.P.; De Waele, J.; Kuti, J.L.; Caro, L.; Larson, K.B.; Yu, B.; Gadzicki, E.; Zeng, Z.; Rhee, E.G.; Rizk, M.L. Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Ceftolozane/Tazobactam in Critically Ill Patients With Augmented Renal Clearance. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2021, 57, 106299.

- Davido, B.; Fellous, L.; Lawrence, C.; Maxime, V.; Rottman, M.; Dinh, A. Ceftazidime-Avibactam and Aztreonam, an Interesting Strategy to Overcome β-Lactam Resistance Conferred by Metallo-β-Lactamases in Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e01008-17.

- Merdjan, H.; Rangaraju, M.; Tarral, A. Safety and Pharmacokinetics of Single and Multiple Ascending Doses of Avibactam Alone and in Combination with Ceftazidime in Healthy Male Volunteers: Results of Two Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Studies. Clin. Drug Investig. 2015, 35, 307–317.

- Van Duin, D.; Bonomo, R.A. Ceftazidime/Avibactam and Ceftolozane/Tazobactam: Second-Generation β-Lactam/β-Lactamase Inhibitor Combinations. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 63, 234–241.

- Rizk, M.L.; Rhee, E.G.; Jumes, P.A.; Gotfried, M.H.; Zhao, T.; Mangin, E.; Bi, S.; Chavez-Eng, C.M.; Zhang, Z.; Butterton, J.R. Intrapulmonary Pharmacokinetics of Relebactam, a Novel β-Lactamase Inhibitor, Dosed in Combination with Imipenem-Cilastatin in Healthy Subjects. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2018, 62, e01411-17.

- Heo, Y.-A. Imipenem/Cilastatin/Relebactam: A Review in Gram-Negative Bacterial Infections. Drugs 2021, 81, 377–388.

- Mallalieu, N.L.; Winter, E.; Fettner, S.; Patel, K.; Zwanziger, E.; Attley, G.; Rodriguez, I.; Kano, A.; Salama, S.M.; Bentley, D.; et al. Safety and Pharmacokinetic Characterization of Nacubactam, a Novel β-Lactamase Inhibitor, Alone and in Combination with Meropenem, in Healthy Volunteers. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e02229-19.

- Dhillon, S. Meropenem/Vaborbactam: A Review in Complicated Urinary Tract Infections. Drugs 2018, 78, 1259–1270.

- Wenzler, E.; Scoble, P.J. An Appraisal of the Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Properties of Meropenem-Vaborbactam. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2020, 9, 769–784.

- Wenzler, E.; Gotfried, M.H.; Loutit, J.S.; Durso, S.; Griffith, D.C.; Dudley, M.N.; Rodvold, K.A. Meropenem-RPX7009 Concentrations in Plasma, Epithelial Lining Fluid, and Alveolar Macrophages of Healthy Adult Subjects. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 7232–7239.

- Zhuang, L.; Yu, Y.; Wei, X.; Florian, J.; Jang, S.H.; Reynolds, K.S.; Wang, Y. Evaluation of Hemodialysis Effect on Pharmacokinetics of Meropenem/Vaborbactam in End-Stage Renal Disease Patients Using Modeling and Simulation. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 60, 1011–1021.

- Bassetti, M.; Echols, R.; Matsunaga, Y.; Ariyasu, M.; Doi, Y.; Ferrer, R.; Lodise, T.P.; Naas, T.; Niki, Y.; Paterson, D.L.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Cefiderocol or Best Available Therapy for the Treatment of Serious Infections Caused by Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria (CREDIBLE-CR): A Randomised, Open-Label, Multicentre, Pathogen-Focused, Descriptive, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 226–240.

- Portsmouth, S.; Van Veenhuyzen, D.; Echols, R.; Machida, M.; Ferreira, J.C.A.; Ariyasu, M.; Tenke, P.; Nagata, T.D. Cefiderocol versus Imipenem-Cilastatin for the Treatment of Complicated Urinary Tract Infections Caused by Gram-Negative Uropathogens: A Phase 2, Randomised, Double-Blind, Non-Inferiority Trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 1319–1328.

- Wagenlehner, F.M.; Umeh, O.; Steenbergen, J.; Yuan, G.; Darouiche, R.O. Ceftolozane-Tazobactam Compared with Levofloxacin in the Treatment of Complicated Urinary-Tract Infections, Including Pyelonephritis: A Randomised, Double-Blind, Phase 3 Trial (ASPECT-cUTI). Lancet 2015, 385, 1949–1956.

- Kollef, M.H.; Nováček, M.; Kivistik, Ü.; Réa-Neto, Á.; Shime, N.; Martin-Loeches, I.; Timsit, J.-F.; Wunderink, R.G.; Bruno, C.J.; Huntington, J.A.; et al. Ceftolozane-Tazobactam versus Meropenem for Treatment of Nosocomial Pneumonia (ASPECT-NP): A Randomised, Controlled, Double-Blind, Phase 3, Non-Inferiority Trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 1299–1311.

- Dietch, Z.C.; Shah, P.M.; Sawyer, R.G. Advances in Intra-Abdominal Sepsis: What Is New? Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2015, 17, 497.

- Hernández-Tejedor, A.; Merino-Vega, C.D.; Martín-Vivas, A.; Ruiz de Luna-González, R.; Delgado-Iribarren, A.; Gabán-Díez, Á.; Temprano-Gómez, I.; De la Calle-Pedrosa, N.; González-Jiménez, A.I.; Algora-Weber, A. Successful Treatment of Multidrug-Resistant Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Breakthrough Bacteremia with Ceftolozane/tazobactam. Infection 2017, 45, 115–117.

- Sousa Dominguez, A.; Perez-Rodríguez, M.T.; Nodar, A.; Martinez-Lamas, L.; Perez-Landeiro, A.; Crespo Casal, M. Successful Treatment of MDR Pseudomonas Aeruginosa Skin and Soft-Tissue Infection with Ceftolozane/tazobactam. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017, 72, 1262–1263.

- Imipenem, Cilastatin Sodium, and Relebactam Monohydrate for the Treatment of Cancer Patients with Febrile Neutropenia. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04983901 (accessed on 5 February 2022).

- Sims, M.; Mariyanovski, V.; McLeroth, P.; Akers, W.; Lee, Y.-C.; Brown, M.L.; Du, J.; Pedley, A.; Kartsonis, N.A.; Paschke, A. Prospective, Randomized, Double-Blind, Phase 2 Dose-Ranging Study Comparing Efficacy and Safety of Imipenem/cilastatin plus Relebactam with Imipenem/cilastatin Alone in Patients with Complicated Urinary Tract Infections. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017, 72, 2616–2626.

- Kaye, K.S.; Bhowmick, T.; Metallidis, S.; Bleasdale, S.C.; Sagan, O.S.; Stus, V.; Vazquez, J.; Zaitsev, V.; Bidair, M.; Chorvat, E.; et al. Effect of Meropenem-Vaborbactam vs Piperacillin-Tazobactam on Clinical Cure or Improvement and Microbial Eradication in Complicated Urinary Tract Infection: The TANGO I Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2018, 319, 788–799.

- Buckman, S.A.; Krekel, T.; Muller, A.E.; Mazuski, J.E. Ceftazidime-Avibactam for the Treatment of Complicated Intra-Abdominal Infections. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2016, 17, 2341–2349.

- Torres, A.; Zhong, N.; Pachl, J.; Timsit, J.-F.; Kollef, M.; Chen, Z.; Song, J.; Taylor, D.; Laud, P.J.; Stone, G.G.; et al. Ceftazidime-Avibactam versus Meropenem in Nosocomial Pneumonia, Including Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia (REPROVE): A Randomised, Double-Blind, Phase 3 Non-Inferiority Trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 285–295.

- Wagenlehner, F.M.; Sobel, J.D.; Newell, P.; Armstrong, J.; Huang, X.; Stone, G.G.; Yates, K.; Gasink, L.B. Ceftazidime-Avibactam Versus Doripenem for the Treatment of Complicated Urinary Tract Infections, Including Acute Pyelonephritis: RECAPTURE, a Phase 3 Randomized Trial Program. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 63, 754–762.

More